Jacopo Aconcio (c. 1520 – c. 1566) was an Italian jurist, theologian, philosopher and engineer. He is now known for his contribution to the history of religious toleration.[1][2]

Jacopo Aconcio | |

|---|---|

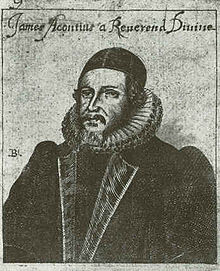

Jacopo Aconcio, c. 1560 |

Life

editAconcio was born around 1520 in Trento, Italy, or possibly the nearby town of Ossana.[3] He was the son of Gerolamo Aconcio and his wife, Oliana. He studied law and later became a notary in 1548 when he was admitted to the Collegio dei Notai of Trento.[4] In 1549 he entered the service of Count Francesco Landriano, a courtier serving the emperor, Charles V in Vienna. Aconcio remained with Landriano for seven years and then around 1556 became secretary to Cardinal Madruzzo, the imperial governor in Milan.[4]

Aconcio later wrote that he became attracted to the ideas of the Reformation while in service to Landriano. He knew that it was dangerous to express these beliefs openly while living in Italy and decided to pursue a career in military engineering that would allow him to live safely in exile. He taught himself the basics of engineering through conversations with military men like Landriano and Giovanni Maria Olgiati. He also took careful note of fortifications he had the opportunity to visit while travelling through Europe.[4]

When conservative Paul IV became pope in 1555, he instituted a rigorous campaign to suppress heresy in the Italian States. Aconcio felt threatened and in June 1557 he renounced his Catholic faith and fled first to Basel and then on to Zürich.[5] In Basel he met Bernardino Ochino and other radical Italian reformers. In Switzerland he wrote his first works, Dialogue di Silvio e Mutio, outlining the Lutheran criticisms of the Catholic church and Summa de Christiana religione, which presents a view of religion purged of the controversial points that divided Christendom. Both were published in 1558.[3] At the same time he published a secular work, De Methodo, hoc est, de recte investigandarum tradendarumque Scientiarum ratione, which lays out an approach to intellectual inquiry that emphasizes a rational, almost mathematical approach, proceeding from clear and concrete first principles.[4]

While in Switzerland, Aconcio became acquainted with some of the Marian exiles, English Protestants who had fled persecution under the reign of Queen Mary. In 1558 Aconcio moved to Strasbourg and then contemplated a move to England where he hoped for favourable treatment of Protestants under the new ruler, Queen Elizabeth. In addition, Sir William Cecil, England's secretary of state, was recruiting Italian engineering expertise to improve English fortifications and in September 1559 Aconcio was brought to England by the new government.[3][4]

In December 1559 he petitioned the queen for grants of patent on a variety of machines powered by water wheels. This was the first patent request in England but it was not granted to Aconcio until 1565. In 1560 he was granted an annual royal pension of 60 pounds and in 1561 he became an English subject. In 1563 Aconcio proposed a plan to drain two thousand acres of marshland along the south bank of the Thames between Erith and Plumstead. The effort was initially successful, but bad weather flooded what he had managed to reclaim, and Aconcio was obliged to hand over control of the project to his partner, Giovanni Battista Castiglione, and other investors.[4] It was not until 1564 that he was hired as a military engineer to participate in a joint review of the fortifications being developed at Berwick Castle, one of the most important strongholds along the Scottish-English border. The work being done by engineer Richard Lee had been criticized by the government's chief Italian expert, Giovanni Portinari, and Aconcio was sent to Berwick to provide another perspective. He made his own design suggestions, some of which were implemented.[3]

On his arrival in London, he joined the Dutch Reformed Church in Austin Friars, but he was "infected with Anabaptistical and Arian opinions" and was excluded from the sacrament by Edmund Grindal, bishop of London.[6]

Works

editBefore reaching England he had published a treatise on the methods of investigation, De Methodo, hoc est, de recte investigandarum tradendarumque Scientiarum ratione (Basel, 1558, 8vo); and his critical spirit placed him outside all the recognized religious societies of his time. His heterodoxy is revealed in his Stratagematum Satanae libri octo, sometimes abbreviated as Stratagemata Satanae,[7] published in 1565 and translated into various languages. The Stratagems of Satan are the dogmatic creeds which rent the Christian church. Aconcio sought to find the common denominator of the various creeds; this was essential doctrine, and the rest was immaterial. To arrive at this common basis, he had to reduce dogma to a low level, and his result was generally repudiated.[2] Stratagemata Satanae was not translated into English until 1647, but afterwards, it became very influential among English liberal theologians.[8]

John Selden applied to Aconcio the remark ubi bene, nil melius; ubi male, nemo pejus ("Where good, none better. Where bad, none worse").[citation needed] The dedication of such a work to Queen Elizabeth illustrates the tolerance or religious laxity during the early years of her reign. Aconcio later found another patron in Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, and died about 1566.[2]

Publications

edit- Stratagematum Satanae libri octo (1565)

- De methodo sive recta investigandarum tradendariumque artium ac scientarum ratione libellus, (1558) (modern edition: De methodo e opuscoli religiosi e filosofici, edited by Giorgio Radetti, Firenze: Vallecchi, 1944)

- Somma brevissima della dottrina cristiana

- Una esortazione al timor di Dio

- Delle osservazioni et avvertimenti che haver si debbono nel legger delle historie

- English translation, Darkness Discovered (Satans Stratagems), London, 1651 (facsimile ed.,1978 Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, ISBN 978-0-8201-1313-5).[2]

- Trattato Sulle Fortificazioni, edited by Paola Giacomoni, Giovanni Maria Fara, Renato Giacomelli, and Omar Khalaf (Firenze: L.S. Olschki, 2011). ISBN 978-8-8222-6068-0

References

edit- ^ Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ISBN 0-550-18022-2, page 6

- ^ a b c d Pollard 1911.

- ^ a b c d Keller, 2004

- ^ a b c d e f White, 1967

- ^ O'Malley, 1945

- ^ Pollard, 1911: Cal. Slate Papers, Dom. Ser., Addenda, 1547-1566, p. 495.

- ^ NB for Latin grammar, dropping the two last words justifies the dropping of the genitive.

- ^ Kamen, Henry (1996). "Acontius, Jacobus". In Hans J. Hillerbrand (ed.). Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0195064933.

Attribution::

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Pollard, Albert Frederick (1911). "Aconcio, Giacomo". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 151.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1885). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Further reading

edit- Keller, A. G. (2004). "Aconcio, Jacopo [Jacobus Acontius]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- O'Malley, Charles Donald (1945). Jacopo Acontio: His Life, Thought and Influence (PhD). Leland Stanford Junior University.

- White, Lynn (1967). "Jacopo Aconcio as an Engineer". The American Historical Review. 72 (2): 425–444. doi:10.2307/1859235. JSTOR 1859235.

External links

edit- Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie - online version at Wikisource

- Works by Jacopo Aconcio at Post-Reformation Digital Library