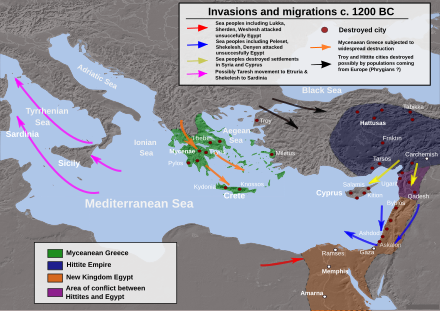

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a period of societal collapse in the Mediterranean basin during the 12th century BC. It is thought to have affected much of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East, in particular Egypt, Anatolia, the Aegean, eastern Libya, and the Balkans. The collapse was sudden, violent, and culturally disruptive for many Bronze Age civilizations, creating a sharp material decline for the region's previously existing powers.

The palace economy of Mycenaean Greece, the Aegean region, and Anatolia that characterized the Late Bronze Age disintegrated, transforming into the small isolated village cultures of the Greek Dark Ages, which lasted from c. 1100 to c. 750 BC, and were followed by the better-known Archaic Age. The Hittite Empire spanning Anatolia and the Levant collapsed, while states such as the Middle Assyrian Empire in Mesopotamia and the New Kingdom of Egypt survived in weakened forms. Other cultures such as the Phoenicians enjoyed increased autonomy and power with the waning military presence of Egypt and Assyria in West Asia.

Competing theories of the cause of the Late Bronze Age collapse have been proposed since the 19th century, with most involving the violent destruction of cities and towns. These include climate change, volcanic eruptions, droughts, disease, invasions by the Sea Peoples or migrations of the Dorians, economic disruptions due to increased ironworking, and changes in military technology and strategy that brought the decline of chariot warfare. Following the collapse, gradual changes in metallurgic technology led to the subsequent Iron Age across Europe, Asia, and Africa during the 1st millennium BC.

Scholarship in the late 20th and early 21st century has articulated views of the collapse as being more limited in scale and scope than previously thought.[1][2][3]

Overview

editThe German historian Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren first dated the Late Bronze Age collapse to 1200 BC. In an 1817 history of Ancient Greece, Heeren stated that the first period of Greek prehistory ended around this time, based on a dating of the fall of Troy to 1190 BC. In 1826, he dated the end of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt to around the same time. Additional events that have been dated to the first half of the 12th century BC include invasions by the Sea Peoples and Dorians, the fall of Mycenaean Greece and Kassites in Babylonia, and the carving of the Merneptah Stele—whose inscription included the earliest attested mention of Israel in the southern Levant[4][5]—as well as the destruction of Ugarit and the Amorite states in the Levant, the fragmentation of the Luwian states of western Anatolia, and a period of chaos in Canaan.[6] The deterioration of these governments interrupted trade routes and led to severely reduced literacy in much of this area.[7]

Debate

editInitially historians believed that in the first phase of this period, almost every city between Pylos and Gaza was violently destroyed, and many were abandoned, including Hattusa, Mycenae, and Ugarit, with Robert Drews claiming that, "Within a period of forty to fifty years at the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the twelfth century, almost every significant city in the eastern Mediterranean world was destroyed, many of them never to be occupied again."[8]

However more recent research has shown that Drews overestimated the number of cities that were destroyed and referenced destructions that never happened. According to Millek,

If one goes through archaeological literature from the past 150 years, there are 148 sites with 153 destruction events ascribed to the end of the Late Bronze Age ca. 1200 BC. However, of these, 94, or 61%, have either been misdated, assumed based on little evidence, or simply never happened at all. For Drews's map, and his subsequent discussion of some other sites which he believed were destroyed ca. 1200 BC, of the 60 "destructions" 31, or 52%, are false destructions. The complete list of false destructions includes other notable sites such as: Lefkandi, Orchomenos, Athens, Knossos, Alassa, Carchemish, Aleppo, Alalakh, Hama, Qatna, Kadesh, Tell Tweini, Byblos, Tyre, Sidon, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Beth-Shean, Tell Dier Alla, and many more.[9]

Ann Killebrew has shown that cities such as Jerusalem were large and important walled settlements in the pre-Israelite Middle Bronze IIB and the Israelite Iron Age IIC period (c. 1800–1550 and c. 720–586 BC), but that during the intervening Late Bronze (LB) and Iron Age I and IIA/B Ages sites like Jerusalem were small, relatively insignificant, and unfortified.[10]

Some recent writing argues that although some collapses may have happened in this period, these may not have been widespread.[1][2][3]

Background

editAdvanced civilizations with extensive trade networks and complex sociopolitical institutions characterized the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1200 BC).[11] Prominent societies (Egyptians, Hittites, Mesopotamians, and Mycenaeans) exhibited monumental architecture, advanced metallurgy, and literacy.[12] Flourishing trade in copper, timber, pottery, and agricultural goods,[11] as well as diplomatic ties progressively deepened their interdependence.[12] Geopolitical powers of the time relied on variations of the palace economy system, in which wealth is first concentrated in a centralized bureaucracy before being redistributed according to the sovereign's agenda,[13] a system which primarily benefits the society's elite.[11] This intricate web of dependencies, coupled with the inflexibility of the palace system, exposed these civilizations to the cascading effects of distant disturbances.[14]

Evidence

editAnatolia

editMany Anatolian sites were destroyed at the Late Bronze Age, and the area appears to have undergone extreme political decentralization. For much of the Late Bronze Age, Anatolia had been dominated by the Hittite Empire, but by 1200 BC, the state was already fragmenting under the strain of famine, plague, and civil war.[citation needed] The Hittite capital of Hattusa was burned at an unknown date in this general period, though it may in fact have been abandoned at that point.[15][16] Karaoğlan,[a] near present-day Ankara, was burned and the corpses left unburied.[18] Many Anatolian sites have destruction layers dating to this general period. Some of them such as Troy were immediately rebuilt, while others such as Kaymakçı were abandoned.[citation needed]

This period appears to have also been a time of migration. For instance, some evidence that the Phrygians arrived in Anatolia during this period, possibly through the Bosporus or over the Caucasus Mountains.[19]

Initially, the Assyrian Empire maintained a presence in the area. However, it gradually withdrew from much of the region for a time in the second half of the 11th century.[citation needed]

Cyprus

editDuring the reign of the Hittite king Tudḫaliya IV (reigned c. 1237–1209 BC), the island was briefly invaded by the Hittites, either to secure the copper resource or as a way of preventing piracy. Shortly afterwards, the island was reconquered by his son Suppiluliuma II around 1200 BC.[20]

There is little evidence of destruction on the island of Cyprus in the years surrounding 1200 BC which marks the separation between the Late Cypriot II (LCII) from the LCIII period.[21] The city of Kition is commonly cited as destroyed at the end of the LC IIC, but the excavator, Vassos Karageorghis, made it expressly clear that it was not destroyed stating, "At Kition, major rebuilding was carried out in both excavated Areas I and II, but there is no evidence of violent destruction; on the contrary, we observe a cultural continuity."[22] Jesse Millek has demonstrated that while it is possible that the city of Enkomi was destroyed, the archaeological evidence is not clear. Of the two buildings dating to the end of the LC IIC excavated at Enkomi, both had limited evidence of burning and most rooms were without any kind of damage.[23] The same can be said for the site of Sinda as it is not clear if it was destroyed since only some ash was found but no other evidence that the city was destroyed like fallen walls or burnt rubble.[24] The only settlement on Cyprus that has clear evidence it was destroyed around 1200 BC was Maa Palaeokastro, which was likely destroyed by some sort of attack,[25] though the excavators were not sure who attacked it, saying, "We might suggest that [the attackers] were 'pirates', 'adventurers' or remnants of the 'Sea Peoples', but this is simply another way of saying that we do not know."[26]

Several settlements on Cyprus were abandoned at the end of the LC IIC or during the first half of the 12th century BC without destruction such as Pyla Kokkinokremmos, Toumba tou Skourou, Alassa, and Maroni-Vournes.[21] In a trend which appears to go against much of the Eastern Mediterranean at this time, several areas of Cyprus, Kition and Paphos, appear to have flourished after 1200 BC during the LC IIIA rather than experiencing any sort of downturn.[21][27]

Greece

editDestruction was heaviest at palaces and fortified sites, and none of the Mycenaean palaces of the Late Bronze Age survived (with the possible exception of the Cyclopean fortifications on the Acropolis of Athens). Thebes was one of the earliest examples of this, having its palace sacked repeatedly between 1300 and 1200 BC and eventually completely destroyed by fire. The extent of this destruction is highlighted by Robert Drews, who reasons that the destruction was such that Thebes did not resume a significant position in Greece until at least the late 12th century BC.[28] Many other sites offer less conclusive causes; for example it is unclear what happened at Athens, although it is clear that the settlement saw a significant decline during the Bronze Age Collapse. While there is no evidence of remnants of a destroyed palace or central structure, a change in location of living quarters and burial sites demonstrates a significant recession.[29] Furthermore, the increase in fortification at this site suggests much fear of the decline in Athens. Vincent Desborough asserts that this is evidence of later migrations away from the city in reaction to its initial decline, although a significant population did remain.[30] It remains possible that this emigration from Athens was not flight from violence. Nancy Demand posits that environmental changes could have played an important role in the collapse of Athens. In particular Demand notes the presence of "enclosed and protected means of access to water sources at Athens" as evidence of persistent droughts in the region that could have resulted in a fragile reliance on imports.[31]

Up to 90% of small sites in the Peloponnese were abandoned, suggesting a major depopulation. Again, as with many of the sites of destruction in Greece, it is unclear how a lot of this destruction came about. The city of Mycenae for example was initially destroyed in an earthquake in 1250 BC as evidenced by the presence of crushed bodies buried in collapsed buildings.[31] However, the site was rebuilt only to face destruction in 1190 BC as the result of a series of major fires. There is a suggestion by Robert Drews that the fires could have been the result of an attack on the site and its palace; however, Eric Cline points out the lack of archaeological evidence for an attack.[32][33] Thus, while fire was definitely the cause of the destruction, it is unclear what or who caused it. A similar situation occurred Tiryns in 1200 BC, when an earthquake destroyed much of the city including its palace. It is likely however that the city continued to be inhabited for some time following the earthquake. As a result, there is a general agreement that earthquakes did not permanently destroy Mycenae or Tiryns because, as is highlighted by Guy Middleton, "Physical destruction then cannot fully explain the collapse".[34] Drews points out that there was continued occupation at these sites, accompanied by attempts to rebuild, demonstrating the continuation of Tiryns as a settlement.[29] Demand suggests instead that the cause could again be environmental, particularly the lack of homegrown food and the important role of palaces in managing and storing food imports, implying that their destruction only stood to exacerbate the more crucial factor of food shortage.[31] The importance of trade as a factor is supported by Spyros Iakovidis, who points out the lack of evidence for violent or sudden decline in Mycenae.[35]

Pylos offers some more clues to its destruction, as the intensive and extensive destruction by fire around 1180 BC reflects the violent destruction of the city.[36] There is some evidence of Pylos expecting a seaborne attack, with tablets at Pylos discussing "Watchers guarding the coast".[37] Eric Cline rebuts the idea that this is evidence of an attack by Sea People, pointing out that the tablet does not say what is being watched for or why. Cline does not see naval attacks as playing a role in Pylos's decline.[36] Demand, however, argues that, regardless of what the threat from the sea was, it likely played a role in the decline, at least in hindering trade and perhaps vital food imports.[38]

The Bronze Age collapse marked the start of what has been called the Greek Dark Ages, which lasted roughly 400 years and ended with the establishment of Archaic Greece. Other cities, such as Athens, continued to be occupied, but with a more local sphere of influence, limited evidence of trade and an impoverished culture, from which it took centuries to recover.

These sites in Greece show evidence of the collapse:

Iolkos[39] – Knossos – Kydonia – Lefkandi – Menelaion – Mycenae – Nichoria – Pylos – Teichos Dymaion – Tiryns – Thebes, Greece[attribution needed]

Egypt

editWhile it survived the Bronze Age collapse, the Egyptian Empire of the New Kingdom era receded considerably in territorial and economic strength during the mid-twelfth century (during the reign of Ramesses VI, 1145 to 1137). Previously, the Merneptah Stele (c. 1200) spoke of attacks (Libyan War) from Putrians (from modern Libya), with associated people of Ekwesh, Shekelesh, Lukka, Shardana and Teresh (possibly an Egyptian name for the Tyrrhenians or Troas), and a Canaanite revolt, in the cities of Ashkelon, Yenoam and among the people of Israel. A second attack (Battle of the Delta and Battle of Djahy) during the reign of Ramesses III (1186–1155) involved Peleset, Tjeker, Shardana and Denyen.

The Nubian War, the First Libyan War, the Northern War and the Second Libyan War were all victories for Ramesses. Due to this, however, the economy of Egypt fell into decline and state treasuries were nearly bankrupt. By defeating the Sea People, Libyans, and Nubians, the territory around Egypt was safe during the collapse of the Bronze Age, but military campaigns in Asia depleted the economy. With his victory over the Sea People, Ramesses III stated, "My sword is great and mighty like that of Montu. No land can stand fast before my arms. I am a king rejoicing in slaughter. My reign is calmed in peace." With this claim, Ramesses implied that his reign was safe in the wake of the Bronze Age collapse.[40]

Egypt's withdrawal from the southern Levant was a protracted process lasting some one hundred years and was most likely a product of the political turmoil in Egypt proper. Many Egyptian garrisons or sites with an "Egyptian governor's residence" in the southern Levant were abandoned without destruction including Dier el-Balah, Ashkelon, Tel Mor, Tell el-Far'ah (South), Tel Gerisa, Tell Jemmeh, Tel Masos, and Qubur el-Walaydah.[41] Not all Egyptian sites in the southern Levant were abandoned without destruction. The Egyptian garrison at Aphek was destroyed, likely in an act of warfare at the end of the 13th century.[42] The Egyptian gate complex uncovered at Jaffa was destroyed at the end of the 12th century between 1134 and 1115 based on C14 dates,[43] while Beth-Shean was partially though not completely destroyed, possibly by an earthquake, in the mid-12th century.[41]

The Levant

editEgyptian evidence shows that from the reign of Horemheb (ruled either 1319 or 1306 to 1292 BC), wandering Shasu were more problematic than the earlier Apiru. Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC) campaigned against them, pursuing them as far as Moab, where he established a fortress, after a near defeat at the Battle of Kadesh. During the reign of Merneptah, the Shasu threatened the "Way of Horus" north from Gaza. Evidence shows that Deir Alla (Succoth) was destroyed, likely by an earthquake, after the reign of Queen Twosret (r. 1191–1189 BC) though the date of this destruction appears to be much later dating to roughly 1150 BC.[44]

There is little evidence that any major city or settlement in the southern Levant was destroyed around 1200 BC.[45] At Lachish, the Fosse Temple III was ritually terminated while a house in Area S appears to have burned in a house fire as the most severe evidence of burning was next to two ovens while no other part of the city had evidence of burning. After this though the city was rebuilt in a grander fashion than before.[46] For Megiddo, most parts of the city did not have any signs of damage and it is only possible that the palace in Area AA might have been destroyed though this is not certain.[45] While the monumental structures at Hazor were indeed destroyed, this destruction was in the mid-13th century long before the end of the Late Bronze Age began.[47] However, many sites were not burned to the ground around 1200 BC including: Ashkelon, Ashdod, Tell es-Safi, Tel Batash, Tel Burna, Tel Dor, Tel Gerisa, Tell Jemmeh, Khirbet Rabud, Tel Zeror, and Tell Abu Hawam among others.[48][45][44][41]

During the reign of Ramesses III, Philistines were allowed to resettle the coastal strip from Gaza to Joppa, Denyen (possibly the tribe of Dan in the Bible, or more likely the people of Adana, also known as Danuna, part of the Hittite Empire) settled from Joppa to Acre, and Tjekker in Acre. The sites quickly achieved independence, as the Tale of Wenamun shows.

Despite many theories which claim that trade relations broke down after 1200 in the southern Levant, there is ample evidence that trade with other regions continued after the end of the Late Bronze Age in the Southern Levant. Archaeologist Jesse Millek has shown that while the common assumption is that trade in Cypriot and Mycenaean pottery ended around 1200 BC, trade in Cypriot pottery actually largely came to an end at 1300 BC, while for Mycenaean pottery, this trade ended at 1250 BC, and destruction around 1200 BC could not have affected either pattern of international trade since it ended before the end of the Late Bronze Age.[49][50] He has also demonstrated that trade with Egypt continued after 1200 BC.[51] Archaeometallurgical studies performed by various teams have also shown that trade in tin, a non-local metal necessary to make bronze, did not stop or decrease after 1200 BC,[52][53] even though the closest sources of the metal were modern Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, or perhaps even Cornwall, England. Lead from Sardinia was still being imported to the southern Levant after 1200 BC during the early Iron Age.[54]

These sites in the Southern Levant show evidence of the collapse:

Akko – Ashdod – Ashkelon – Beth Shemesh – Bethel – Deir 'Alla (Sukkot) – Tel Lachish – Tel Hazor – Tel Megiddo[attribution needed]

Mesopotamia

editThe Middle Assyrian Empire (1392–1056 BC) had destroyed the Hurrian-Mitanni Empire, annexed much of the Hittite Empire and eclipsed the Egyptian Empire. At the beginning of the Late Bronze Age collapse, it controlled an empire stretching from the Caucasus Mountains in the north to the Arabian Peninsula in the south, and from Ancient Iran in the east to Cyprus in the west. However, in the 12th century BC, Assyrian satrapies in Anatolia came under attack from the Mushki (who may have been Phrygians) and those in the Levant from Arameans, but Tiglath-Pileser I (reigned 1114–1076 BC) was able to defeat and repel these attacks, conquering the attackers. The Middle Assyrian Empire survived intact throughout much of this period, with Assyria dominating and often ruling Babylonia directly, and controlling southeastern and southwestern Anatolia, northwestern Iran and much of northern and central Syria and Canaan, as far as the Mediterranean and Cyprus.[55]

The Arameans and Phrygians were subjugated, and Assyria and its colonies were not threatened by the Sea Peoples who had ravaged Egypt and much of the East Mediterranean, and the Assyrians often conquered as far as Phoenicia and the East Mediterranean. However, after the death of Ashur-bel-kala in 1056, Assyria withdrew to areas close to its natural borders, encompassing what is today northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, the fringes of northwestern Iran, and southeastern Turkey. It still retained a stable monarchy, the best army in the world, and an efficient civil administration, enabling it to survive the Bronze Age Collapse intact. Assyrian written records remained numerous and the most consistent in the world during the period, and the Assyrians were still able to mount long range military campaigns in all directions when necessary. From the late 10th century BC, Assyria once more asserted itself internationally, and the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to be the largest the world had yet seen.[55]

The situation in Babylonia was very different. After the Assyrian withdrawal, it was still subject to periodic Assyrian (and Elamite) subjugation, and new groups of Semitic speakers such as the Arameans and Suteans (and in the period after the Bronze Age Collapse, Chaldeans also) spread unchecked into Babylonia from the Levant, and the power of its weak kings barely extended beyond the city limits of Babylon. Babylon was sacked by the Elamites under Shutruk-Nahhunte (c. 1185–1155 BC), and lost control of the Diyala River valley to Assyria.

Syria

editAncient Syria had been initially dominated by a number of indigenous Semitic-speaking peoples. The East Semitic-speaking polities of Ebla and the Akkadian Empire and the Northwest Semitic-speaking Amorites ("Amurru") and the people of Ugarit were prominent among them.[56] Syria during this time was known as "The land of the Amurru".

Before and during the Bronze Age Collapse, Syria became a battleground between the Hittites, the Middle Assyrian Empire, the Mitanni and the New Kingdom of Egypt between the 15th and late 13th centuries BC, with the Assyrians destroying the Hurri-Mitanni empire and annexing much of the Hittite empire. The Egyptian empire had withdrawn from the region after failing to overcome the Hittites and being fearful of the ever-growing Assyrian might, leaving much of the region under Assyrian control until the late 11th century BC. Later the coastal regions came under attack from the Sea Peoples. During this period, from the 12th century BC, the incoming Northwest Semitic-speaking Arameans came to demographic prominence in Syria, the region outside of the Canaanite-speaking Phoenician coastal areas eventually came to speak Aramaic and the region came to be known as Aramea and Eber Nari.

The Babylonians belatedly attempted to gain a foothold in the region during their brief revival under Nebuchadnezzar I in the 12th century BC, but they too were overcome by their Assyrian neighbors. The modern term "Syria" is a later Indo-European corruption of "Assyria", which only became formally applied to the Levant during the Seleucid Empire (323–150 BC) (see Etymology of Syria).

Levantine sites previously showed evidence of trade links with Mesopotamia (Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia), Anatolia (Hattia, Hurria, Luwia and later the Hittites), Egypt and the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age. Evidence at Ugarit shows that the destruction there occurred after the reign of Merneptah (r. 1213–1203 BC) and even the fall of Chancellor Bay (d. 1192 BC). The last Bronze Age king of Ugarit, Ammurapi, was a contemporary of the last-known Hittite king, Suppiluliuma II. The exact dates of his reign are unknown.

A letter by the king is preserved on one of the clay tablets found baked in the conflagration of the destruction of the city. Ammurapi stresses the seriousness of the crisis faced by many Levantine states due to attacks. In response to a plea for assistance from the king of Alasiya, Ammurapi highlights the desperate situation Ugarit faced in letter RS 18.147:

My father, behold, the enemy's ships came (here); my cities(?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots(?) are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka? ... Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.[57]

Eshuwara, the senior governor of Cyprus, responded in letter RS 20.18:

As for the matter concerning those enemies: (it was) the people from your country (and) your own ships (who) did this! And (it was) the people from your country (who) committed these transgression(s) ... I am writing to inform you and protect you. Be aware![58]

The ruler of Carchemish sent troops to assist Ugarit, but Ugarit was sacked. Letter RS 19.011 (KTU 2.61)[59] sent from Ugarit following the destruction said:

To Ž(?)rdn, my lord, say: thy messenger arrived. The degraded one trembles, and the low one is torn to pieces. Our food in the threshing floors is sacked and the vineyards are also destroyed. Our city is sacked, and may you know it![60]

This quote is frequently interpreted as "the degraded one", referring to the army being humiliated, destroyed, or both.[58] The letter is also quoted with the final statement "Mayst thou know it"/"May you know it" repeated twice for effect in several later sources, while no such repetition appears to occur in the original.

The destruction levels of Ugarit contained Late Helladic IIIB ware, but no LH IIIC (see Mycenaean Greece). Therefore, the date of the destruction is important for the dating of the LH IIIC phase. Since an Egyptian sword bearing the name of Pharaoh Merneptah was found in the destruction levels, 1190 BC was taken as the date for the beginning of the LH IIIC. A cuneiform tablet found in 1986 shows that Ugarit was destroyed after the death of Merneptah. It is generally agreed that Ugarit had already been destroyed by the eighth year of Ramesses III, 1178 BC. Letters on clay tablets that were baked in the conflagration caused by the destruction of the city speak of attack from the sea, and a letter from Alashiya (Cyprus) speaks of cities already being destroyed by attackers who came by sea.

There is clear evidence that Ugarit was destroyed in some kind of assault, though the exact assailant is not known. In one residential area called the Ville sud, thirty two arrowheads were found scattered throughout the area while twelve of the arrowheads were found on the streets and in the open spaces. Along with the arrowheads, two lance heads, four javelin heads, five bronze daggers, one bronze sword, and three bronze pieces of armor were scattered throughout the houses and streets suggesting a fight took place in this residential neighborhood. An additional twenty-five arrowheads were also recovered scattered around the city centre, all of which suggests the city was burnt by an assault not by an earthquake.[61] At the city of Emar, on the Euphrates, at some time between 1187 and 1175 only the monumental and religious structures were targeted for destruction while the houses appear to have been emptied, abandoned and were not destroyed with the monumental structures which suggests that the city was burned by attackers even though no weapons were recovered.[62]

While certain cities such as Ugarit and Emar were destroyed at the end of the Late Bronze Age, there are several others which were not destroyed even though they erroneously appear on most maps of destruction from the end of the Late Bronze Age. No evidence of destruction has been found at Hama, Qatna, Kadesh, Alalakh, and Aleppo, while for Tell Sukas, archaeologists only found some minor burning on some floors likely indicating that the town was not burned to the ground around 1200 BC.[63]

The West Semitic Arameans eventually superseded the earlier Amorites and people of Ugarit. The Arameans, together with the Phoenicians and the Syro-Hittite states came to dominate most of the region demographically; however, these people, and the Levant in general, were also conquered and dominated politically and militarily by the Middle Assyrian Empire until Assyria's withdrawal in the late 11th century BC, although the Assyrians continued to conduct military campaigns in the region. However, with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the late 10th century BC, the entire region once again fell to Assyria.

These sites in Syria show evidence of the collapse:

Alalakh – Aleppo – Emar – Hama – Kadesh (Syria) – Qatna – Tell Sukas - Ugarit[attribution needed]

Possible causes

editVarious mutually compatible explanations for the collapse have been proposed, including climatic changes, migratory invasions by groups such as the Sea Peoples, the spread of iron metallurgy, military developments, and a range of political, social and economic systems failures, but none have achieved consensus. Earthquakes have also been proposed as causal, but recent research suggests that earthquakes were not as influential as previously believed.[64] It is likely that a combination of several factors is responsible.

General systems collapse theory, pioneered by Joseph Tainter, proposes that societal collapse results from an increase in social complexity beyond a sustainable level, leading people to revert to simpler ways of life.[65] The growing complexity and specialization of the Late Bronze Age political, economic, and social organization made the organization of civilization too intricate to reestablish once seriously disrupted.[66] The critical flaws of the Late Bronze Age (its centralization, specialization, complexity, and top-heavy political structure) were exposed by sociopolitical events (revolt of peasantry and defection of mercenaries), fragility of all kingdoms (Mycenaean, Hittite, Ugaritic, and Egyptian), demographic crises (overpopulation), and wars between states. Other factors that could have placed increasing pressure on the fragile kingdoms include piracy by the Sea Peoples interrupting maritime trade, as well as drought, crop failure, famine, or the Dorian migration or invasion.[67]

Drought

editA diversion of midwinter storms from the Atlantic to north of the Pyrenees and the Alps brought wetter conditions to Central Europe and drought to the Eastern Mediterranean near the time of the Late Bronze Age collapse.[34] During what may have been the driest era of the Late Bronze Age, tree cover of the Mediterranean forest dwindled. Juniper tree ring measurements in the Anatolia region demonstrate a severe dry period from c.1198 to c.1196 BC.[68] In the Dead Sea region (The Southern Levant), the subsurface water level dropped by more than 50 meters during the end of the second millennium BC. According to the geography of that region, for water levels to drop so drastically the amount of rain the surrounding mountains received would have been dismal.[69] Using the Palmer Drought Index for 35 Greek, Turkish and Middle Eastern weather stations, it was shown that a persistent drought like the one that began in January 1972 AD would have affected all of the sites associated with the Late Bronze Age collapse.[70]

Alternatively, changes at the end of the Bronze Age could be better characterized as a 'gear shift' in Mediterranean climate rather than an event of three years. The long-range shift in precipitation would not have been a crisis event, but rather a continual stress put on societies in the region over several generations. There was no one year where conditions became untenable, "nor one straw that broke the back of the camel."[71]

Analysis of multiple lines of paleoenvironmental evidence suggests climate change was one aspect associated with this period, but not the sole cause.[72] This was also the conclusion reached by Knapp and Manning in 2016 who concluded that, "Based on a series of proxy indicators, there is clearly some sort of shift to cooler and more arid and unstable conditions generally between the 13th and 10th centuries BC, but not necessarily any one key "episode"; thus, there is a context for change but not necessarily its only or specific cause."[69] Moreover, Karakaya and Riehl's recent study of ancient plant remains from Syria showed little evidence that plants underwent water stress during the Late Bronze Age to Iron Age transition. As they summarize their research, "The emerging picture as concerns plant subsistence is that there is no clear evidence that the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age were periods of dearth and widespread famine, as some climate models have presupposed."[73]

Ironworking

editThe Bronze Age collapse may be seen in the context of a technological history that saw the slow spread of ironworking technology from present-day Bulgaria and Romania in the 13th and the 12th centuries BC.[74] Leonard R. Palmer suggested that iron, which is superior to bronze for weapons manufacturing, was in more plentiful supply and so allowed larger armies of iron users to overwhelm the smaller bronze-equipped armies that consisted largely of Maryannu chariotry.[75]

Migratory invasions

editPrimary sources report that the era was marked by large-scale migration of people at the end of the Late Bronze Age. Drought in the Nile Valley also may have contributed to the rise of the Sea Peoples and their sudden migration across the eastern Mediterranean. It was suspected that crop failures, famine and the population reduction that resulted from the lackluster flow of the Nile and the migration of the Sea Peoples led to New Kingdom Egypt falling into political instability at the end of the Late Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age. A general systems collapse has been put forward as an explanation for the reversals in culture that occurred between the Urnfield culture of the 13th and 12th centuries BC and the rise of the Celtic Hallstatt culture in the 9th and 10th centuries BC.[76]

Pandemic

editRecent evidence suggests the collapse of the cultures in Mycenaean Greece, Hittite Anatolia, and the Levant may have been precipitated or worsened by the arrival of an early and now-extinct strain of the bubonic plague brought from central Asia by the Sea Peoples or other migrating groups.[77]

Volcanoes

editSome Egyptologists have dated the Hekla 3 volcanic eruption in Iceland to 1159 BC and blamed it for famines under Ramesses III during the wider Bronze Age collapse.[78] The event is thought to have caused a volcanic winter. Other estimated dates for the Hekla 3 eruption range from 1021 (±130)[79] to 1135 BC (±130)[79] and 929 (±34).[80][81] Other scholars prefer the neutral and vague "3000 BP".[82]

Warfare

editRobert Drews argues[83] for the appearance of massed infantry, using newly developed weapons and armour, such as cast rather than forged spearheads and long swords, a revolutionizing cut-and-thrust weapon,[84] and javelins. The appearance of bronze foundries suggests "that mass production of bronze artefacts was suddenly important in the Aegean". For example, Homer uses "spears" as a metonym for "warriors".

Such new weaponry, in the hands of large numbers of "running skirmishers", who could swarm and cut down a chariot army, would destabilize states that were based upon the use of chariots by the ruling class. That would precipitate an abrupt social collapse as raiders began to conquer, loot and burn cities.[39][85]

Aftermath

editRobert Drews described the collapse as "arguably the worst disaster in ancient history, even more calamitous than the collapse of the Western Roman Empire".[86] Cultural memories of the disaster told of a "lost golden age". For example, Hesiod spoke of Ages of Gold, Silver, and Bronze, separated from the cruel modern Age of Iron by the Age of Heroes. Rodney Castleden suggests that memories of the Bronze Age collapse influenced Plato's story of Atlantis in Timaeus and the Critias.

Only a few powerful states survived the Bronze Age collapse, particularly Assyria (albeit temporarily weakened), the New Kingdom of Egypt (also weakened), the Phoenician city-states and Elam. Even among these comparative survivors, success was mixed. By the end of the 12th century BC, Elam waned after its defeat by Nebuchadnezzar I, who briefly revived Babylonian fortunes before suffering a series of defeats by the Assyrians. After the death of Ashur-bel-kala in 1056 BC, Assyria declined for a century. Its empire shrank significantly by 1020 BC, apparently leaving it in control only of the areas in its immediate vicinity, although its heartland remained well-defended. By the time of Wenamun, Phoenicia had regained independence from Egypt.

Gradually, by the end of the ensuing Dark Age, remnants of the Hittites coalesced into small Syro-Hittite states in Cilicia and in the Levant, where the new states were composed of mixed Hittite and Aramean polities. Beginning in the mid-10th century BC, a series of small Aramean kingdoms formed in the Levant, and the Philistines settled in southern Canaan, where Canaanite speakers had coalesced into a number of polities such as Israel, Moab, Edom and Ammon.

See also

edit- Greek Dark Ages – period following the Late Bronze Age collapse

- Iron Age Cold Epoch

- Middle Bronze Age migrations (ancient Near East)

- Migration Period – similar period preceding the Early Middle Ages

- Mycenology

- Third Intermediate Period of Egypt – a similar period in Egypt

- Late Harappan period, Indo-Aryan migrations – events and periods connected to the end of the Bronze Age India

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Middleton, Guy D. (25 February 2024). "Getting closer to the Late Bronze Age collapse in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean, c. 1200 BC". Antiquity. 98 (397): 260–263. doi:10.15184/aqy.2023.187 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Millek, Jesse (2023). Destruction and Its Impact on Ancient Societies at the End of the Bronze Age. Columbus, GA: Lockwood. ISBN 978-1-948488-83-9.

- ^ a b Jung, Reinhard; Kardamaki, Eleftheria (2022). Synchronizing the Destructions of the Mycenaean Palaces. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-3-7001-8877-3.

- ^ Millek, Jesse (2021). "Why Did the World End in 1200 BCE". Ancient Near East Today. 9 (8). Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ For Syria, see M. Liverani, "The collapse of the Near Eastern regional system at the end of the Bronze Age: the case of Syria" in Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World, M. Rowlands, M. T. Larsen, K. Kristiansen, eds. (Cambridge University Press) 1987.

- ^ S. Richard, "Archaeological sources for the history of Palestine: The Early Bronze Age: The rise and collapse of urbanism", The Biblical Archaeologist (1987)

- ^ Crawford, Russ (2006). "Chronology". In Stanton, Andrea; Ramsay, Edward; Seybolt, Peter J; Elliott, Carolyn (eds.). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. Sage. p. xxix. ISBN 978-1412981767. Archived from the original on 2 June 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ The physical destruction of palaces and cities is the subject of Robert Drews's The End of the Bronze Age: changes in warfare and the catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C., 1993.

- ^ Millek, Jesse (2022). "The Fall of the Bronze Age and the Destruction that Wasn't". Ancient Near East Today. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Killebrew, Ann E. (2003). "Biblical Jerusalem: An Archaeological Assessment". In Killebrew, Ann E.; Vaughn, Andrew G. (eds.). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830660. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Orphanides, Andreas G. (January 2017). "Late Bronze Age Socio-Economic and Political Organization, and the Hellenization of Cyprus". Athens Journal of History. 3 (1): 7–20. doi:10.30958/ajhis.3-1-1.

- ^ a b Mark, Joshua J. (20 September 2019). "Bronze Age Collapse". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ de Blois, Lukas; van der Spek, R. J. (1997). An Introduction to the Ancient World. Translated by Mellor, Susan. Routledge. pp. 56–60. ISBN 0415127734.

- ^ Cline 2014, p. 165.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2001). "Die Zerstörung der Stadt Hattusa, in: G. Wilhelm (Hrsg.), Akten des IV. Internationalen Kongresses für Hethitologie. Studien zu den Boğazköy-Texten 45 (Wiesbaden 2001) 623–634". Akten des IV. Internationalen Kongresses für Hethitologie. Studien zu den Boğazköy-Texten 45. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2010). "After the Empire: Observations on the Early Iron Age in Central Anatolia, in: I. Singer (ed.), ipamati kistamati pari tumatimis. Luwian and Hittite Studies presented to J. David Hawkins on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday (Tel Aviv 2010) 220–229". Ipamati Kistamati Pari Tumatimis. Luwian and Hittite Studies Presented to J. David Hawkins on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday: 221. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Robbins, p. 170

- ^ Drews, Robert (1995). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0691025919. Archived from the original on 2 June 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Bryce, Trevor. The Kingdom of the Hittites. (Clarendon), p. 379

- ^ Bryce, Trevor. The Kingdom of the Hittites (Clarendon), p. 366.

- ^ a b c Georgiou, Artemis (3–4 November 2014). "Flourishing amidst a 'Crisis': the regional history of the Paphos polity during the transition from the 13th to the 12th centuries BCE". In Fischer, P. and Burge, T. (eds.). 'Sea Peoples' Up-to-Date: New Research on Transformations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 13th−11th Centuries BCE. Proceedings of the ESF-Workshop. Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Karageorghis, Vassos (1992). "The Crisis Years: Cyprus". In Ward, W. A. and Joukowsky, M. S. (eds.). The Crisis Years: The 12th Century B.C. From Beyond the Danube to the Tigris. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt. pp. 79–86. ISBN 9780840371485.

- ^ Millek 2021a, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Millek 2021a, p. 76.

- ^ Millek 2021a, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Karageorghis, Vassos (1988). Excavations at Maa-Palaeokastro 1979–1986. Cyprus Department of Antiquities. p. 266. ISBN 9963-36-409-8. OCLC 19842786. Archived from the original on 2 June 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Iacovou, Maria (2008). "Cultural and Political Configurations in Iron Age Cyprus: The Sequel to a Protohistoric Episode". American Journal of Archaeology. 112 (4): 625–657. doi:10.3764/aja.112.4.625. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 20627513. S2CID 55793645. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Drews 1993, p. 22.

- ^ a b Drews 1993, p. 25.

- ^ Desborough, Vincent R. d'A. (1964). The last Mycenaeans and their successors; an archaeological survey, c. 1200 – c. 1000 B.C. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 113.

- ^ a b c Demand, Nancy H. (2011). The Mediterranean context of early Greek history. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 198. ISBN 9781444342338. OCLC 823737347.

- ^ Drews 1993, p. 23.

- ^ Cline 2014, p. 130.

- ^ a b Middleton, Guy D. (September 2012). "Nothing Lasts Forever: Environmental Discourses on the Collapse of Past Societies". Journal of Archaeological Research. 20 (3): 257–307. doi:10.1007/s10814-011-9054-1. ISSN 1059-0161. S2CID 144866495.

- ^ Cline 2014, p. 131.

- ^ a b Cline 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Ventris, Michael (1959). Documents in Mycenaean Greek: three hundred selected tablets from Knossos, Plyos, and Mycenae with commentary and vocabulary. Cambridge University Press. p. 189. OCLC 70408199.

- ^ Demand, Nancy H. (2011). The Mediterranean context of early Greek history. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 199. ISBN 9781444342338. OCLC 823737347.

- ^ a b Drews 1993.

- ^ "SAOC 12. Historical Records of Ramses III: The Texts in Medinet Habu Volumes 1 and 2 | The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago". oi.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Millek, Jesse Michael (2018). "Destruction and the Fall of Egyptian Hegemony Over the Southern Levant". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 19: 11–15. ISSN 1944-2815. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Millek, Jesse (2017). Sea Peoples, Philistines, and the Destruction of Cities: A Critical Examination of Destruction Layers 'Caused' by the 'Sea Peoples'. In Fischer, P. And T.Burge (eds.), "Sea Peoples" Up-to-Date: New Research on Transformation in the Eastern Mediterranean in 13th–11th Centuries BCE. 113–140 (1 ed.). Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 120–122. ISBN 978-3-7001-7963-4. JSTOR j.ctt1v2xvsn. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Burke et al. 2017 Excavations of the New Kingdom Fortress in Jaffa, 2011–2014: Traces of Resistance to Egyptian Rule in Canaan | American Journal of Archaeology: 85–133". www.ajaonline.org. January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b Millek, Jesse (2019). "Crisis, Destruction, and the End of the Late Bronze Age in Jordan: A Preliminary Survey". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 135 (2): 127–129. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Millek, Jesse (2018). "Just how much was destroyed? The end of the Late Bronze Age in the Southern Levant". Ugarit-Forschungen (49): 239–274. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Millek, Jesse (2017). "Sea Peoples, Philistines, and the Destruction of Cities: A Critical Examination of Destruction Layers 'Caused' by the 'Sea Peoples'". In Fischer, P.; Burge, T. (eds.). Sea Peoples' Up-to-Date: New Research on Transformation in the Eastern Mediterranean in 13th–11th Centuries BCE (1 ed.). Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-3-7001-7963-4. JSTOR j.ctt1v2xvsn. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Amnon; Zuckerman, Sharon (2008). "Hazor at the End of the Late Bronze Age: Back to Basics". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 350 (350): 1–6. doi:10.1086/BASOR25609263. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 25609263. S2CID 163208536. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Millek 2019a, pp. 147–188.

- ^ Millek 2019a, pp. 180–212.

- ^ Millek, Jesse Michael (2022). "The impact of destruction on trade at the end of the Late Bronze Age in the Southern Levant". In Hagemeyer, Felix (ed.). Jerusalem and the Coastal Plain in the Iron Age and Persian Periods New Studies on Jerusalem's Relations with the Southern Coastal Plain of Israel/Palestine (C. 1200–300 BCE) Research on Israel and Aram in Biblical Times IV. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 39–60. ISBN 978-3-16-160692-2. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Millek 2019a, pp. 217–238.

- ^ Yahalom-Mack, Naama (2014). "New Insights to Levantine Copper Trade: Analysis of Ingots from the Bronze and Iron Ages in Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 45: 159–177. Bibcode:2014JArSc..45..159Y. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.02.004. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Ashkenazi, D.; Bunimovitz, S.; Stern, A. (2016). "Archaeometallurgical Investigation of Thirteenth-Twelfth Centuries BCE Bronze Objects from Tel Beth-Shemesh, Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 6: 170–181. Bibcode:2016JArSR...6..170A. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.02.006. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Yagel, Omri; Ben-Yosef, Erez (2022). "Lead in the Levant during the Late Bronze and early Iron Ages". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 46: 103649. Bibcode:2022JArSR..46j3649Y. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103649. ISSN 2352-409X. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ a b Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq

- ^ Woodard, Roger D. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1139469340. Archived from the original on 2 June 2024. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Jean Nougaryol et al. (1968) Ugaritica V: 87–90 no. 24

- ^ a b Cline 2014, p. 151.

- ^ Dietrich, M.; Loretz, O.; Sanmartín, J. "Archival view of P521115". Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Astour, Michael C. (1965). "New Evidence on the Last Days of Ugarit". American Journal of Archaeology. 69 (3): 258. doi:10.2307/502290. JSTOR 502290. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Millek, Jesse (2020). "Our city is sacked. May you know it!; The Destruction of Ugarit and its Environs by the Sea Peoples". Archaeology and History of Lebanon. 52–53: 105–108. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Millek 2019b, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Millek 2019b.

- ^ Millek, Jesse (2023). "Destruction and Its Impact on Ancient Societies at the End of the Bronze Age". Lockwood Press.

- ^ Tainter, Joseph (1976). The Collapse of Complex Societies (Cambridge University Press).

- ^ Thomas, Carol G.; Conant, Craig. (1999) Citadel to City-state: The Transformation of Greece, 1200–700 B.C.E.,

- ^ Cline 2014.

- ^ Sturt W. Manninget al. Severe multi-year drought coincident with Hittite collapse around 1198–1196 BC Archived 17 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 08 February 2023

- ^ a b a. Bernard Knapp; Sturt w. Manning (2016). "Crisis in Context: The End of the Late Bronze Age in the Eastern Mediterranean". American Journal of Archaeology. 120: 99–149. doi:10.3764/aja.120.1.0099. S2CID 191385013.

- ^ Weiss, Harvey (June 1982). "The decline of Late Bronze Age civilization as a possible response to climatic change". Climatic Change. 4 (2): 173–198. doi:10.1007/BF00140587. S2CID 154059624.

- ^ Drake, Brandon L. (2012). "The influence of climatic change on the Late Bronze Age Collapse and the Greek Dark Ages" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (6): 1866. Bibcode:2012JArSc..39.1862D. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.029. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Hazell, Calian J; Pound, Matthew J; Hocking, Emma P (23 April 2022). "High-resolution Bronze Age palaeoenvironmental change in the eastern Mediterranean: exploring the links between climate and societies". Palynology. 46 (4): 2067259. Bibcode:2022Paly...4667259H. doi:10.1080/01916122.2022.2067259. S2CID 252971820.

- ^ Riehl, Simone; Karakaya, Doğa (2019–2020). "Subsistence in Post-Collapse Societies: Patterns of Agroproduction from the Late Bronze Age to Iron Age in the Northern Levant and Beyond". Archaeology & History in the Lebanon: 155. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ See A. Stoia and the other essays in M.L. Stig Sørensen and R. Thomas, eds., The Bronze Age: Iron Age Transition in Europe (Oxford) 1989, and T.A. Wertime and J.D. Muhly, The Coming of the Age of Iron (New Haven) 1980.

- ^ Palmer, Leonard R (1962). Mycenaeans and Minoans: Aegean Prehistory in the Light of the Linear B Tablets. New York, Alfred A. Knopf

- ^ History of Castlemagner, on the web page of the local historical society. Archived 16 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Neumann, Gunnar; Skourtanioti, Eirini; Burri, Marta (25 July 2022). "Ancient Yersinia pestis and Salmonella enterica genomes from Bronze Age Crete". Current Biology. 32 (16): 3641–3649.e8. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E3641N. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.094. PMID 35882233. S2CID 251044525.

- ^ Yurco, Frank J. (1999). "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause". In Teeter, Emily; Larson John (eds.). Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Vol. 58. Chicago, IL: Oriental Institute of the Univ. of Chicago. pp. 456–458. ISBN 1-885923-09-0.

- ^ a b Baker, Andy; et al. (1995). "The Hekla 3 volcanic eruption recorded in a Scottish speleothem?". The Holocene. 5 (3): 336–342. Bibcode:1995Holoc...5..336B. doi:10.1177/095968369500500309. S2CID 130396931.

- ^ Dugmore AJ, Cook GT, Shore JS, Newton AT, Edwards KJ, Larsen G (1995). "Radiocarbon Dating Tephra Layers in Britain and Iceland". Radiocarbon. 37 (2): 379–388. Bibcode:1995Radcb..37..379D. doi:10.1017/S003382220003085X.

- ^ Late Holocene solifluction history reconstructed using tephrochronology Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Martin P. Kirkbride & Andrew J. Dugmore, Geological Society, London, Special Publications; 2005; v. 242; p. 145-155.

- ^ Towards a Holocene Tephrochronology for Sweden Archived 7 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Stefan WastegÅrd, XVI INQUA Congress, Paper No. 41-13, Saturday, July 26, 2003.

- ^ Drews 1993, pp. 192ff.

- ^ Drews 1993, p. 194.

- ^ McGoodwin, Michael. "Drews (Robert) End of Bronze Age Summary". mcgoodwin.net. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ Drews 1993: 3

Sources

edit- Cline, Eric H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14089-6.

- Drews, Robert (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04811-6.

- Millek, Jesse Michael (2019a). Exchange, Destruction, and a Transitioning Society. Interregional Exchange in the Southern Levant from the Late Bronze Age to the Iron I. Tübingen: Tübingen University Press. ISBN 978-3-947251-11-7.

- Millek, Jesse Michael (2019b). "Destruction at the end of the Late Bronze Age in Syria: A reassessment". Studia Eblaitica. 5: 157–190. doi:10.13173/STEBLA/2019/1/157. ISBN 978-3-447-11300-7. S2CID 259490258.

- Millek, Jesse Michael (2021a). "Just what did they destroy? The Sea Peoples and the end of the Late Bronze Age". In Kamlah, J.; Lichtenberger, A. (eds.). The Mediterranean Sea and the Southern Levant: archaeological and historical perspectives from the Bronze Age to Medieval times. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 59–98. ISBN 978-3-447-11742-5.

Further reading

edit- Bachhuber, Christoph R. and Gareth Roberts, 2009. Forces of Transformation : The End of the Bronze Age in the Mediterranean : Proceedings of an International Symposium Held at St. John's College University of Oxford 25–6th March 2006 Paperback ed. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Dickinson, Oliver (2007). The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age: Continuity and Change Between the Twelfth and Eighth Centuries BC. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415135900.

- Fischer, Peter M. and Teresa Bürge, 2017. "Sea Peoples" Up-To-Date : New Research on Transformations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 13th-11th Centuries Bce. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctt1v2xvsn.

- Killebrew Ann E. and Gunnar Lehmann, 2013. The Philistines and Other "Sea Peoples" in Text and Archaeology. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

- Millek, Jesse (2023). Destruction and its impact on ancient societies at the end of the Bronze Age. Columbus (Ga.): Lockwood Press. ISBN 9781948488839.

- Oren, Eliezer D. 2000. The Sea Peoples and Their World : A Reassessment. Philadelphia: University Museum.

- Ward, William A. and Martha Sharp Joukowsky, 1992. The Crisis Years : The 12th Century B.c. : From Beyond the Danube to the Tigris. Dubuque Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Pub.