Isabella Kirkland (born 1954) is an American visual artist and biodiversity researcher.[1][2] She is known for intricate, representational paintings that straddle art history, natural science and ecological activism.[3][4][5] Since the mid-1990s, she has documented biota in series focused on species that are extinct, disappearing, collected or illegally trafficked, or emerging from near-extinction.[6][7][8] Her work fuses the classical naturalist tradition of wildlife painters like John James Audubon and the precise rendering style and time-tested oil techniques of 17th-century Dutch Master still life painters.[9][10][11] Situated in the contemporary context of global warming, however, her paintings subtly upend such idealized traditions, invoking a sense of accountability in response to the specter of ecological flux and impermanence.[12][13][14] New York Times critic Ken Johnson wrote that Kirkland "produces richly atmospheric pictures collectively populated by hundreds of animals. … Updating the peaceable kingdom genre, she is trying to make beautiful paintings of the world at its most beautiful, not for the sake of art but for the sake of our endangered biosphere. She does not preach but communicates an infectious spirit of care."[1]

Isabella Kirkland | |

|---|---|

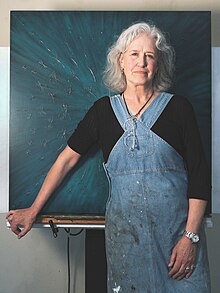

Isabella Kirkland in 2023 | |

| Born | 1954 Old Lyme, Connecticut, United States |

| Education | San Francisco Art Institute |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, ecological activism |

| Style | Naturalism |

| Spouse | Chris Tellis |

| Awards | Wynn Newhouse Award |

| Website | Isabella Kirkland |

Kirkland's work belongs to the collections of institutions including the Whitney Museum,[15] Berkeley Art Museum[12] and Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM).[16] She has exhibited at the National Academy of Sciences,[2] Harvard Museum of Natural History,[11] Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago)[5] and SLAM, among other venues.[6] She is a research associate in aquatic biology at the California Academy of Sciences[2][17] and has spoken about ecological issues at conferences including several TED events.[18][19]

Biography

editKirkland was born in 1954 in Old Lyme, Connecticut.[20] She attended Guildford College in North Carolina and Virginia Commonwealth University, before studying sculpture at the San Francisco Art Institute in the late 1970s.[17][10]

Kirkland lived in New York City through much of the 1980s, pursuing her art career while also becoming a licensed taxidermist and teaching herself botanical illustration, both of which presaged her turn to naturalistic painting in the 1990s.[21][8][10] Her early art centered on environments hovering between painting and sculpture and impermanent conceptual installations that used unusual materials (e.g., ice, trash) and examined contemporary social issues.[22][21][17] She presented this work in solo exhibitions at Gallery Paule Anglim, New Langton Arts (both in San Francisco) and Real Art Ways (Hartford) and group shows at The Alternative Museum (New York), Hallwalls (Buffalo) and The Living Room (San Francisco), among other venues.[22][23][24][25] New York Times critic Vivien Raynor wrote of the Real Art Ways exhibition, which addressed overpopulation, nuclear war and racism: "Seemingly reluctant to bully her viewers, Kirkland errs on the side of tortuousness and sometimes, of playfulness, but her integrity is unmistakable."[24][26]

In 2004, Kirkland suffered neural and motor control damage from parasitic infection after a tropical roundworm attacked part of her spinal cord. The incident and its effects—so rare that doctors were unaware of the symptoms or treatments—left her unable to draw for several months.[27][28] She eventually recovered full control of her right hand, but was left with chronic neuropathic pain in the upper right quadrant of her body, most critically, dysesthesia (sometimes described as a burning sensation under the skin) in her hand and wrist; she has stated that the condition can abate during the flow-state induced by painting.[28] In 2008, Kirkland received the Wynn Newhouse Award, which recognizes contributions of artists with disabilities to contemporary art.[28]

Since 2000, Kirkland has had solo exhibitions at Feature Inc. (New York),[1][29] the National Academy of Sciences,[2] Toledo Art Museum,[8] Saint Louis Art Museum,[6] Dayton Art Institute[30][13] and Hosfelt Gallery (San Francisco), among others.[10] She has shown in nature-related surveys at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art,[31] Tucson Museum of Art[32] and Whatcom Museum.[33]

Kirkland lives in Sausalito, California with her husband, Chris Tellis, on a yellow ferryboat docked in the San Francisco Bay.[34][9][17][35]

Naturalistic painting

editIn the 1990s, Kirkland's early artistic focus on impermanence shifted to a consideration of art's lasting power;[21] the change was cemented by a museum exhibition of Dutch Master works, which convinced her to learn to paint in that style.[17][10] Her initial foray was the "Nature in the Margins" series (1995–99), consisting of realistic paintings of individual, rare animals living in human environments that raised questions about wildlife survival amid overdevelopment.[21] In 1999, a Sierra Club list of the 100 most-endangered animals in the U.S. crystallized parallel themes in her work—the durability of art and naturalist painting—into a single concept and her first mature series: the "Taxa" works, which catalogued various species groups.[21][17][36]

Kirkland's naturalist paintings are characteristically large, lush works composed like well-balanced tapestries that both celebrate decorative beauty and address environmental degradation and homogenization.[37][13] She meticulously depicts species that do not necessarily belong together, generally at scale.[2][5][3][17] Her concentrated level of detail and complex compositions function to slow down the viewing process and encourage deeper connection—and potentially—a sense of responsibility.[2] American Scientist writer Anna Lena Phillips noted, "perhaps paradoxically, by removing species from their habitats, the paintings acquire the power to change our perception of the plants and animals within them. In this sense, Kirkland's work moves beyond the representation of scientific ideas to offer new ways of thinking about the organisms she depicts."[2] Kirkland carefully researches the species in the paintings—which can take more than a year to execute—using original scientific descriptions, specimens, rubrics and databases often made available to viewers through keys or explanatory texts.[5][2][3][1]

Writers such as Renny Pritikin place Kirkland among a generation of artists reclaiming traditional realist painting and "moving it toward extra-aesthetic ends" and complex, contemporary concepts.[10][35][4] She applies the accurate depiction of flora and fauna once used in scientific illustration to different means, regarding her intentionally durable oil paintings as a hedge against a possibly dystopian future—"alarm clocks" or analog "time capsules" of biodiversity that may outlast both the species depicted and the ephemerality of digital records.[5][31][3][19] In this sense, like Dutch Master still lifes or history and political paintings (e.g., Guernica ), they serve the functions of bearing witness and carrying cultural or metaphorical content.[5][31][36][9]

Painting series, 1999–ongoing

editThe six large imaginary landscapes of Kirkland's "Taxa" suite (1999–2004) represent dynamic change in the natural world caused by human agency through depictions of nearly 400 life-size species.[9][35][6][30] New York Times writer Andrew C. Revkin described them as "a mix of Dutch Master and "Where's Waldo?" … full of hidden things worth looking for."[11] Descendant (1999) portrayed 61 endangered or extinct species in the mainland U.S., Hawaii and Central America, while Ascendant (2000) depicted non-native species that are crowding out native residents in the U.S.[2][17][36] In Trade (2001) and Collection (2002), vivid tableaux of depleted species that are highly valued (and thus harvested, poached and sold) underscored the human desire to possess exotic creatures.[2][11] Back (2003) presented 48 species thought to be extinct but brought back into existence, using warm natural tones to convey the resilience of life;[11][5] in contrast, the darker Gone (2004) catalogued 63 organisms that underwent full-species, worldwide extinction, many due to the colonization of the New World.[21][2]

The four paintings of the "Nova" suite (2007–11; exhibited at Feature, Inc. in 2011) explored the complexity and interdependency of life through depictions of 250 newly discovered plant and animals.[1][8] The profusely detailed, metaphoric ecosystems each represent a strata of a typical tropical rainforest: Forest Floor, Understory, Canopy and Emergent (the treetop level).[1] Forest Floor (2007) included a stream with fish and salamander beneath its surface and multiple species of birds, insects and animals; Canopy (2008) featured spongy mats of moss, hornworts, liverworts and orchids, a beetle in flight and a heavy-jawed, yet-to-be-named mouse, among other species.[8] The New York Times likened the work to "lush, naturalist illustration with roots in the 19th-century transcendentalist realism of Martin Johnson Heade."[1]

In later series, Kirkland turned to subjects including aquatic life (e.g., Squat Lobsters, 2021), gravestone lichens, butterflies and birds, phasmid (walking sticks and leaf insects) eggs, and flora.[17][10][38] Her show "Nudibranchia: Butterflies of the Sea" (Bolinas Museum, 2014) explored those wildly colorful, soft-bodied marine gastropod mollusks in works that included a large canvas arraying 206 of the creatures life-size in rows from smallest (at top) to largest.[17][10][7] "The Small Matter" (Hosfelt, 2021) was a near-retrospective scale show portraying a range of organisms, many invisible to the naked eye.[10][4] It included depictions of specimens unnaturally bunched side-by-side, pinned or tagged, such as Bachman's Warblers Redux (2018) and the butterfly Pseudacraea boisduvali (2020), which suggested a wry meta-commentary on the human need to impose taxonomical order onto nature.[10][4]

Writing and other professional activities

editKirkland has been a featured speaker at numerous biodiversity and ecological conferences and events,[39] including TEDx DeExtinction (2013),[40] The Long Now Foundation (2016)[41][7] and the TED Countdown Summit 2023.[18] She exhibited work at TED 2007.[19] In addition to serving as a research associate in aquatic biology and scientific illustrator at the California Academy of Sciences,[17][42] she is an artist partner of Art To Acres, an organization supporting large-scale global land and animal conservation through art and financial donations.[43][5]

Collections and recognition

editKirkland's work belongs to the public art collections of the Bates College Museum of Art,[44] Berkeley Art Museum,[12] Chazen Museum of Art,[45] Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center,[46] Hammer Museum, Hood Museum of Art,[47] Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,[48] Queens Museum, RISD Museum,[49] Saint Louis Art Museum of Art,[16] San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Toledo Art Museum,[50] Whitney Museum,[15] Yale University Art Gallery,[51] and Zimmerli Art Museum,[52] among others.

Her paintings have been reproduced as illustrations for several books and publications and as cover art for Whole Earth magazine[53] and the books The Future of Life (2002) by E. O. Wilson, Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death, and Generations (2017, by Rose, van Dooren and Chrulew), and Animal Traffic: Lively Capital in the Global Exotic Pet Trade (2020) by Rosemary-Claire Collard.[54][11][55][56]

Kirkland has been recognized with a Wynn Newhouse Award (2008) and grants from George Sugarman Foundation (2005) and Marin Arts Council (2004).[28]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Johnson, Ken. "Isabella Kirkland," The New York Times, June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Phillips, Anna Lena. "Ars Scientifica," American Scientist, May-June 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Revkin, Andrew C. "Permanent Art, Evanescent Life," The New York Times, November 1, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Roth David M. "The Nature Conundrum," SquareCylinder, June 2, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Baker, Kamrin. "Artist Advocates For Endangered & Extinct Species Through Paintings," Good Good Good, July 14, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Weir, Alex. "Life in its Fleeting Glory," Riverfront Times, January 23, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Garchik, Leah. "Isabella Kirkland and the glories of the shell-less mollusk," San Francisco Chronicle, March 29, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Pollick, Steve. "250 new plants, animals at Art Museum," Toledo Blade, September 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Bonetti, David. "Three artists who grapple with history," San Francisco Examiner, November 20, 2001. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pritikin, Renny. "Renny Pritikin on Isabella Kirkland @ Hosfelt," SquareCylinder, May 10, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Revkin, Andrew C. "Paintings of Nature's Comeback Kids," The New York Times, October 30, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Isabella Kirkland, Artist. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Dayton Art Institute. "Dayton Art Institute opens Isabella Kirkland: Stilled Life," February 24, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Art in Embassies, U.S. Department of State. Isabella Kirkland, Personnel. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Whitney Museum of American Art. Isabella Kirkland, Canopy, Collection. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Saint Louis Art Museum. Isabella Kirkland, Collection. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Larson, Vicki. "Isabella Kirkland paints disappearing species—and newfound ones—with scientific detail," Marin Independent Journal, October 15, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b TED. "Isabella Kirkland: The Beauty of Wildlife," Talks, July 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c TED. "Isabella Kirkland," Speakers. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Isabella Kirkland, Project. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Ames, Michael. "Going, going, almost gone," Idaho Mountain Express, February 15, 2006.

- ^ a b Atkins, Robert. "Katherine Sherwood and Isabella Kirkland," The San Francisco Bay Guardian, September 25, 1980, p. 19–20.

- ^ Reveaux, Anthony. "Looking at Contemporary Life," Artweek, 1984.

- ^ a b Raynor, Vivien. "Past and Present Futurists," The New York Times, May 29, 1983. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Hallwalls. Isabella Kirkland, Artists. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Goldberg, Carole. Review, Hartford Advocate, May 4, 1983.

- ^ Colliver, Victoria. "Home DNA tests create medical, ethical quandaries," San Francisco Examiner, August 21, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Wynn Newhouse Awards. Isabella Kirkland. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Feature, Inc. Isabella Kirkland, Nova, 2011, Exhibitions. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Kamholtz, Jonathan. "Death and Taxa: Isabella Kirkland: Stilled Life," AEQAI, April 26, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ a b c Nilsen, Richard. "How Real Can It Get? Perceptions Always in Flux," The Arizona Republic, May 30, 2004.

- ^ Tucson Museum of Art. Trouble in Paradise: Examining Discord in Nature and Society. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Whatcom Museum. "Thought-Provoking Exhibition to Explore Endangered Species and Biodiversity," 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Surtees, Joshua. "If you're going to San Francisco – stay on a stylish Sausalito houseboat," The Guardian, June 28, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Tropiano, Dolores. "Natural wonder show," Scottsdale Republic, September 2004.

- ^ a b c Bossick, Karen. "'Gone,' 'Back,' and 'Nova,'" The Wood River Journal, February 15, 2006.

- ^ Eclectix. "Isabella Kirkland, Eclectix Interview 47," September 19, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Wisnieski, Adam. "A garden variety of art at Wave Hill," The Riverdale News, April 11, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Garchik, Leah. "How to choose words, get money and stay connected," San Francisco Chronicle, October 18, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Revive & Restore. "TEDx DeExtinction," Speakers. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Long Now Foundation. "Painting the Endangered World | Isabella Kirkland", 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Dumbacher, Jack. "Wind, Sand and Starlings at Yanaba Island," The New York Times, October 25, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Art to Acres. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Bates Museum of Art. Isabella Kirkland, Artists. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Chazen Museum of Art. Canopy, Isabella Kirkland, Collection. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center. Isabella Kirkland, Canopy, Objects. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Hood Museum of Art. Isabella Kirkland, Gone, Objects. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Isabella Kirkland, Artist. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ RISD Museum. Isabella Kirkland, Canopy, Collection. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Toledo Museum of Art. Taxa, Isabella Kirkland, Objects. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Yale University Art Gallery. Canopy, Isabella Kirkland, Collections. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Zimmerli Art Museum. Canopy, Isabella Kirkland, Objects. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ San Francisco Art Institute. "Whole Earth 50th Anniversary Exhibition," Exhibit. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Wilson, E. O. The Future of Life, New York: Knopf, 2002. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Rose, Deborah Bird and Thom Van Dooren, Matthew Chrulew (eds). Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death, and Generations, New York: Columbia University Press, 2017. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Collard, Rosemary-Claire. Animal Traffic: Lively Capital in the Global Exotic Pet Trade, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

External links

edit- Isabella Kirkland official website

- "Isabella Kirkland: The Beauty of Wildlife," TED Talk, July 2023

- "Painting the Endangered World | Isabella Kirkland", talk at Long Now Foundation, 2017

- "Isabella Kirkland: Material Longevity", Berkeley Arts + Design, 2020

- Isabella Kirkland, Eclectix interview, 2013

- Isabella Kirkland, Hosfelt Gallery.

- Isabella Kirkland, Feature, Inc.