James Onque Scott Jr.[a] (October 17, 1947 – May 8, 2018) was an American boxer and convicted murderer. He became the second-highest-ranked contender in the World Boxing Association's (WBA) light heavyweight division while incarcerated at Rahway State Prison in Avenel, New Jersey. Scott fought a total of 22 professional fights. Eleven of those fights were contested while he was in prison, and Scott earned pay and WBA rankings from many of those fights, which was considered controversial.

James Scott | |

|---|---|

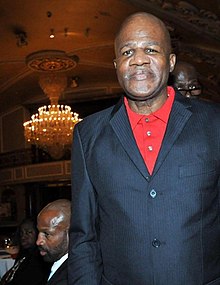

Scott at the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame in 2012 | |

| Born | James Onque Scott Jr. October 17, 1947 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | May 8, 2018 (aged 70) |

| Other names | Great |

| Statistics | |

| Weight class | Light heavyweight |

| Height | 184 cm (6 ft 0 in) |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 22 |

| Wins | 19 |

| Wins by KO | 11 |

| Losses | 2 |

| Draws | 1 |

Scott was born in Newark, New Jersey, and spent much of his life in prison from the age of 13. After taking up boxing as an amateur in Trenton State Prison, he was granted parole to work as a boxer for a manager in Florida. He fought 11 professional fights in Miami. While on a visit to New Jersey, in violation of his parole, he was arrested and charged with the murder of Everett Russ, as well as armed robbery. Convicted of the robbery but with a hung jury on the murder charge, Scott was sent back to prison in New Jersey. After being transferred to Rahway State Prison, Scott formed the Rahway State Boxing Association with prison warden Robert Hatrak, and was allowed to continue boxing professionally at Rahway after connecting with promoter Murad Muhammad.

Muhammad convinced Eddie Gregory, the WBA number 1 contender for the light heavyweight championship, to fight Scott at Rahway in a match televised by HBO. Despite being an underdog, Scott won the fight, leading to him being ranked by the WBA. He fought several more nationally televised matches and rose as high as number 2, but was later stripped of the ranking because of his criminal record and incarceration. After losing his rank and a brief retirement, Scott defeated another number 1 contender in Yaqui López.

After suffering his first loss more than five months after the López fight, Scott was retried for the murder of Russ and was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. He fought twice more, winning the first fight and losing the second. Scott was paroled in 2005 after serving 28 years. He was inducted into the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame in 2012, and died in 2018.

Early life

editScott was born on October 17, 1947, to Ursaleen and James Onque Scott, Sr., in Newark, New Jersey. He was the second of twelve siblings. Scott grew up in various areas of Newark, including the Felix Fuld public housing complex and later in the central ward.[2] In 1978, he described his family as "a typical Black family." He also stated that his parents were divorced and that his mother was on welfare. Scott's brother Malcolm was serving life in prison for murder. According to Scott, "I wasn't attracted to pimps or narcotic dealers; I was attracted to the gangs and their leaders."[3] Scott was given his first pair of boxing gloves by his uncle at age 10.[4]

According to Scott, his formal education stopped at seventh grade.[5][6] He spent much of his time behind bars starting at the age of 13, when he was sent to a reformatory for truancy. At the age of 18, he was declared an incorrigible and sent to Trenton State Prison. While at Trenton, Scott befriended former Army boxer Al Dickens, who was serving a 51-year sentence for armed robbery. Dickens claimed that he convinced Scott to consider boxing instead of "running around breaking heads with an iron pipe".[7] One of Scott's early amateur fights at Trenton was against Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, against whom he lasted three rounds.[3]

Scott stated that he only pursued boxing seriously after being released in 1968 and subsequently being arrested and convicted of armed robbery. He was sentenced to 13 to 17 years in prison. During this time, Scott became the light heavyweight champion of the New Jersey prison system. According to Pat Putnam of Sports Illustrated, Scott "destroy[ed] opponents until there were no more challengers".[7]

Professional career

editParole and initial fights

editDuring his time in prison, Scott sent letters to various boxing promoters and reached out to them via collect calls. He was offered management by an architect named Murray Gaby, who was based in Miami. Gaby made arrangements using political connections to have Scott paroled and allowed to live in Florida. On January 8, 1974, Scott was granted work parole. He trained at the 5th Street Gym, the same gym where Muhammad Ali trained, and fought at the Miami Beach Auditorium. According to Ali's personal physician, who was present at Scott's first sparring session, Scott did not have money and arrived in a pair of cut-off denim shorts and basketball shoes, and had to have boxing gear put together from available equipment at the gym. Gaby said of Scott's performance in his first sparring session, "When Scott started throwing punches, there was dead silence in the gym. Other fighters stopped and watched. He went two rounds, had the guy out on his feet. Everybody gave him an ovation. Very dramatic."[4]

Scott's first professional fight was against John L. Johnson, who was undefeated at the time. He won the fight and handed Johnson his first loss. Scott fought twice the next month, defeating both opponents Hydra Lacy and Willie "The Invader" Johnson. As Scott defeated more and more opponents and subsequently fought in the main event, Gaby recalls that it was becoming more difficult for the promoter to find opponents willing to fight Scott. During this time in his life, Scott found adjusting to life outside of prison to be difficult, oftentimes being confrontational with others. He found it difficult to cope or communicate his feelings, except to his common-law wife.[4]

Having won his first eight fights, Scott was ranked as the number 8 light heavyweight contender according to boxing publication The Ring. In his next match, he fought to a draw against Dave Lee Royster. In the sixth round of the fight, Royster headbutted Scott, and Scott responded with a low blow, resulting in the referee deducting two points from Scott. Royster headbutted Scott again in the eighth round and cut him open above the right eye with the blow. Neither headbutt by Royster resulted in a points deduction.[4] Scott would later claim that he was not inspired to win the fight because he did not receive a letter before the bout from Dickens, who had written to Scott before every professional fight with a plan to defeat his opponent.[8] After the bout, Scott's promoter Chris Dundee called out Bob Foster and publicly offered him $100,000 for a fight with Scott.[4][9]

Scott fought twice more in Miami, earning two more victories. At this point, he had earned approximately $15,000, was living with a woman in an apartment, and had a vehicle.[4] Scott also had a title bout scheduled against John Conteh, the World Boxing Council (WBC) light heavyweight champion, with a $100,000 purse.[7] Despite warnings from Gaby and that it was a parole violation, Scott was driving to Newark for visits home.[4]

Arrest for murder and armed robbery

editWhile in New Jersey on a visit to the state on May 8, 1975, Scott was arrested and charged with murder and armed robbery. Sources vary on how Scott was arrested. In one account, Scott heard that Newark police wanted to speak with him. Deciding not to speak with an attorney first, Scott went to the Newark police headquarters.[4] In another account, Scott was picked up by the police for a parole violation.[7][8] After initially being held as a material witness, he was arrested.[7] According to Scott, the arrest occurred the day before his fight with Conteh was to be announced at a press conference.[7]

According to the Essex County prosecutor's office, around midnight on May 7, Scott and others with him picked up Everett Russ,[b] who was standing outside a bar with a friend.[4] Scott asked Russ to take him to a drug dealer,[10] so Russ led Scott to an apartment belonging to Leo Skinner, who planned to buy drugs from a building next door. While in the next building, Scott, Russ, Skinner, and William Spinks—one of the men traveling with Scott—took the elevator up but held it for Yvonne Barrett, who was headed to the same apartment they were. Skinner did not want a crowd at this apartment, so he stopped the elevator at the eighth floor. Spinks then pulled out a handgun and ordered Barrett and Skinner out; Scott stepped off as well, while Russ took the elevator down to wait in the car with another member of Scott's group. Scott received the gun from Spinks and pistol-whipped Skinner, ordered him to strip,[4] and threatened to throw him off the building over concerns he would tell police.[10] Afterward, Spinks pointed the gun at Barrett and took her to her sister's tenth-floor apartment, where $283 and bags containing a white powder substance were stolen.[4] Scott then shot Russ in his car to prevent him from telling police.[10] Russ' body was pushed out of the car, which then sped off, and a nearby motorist wrote down the license plate number, which was that of Scott's car. Newark police located the car and found blood stains and bullet holes.[4]

Scott's version of events varies based on the source. In one account, he stated that he let Spinks borrow the car, and that Spinks partnered with someone from Newark with the nickname "Black Jack", whom Scott stated that he resembled. He also alleged that Newark police were conspiring against him.[4] In another account, Scott claimed he was taking the fall for the robbery for a friend and refused to talk about who borrowed his car, saying, "[t]errible things happen to stool pigeons" (informants).[3][8] Spinks was killed in an armed robbery one month later, before he could speak to police about Russ' death. Skinner stated that while "Black Jack" and Scott did look alike, he identified differences in their appearances and identified Scott as the man who beat him.[4]

In March 1976, Scott was found guilty of armed robbery,[7] but the jury was hung on the murder charge. As Scott was a repeat offender, judge Ralph L. Fusco sentenced him to 30 to 40 years in prison. Initially imprisoned at Trenton, he was transferred to Rahway State Prison on May 27, 1977. He was assigned the inmate number 57735.[4]

Rahway State Boxing Association and fight with Eddie Gregory

editAt Rahway, the prison warden was Robert Hatrak, who had a reputation considered controversial for sympathy toward inmates and an openness toward rehabilitation.[4] Several programs aimed at rehabilitation were operated by Hatrak, including vocational training such as automotive repair and barbershop skills,[11] as well as a singing group and a "scared straight" program.[2] He then conceived of a boxing program, not simply for recreation but where inmates could train to be fighters, corner men, referees, and cutmen as a profession. Upon hearing that Scott was being transferred to Rahway, Hatrak planned to partner with him to utilize Scott's connections in the sport.[11] Scott was placed in charge of the new Rahway State Boxing Association. Inmates in the program received pay and credit toward a reduction of their sentence or parole.[4] By 1980, the program had over 75 members, screened by inmates, and held between 40 and 50 fights per year. According to Scott, not one of his program members had ever been in trouble since being in the program, which he attributed to the amount of time his members spent on boxing.[12]

Scott's training regimen at Rahway was intense, and other inmates trained with him as well. He would begin by running for an hour every morning in the prison yard;[7] according to one inmate, he was so focused that he would not break formation with the inmates running with him.[11] He would then do a thousand pushups.[5] According to Dickens, who was now serving time in Rahway with Scott, he estimated in 1978 that Scott had run nearly 900 miles in total, performed 51,000 pushups, 16,000 situps, and completed his daily routine with speed bag and heavy bag training. Scott would also spar with inmates and others as part of the program, but problems were found in locating sparring partners. Trenton State Prison's heavyweight champion was brought to Rahway to spar, only to have Scott break three of his ribs. Dave Lee Royster, who fought Scott to a draw in Miami and was an outside visitor, was knocked out by him during sparring and did not return.[7] While in prison, Scott received regular visits from his wife and three children, and spent time reading books such as the Quran, Etiquette by Amy Vanderbilt, and Fyodor Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment.[3] He also earned 20 college credits.[11]

Seeing the progress of the boxing program, Hatrak extended an offer to Scott to allow him to continue his professional boxing career if he could secure a promoter.[4] However, Scott could not receive temporary release from the prison for fights unless he was a minimum-security prisoner, so all of the fights would have to take place at the prison.[5] Scott began making phone calls and writing letters, including to promoters Bob Arum and Don King.[4] An inmate at Rahway[c] reached out to Murad Muhammad, a boxing promoter. Muhammad came to Rahway and met with Scott, and marveled at his physique. According to Muhammad, he asked Scott if he could fight, and Scott answered, "Yes, I can fight. Can you promote?" Muhammad identified Scott's skill at body punching and called him "the Great Scott", his boxing nickname.[11] Muhammad arranged Scott's two first professional bouts in Rahway, both of which were not televised. In those fights, Scott defeated Diego Roberson and Fred Brown by knockouts. For the Brown fight, Scott earned $600.[4]

Muhammad began work on a major fight for Scott against Eddie "The Flame" Gregory, who was then the World Boxing Association (WBA) number 1 light heavyweight contender. As Rahway's prison auditorium would only hold 450 people, Muhammad needed to find a television network willing to host the fight, so he went to HBO. According to HBO's sports department head at the time, Dave Meister, he found the idea of the fight at Rahway "both off-putting and intriguing and enticing".[11] In addition to securing HBO, Muhammad offered $15,000 to Gregory for the fight, while Scott was scheduled to make $2500.[4] Gregory was lined up to make money from this fight in preparation for a bout against WBA light heavyweight champion Mike Rossman.[9]

Though initially scheduled to be 10 rounds, the bout was set for 12 rounds only five days before the fight.[8] On fight day, October 12, 1978,[11] Rahway's auditorium was at full capacity, with an additional 1,150 inmates watching on screens in the drill hall. HBO Sports sent Don Dunphy, Larry Merchant, and Sugar Ray Leonard to commentate the fight.[4][9] Gregory was a 4:1 favorite in betting odds, while inmates bet cartons of cigarettes on similar lines.[9] Scott came out swinging at the start of the fight, and made a bump under Gregory's eye in the fourth round. According to Scott, he then realized he had to pace himself because this fight was likely to go the full scheduled 12 rounds. During the last round, Gregory's corner screamed at him to go for a knockout. The bout ended without one and went to the judge's scores, where all three judges awarded the victory to Scott.[7]

After the fight, Scott called out Rossman. Rossman's father and manager, who was in attendance, said, "It's going to take an awful awful lot of money before I'll let my son in the same ring with that monster."[7] Scott identified that money would be a factor in his ability to compete for a championship.[8] He received his first ranking from the WBA for the victory.[13] In 2014, Harold Lederman, one of the judges of the fight, recalled, "On that one day when he beat Gregory, he was the best light heavyweight I ever saw. I never saw a performance like that — anywhere. I don't think Bob Foster was as good as that. I don't think Archie Moore was that good."[4]

Nationally televised bouts and WBA ranking

edit"My image as a public figure is not good because I'm in prison, I know that. But think back to when there was a mass exodus to the West when they found gold out there. The gold was in the streams. The gold was in the mud. That's what people in the prison houses are like. People here write. People here draw. People here sing. These are the dirtiest places in the country, the prison houses, but that doesn't mean there aren't people here who can do things."

Following his bout with Gregory, Scott had fights hosted on national television. In his first fight after the win against Gregory, Scott defeated Richie Kates by TKO in the 10th round. When asked if he thought the referee did the right thing in stopping the fight, Scott said, "Yes, I do. I was trying to kill him." Scott earned $8000 for the fight, 10% of which was donated to a crime victims' fund.[14] A month after the Kates fight, Hatrak was reassigned and no longer was the warden at Rahway. The new warden, Sidney Hicks, was a guard who had pressed assault charges on Scott at Trenton State Prison for hitting another inmate with a pipe. Shortly after Hatrak was replaced, Scott hired an attorney with what money he had and appealed to be released on bail. This request was denied.[4]

Scott was still allowed to fight professionally after Hatrak's departure. His next fight against Bunny Johnson, aired nationally on NBC, resulted in Scott winning by knockout when Johnson retired at the end of the seventh round.[15] Ranked number 3, Scott defeated Italian light heavyweight champion Ennio Cometti at the end of the fifth round when a prison physician stopped the fight because of a cut over Cometti's left eye.[16] In his entire career, at least four of Scott's professional bouts held in prison were broadcast by NBC Sports, two by CBS Sports and one by HBO.[17] ABC Sports declined to provide Scott with national television coverage due to his felony conviction and incarceration.[17] Scott was ranked as high as number 2 in the WBA rankings. However, controversy began over whether he should be allowed to fight and make money while incarcerated. While Scott was paid for his fights, his earnings were sent to the New Jersey Department of Corrections, and he was given strict limitations on how he could use the money. Approved uses included hiring attorneys for his appeals and paying back his public defenders, donations to a crime victims' fund, and training expenses.[11] Scott said of the situation in a 1980 phone interview with boxing writer Bernard Fernandez, "A lot of people resented the idea of my making money while I was in prison. They didn't feel I was being punished enough. What am I going to spend it on, anyway? People on the outside just want the people on the inside to be punished all the time."[9]

Loss of ranking and fight with Yaqui López

editScott's next fight was scheduled for December 1, 1979, against Yaqui López, the WBA number 1 contender for the light heavyweight championship. Shortly before the fight, WBA light heavyweight champion Víctor Galíndez was stripped of the title, so Muhammad asked the WBA if Scott's fight with López could be a 15-round bout for the championship. Then, in September 1979, the WBA decided to reconsider whether Scott should have a ranking at all based on his criminal record.[4] The major concern at the WBA was the championship being held by someone in prison;[4][11] the competing WBC had never ranked Scott due to his incarceration.[18] According to boxing promoter Bob Arum, the WBA had only just found out that Scott's incarceration was scheduled for 30 to 40 years.[13]

The WBA removed Scott from its rankings in October 1979.[19][20] The vote on the issue was 60 to 1 in favor of removal,[4] with the lone vote for retention coming from New Jersey deputy boxing commissioner Bob Lee.[11][20] The WBA cited concerns that as an imprisoned convict, Scott did not set a "good example", and that his opponents were disadvantaged because they had to come to the prison for all of his bouts. Sports Illustrated questioned whether those were the real motives for removing Scott from the rankings, given that the same conditions had applied when the WBA had started to rank him the year before. Scott speculated that the removal of his ranking had to do with the influence of Arum on the WBA, and that Arum offered a contract to Scott in 1979 but Muhammad convinced Scott not to accept it. Scott blamed Muhammad for not looking out for his best interest,[19] while Muhammad claimed that he had exclusive rights to Scott via an agreement with the Department of Corrections.[13] Without being ranked, Scott was not allowed to compete for a championship. Afterward, the WBA reinstated Galíndez as the light heavyweight champion.[4]

As a result of losing his ranking, Scott announced his retirement from boxing.[19][20][21] Nevertheless, Scott changed his mind shortly afterward and announced that he was "unretired" and would fulfill his contracts.[13][22][23] His next fight was against Jerry Celestine, whom he defeated by decision and claimed he was not trying to score a knockout to preserve his hand for a fight with López.[24] Like Scott, Celestine had boxed as a prison inmate in Louisiana on the undercard of Leon Spinks vs. Muhammad Ali II.[3] After the fight, Scott spelled out his issues with Muhammad and discussed working with his lawyer for permission to fight outside Rahway.[24] Muhammad expressed support for Scott and a desire to continue to help him, as well as optimism that the WBA decision to strip his ranking would be overturned.[21] Scott earned $7000 for the fight.[5][6]

Although Scott was no longer ranked, López wanted to proceed to fight Scott on the basis of earning a payday. He was slated to earn $40,000 for fighting Scott, with Scott earning $20,000.[25] The next month after the Celestine fight, Scott fought López, and defeated him by decision in a fight broadcast on NBC. No knockdowns occurred in the bout, but Scott cut López open as early as the first round. After the match, Scott declared that he should be the number 1 contender and called out new WBA light heavyweight champion Marvin Johnson and WBC heavyweight champion Larry Holmes. López stated that he wanted a rematch.[18] Boxing publication The Ring named Scott their world light heavyweight champion after the match.[26]

Murder conviction and later career

edit"He had a great run. He proved he was one of the best light heavyweights in the world, but once that chance of him fighting for a world title was virtually zero, there was no reason for people to pay attention. Then it was much easier to just view him as every other inmate in a maximum security prison, which means forgetting him."

In January 1980, Scott lost an appeal to have his armed robbery conviction thrown out. His argument centered around a voluntary statement that he gave but refused to sign, as well as the searching of his car without a search warrant. A three judge appeals panel disagreed, stating the unsigned statement was still legal evidence and a search warrant was not necessary for his car.[26]

On May 25, 1980, five and a half months after the López fight,[4] Scott had his first professional loss, an upset in which he was defeated by Jerry "The Bull" Martin.[27][28] Scott was knocked down twice by Martin, once in the first round and again late in the second round. He was defeated by decision. Scott was paid $40,000 for the fight, of which 10% was donated to a crime victims' fund.[12][27] Scott also held an escrow account with some of his winnings at this time, which he hoped to use to open a rehabilitation center for former prisoners, to be run by former prisoners.[12] A prison guard told Family Weekly in 1980 that Scott was a changed man because of his passion for boxing.[12]

In 1981, a judge ordered Scott to stand trial again for the murder of Everett Russ.[29] At this second trial, the prosecutor presented a slightly different version of events, attesting that Scott went into the building alone, robbed Barrett and assaulted Skinner before shooting Russ, who was expecting to receive drugs as well.[10] The prosecutor's alleged motive for the murder was that Scott did not like the kind of person Russ was as someone involved with the drug trade, and that Scott did not want Russ to tell police about the robbery. Scott's attorney, William Kunstler, admitted that Scott was guilty of the robbery but challenged the state's case for the murder.[30] Scott was found guilty that February,[10] and was sentenced to life in prison on March 20, 1981.[4] Scott continued to maintain his innocence, insisting he was appealing the verdict and would continue to pursue the light heavyweight championship,[11] though the loss to Martin and subsequent conviction for murder marked the functional end of Scott's consideration as a serious contender.[4]

In August, Scott defeated Dave Lee Royster, who had fought Scott to a draw in 1974.[31] Scott's last professional fight was on September 5, 1981, when he lost a unanimous decision to Dwight Braxton.[32] Braxton had formerly been an inmate at Rahway State Prison,[33] serving five and a half years for armed robbery. He knew Scott from time together at both Rahway and Trenton State Prisons, and was a part of the boxing program at Rahway.[34] Scott finished his boxing career with a record of 19 wins, 2 losses and 1 draw.[35]

Later life, death, and legacy

edit"Imagine if he didn't get in trouble. If somebody took him when he was a teenager, when he was going the wrong way, show him the right way, James Scott would be a household name today. And everybody would know him."

In 1984, Scott was transferred back to Trenton State Prison, and later to South Woods State Prison.[4] After he was no longer fighting, Scott gave few interviews. He mentioned to one reporter decades after the end of his career that he was no longer a popular figure in prison, and expressed that he felt he should no longer be incarcerated.[4]

Scott was released from prison on parole in 2005 after serving 28 years.[11][36] His parole officer, trying to find a way to fill Scott's time, took Scott to a boxing gym with a youth program. There, Scott worked with children on training and gave tips on boxing to them. He would also travel to watch their matches around the state.[11] On November 8, 2012, Scott was inducted in the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame. President of the Hall of Fame, Henry Hascup, stated that Scott's boxing alone would have qualified him for the Hall of Fame much earlier, but his questionable past made entry difficult. Hascup was swayed to make it happen after speaking with the trainers and children from the boxing gym.[11] In his final years, Scott suffered from dementia and at the end of his life lived in a New Jersey nursing home.[4] He died on May 8, 2018, at the age of 70.[1]

According to Hascup, Scott would have been a household name in boxing had he not been in trouble most of his life.[11] Brin-Jonathan Butler and Kurt Emhoff of SB Nation expressed the complexities of Scott's legacy by comparing his crime with his boxing, stating, "If a boxer achieves anything approaching artistry in his craft, we must accept that his finest works are canvasses stained with human blood. Yet before James Scott offered up his masterpiece against Eddie Gregory in the ring, he also spilled the blood of a dead man, Everett Russ, inside his car."[4] Boxing journalist Bernard Fernandez compared Scott to Tony Ayala Jr. and Ike Ibeabuchi as talented boxers who could have achieved more had they properly reformed after past offenses, similar to Eddie Gregory, Dwight Braxton, and Bernard Hopkins.[9] Murad Muhammad remembered Scott as "a promoter's dream. Very articulate. Very intelligent. And when we talked boxing, you'd have thought you were talking to Muhammad Ali." Boxing analyst Steve Farhood has expressed doubt that Scott's story could happen in the modern day. "I don't think people would be as lenient and as understanding," he said. "For that matter, I think without the willpower James Scott had maybe none of this would have ever happened, maybe it never would have been launched in the first place. To think of how far this guy took this mission given his circumstances was amazing. It throws stereotypes out the window and it's a lesson I think in understanding the kind of man that is behind bars. You just can't generalize."[11]

Professional boxing record

edit| 22 fights | 19 wins | 2 losses |

|---|---|---|

| By knockout | 10 | 0 |

| By decision | 9 | 2 |

| Draws | 1 | |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round (scheduled), time | Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Loss | 19–2–1 | Dwight Braxton | UD | 10 | September 5, 1981 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 21 | Win | 19–1–1 | Dave Lee Royster | TKO | 7 (10), 0:52 | August 10, 1981 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 20 | Loss | 18–1–1 | Jerry Martin | UD | 10 | May 25, 1980 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 19 | Win | 18–0–1 | Yaqui López | UD | 10 | December 1, 1979 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 18 | Win | 17–0–1 | Jerry Celestine | UD | 10 | October 27, 1979 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 17 | Win | 16–0–1 | Ennio Cometti | RTD | 5 (10), 3:00 | August 26, 1979 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 16 | Win | 15–0–1 | Bunny Johnson | RTD | 7 (10), 3:00 | July 1, 1979 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 15 | Win | 14–0–1 | Richie Kates | TKO | 10 (10), 1:32 | March 10, 1979 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 14 | Win | 13–0–1 | Eddie Gregory | UD | 12 | October 12, 1978 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 13 | Win | 12–0–1 | Fred Brown | TKO | 4 (10) | September 9, 1978 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 12 | Win | 11–0–1 | Diego Roberson | KO | 2 (8) | May 24, 1978 | Rahway State Prison, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, US |

| 11 | Win | 10–0–1 | Jesse Burnett | MD | 10 | February 25, 1975 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 10 | Win | 9–0–1 | Raul Arturo Loyola | UD | 10 | November 19, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 9 | Draw | 8–0–1 | Dave Lee Royster | MD | 10 | September 10, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 8 | Win | 8–0 | Bobby Lloyd | UD | 10 | July 9, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 7 | Win | 7–0 | Koli Vailea | KO | 5 (10), 2:43 | May 14, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 6 | Win | 6–0 | Ray Anderson | UD | 10 | April 23, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 5 | Win | 5–0 | Frank Evans | UD | 10 | April 2, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 4 | Win | 4–0 | Kirkland Rolle | TKO | 8 (10), 2:15 | March 5, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 3 | Win | 3–0 | Willie Johnson | TKO | 4 (8) | February 19, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 2 | Win | 2–0 | Hydra Lacy | KO | 3 (6) | February 5, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

| 1 | Win | 1–0 | John L. Johnson | UD | 6 | January 22, 1974 | Auditorium, Miami Beach, Florida, US |

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "JAMES SCOTT Jr". The Star-Ledger. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ a b "James Scott". New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame. November 8, 2012. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Rein, Richard K. (December 11, 1978). "In This Corner, the One with Bars, Is Possibly the Best Light Heavyweight in the World". People. Vol. 10, no. 24. p. 134. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Butler, Brin-Jonathan; Emhoff, Kurt (March 12, 2014). "Gold in the Mud - The Twisted Saga of Jailhouse Boxer James Scott's Battle for Redemption". SB Nation. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Anderson, Dave (February 1, 1979). "'Gold in the Mud' for 57735". The New York Times. pp. B5. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Dave (February 10, 1979). "He's Gold in the Mud". Winchester Evening Star. Winchester, Virginia. p. 15. Retrieved November 5, 2024 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Putnam, Pat (October 23, 1978). "Slambang Win In The Slammer". Sports Illustrated. pp. 76, 81. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Schenerman, Beth (December 17, 1978). "Inmate Sets Sights on Boxing Title". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Fernandez, Bernard (May 14, 2018). "James Scott, Once a Famous Prison Boxer, Died Free but Virtually Anonymous". The Sweet Science. Archived from the original on July 22, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Scott is Found Guilty of Murder, Faces Life". The New York Times. February 5, 1981. pp. B-7. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Mambo, Andrew (July 25, 2017). "The Fighter Inside". 30 for 30 Podcasts (Podcast). ESPN. Archived from the original on March 25, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Gallanter, Marty (November 9, 1980). "James Scott's Fight for Freedom". Family Weekly. p. 17. Retrieved November 5, 2024 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ a b c d Schenerman, Beth (October 21, 1979). "Infighting Over Scott". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Katz, Michael (March 11, 1979). "Scott, Prisoner, is Victorious". The New York Times. pp. S9. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "Scott Knocks Out Johnson in Rahway Bout". The New York Times. July 2, 1979. pp. C5. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Corrigan, Ed (August 27, 1979). "Scott Stops Cometti, Remains Undefeated". The New York Times. pp. C2. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Benagh, Jim (May 25, 1981). "Sports World Specials". The New York Times. p. C2. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ a b Cady, Steve (December 2, 1979). "Scott Gains Decision And Stays Unbeaten; 'I Should Be No. 1'". The New York Times. pp. S3. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Scorecard". Sports Illustrated. Vol. 51, no. 16. October 15, 1979. p. 26. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ a b c Yannis, Alex (October 4, 1979). "Scott Loses Rating, Quits Ring". The New York Times. pp. D16. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Corrigan, Ed (November 25, 1979). "Scott Faces Crucial Prison Bout". The New York Times. pp. S7. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Scott to fight again". Wilmington Morning Star. October 10, 1979. p. 5–B. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ "Scott Decides to "Unretire"". The New York Times. October 10, 1979. pp. B6. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "Scott Outpoints Celestine in Fight at Prison". The New York Times. October 28, 1979. pp. S11. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "James Scott Takes On Lopez". Bluefield Daily Telegraph. Bluefield, West Virginia. December 1, 1979. p. 8. Retrieved November 5, 2024 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ a b "Judge refuses plea by James Scott". Twin Falls Times News. January 15, 1980. p. C-3. Retrieved November 5, 2024 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ a b Richman, Milton (May 27, 1980). "Scott straddles ring and cellblock". The Bulletin. Bend, Ore. UPI. p. 17. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Harvin, Al (May 26, 1980). "Scott is Floored in First Defeat". The New York Times. pp. S2. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ "Boxer Scott Ordered to be Tried Jan. 26". The New York Times. January 12, 1981. pp. C9. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "Scott's murder trial". Playground Daily News. Fort Walton Beach, Florida. January 28, 1981. p. 9A. Retrieved November 5, 2024 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ McGowen, Dean (August 11, 1981). "Scott stops Royster in seventh round". The New York Times. pp. C12. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "Braxton Outpoints Scott in Prison Bout". The New York Times. September 6, 1981. pp. 5–11. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Bonapace, Ruth (September 6, 1981). "Scott ring comeback a real flop". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. p. C1. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Katz, Michael (September 3, 1981). "Braxton vs. Scott: A Rahway Grudge". The New York Times. pp. D20. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "BoxRec: James Scott". BoxRec. Archived from the original on March 21, 2024. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ McIlvanney, Hugh (February 20, 2005). "Verbal bout with a cell block champ". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ "Fighter profile: James Scott". FightFax. Archived from the original on November 10, 2024. Retrieved November 10, 2024.