Jawe (Diahoue, Njawe, Oubatch, Ubach) is one of the Kanak languages spoken in the northern province of the largest island of New Caledonia named Grande Terre. Jawe speakers are located along the northeast coast of the island, north of Hienghène and south of Pouébo; primarily in the Cascada de Tao region, Tchambouenne, and in the upper valleys of both sides of the centrally dividing mountain range.[1]

| Jawe | |

|---|---|

| Native to | New Caledonia |

| Region | North Province |

Native speakers | 990 (2009 census)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | jaz |

| Glottolog | jawe1237 |

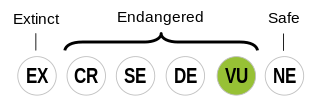

Jawe is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Jawe is one of the 33 Melanesian-Polynesian languages legally recognized by New Caledonia and the Kanak people but it is not one of the most widely used languages amongst the Kanak people, as French is the predominant and official language in New Caledonia.[4]

There are approximately 1,000 native or first language Jawe speakers, and they account for approximately 1 in 45 people in the northern province, 1 in 99 Kanak people, and 1 in 246 people overall amongst the population of New Caledonia, including the surrounding Loyalty Islands.[5][6]

Due to a loss in usage, this language is considered to be in threatened status, but according to a 2009 census, the native-speaking population is increasing.[1]

Classification

editThe New Caledonian languages are most closely related to the languages of Vanuatu, which is also located in the Melanesian sub region of Oceania. Together these languages make up the Southern Oceanic languages which is a linkage to the Oceanic languages and classified under the Austronesian language family.[2] New Caledonian languages are also closely related to Polynesian languages like the Fijian languages, Māori language, Tahitian, Samoan, and Hawaiian.[7]

Oceanic linguists have categorized the New Caledonian languages into two primary groups: the group of languages spoken on the Loyalty Islands, referred to as the Loyalties languages, and the group of languages spoken on the largest island, Grande Terre, called the mainland languages. The mainland languages are further classified regionally between the languages spoken in the southern region and the languages spoken in the northern province.

Jawe is most closely related to the northern languages which are further sub-categorized and/or referenced as two different groups: first are the northernmost languages called the Far North or North Northern group; second is the group of languages that are located just south of the first group and called the North or other northern languages group. Jawe comes from the group of north or other northern languages and is most closely associated to the languages in the surrounding communities around the Hienghene region: Pije, Nemi and Fwai.[3]

Historical impacts on language

editThe New Caledonian languages branched off from the other Oceanic languages after Melanesian people settled in New Caledonia around 3000 bc. The languages evolved under mostly isolated conditions until there was contact with Europeans in the late 18th century which created regular contact form the subsequent trading, migration and eventual colonization. Protestant and Roman Catholic missionaries arrived in New Caledonia in the 1840s and began efforts at conversion; most notably for the north province was Marist mission was set up just north of Pouebo, in Balade.

The French took colonial possession of most of New Caledonia in 1853 and imposed forced labor, limitations on travel, and curfews which lead to Melanesian revolts that were a frequent occurrence until 1917. By 1860 the French had established their authority over the southern part of the mainland and implemented policies that significantly destabilized and altered the lives of Melanesians, including: the confiscation and dispossession of Melanesian lands; regrouping Melanesian tribes; the implementation of the 1887 system of administrative law named the indigénat (native regulations) that was based on the earlier colonial system of forced labor and restricted travel; the imposition of the 1899 Head Tax which made it mandatory for male Melanesians to seek employment from colonial settlers and the colonial government. By the beginning of the 20th century, large regions of land belonging to Melanesians had been confiscated with the inhabitants being forced onto reserves and both the head tax and the indigénat remained in force until 1946.

Migration to New Caledonia from France, New Zealand and Australia occurred regularly throughout the colonial period but was most significant in the post-colonial years surrounding the nickel boom of 1969–72 which brought an influx of white and Polynesian settlers and for the first time, the Melanesians were a minority in their country, although they are still the largest single ethnic group. Presently, education is free and compulsory for ages of 6 to 16 with French being the only language of instruction in government supported schools and syllabus that follows that of the French school system.[8]

Demographics

editPresently, French is spoken in even the most secluded regions and the 2009 census showed that 35.8 percent of people 15 or older claimed they could speak one of the Kanak languages, compared to, 97.3 percent of people 15 or older claimed that they could speak French. Additionally, only 1.1 percent of the population claimed to have no understanding of French.[5][6]

Jawe is considered to be in danger of becoming extinct on the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS), a tool that can be used to measure the potential for endangerment or extinction amongst languages. A language is considered to be in a threatened status when it is used amongst all of the age groups for interpersonal communication but is losing users and is losing the capacity to be taught and learned inter-generationally.[1]

Phonology

editConsonantal system

editThe following section is meant to show the structural changes to the reconstructed Proto-Oceanic consonantal system that lead to the development of the consonants used in Jawe.

Proto-Oceanic uvular *q divided into both *q and *qq in Proto-New Caledonia and eventually developed into velar *k and *kh in Proto-North. The earlier velar sounds of POc became palatal sounds which kept the two groups from merging. The velar k and kh sounds remained in the languages of the Hienghene region.

| Proto-Oceanic | Proto-New Caledonia | Proto-North | Hienghene region | Jawe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uvular *q | *q | *k | k | k |

| uvular *q | *qq(<*q(V)qV) | *kh | h | h |

Proto-Oceanic velar *k divided into *k and *kk in Proto-New Caledonia and eventually developed into palatalized *c and *ch in Proto-North. For the languages of the Hienghene region *c remained unchanged while *ch was weakened to hy or h.

| Proto-Oceanic | Proto-New Caledonia | Proto-North | Hienghene region | Jawe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| velar *k | *k | *c | c | c |

| velar *k | *kk (<*k(V)kV) | *ch | hy, h(i) | hy, h(i) |

Proto-Oceanic laminal *s divided into *s or *ns, and *ss in Proto-New Caledonia, then further developed into stronger apicodental stops of *t̪ or *nd̪, and *t̪h, respectively, in Proto-North. In the languages of the Hienghene region the Proto-North apicodental *t̪ merged with retroflex *ṭ- and intervocalic retroflex lateral -l-.

| Proto-Oceanic | Proto-New Caledonia | Proto-North | Hienghene region | Jawe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| laminal *s | *s, *ns | *t̪, *nd̪ | t, nd, (-l-) | t, nd, (-l-) |

| laminal *s | *ss (<*s(V)sV) | *t̪h | th | th |

Proto-Oceanic alveolar *d (or *r)divided into *ṭ or *nḍ, and *ṭṭ in Proto-New Caledonia, then further developed into *ṭ, *nḍ, (-l-), and *ṭh, respectively, in Proto-North. The split into *ṭ and *ṭh either occurred by devoicing POc*d or strengthening POc *r. In Jawe when *ṭ is in the initial position it has a reflex of ṭ but has -l- as its reflex when in intervocalic position.

| Proto-Oceanic | Proto-New Caledonia | Proto-North | Hienghene region | Jawe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alveolar *d (or *r) | *ṭ, *nḍ | *ṭ, *nḍ, (-l-) | t, nd, (-l-) | t, nd, (-l-) |

| alveolar *d (or *r) | *ṭṭ (<*ṭ(V)ṭV) | *ṭh | th | th |

Proto-Oceanic dental *t split into apicodentals *t̪ and *t̪t̪ in the Proto-New Caledonia reconstruction, then further developed into apicoalveolars *t, or *nd, and *th, respectively, in Proto-North. The transition into apicoalveolar consonants prevented a merger from occurring with POc *s which strengthened to apicodental *t̪.

| Proto-Oceanic | Proto-New Caledonia | Proto-North | Hienghene region | Jawe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dental *t | *t̪, *nd̪ | *t, nd (alveolars) | t, nd/c(i,e), ɲj(i,e) | c, ɲj |

| dental *t | *t̪t̪ (<*t̪(V)t̪V) | *th (alveolar) | th/h(i) | s |

Proto-Oceanic bilapial *p divided into reflexes represented by *p and *pw with each one further splitting into *pp and *ppw, respectively, in Proto-New Caledonian. The consonants *p and *pw are non-aspirates in the Proto-North reconstruction and remain unchanged in Jawe. Consonant *pp becomes aspirate *ph in Proto-North but has weakened to f or vh in all other languages except Jawe and Pwapwa where it remains unchanged. *ppw becomes the labiovelarized aspirate *phw in Proto-North but this has weakened in all languages to fw or hw, specifically hw in Jawe.

| Proto-Oceanic | Proto-New Caledonia | Proto-North | Hienghene region | Jawe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bilapial *p | *p | *p | p | p |

| bilapial *p | *pw | *pw | pw | pw |

| bilapial *p | *pp | *ph | f, vh | ph |

| bilapial *p | *ppw | *phw | hw | hw |

Dialects

editTwo dialects of Jawe have been distinguished by linguists who have noted the usage of aspirated stops or fricatives in a coastal dialect (referred to as CJawe) and the different postnasalized stops pwm, pm, tn, cn, and kn in the upper valley dialect (referred to as UJawe) which gives UJawe post-nasalized consonants.[10]

Morphology

editJawe, like other languages in the northern region of the mainland island, use a number of articles for indicating definiteness and the numerical scope of a noun.

- The singular definite specific article is nei

- The singular definite article is di or dii

- The singular indefinite article is ya

- In articles identifying numerical value the initial marker is the number which is separated by a slash from the article. There is no definite specific article for dual or multiple pluralization.

- The dual definite article is deu/li

- The dual indefinite article is deu/lixen

- The plural definite article is dee/li

- The plural indefinite article is deu/lixen or deu/yaxen.[11]

- Morphemes

| Jawe Word or Phrase | Gloss |

|---|---|

| ŋgo | bamboo |

| ca- | food |

| ndo or ndoo-n | leaf |

| njan | cord |

| yaak | fire |

| yat and yale- | name |

| yaec | storm wind |

| cñe-n | mother |

| ɲ̩jai- and cai- | back |

| pe | stingray |

| pwen | turtle |

| mbwa- | head |

| mbo | smell |

| mwa | house |

| kut | rain |

| kula | shrimp |

| küic | yam |

| kon | sand |

| kaloo- | husband |

| hup | Montrouziera cauliflora plant (only found on New Caledonia) |

| cii- | skin |

| cin | breadfruit tree |

| ciik | louse |

| ciiya | octopus |

| cane- | clitoris or vulva |

| hi- | hand |

| hilec | Morinda citrifolia plant |

| hyane- | contents |

| -nda | upwards |

| nduu- | bone |

| thi- | breast |

| thik | shellfish |

| (ku)raa | blood |

| ndalep | the Erythrina plant |

| the | moss |

| tha | bald |

| that | Pandanus tree |

| thap | coated tongue |

| tho and thoo- | an aigrette or a collection of feathers |

| cali- | a younger sibling of the same sex |

| hie- | older sibling of the same sex |

| calik and ndalik | sea |

| ɲjuu- | woman's skirt |

| hia | yam field |

| hiŋ̩guk | swollen |

| paa- | thigh |

| pangu- | grandson |

| pun or puni- | hair or body hair |

| pwe-n | fruit |

| pwe | fishing line |

| hweet | old banana whose root is eaten |

| yalu | to bail out |

| yalo | to sharpen |

| telii | to tie with a slip knot |

| nde | asks who? |

| nda | asks what? |

| cimwi | to squeeze or to seize or grasp |

| hweli | to press out |

| phe | to carry |

| kalo | to look at |

| koot | to stream |

| huli | to eat sugar cane |

| haloon | to marry |

| cai- | to bite |

| hina | to know |

| cei and hyei | to cut |

| hyeli | to scrape |

| hyoom | to swim |

| -nda | to go up |

| thii | to prick |

| thin | to set fire to |

| tho | to call |

| tena | to hear |

| sai | to pull up |

| phelo | to have something hot to drink |

| phai | to cook |

| hwa | hole, mouth or opening |

Documentation

editThe majority of information that is known about the northern New Caledonian languages is based on the initial work done by French linguists André-Georges Haudricourt and Françoise Ozanne-Rivierre who published the Dictionnaire thématique des langues de la région de Hienghène (Nouvelle-Calédonie): pije-fwâi-nemi-jawe in 1982. The more substantial part of the French language publication is a comparative dictionary of the languages of the Hienghene region containing approximately 4,000 entries, an index with glosses to French and Latin, and which is semantically organized into seven themes: Corps humain, Techniques, Individu-Société, Nature, Zoologie, Botanique, Termes grammaticaux. Also included in the publication is a historical study that shows the phonological relationship of the Hienghene region languages to Proto-Oceanic. The neighboring Caac language, which is classified as a Far North language, was of special interest to the linguists as a source for comparison for the languages being studied.

Some irregularities within the work have been noted by subsequent Oceanic linguists, most notably that the thematic organization is conceptually Western, although the detail still reflects aspects of Kanak life. Another irregularity is that the orthography used is not accompanied with an explanation of how it differs from International Phonetic Alphabet. There is also a lack of sources for which language borrowing from neighboring communities is attributed to. Language borrowing has become the excepted explanation and at least one way that it is known to happen is as a result of regular marriage exchanges with neighboring communities and the subsequent bilingualism that develops.

Linguists have noted a lack of interest in the study of the New Caledonian languages which is primarily attributed to a language barrier due to most Oceanic linguists being English speakers while a majority of the discourse concerning the languages of New Caledonia is in French.[7][13]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Jawe at Ethnologue (Web edition, 2016)

- ^ a b The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database(2008), Greenhill, S.J., Blust. R, & Gray, R.D

- ^ a b See Haudricourt & Ozanne-Rivierre, 1982.

- ^ New Caledonia at CIA Factbook (web version, 2016)

- ^ a b Recensement de la population en Nouvelle-Calédonie en 2009 Institut National de la Statistique ed des Estudes Economiques

- ^ a b World Population Prospects Archived 2013-02-28 at the Wayback Machine(2015 Revision). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- ^ a b Hollyman, K. J. "(Book Review) Dictionnaire thématique des langues de la région de Hienghène (Nouvelle-Calédonie): Pije-Fwâi-Nemi-Jawe: précédé d'une Phonologie comparée des langues de Hienghène et du protoocéanien par Françoise Ozanne-Rivierre". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies [0041-977X] yr:1986 vol:49 iss:3 pg:619 -621

- ^ New Caledonia at Britannica (web edition, 2016)

- ^ a b Ozanne-Rivierre, Françoise. 1995. Structural Changes in the Languages of Northern New Caledonia. Oceanic Linguistics 34—1 (June 1995), pp.44-72 (p.47-49)

- ^ Blevins, Julliette & Andrew Garrett. 1993. The Evolution of Ponapeic Nasal Substitution. Oceanic Linguistics 32—2 (Winter 1993), pp. 199-236 (p.223) University of Hawai'i Press

- ^ Lynch, John. "Article Accretion and Article Creation in Southern Oceanic Languages" in Oceanic Linguistics Vol. 40, No. 2 (Dec, 2001), pp. 224-246 (p.240-241) Published by: University of Hawai'i Press

- ^ Ozanne-Rivierre, Françoise. 1992. The Proto-Oceanic Consonantal System and the Languages of New Caledonia. Oceanic Linguistics 31–2, Winter, 1992 (p.200). University of Hawai'i Press.

- ^ Geraghty, Paul. "(Book Review) Dictionnaire thématique des langues de la région de Hienghène (Nouvelle-Calédonie): Pije-Fwâi-Nemi-Jawe: précédé d'une Phonologie comparée des langues de Hienghène et du protoocéanien par Françoise Ozanne-Rivierre". Oceanic Linguistics, Vol. 28, No. 1, A Special Issue on Western Austronesian Languages (Summer, 1989), pp. 96-101

Bibliography

edit- Haudricourt, André-Georges; Ozanne-Rivierre, Françoise (1982). Dictionnaire thématique des langues de la région de Hienghène (Nouvelle-Calédonie) : pije, fwâi, nemi, jawe. Précédé d'une phonologie comparée des langues de Hienghène et du proto-océanien. Paris: Société d'Etudes Linguistiques et Anthropologiques de France. p. 285. ISBN 978-2852971349.