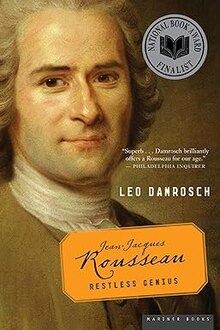

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius is a 2005 biography by Leo Damrosch, published by Houghton Mifflin. The book depicts the life of eighteenth-century philosopher, writer, composer, and political theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau, documenting his unorthodox rise from obscure beginnings to show how the orphaned and unschooled Rousseau rose from meandering journeyman to become one of the foremost thinkers in the Age of Enlightenment.

| |

| Author | Leo Damrosch |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin[1] |

Publication date | 2005 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 566 |

| ISBN | 0618872027 |

The book was a finalist for the 2005 National Book Award for Nonfiction.[2]

Narrative

editThe biography details Rousseau's life, explaining his tumultuous beginnings when his mother died shortly after he was born and his father abandoned him during his adolescence. Rousseau spent the next years travelling around Europe and developed a relationship with Madame de Warens. With no formal education and penniless, he worked various jobs such as a valet, a diplomatic secretary, a teacher, and a translator for a monk. Around the age of 35, Rousseau settled in Paris and began his writings for which he is known. He wrote the opera Le Devin du Village (The Village Soothsayer) in 1752, which is still performed to this day. In Paris, he married Therese Levasseur.

Rousseau's ideas about the inherent goodness of people and societal institutions' inhibition of that goodness with its social stratification and regulations proved divisive in their day. This view contrasted with the prevailing Enlightenment view that people were inherently immoral and that institutions, such as government or the church, were required to curb people's brutality and allow humanity to prosper. Rousseau explains his theory of the inherent goodness of man and society's restrictions in his 1755 treatise Discourse on Inequality. His work The Social Contract (1762) further extolled the individual rights of people and advocated for a limited government that functions in a limited capacity to allow people to exercise their freedom.

Rousseau's novel about two lovers, Julie; or, The New Heloise, published in 1761, became the most popular novel of the 18th century. The next year he published Emile, or on Education, an instructional book that was highly influential and became one of the most important works on raising children. In 1782, he wrote his Confessions, which was an intimate self-reflection on his life. The work expressed many of his regrets and perceived shortcomings, including giving up all his children for adoption. His confessions would become the archetype for the modern-day autobiography. In 1776 Rousseau wrote his last book, Reveries of the Solitary Walker.

Reception

editIn The New York Times, Stacy Schiff found that the biography "is a little spare in the philosophy department". Nevertheless, Schiff concluded, "Rousseau pioneered the concept that ideas fell out of experience, and the erratic, inventive urgency of the life is all here. A delight to read, Damrosch comes as close to Rousseau's authentic self as we are likely to get."[3] Writing for the Washington Post, Michael Dirda applauded Damrosch's literary style: "Damrosch is an academic — a professor of 18th-century literature at Harvard — but he nonetheless writes for ordinary readers, with clarity, a light touch and immense zest." Dirda concluded that the biography "provides an ideal introduction to both this complex man and his troubling ideas. It is an important book, but also a provocative and exceptionally entertaining one."[1] Writing for The Nation, historian David A. Bell criticized the book for not "engag[ing] extensively with [the] historical background, and as a result ... giv[ing] relatively little sense of the Enlightenment as a cultural phenomenon", and for not giving much attention to Rousseau's "relationships with other thinkers" or "with the common reader". Bell also found that the book "largely ignore[d] the broader intellectual reactions that [Rousseau] provoked, including a smoking lava flow of condemnation from the Christian churches".[4] However, Bell found that the biography "succeed[ed] marvelously" in providing a "full, vivid, dramatic and well-informed portrait" of its subject.[4]

The book was a finalist for the 2005 National Book Awards for Nonfiction, with the judges stating that the work was "Witty, pungent, and erudite" and that "Leo Damrosch's Rousseau renders one of the most canonical figures in Western literary and political thought into a full-bodied human, flawed, glorious, searching, and bold."[2]

References

edit- ^ a b Dirda, Michael (January 31, 2024). "A philosopher who wrote with passionate eloquence about the heart and the human condition". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b "Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius". National Book Foundation.

- ^ Schiff, Stacy (November 6, 2005). "'Jean-Jacques Rousseau': An Unruly Mind". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Bell, David A. (November 17, 2005). "Profane Illuminations".