Jason Sendwe (1917 – 19 June 1964) was a Congolese politician and the founder and leader of the General Association of the Baluba of the Katanga (BALUBAKAT) party. He later served as Second Deputy Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic of the Congo) from August 1961 until January 1963, and as President of the Province of North Katanga from September 1963 until his death, with a brief interruption.

Jason Sendwe | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

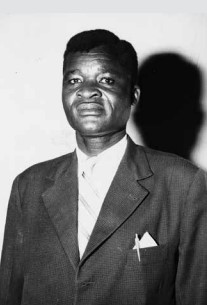

Sendwe in 1960 | |||||||||||||

| 2nd Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo | |||||||||||||

| In office 2 August 1961 – 21 January 1963 | |||||||||||||

| President | Joseph Kasa-Vubu | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Cyrille Adoula | ||||||||||||

| President of North Katanga Province | |||||||||||||

| In office 21 September 1963 – 15 March 1964 | |||||||||||||

| In office 28 April 1964 – 19 June 1964 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||

| Born | 1917 Mwanya, Kabongo Territory, Belgian Congo | ||||||||||||

| Died | 19 June 1964 (aged 46–47) near Albertville, Democratic Republic of the Congo | ||||||||||||

| Political party | Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga | ||||||||||||

| Children | 8 | ||||||||||||

Sendwe was born in 1917 in Mwanya, Kabongo Territory, Belgian Congo, to a ethnic Baluba family. He was educated in Methodist schools and nursing institutions. Unable to become a doctor due to a lack of medical schools in the Congo, he found work as a minister, teacher, and nurse. He became involved in several cultural organisations, and in 1957 founded BALUBAKAT to fight for the interests of the Baluba. He espoused Congolese nationalism and believed that the Congo should remain a united country after Belgian rule. In May 1960, shortly before the country's independence, he was elected to the newly constituted Chamber of Deputies. Sendwe sought to obtain control over the government of Katanga Province, but lost to a power struggle against his rival, Moïse Tshombe, and the Confederation of Tribal Associations of Katanga (CONAKAT) party. Regardless, Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba nominated him for the office of State Commissioner for Katanga.

In early July 1960 Tshombe announced the secession of an independent State of Katanga. Sendwe opposed the breakaway state and rejected Tshombe's entreaties for him to join the rebel government, rupturing relations between the two men. Invested with the responsibilities of State Commissioner by the Senate, Sendwe unsuccessfully attempted to restore central government control over Katanga. After a period of turmoil he was appointed Deputy Prime Minister in August 1961 with the hope that he could use his political influence to win the central government support in Katanga. Four months later he was made Commissioner-General Extraordinaire for the province, nominally giving him complete authority over the area.

Sendwe's political prospects were severely damaged in December 1962 when the Senate censured him and forced his subsequent resignation from the deputy premiership. In early 1963, he increasingly focused his activities in Katanga, as the province acceded to central authority and Tshombe fled into exile. The territory was divided into new political units against Sendwe's wishes. Despite his dissatisfaction, he assumed office as President of North Katanga in September. In January 1964 he lost his position as president of BALUBAKAT. In June Simba rebels overthrew his government and killed him, though it is unclear who held ultimate responsibility for his death. Sendwe's demise greatly demoralised the Baluba, and his reputation drifted into obscurity.

Early life

editJason Sendwe was born in 1917 in Mwanya, Kabongo Territory, Belgian Congo to a Baluba family.[1][2] The Luba were a large ethnic group indigenous to the Katanga and Kasaï regions of the Congo.[3] Sendwe was a childhood friend of Moïse Tshombe.[4] He received six years of primary schooling from Methodists in Kabongo and four years of secondary education at the Kanene Methodist Mission in Kamina.[1] For five years he took nursing courses in Stanleyville and at the École officielle pour Infirmiers à Élisabethville.[5] He completed his studies at the École des Assistants Indigènes de Léopoldville, graduating as a nurse.[1]

His aspirations to become a doctor were curtailed by the lack of medical schools in the Congo.[6] He worked as a minister and teacher at the Kanene Methodist Mission, and in 1942 entered the service of the colonial administration as a clerk. Sendwe later became a nurse and then a medical assistant, working in Élisabethville, Mutshatsha, Kongolo and Kabongo.[2] He was a founding member and treasurer of the Amitiés Belgo-Congolaises cultural organisation, treasurer of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, councillor of the Association Saint-Luc, councillor of the Foyer social Léopold III, and served on the council of the Church of Christ in the Congo.[2][7] Sendwe married and had eight children.[8]

Entry into politics

editIn 1957 Sendwe founded and became president of the Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT), with the stated aim of encouraging unity among the Baluba of the Katanga Province.[9] According to journalist Évariste Kimba, he was able amass much of their support through his "dynamism" and frequent interactions with the population.[10] Three tenants underlined his political philosophy: protection of the Baluba, achievement of Congolese independence, and the primacy of conciliation in settling disputes.[11]

"Sendwe...a practicing Protestant and fine family man, led the BALUBAKAT in the old paternalistic ways of the traditional chiefs."

Thomas Kanza's reflection on Sendwe's nature[12]

In 1958 Sendwe attended the Brussels Expo, working as a medical assistant at the African Personnel Reception Center.[2] Afterwards he joined the short-lived Mouvement pour le Progres National Congolais, a party formed by attendees of the exposition.[13] On 5 February 1959 Sendwe brought BALUBAKAT into Tshombe's Confédération des associations tribales du Katanga (CONAKAT) party on the condition that it be able to maintain a significant amount of autonomy.[14] He initially shared the xenophobic stances of CONAKAT, but soon grew concerned that its hostility toward immigrants would extend to incoming Baluba. Sendwe was also worried by Tshombe's close connections to the Belgians[15] and was repulsed by the prominence of several of his political rivals within the party's ranks.[14] BALUBAKAT began to form two trends, one sympathetic to CONAKAT, and the other supportive of the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC). The latter was led by Sendwe. In October he sent a letter to Baudouin, King of the Belgians, urging him to oppose efforts at "dismantling the immense country" created by his predecessors.[10]

In November 1959 Sendwe withdrew BALUBAKAT from CONAKAT.[16] He subsequently negotiated the formation of a "Cartel Katangais" between BALUBAKAT and two other organisations[17][18] to compete against CONAKAT in the December 1959 municipal elections.[16] Sendwe met with Baudouin on 25 December.[10] By January 1960 Sendwe had decided he would pursue Congolese independence with aim of creating a federal state with a robust central government, in contrast to CONAKAT's vision of a confederation. That month he went to Brussels to participate in the Belgo-Congolese Round Table Conference,[16] a meeting to discuss the political future of the Belgian Congo.[19] The conference resolved with the Belgian government acceding to Congolese demands for the colony's independence on 30 June 1960.[20]

Rise to prominence

editIn the national elections before the Republic of the Congo's independence on 30 June 1960, Sendwe was elected to the Chamber of Deputies with 20,282 votes from the Élisabethville constituency.[1] CONAKAT won a slight majority of the seats in the Katanga Provincial Assembly, and could thus determine the composition of the provincial government. Sendwe ordered the BALUBAKAT deputies to abstain from sitting; when the assembly convened on 5 June it did not have a quorum to vote on the provincial portfolios.[21] CONAKAT offered Sendwe the office of Katanga Vice-president and the responsibility of several ministries, but he refused to negotiate.[2] On 15 June the Belgian Parliament modified the Congo's provisional constitution to reduce the number of deputies necessary for a quorum to vote on a government. Cartel Katangais representatives subsequently declared that they would wait for the Congolese central government's decision after independence.[22] That same day Sendwe signed a deal with MNC leader Patrice Lumumba to create a coalition in Parliament to support a government under Lumumba. In exchange, BALUBAKAT would get some ministerial portfolios and Sendwe would be nominated to be the State Commissioner for Katanga.[a] On 19 June a BALUBAKAT delegation led by Prosper Mwamba Ilunga covertly travelled to Léopoldville to meet with Lumumba. They encouraged him to dismiss Sendwe if he did not follow his instructions, and expressed their disapproval of Sendwe's decision to instruct the BALUBAKAT deputies to boycott the Katanga Provincial Assembly.[24]

On 23 June the Cartel Katangais declared its preferred Katangese government, which placed Sendwe as Provincial President.[25] In the meantime CONAKAT voted in its own government. Despite this, Lumumba, as Prime Minister, nominated Sendwe to be the State Commissioner for Katanga.[15] The President of the Katanga Provincial Assembly, Charles Mutaka, threatened secession if the appointment were confirmed.[26] In early July Tshombe went forward with the secession of the province with Belgian backing but actively sought Sendwe's support, hoping to build a coalition that would bring the latter in as vice-president of an independent Katanga. Sendwe rejected the idea, rupturing relations between them.[15] The Senate initially rejected all of Lumumba's nominees for state commissioner. However, on 22 July the body, in a move meant to convey its wish that central government authority be reestablished in Katanga, voted to confirm Sendwe's appointment, 42 to 4 with 7 abstentions.[27] After assuming the role of State Commissioner of Katanga, Sendwe vainly attempted restoring central government control over the province.[28] His attempts to do so as well as his aim of brokering an understanding between BALUBAKAT and CONAKAT at the national level were frustrated by the Belgian government, which perceived Sendwe as an instrument of the Lumumba Government, with whom they had tense relations.[29]

Sendwe was chosen to lead part of the army into northern Katanga to reestablish the central government's authority, but this plan dissolved following Lumumba's dismissal by President Joseph Kasa-Vubu in September.[15] Lumumba's demise caused political turmoil, and Sendwe was appointed by the Chamber to as rapporteur on a reconciliation commission tasked with brokering a political agreement between Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba.[30] Meanwhile, northern Katangese rejected Tshombe's leadership and the secession in favour of Sendwe, who they saw as a proponent of nationalism and a protector of the Baluba. Sendwe also enjoyed a substantial amount of popularity around Élisabethville, posing a significant political threat to Tshombe. However, many in the central government saw him as having been too close with the deposed prime minister.[15]

On 19 October, three days after Tshombe concluded a deal with Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu to—in Mobutu's words—"neutralise" Lumumba, Sendwe was incarcerated by central government officials. The United Nations (UN) secured his release on the basis of parliamentary immunity. With its sponsorship, Sendwe toured northern Katanga to promote peace, and received an ecstatic welcome from the Baluba.[31] He encouraged the Baluba to maintain public order and place their confidence in the UN. For the most part, his tour improved security in the region,[32] but his presence in Manono from 2–3 November heightened tensions in the area.[33] Tshombe denounced him as a "public danger".[31] While the central government was negotiating the transfer of Lumumba to Katanga (where he would be executed upon arrival), Tshombe repeatedly asked to receive Sendwe. Though initially agreeing to the plan, central government officials later backed away from their commitment to hand him over.[34]

In December Sendwe attended a Francophone-African conference in Brazzaville where foreign diplomats attempted to provide mediation between the Congolese factions.[35] In early 1961 he appealed to the UN to go on another pacification tour of northern Katanga, receiving their approval on 8 January. However, the next day forces of the rival Free Republic of the Congo invaded the area and BALUBAKAT declared its own administration of the region as the "Province of Lualaba".[36] Sendwe attempted to broker a political compromise and secure Belgian political and commercial acceptance of the new province. He celebrated its creation in a tour of the area in February.[37] Meanwhile, he travelled to Belgium in February and in May he participated in the Conference of Coquilhatville,[1] successfully convincing the other Congolese delegates to give recognition to Lualaba.[38] He undertook another pacification trip in northern Katanga in July.[39]

On 2 August a new Congolese central government was formed under Cyrille Adoula. Sendwe was appointed Second Deputy Prime Minister,[40][b] as he was viewed as the only figure with enough political clout in Katanga to challenge Tshombe.[41] Other nationalists in Parliament wanted him to assume the premiership, but he preferred to focus his political energies on Katanga instead of the national level, where he had less support.[42] An état d'exception (state of emergency) was proclaimed on 28 November by the central government in Katanga. Sendwe was appointed Commissioner-General Extraordinaire for the province, nominally giving him absolute authority over the area.[41][c] He devoted much of his time to attending to the needs of Baluba in refugee camps in Élisabethville and Albertville.[44] Between March and July 1962 he attempted to negotiate a deal between the central government and the Katangese secessionists, generally taking a moderate stance and even suggesting a reconciliation between BALUBAKAT and CONAKAT.[45] In July he also came into conflict in the pursuance of his responsibilities with fellow BALUBAKAT member Antoine Omari, who had been tasked by the government with reestablishing local administration, as Omari attempted to grant power to local BALUBAKAT members who wanted to split Katanga Province.[46][47]

Over time the central government hardened its attitude against Katanga, and Belgium gradually withdrew its support for it. With the secession's prospects weakening, Sendwe hoped to obtain control over the province. Though he had the support of most of the Katanga Baluba and the BALUBAKAT deputies in Parliament, the Adoula Government sought to divide Katanga to weaken it. At the same time, BALUBAKAT officials in northern Katanga wanted an exclusive polity in the region under the domination of their own party. The Adoula Government also wanted to use Sendwe vis-à-vis his regional popularity as a counterweight to Tshombe, without granting him control of the entirety of Katanga.[48]

Political demise

editBy the end of 1962 Sendwe was at the peak of his political aspirations, being able to exert great power and influence over the new province of North Katanga (formerly Lualaba).[49][d] However at 22:00 on 23 December,[51] his son became involved in a youth gang street brawl. Sendwe arrived on the scene and ordered some accompanying soldiers to intervene. In the process they assaulted Senator Pierre Medie, who had come to support his own son.[52] On 28 December,[5] in the Senate, Sendwe attempted to defend his actions during the street altercation, being frequently interrupted by angry cries from the majority of the senators.[53] Before he was able to complete his defence, they passed a motion of censure against him, 45 votes to four with four abstentions.[51][e] This formally compelled him to resign as Deputy Prime Minister on 21 January 1963,[47] causing him to withdraw from national to local politics.[49] His departure heralded the removal of the last of the Lumumbists from the government.[55]

In early 1963 Katanga was reintegrated into the Congo as multiple provinces and Tshombe agreed to cooperate with government officials. Sendwe vied for control of the region, leading to ethnic clashes in Jadotville in April in which approximately 74 people were killed.[56] Nevertheless, he negotiated a deal with Tshombe's Minister of Interior, Godefroid Munongo, to allow for the return of the Baluba in the Élisabethville refugee camp to their homes.[44] After Tshombe fled the country, Sendwe sought to extend his constituency beyond the Baluba to establish control over the whole of Katanga.[57] He questioned the legality of the existence of North Katanga as a separate political entity and continued to push for the reunification of Katanga Province. However, his removal from the central government and the rejection of his unity proposal by the North Katanga Provincial Assembly forced him to relax his goals.[54][f] On 18 May the état d'exception was retracted in Katanga and he was discharged from his post as Commissioner-General Extraordinaire.[46]

In July Sendwe moved to Albertville to rebuild his political base.[58] He blocked the repatriation of the Baluba refugees in the local camp; the UN feared this was so he could use the refugees to boost his support.[59] The Adoula Government was pleased by Sendwe's relocation, wanting to be rid of him in Léopoldville. Soon after he arrived, rumours emerged that North Katanga Provincial President Mwamba Ilunga had arrested him. This sparked unrest as rural Baluba and customary chiefs began to protest, triggering Mwamba Ilunga's resignation.[60][g] BALUBAKAT deputies in Parliament lobbied for Sendwe to replace him, and at an August BALUBAKAT party congress—with Mwamba Ilunga's acceptance—ruled that Sendwe should be given the provincial presidency. On 21 September the provincial assembly elected Sendwe President of North Katanga Province and invested him with the public health portfolio.[63] The situation in North Katanga under Sendwe quickly became disastrous, driven by his alcoholism, poor management of public funds, nepotism, lack of a government programme, and numerous attempts to use his position to deprecate his rivals. Problems were exacerbated by the withdrawal of UN peacekeeping forces and destructive floods. By the end of the year corruption was rampant, civil servants were receiving pay on an irregular basis, and much of the population was impoverished. Further, BALUBAKAT became an increasingly ethnic, exclusively Baluba organisation.[64]

Sendwe's management of North Katanga perturbed other government officials[64] and Adoula began seeking a way to remove him from office. Fortunat Kabange Numbi, an ally of Adoula and a BALUBAKAT deputy in Parliament, considered a solution with Albertville businessmen that involved granting Sendwe an executive position at a company in exchange for his resignation. The proposal was rejected by Mwamba Ilunga and others, who chose instead to revise BALUBAKAT's organisation. They changed the party's name to Parti Progressiste Congolais (PPCo) to distance it from its ethnic connotation and called a congress in January 1964 to vote in new leadership. Sendwe attended the first meeting but then denounced the event and banned it, which was reversed at the order of the Deputy Prime Minister.[65] Sendwe lost his seat as party president in a vote of 28–3. He failed to secure any significant party office,[66] and was relegated to the position of adviser to the PPCo.[67] On 15 March the provincial assembly, in a special session sponsored by President Kasa-Vubu, dismissed Sendwe from his post as Provincial President and replaced him with Kabange.[h][67][69]

Sendwe argued on legal technicality that his removal was unlawful,[70] denounced the PPCo, and declared that only his government had popular support. On 27 April the provincial assembly reached a compromise, re-electing Sendwe President of North Katanga but revising his government, stripping him of the public health portfolio and making Kabange Provincial Vice-president.[67] He was re-inaugurated the following day. He pledged to strengthen North Katanga's institutions and territorial integrity, protect political parties that sought to further "superior interests" of the Congo, and encourage friendly relations between BALUBAKAT and CONAKAT. He also announced his intention to increase economic cooperation with other provinces and establish cooperatives for merchants and consumers.[68] Meanwhile, a radical leftist BALUBAKAT activist, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, planned a rebellion in North Katanga to overthrow Sendwe and Kabange.[71]

Death

edit"Jason had battled so long for his Baluba idea...had seen victory, worn the leopard skin, been carried on the shoulders of his people...become a minister, touched power and money, lost his aura and perished."

British journalist Ian Goodhope Colvin[72]

On 27 May 1964 a coup in Albertville by Simba rebels, led by Kabila, overthrew Sendwe's government.[73][74] Sendwe was accused of embezzling public funds and detained.[75] While the rebel leaders debated what to do with him, including executing him, Sendwe escaped,[74] and spent the next few days trying to reestablish his authority as the rebels' control crumbled.[76] On 30 May, a small government force under the command of Colonel Louis Bobozo recaptured the town and recovered Sendwe—who claimed to have been nearly buried alive by the rebels.[77] Sendwe was under the false impression that Mwamba Ilunga had stoked the rebellion and had him arrested.[78][i] Unrest persisted in Albertville.[77] Sendwe failed to calm the situation and instead gave statements attacking his rivals and non-Baluba ethnicities.[79] On 19 June the population revolted and the government evacuated. Sendwe attempted to flee but was hampered by government troops and was killed by rebels.[77] Questions about his death were raised in several newspapers, and the central government released an official report about it two weeks later.[80]

There are various theories about how and why Sendwe was killed. According to journalist Ian Goodhope Colvin, Sendwe was driving towards Fizi with an American missionary when his car was stopped by Simba rebels. In this account, his police escort fled and he and his companion were murdered.[72] According to political scientist Jean Omasombo Tshonda, he was arrested by ANC soldiers at Muswaki while attempting to escape by train and then forced to return to Albertville. Driving with several relatives, he went into the city to try and calm the Simbas, assuring them of his Lumumbist credentials by shouting (in a reportedly drunken manner), "Lumumba is my brother! Mulele is my brother! All of you, you are my brothers!"[81] The rebels then shot him and some of his companions on Kangomba hill.[81]

Political scientist Erik Kennes examined various testimonies concerning Sendwe's death. One witness held Saidi Saleh Mukidadi, a local politician, responsible for the death. Political scientist Kabuya Lumuna Sando concluded that ANC defectors shot Sendwe. Kennes questioned the validity of the latter claim, noting that most ANC elements had retreated from the area and that no other witnesses reported dissident soldiers forming part of the Simbas' ranks. Simba leader Gaston Soumialot accused Mobutu of organising the murder. Other observers believed that the ANC soldiers' actions indicate central government involvement. Kabuya, noting the allegedly newer clothing worn by the soldiers who had prevented Sendwe's departure, posited that the ANC men were clandestine government operatives. He argued that Mobutu, head of the ANC at the time, wanted Sendwe dead to make rapprochement with Tshombe easier.[81] There is a rumour that the execution was carried out by several Bayombe under orders from Kabila.[82] Kennes reasoned that this was unlikely because Kabila did not have Sendwe killed the first time Albertville was seized[j] and was not present when the city fell on 19 June.[83]

Legacy

editThroughout his career, Sendwe was the undisputed national leader of the Katangese Baluba[84] and the primary opponent of Tshombe during the Katangese secession.[2] Historian Reuben Loffman credited him with hastening the end of the secession through his success in negotiating with national and international figures.[85] According to British journalist Ian Goodhope Colvin, Sendwe's death deprived Adoula of a figure who could guarantee him Katangese support, forcing him to welcome Tshombe back into the country.[86] His murder also disillusioned many Baluba in North Katanga with the Simbas' cause, and as a result many abstained from joining their rebellion.[83][87] BALUBAKAT collapsed in his wake.[88] In November 1966 Mobutu, having become president of the Congo, posthumously awarded Sendwe for dying "in defence of the country's honour".[89] An avenue and a hospital in Lubumbashi were named after him.[82][90]

After his death, Sendwe drifted into obscurity and by the 21st century there was little memory of him in northern Katanga.[84] The Union des fédéralistes et des républicains indépendants (UFERI) recalled his legacy in its rhetoric. Due to the party's militant reputation, the public associated UFERI with the violent actions of BALUBAKAT, thus limiting its ability to proliferate a positive image of Sendwe.[91] In 2011 a congress of the "Luba People" declared that Sendwe was among their "valiant martyrs".[92] There is little study of him in Congolese historiography.[93]

Notes

edit- ^ A state commissioner was appointed by the head of state with the consent of the Senate to represent the central government in each province. Their main duties were, according to the constitution, to "administer state services" and "assure coordination of provincial and central institutions."[23]

- ^ He served alongside Antoine Gizenga, who was First Deputy Prime Minister in the government.[40]

- ^ The position of commissioner-general extraordinaire was distinct from the office of state commissioner. The former were appointed by Adoula's government on several occasions to shore up its own position and counter dissension in the provinces.[43]

- ^ Administration and governance never truly materialised in Lualaba; it was not until September 1962 that a government was formally installed in the region when it was established as North Katanga.[50]

- ^ Verhaegen gave the date of censure as 26 December.[54] Kennes characterised the street brawl as a "grotesque miscellaneous incident" used as a "pretext" to censure Sendwe.[47]

- ^ Sendwe never believed that Katanga should remain subdivided, but he was willing to forgo his wish for a time in order to quickly secure regional power.[41]

- ^ Willame stated that Sendwe had forced Mwamba Ilunga's resignation.[49] Mwamba Ilunga and Sendwe had a complex party rivalry that emerged in 1960. While Sendwe was the leader of BALUBAKAT, Mwamba Ilunga had led the anti-Tshombe rebellion in northern Katanga from 1960 to 1962.[61] Mwamba Ilunga felt Sendwe had not done enough to assist the insurgency and disapproved of his attempts to dissolve North Katanga.[55] He was also a radical progressive, whereas Sendwe was more moderate.[62]

- ^ Prosper Mwamba Ilunga, then President of the North Katanga Provincial Assembly, maintained that the censure motion was not a "coup" but merely the exercise of the assembly's responsibility to check executive power.[68]

- ^ Mwamba Ilunga had actually been detained by the rebels and strongly denied having anything to do with the rebellion.[78]

- ^ According to one witness, Kabila actually stated his opposition to Sendwe being executed during Albertville's initial fall.[74]

Citations

edit- ^ a b c d e CRISP 1961, paragraph 83.

- ^ a b c d e f Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 241.

- ^ Hoskyns 1965, p. 7.

- ^ Gerard & Kuklick 2015, p. 131.

- ^ a b Gérard-Libois 1966, p. 301.

- ^ Legum 1961, p. 101.

- ^ Chomé 1966, p. 75.

- ^ Merriam 1961, p. 138.

- ^ O'Ballance 1999, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 240.

- ^ Sendwe, le Heros Indesirable 1989, p. 50.

- ^ Kanza 1994, p. 35.

- ^ Lemarchand 1964, p. 281.

- ^ a b Lemarchand 1964, p. 241.

- ^ a b c d e Gerard & Kuklick 2015, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Hoskyns 1965, p. 26.

- ^ Lemarchand 1964, p. 299.

- ^ Kanza 1994, p. 134.

- ^ Hoskyns 1965, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Hoskyns 1965, p. 40.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 325.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 326.

- ^ Lemarchand 1964, p. 216.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 177.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Gérard-Libois 1966, p. 85.

- ^ Bonyeka 1992, p. 135.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 212.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 178.

- ^ Hoskyns 1965, p. 219.

- ^ a b Gerard & Kuklick 2015, p. 133.

- ^ Hoskyns 1965, p. 251.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 191, 195.

- ^ Gerard & Kuklick 2015, p. 197.

- ^ Hoskyns 1965, p. 275.

- ^ Gerard & Kuklick 2015, p. 187.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 203.

- ^ Colvin 1968, p. 66.

- ^ a b Hoskyns 1965, p. 377.

- ^ a b c Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Sendwe, le Heros Indesirable 1989, p. 72.

- ^ Young 1966, pp. 653, 655.

- ^ a b Kennes 2009, p. 219.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 233–234.

- ^ a b Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Kennes 2009, p. 235.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 218, 232.

- ^ a b c Willame 1972, p. 50.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 220.

- ^ a b Bonyeka 1992, p. 327.

- ^ Young 1965, p. 364.

- ^ Young 1965, p. 365.

- ^ a b Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 222.

- ^ a b Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 223.

- ^ Kennes & Larmer 2016, p. 63.

- ^ Willame 1972, p. 55.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 244.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Olorunsola 1972, p. 250.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 211.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 245.

- ^ a b Kennes 2009, p. 246.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Young 1965, p. 382.

- ^ a b c Kennes 2009, p. 248.

- ^ a b Sendwe Installed as Nord Katanga Premier, Élisabethville: Congo Domestic Service, 5 May 1964

- ^ O'Ballance 1999, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Young 1965, p. 591.

- ^ Kennes 2009, pp. 249, 251.

- ^ a b Colvin 1968, p. 168.

- ^ Hoskyns 1969, p. xii.

- ^ a b c Kennes 2009, p. 265.

- ^ Colvin 1968, p. 159.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 266.

- ^ a b c O'Ballance 1999, p. 73.

- ^ a b Kennes 2009, p. 267.

- ^ Kennes 2009, p. 268.

- ^ Sendwe, le Heros Indesirable 1989, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 230.

- ^ a b Rahmani 2007, p. 192.

- ^ a b Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 231.

- ^ a b Omasombo Tshonda 2014, p. 251.

- ^ Loffman 2020, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Colvin 1968, p. 160.

- ^ Colvin 1968, p. 173.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2014, pp. 235, 251.

- ^ Posthumous award for Jason Sendwe, Kinshasa: BBC Monitoring, 18 November 1966

- ^ Fabian 1990, p. 139.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 659.

- ^ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, pp. 603, 605.

- ^ Loffman 2020, pp. 263–264.

References

edit- Bonyeka, Bomandeke (1992). Le Parlement congolais sous le régime de la Loi fondamentale (in French). Kinshasa: Presses universitaire du Zaire. OCLC 716913628.

- Chomé, Jules (1966). Moïse Tshombe et l'escroquerie katangaise (in French). Brussels: Éditions de la Fondation J. Jacquemotte. OCLC 919889.

- Colvin, Ian Goodhope (1968). The rise and fall of Moise Tshombe: a biography. London: Frewin. ISBN 978-0-09-087650-1. OCLC 752436625.

- Fabian, Johannes, ed. (1990). History from Below: The Vocabulary of Elisabethville by André Yav: Texts, Translation, and Interpretive Essay. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-9-0272-5227-2.

- Gerard, Emmanuel; Kuklick, Bruce (2015). Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72527-0.

- Gérard-Libois, Jules (1966). Katanga Secession. Translated by Young, Rebecca. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. OCLC 477435.

- Hoskyns, Catherine (1965). The Congo Since Independence: January 1960 – December 1961. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 414961.

- Hoskyns, Catherine (1969). The Organization of African Unity and the Congo Crisis, 1964–65: Documents, Issue 1. Dar es Salaam: Institute of Public Administration, University College. OCLC 923596549.

- Kanza, Thomas R. (1994). The Rise and Fall of Patrice Lumumba: Conflict in the Congo (expanded ed.). Rochester, Vermont: Schenkman Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87073-901-9.

- Kennes, Erik (2009). Fin du cycle post-colonial au Katanga, RD Congo. Rébellions, sécession et leurs mémoires dans la dynamique des articulations entre l'Etat central et l'autonomie régionale 1960–2007 (PhD thesis) (in French). Université Laval. OCLC 1048412016. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Kennes, Erik; Larmer, Miles (2016). The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa: Fighting Their Way Home. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-2530-2150-2.

- Legum, Colin (1961). Congo Disaster. Baltimore: Penguin. OCLC 586629.

- Lemarchand, René (1964). Political Awakening in the Belgian Congo. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 905074256.

- Loffman, Reuben A. (2020). "'My Training Is Deeply Christian And I Am Against Violence': Jason Sendwe, The Balubakat, And The Katangese Secession, 1957–64". The Journal of African History. 61 (2): 263–281. doi:10.1017/S002185372000033X. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 225646826.

- Merriam, Alan P. (1961). Congo: Background of Conflict. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. OCLC 424186.

- O'Ballance, Edgar (1999). The Congo-Zaire Experience, 1960–98 (illustrated ed.). Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-2302-8648-1.

- Olorunsola, Victor A. (1972). The Politics of Cultural Sub-nationalism in Africa. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books. OCLC 915692187.

- Omasombo Tshonda, Jean, ed. (2014). Tanganyika : Espace fécondé par le lac et le rail (PDF). Provinces (in French). Tervuren: Musée royal de l'Afrique centrale. ISBN 978-9-4916-1587-0.

- Omasombo Tshonda, Jean, ed. (2018). Haut-Katanga : Lorsque richesses économiques et pouvoirs politiques forcent une identité régionale (PDF). Provinces (in French). Vol. 1. Tervuren: Musée royal de l'Afrique centrale. ISBN 978-9-4926-6907-0.

- "Onze mois de crise politique au Congo". Courrier Hebdomadaire du CRISP (in French). 120 (120). Centre de recherche et d'information socio-politiques: 1–24. 1961. doi:10.3917/cris.120.0001.

- Rahmani, Moïse (2007). Juifs du Congo: la confiance et l'espoir (in French). Brussels: Institut Sépharade européen. ISBN 978-2-9600-0283-6.

- "Sendwe, le Heros Indesirable?". Les Cahiers du CEDAF (in French). Brussels: Centre d'étude et de documentation africaines. 1989. ISSN 0250-1619.

- Willame, Jean-Claude (1972). Patrimonialism and Political Change in the Congo. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0793-0.

- Young, Crawford (1965). Politics in the Congo: Decolonization and Independence. Princeton: Princeton University Press. OCLC 307971.

- Young, Crawford (1966). "Constitutionalism and Constitutions in the Congo". In Leibholz, Gerhard (ed.). Jahrbuch des Offentlichen Rechts der Gegenwart. Neue Folge. Vol. 15. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783166159522.