An iron planet is a type of planet that consists primarily of an iron-rich core with little or no mantle. Mercury is the largest celestial body of this type in the Solar System (as the other terrestrial planets are silicate planets), but larger iron-rich exoplanets are called super-Mercuries.

Iron is the sixth most abundant element in the universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, oxygen, carbon, and neon.

Origin

editIron-rich planets may be the remnants of normal metal/silicate rocky planets whose rocky mantles were stripped away by giant impacts. Some are thought to consist of diamond fields. Current planet formation models predict iron-rich planets will form in close-in orbits or orbiting massive stars where the protoplanetary disk presumably consists of iron-rich material.[1]

Characteristics

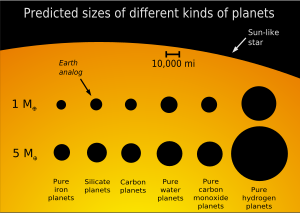

editIron-rich planets are smaller and denser than other types of planets of comparable mass.[2] Such planets would have no plate tectonics or strong magnetic field as they cool rapidly after formation. These planets are not like Earth.[1] Since water and iron are unstable over geological timescales, wet iron planets in the goldilocks zone may be covered by lakes of iron carbonyl and other exotic volatiles rather than water.[3]

In science fiction, such a planet has been called a "Cannonball".[4]

Candidates

editAn extrasolar planet candidate that may be composed mainly of iron is Kepler-974b.[5]

A super-Mercury candidate is GJ 367b.[6]

The star HD 23472 is orbited by two super-Mercuries.[7]

HD 137496 b is a dense hot super-Mercury.[8]

LHS 3844 b is potentially an Fe-rich super-Mercury.[9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Characteristics of Terrestrial Planets" by John Chambers, from "The Great Planet Debate: Science as Process", August 14–16, 2008, The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Kossiakoff Center, Laurel, MD. http://gpd.jhuapl.edu/abstracts/abstractFiles/chambers_abstract.pdf Archived 2011-08-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "All Planets Possible - Astrobiology Magazine". astrobio.net. 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Big Planets: Super-Earths in Science Fiction" by Stephen Baxter, JBIS Vol 67, No 03 (March 2014), p.108

- ^ Gillett, Stephen L. (1996). Ben Bova (ed.). World-Building. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer's Digest Books. p. 173. ISBN 158297134X.

- ^ Rappaport, Saul; Sanchis-Ojeda, Roberto; Rogers, Leslie A.; Levine, Alan; Winn, Joshua N. (19 April 2018). "The Roche Limit for Close-orbiting Planets: Minimum Density, Composition Constraints, and Application to the 4.2 hr Planet KOI 1843.03". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 773 (1): L15. arXiv:1307.4080. Bibcode:2013ApJ...773L..15R. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/773/1/L15. S2CID 35253735. Retrieved 19 April 2018 – via Institute of Physics.

- ^ Goffo, Elisa; et al. (2023). "Company for the Ultra-high Density, Ultra-short Period Sub-Earth GJ 367 b: Discovery of Two Additional Low-mass Planets at 11.5 and 34 Days". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 955 (1): L3. arXiv:2307.09181. Bibcode:2023ApJ...955L...3G. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ace0c7.

- ^ Barros, S. C. C.; et al. (2022). "HD 23472: A multi-planetary system with three super-Earths and two potential super-Mercuries". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 665: A154. arXiv:2209.13345. Bibcode:2022A&A...665A.154B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202244293.

- ^ Azevedo Silva, T.; et al. (2022). "The HD 137496 system: A dense, hot super-Mercury and a cold Jupiter". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 657: A68. arXiv:2111.08764. Bibcode:2022A&A...657A..68A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202141520.

- ^ Kane, Stephen R.; Roettenbacher, Rachael M.; Unterborn, Cayman T.; Foley, Bradford J.; Hill, Michelle L. (2020). "A Volatile-poor Formation of LHS 3844b Based on Its Lack of Significant Atmosphere". The Planetary Science Journal. 1 (2): 36. arXiv:2007.14493. Bibcode:2020PSJ.....1...36K. doi:10.3847/PSJ/abaab5.