Inglewood is a city in southwestern Los Angeles County, California, United States, in the Greater Los Angeles metropolitan area. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city had a population of 107,762. It is in the South Bay region of Los Angeles County, near Los Angeles International Airport.[6] The Inglewood area was developed following the opening of the Venice–Inglewood railway in 1887 and incorporated as a city on February 14, 1908.[7]

Inglewood, California | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: "City of Champions" | |

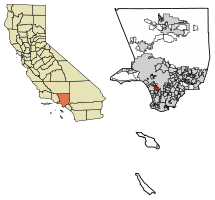

Location of Inglewood in Los Angeles County, California | |

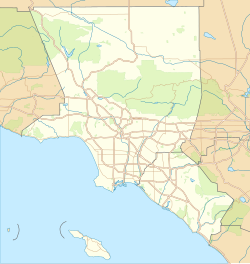

Location within the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area | |

| Coordinates: 33°57′27″N 118°20′46″W / 33.95750°N 118.34611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Established | 1888 |

| Incorporated | February 7, 1908[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager–Commission |

| • Mayor | James T. Butts Jr. |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Eloy Morales Jr. |

| • City Council | George Dotson Alex Padilla Dionne Faulk |

| • City Clerk | Aisha Thompson |

| Area | |

• Total | 9.09 sq mi (23.55 km2) |

| • Land | 9.07 sq mi (23.49 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.06 km2) 0.27% |

| Elevation | 131 ft (40 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 107,762 |

| • Rank | 12th in Los Angeles County 69th in California |

| • Density | 12,000/sq mi (4,600/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes[5] | 90301–90312 |

| Area codes | 310,424, 213/323 |

| FIPS code | 06-36546 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1660799, 2410106 |

| Website | cityofinglewood.org |

The city is a major hub for professional sports with several teams that have played in Inglewood's venues. The Kia Forum, an indoor arena, opened in 1967 and hosted the Los Angeles Lakers of the National Basketball Association, Los Angeles Kings of the National Hockey League, and the Los Angeles Sparks of the Women's National Basketball Association, until the opening of Staples Center in 1999. Two National Football League teams—the Los Angeles Rams and Los Angeles Chargers—have played at SoFi Stadium since it opened in 2020; the stadium will also host the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2028 Summer Olympics. The Los Angeles Clippers of the National Basketball Association began play at Intuit Dome in 2024.

History

editThe earliest residents of what is now Inglewood were Native Americans who used the Aguaje de Centinela natural springs in today's Edward Vincent Sr. Park (known for most of its history as Centinela Park). Local historian Gladys Waddingham wrote that these springs took the name Centinela from the hills that rose gradually around them, and which allowed ranchers to watch over their herds," (thus the name centinelas or sentinels).[8]

Spanish era

editAmong the original settlers of Los Angeles in 1781 was the Spanish soldier Jose Manuel Orchado Machado, "a 23-year-old muleteer from Los Alamos in Sinaloa". These settlers were ordered by the officials of the San Gabriel Mission "to graze their animals on the ocean side of Los Angeles in order not to infringe on mission lands." As a result, the settlers, or pobladores, drove some of their cattle to the "lush pasture lands near Centinela Springs", and the first construction there was done by Bruno Ygnacio Ávila, who received a permit in 1822 to build a "corral and hut for his herders."[8]: unpaged [xiv] The area that is now Inglewood was divided into two rancho grants: Rancho Sausal Redondo and Rancho Aguaje de la Centinela.[9]

Mexican era

editLater, Avila constructed a three-room adobe house on a slight rise overlooking the creek that ran from Centinela Springs all the way to the ocean. According to the LAOkay web site,[10] this adobe was built where the present baseball field is in the park. It no longer exists.

In 1834, Ygnacio Machado, one of the sons of Jose Machado, built the Centinela Adobe,[8]: unpaged [xv] which sits on a rise above the present Interstate 405 (San Diego Freeway) and is used as the headquarters of the Centinela Valley Historical Society.[11] Two years later, Ygnacio[12] was granted the 2,220-acre (9.0 km2) Rancho Aguaje de la Centinela, though this land had already been claimed by Avila.[8]: unpaged [xv]

American era

editDaniel Freeman acquired the rancho and was a founder of the Centinela-Inglewood Land Company in 1887, which developed the city. That year it was reported that:[13]

The Centinela-Inglewood Company has put on a four-horse coach between their office and Inglewood, leaving at 9:30 am and returning at 2 pm to carry passengers desiring to see the property. It is understood that arrangements will soon be completed for frequent fast trains between Los Angeles and Inglewood over the California Southern.

Inglewood Park Cemetery, a widely used cemetery for the entire region, was founded in 1905.[14] The city has been home to the Hollywood Park Racetrack from 1938 to 2013, one of the premier horse racing venues in the United States.[15][16] Fosters Freeze, the first soft serve ice cream chain in California, was founded by George Foster in 1946 in Inglewood.[17] Inglewood was named an All-America City by the National Civic League in 1989 and yet again in 2009 for its visible progress.[18]

The Ku Klux Klan had a presence in Inglewood in the 1920s, with the most notable event being the 1922 raid,[19] the Klan had a chapter in Inglewood as late as October 1931.[20]

Labor unions

editLabor troubles became a serious issue during the early years of World War II as local industries supplied the Allies, against the wishes of Communist local union officials. In 1941, the United Auto Workers (UAW) won the election over the International Association of Machinists and represented all the employees at the North American Aviation factory in Inglewood. UAW negotiators demanded a starting pay of 75 cents an hour, plus a 10-cent raise for the 11,000 current employees. The UAW had made a no-strike pledge, but suddenly a wildcat strike on June 4 closed the plant that produced a fourth of the nation's fighter planes. The UAW was unable to get the workers to return, when Washington intervened. With the approval of national CIO leadership, President Franklin Roosevelt sent in the California national guard to reopen the plant. When Germany suddenly invaded the USSR in late June 1941, though, the Communist activists suddenly became the strongest supporters of war production; they crushed wildcat strikes.[21][22][23]

African-American influence

edit"No blacks had ever lived in Inglewood", Gladys Waddingham wrote,[8]: 59 but by 1960, "they lived in great numbers along its eastern borders. This came to the great displeasure of the predominantly white residents already residing in Inglewood. In 1960, the census counted only 29 "Negroes" among Inglewood's 63,390 residents. Not a single black child attended the city's schools. Real-estate agents refused to show homes to blacks. A rumored curfew kept blacks off the streets at night. Inglewood was a prime target because of its previous history of restrictions." "Fair housing and school busing were the main problems of 1964. The schools were not prepared to handle racial incidents, even though any that occurred were very minor. Adults held many heated community meetings, since the blacks objected to busing as much as did the whites."[8]: 61 In 1969, an organization called "Morningside Neighbors" changed its name to "Inglewood Neighbors" "in the hope of promoting more integration."[8]: 63

On July 22, 1970, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Max F. Deutz ordered Inglewood schools to desegregate in response to a suit filed by 19 parents.[24] At least since 1965, said Deutz, the Inglewood school board had been aware of a growing influx of black families into its eastern areas, but had done nothing about the polarization of its pupils into an eastern black area and a western white one.[25] On August 31, he rejected an appeal by four parents who said the school board was not responsible for the segregation, but that the blacks "selected their places of residence by voluntary choice."[24]

The first black principal among the 18 Inglewood schools was Peter Butler at La Tijera Elementary,[8]: 66 and in 1971, the "Stormy racial meetings in 1971" included a charge by "some real estate men in the overflowing Crozier Auditorium" that the Human Relations Commission was acting like "the Gestapo".[8]: 67 In that year, Loyd Sterling Webb, president of Inglewood Neighbors, became the first black officeholder when voters elected him to the school board.[26]

In 1972, Curtis Tucker Sr., was appointed as the first black city council member.[8]: 69 That year, composer LeRoy Hurte, an African-American, took the baton of the Inglewood Symphony Orchestra and continued to work with it for 20 years.[8]: 75 Edward Vincent Jr. became Inglewood's first black mayor in 1983. In that decade, whites left the city in increasing numbers, and Inglewood became the first city in California to declare the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. a holiday.[8]: 76 Since the term of Edward Vincent Jr. (1983–1997), Inglewood has consecutively elected African-American mayors: Roosevelt F. Dorn (1997–2010), Danny Tabor (2010–2011),[27] and James T. Butts Jr. (2011–present).

Rise of Latino population

editThe 1990 census showed that Latinos in Inglewood had increased by 134% since 1980, the largest jump in the South Bay. Economic factors apparently played a role in where new arrivals settled, said David Heer, a USC professor of sociology and associate director of the university's Population Research Laboratory. "Housing is generally less expensive here than elsewhere . . . and I would say that they receive a warmer welcome here", said Norm Cravens, assistant city manager in Inglewood, where the white population dropped from nearly 21% in 1980 to 8.5% in 1990.[28]

In the 2000 census, blacks made up 47% of the city's residents (53,060 people), and Latinos comprised 46% (51,829), but the Census Bureau estimated that in 2007, the percentage of blacks had declined to 41% (48,252) and that Latinos were at 52.5% (61,847). The white population declined from 19 (21,505) to 17.7% (20,853).[29][30]

That year, though, only one of the city's five city council members was Latino: Jose Fernandez. No Latinos were on the five-member board of education.[31]

Religious history

editIn 2007, the area served by the Inglewood post office (including Lennox) had 98 churches, temples, mosques, chapels and other houses of worship, according to the AreaConnect.com website.[32]

The first church service was held on April 22, 1888, in the Inglewood House hotel on Commercial Street (today's La Brea Avenue), popularly called Mrs. Belden's Boarding House, when Inglewood had only 300 residents and 112 registered voters. Later, services were in Bucephalus Hall, but eventually the congregation moved to Hyde Park, which left Inglewood with no church. On January 19, 1890, Inglewood's first permanent church – Presbyterian – was established on Market Street. A bit later, the [United] Brethren constructed a building on South Market Street.[8]: 6, 10, and 17

In 1907, a group of Episcopalians began services in a private home, and a few years later, the first Catholic services were held in Bank Hall. In 1910, the Presbyterians moved their two buildings, a sanctuary and a manse, to the corner of Grevillea and Nutwood "because the streetcars [on Market Street] were so noisy and threw so much dust and sand fleas in the windows."[8]: 14 and 17

Trash-hauling pact

editIn 2018, an investigation began into a 2012 trash-hauling contract valued at $100 million; it went to a bidder with connections to current mayor James T. Butts. The bidder, Consolidated Disposal Services, secured the contract soon after hiring Michael Butts, brother of Mayor Butts, as an operations manager.[33] Consolidated continues to provide garbage collection services as of 2023.

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.1 square miles (24 km2). Downtown Inglewood is 4.15 miles (6.68 km) from Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). It is part of the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim metropolitan statistical area.[34]

Neighborhoods

editInglewood consists of 10 neighborhoods that are indicated by symbols on street signs. The neighborhoods are: Morningside Park, Downtown Inglewood, Fairview Heights, Arbor Village, Hollypark Knolls, Centinela Heights, Century Heights, Inglewood Knolls, and Lockhaven.[35]

Crenshaw-Imperial

editThe Crenshaw-Imperial district was a later annexation to Inglewood, California. It has its own branch public library and an important shopping center for the area.[36][37] (Also see Inglewood Knolls)

Morningside Park

editMorningside Park is a commercial district in the eastern part of the city. Though the city of Inglewood does not define the district's boundaries, it may be delineated by Hyde Park on the north, Manchester Square on the east, Century Boulevard on the south and Prairie Avenue on the west. The major streets that run through the area are Manchester and Crenshaw boulevards. It is six miles (10 km) from Los Angeles International Airport and about two miles (3 km) from SoFi Stadium, the home of the NFL's Los Angeles Rams and the Los Angeles Chargers. The district is also the location of Kia Forum, an entertainment venue and where for 32 years the NBA's Los Angeles Lakers and NHL's Los Angeles Kings played and The Village at Century shopping center. This neighborhood was once the site of the Hollywood Park Racetrack. It is also the home to three gated-communities called Carlton Square, Briarwood Village & The Renaissance.

North Inglewood and Fairview Heights

editNorth Inglewood is a neighborhood north of the former Santa Fe railroad tracks, where the K Line currently is. In 2009, it was reported to be the site of a "burgeoning arts scene" at East Hyde Park Boulevard and La Brea Avenue.[38] Fairview Heights is a signed area north of Florence and east of La Brea Avenues.

Inglewood Knolls

editSituated in the southeastern corner of the city, Inglewood Knolls is a subdivision of tract homes built in 1953–54. It is bordered by Crenshaw Blvd. on the west, 108th St. on the north, Spinning Ave. on the east, and Imperial Highway on the south. A shopping center on the northeastern quadrant of the intersection of Crenshaw and Imperial was also constructed in the mid-1950s, originally including a Food Giant grocery store, Thrifty Drug, J.J. Newberrys, and Lishon's Music Store, among others. Century Park Elementary School on Spinning Ave., although fully within Inglewood city limits, is actually part of the L.A. school district.

Climate

edit| Climate data for Inglewood, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

97 (36) |

104 (40) |

97 (36) |

98 (37) |

110 (43) |

106 (41) |

101 (38) |

94 (34) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 65.1 (18.4) |

65.3 (18.5) |

65.3 (18.5) |

67.5 (19.7) |

69.2 (20.7) |

71.9 (22.2) |

75.2 (24.0) |

76.3 (24.6) |

76.0 (24.4) |

73.6 (23.1) |

70.3 (21.3) |

66.0 (18.9) |

70.1 (21.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 47.5 (8.6) |

49.0 (9.4) |

50.5 (10.3) |

53.0 (11.7) |

56.4 (13.6) |

59.7 (15.4) |

62.9 (17.2) |

63.8 (17.7) |

62.6 (17.0) |

58.5 (14.7) |

52.4 (11.3) |

47.9 (8.8) |

55.4 (13.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 23 (−5) |

32 (0) |

34 (1) |

39 (4) |

43 (6) |

48 (9) |

49 (9) |

51 (11) |

47 (8) |

41 (5) |

34 (1) |

32 (0) |

23 (−5) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.71 (69) |

3.25 (83) |

1.85 (47) |

0.70 (18) |

0.22 (5.6) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.21 (5.3) |

0.56 (14) |

1.11 (28) |

2.05 (52) |

12.82 (326) |

| Source: [39][40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 1,536 | — | |

| 1920 | 3,286 | 113.9% | |

| 1930 | 19,480 | 492.8% | |

| 1940 | 30,114 | 54.6% | |

| 1950 | 46,185 | 53.4% | |

| 1960 | 63,390 | 37.3% | |

| 1970 | 89,985 | 42.0% | |

| 1980 | 94,162 | 4.6% | |

| 1990 | 109,602 | 16.4% | |

| 2000 | 112,580 | 2.7% | |

| 2010 | 109,673 | −2.6% | |

| 2020 | 107,762 | −1.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[41] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[42] | Pop 2010[43] | Pop 2020[44] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 4,628 | 3,165 | 4,398 | 4.11% | 2.89% | 4.08% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 52,260 | 47,029 | 40,804 | 46.42% | 42.88% | 37.86% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 209 | 220 | 199 | 0.19% | 0.20% | 0.18% |

| Asian (NH) | 1,217 | 1,374 | 2,107 | 1.08% | 1.25% | 1.96% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 345 | 323 | 331 | 0.31% | 0.29% | 0.31% |

| Some other race (NH) | 248 | 345 | 855 | 0.22% | 0.31% | 0.79% |

| Mixed or Multiracial (NH) | 1,844 | 1,768 | 3,391 | 1.64% | 1.61% | 3.15% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 51,829 | 55,449 | 55,677 | 46.04% | 50.56% | 51.67% |

| Total | 112,580 | 109,673 | 107,762 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

editThe 2010 United States Census[45] reported that Inglewood had a population of 109,673. The population density was 12,062.1 inhabitants per square mile (4,657.2/km2). The racial makeup of Inglewood was 50.6% Hispanics or Latinos (of any race),[46] 43.9% African American, 23.3% White (2.9% non-Hispanic White),[46] 0.7% Native American, 1.5% Asian, 26.3% from other races, and 4.1% from two or more races. The Census reported that 98.6% of the population lived in households, 0.9% lived in noninstitutionalized group quarters, and 0.5% were institutionalized.

Of the 36,389 households, 42.1% had children under living in them, 36.0% were married couples living together, 24.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 8.1% had a male householder with no wife present, 6.4% were unmarried partnerships, 0.6% were same-sex partnerships, 25.7% were made up of individuals, and 7.6% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.97. With 25,019 families (68.8% of all households), the average family size was 3.59.

The age distribution was 26.7% under 18, 10.8% from 18 to 24, 28.9% from 25 to 44, 24.3% from 45 to 64, and 9.4% who were 65 or older. The median age was 33.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.6 males. For every 100 females 18 and over, there were 86.8 males.

The 38,429 housing units had an average density of 4,226.5/sq mi (1,631.9/km2), of which 37.0% were owner-occupied and 63.0% were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.5%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.5%, while 39.2% of the population lived in owner-occupied housing units and 59.4% lived in rental housing units.

According to the 2010 United States Census, Inglewood had a median household income of $43,394, with 22.4% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[46]

Mapping L.A.

editMexican and Salvadoran are the common ancestries in Inglewood. Mexico and El Salvador were the most common foreign places of birth in the 2000 census.[47]

In 2009, the Los Angeles Times's "Mapping L.A." project supplied these neighborhood statistics based on the 2000 census.[48]

The population was 112,482, or 12,330 people per square mile, among the highest densities for the South Bay and among the highest densities for the county. The percentage of African Americans was high for the county, and the population was moderately diverse. Median household income was $46,574, low for both the South Bay and for the county. The median age was 29, young for the county; the percentage of residents aged 10 or under was among the county's highest. Three people, on the average, lived in each household – high for the South Bay but about average for the county. There was a higher percentage of families headed by single parents than elsewhere in the county. The percentage of veterans who served during 1975–89 and 1990–99 was among the county's highest.

| Inglewood and nearby areas |

Inglewood[48] | Hyde Park[49] | Ladera Heights[50] |

Westchester[51] | Hawthorne[52] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 112,482 | 38,635 | 6,509 | 41,500 | 86,265 |

| White | 5% | 5% | 19% | 52% | 13% |

| Latino | 46% | 27% | 3% | 17% | 44% |

| Asian | 3% | 2% | 4% | 10% | 8% |

| Black | 46% | 66% | 71% | 19% | 32% |

| Household income | $46,574 | $39,460 | $117,925 | $77,473 | $43,602 |

| College degree | 13% | 13% | 53% | 42% | 13% |

| Median age | 29 | 31 | 43 | 35 | 27 |

| Single parents | 25% | 29% | 10% | 15% | 27% |

| Veteran | 8% | 9% | 13% | 9% | 7% |

| Foreign born | 30% | 20% | 7% | 21% | 33% |

| Where? | Mexico, El Salvador |

Mexico, El Salvador |

Trinidad, Canada |

Mexico, Philippines |

Mexico, Guatemala |

| Ethnic diversity (*) | Moderate .571 | Moderate .488 | Moderate .446 | High .660 | High .676 |

| Home ownership | 36% | 47% | 77% | 52% | 26% |

(*) "The diversity index measures the probability that any two residents, chosen at random, would be of different ethnicities. If all residents are of the same ethnic group it's zero. If half are from one group and half from another it's .50."[53]

Homelessness

editIn 2022, Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority's Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count counted 751 homeless individuals in Inglewood.[54]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 513 | — |

| 2017 | 349 | −32.0% |

| 2018 | 542 | +55.3% |

| 2019 | 470 | −13.3% |

| 2020 | 525 | +11.7% |

| 2022 | 751 | +43.0% |

| Source: Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority | ||

Arts and culture

editLandmarks

editThe Forum was built in 1967 and designed by architect Charles Luckman, who also designed Madison Square Garden.[55] The Forum was intended to evoke the Roman Forum in Rome.[56] For decades, the Forum was one of LA's biggest concert venues; Elvis Presley, Led Zeppelin and the Jackson 5 were among the superstars to headline the arena.[57] The Forum also achieved its greatest fame as the home of the NBA's Los Angeles Lakers and the NHL's Los Angeles Kings. In 1999, both teams moved to the Staples Center and the Forum was sold to the Faithful Central Bible Church, which used it for Sunday services and rented it out for concerts or sporting events.[58] In 2012, the Forum was purchased by The Madison Square Garden Company, owners of New York's Madison Square Garden, for $23.5 million; MSG announced plans to spend $50 million to refurbish and renovate the arena for use as a "world-class" concert venue.[59] The "Fabulous" Forum presented by Chase reopened on January 15, 2014, with the first of six historic performances by the Eagles.[60] The reinvention of the Forum has created the largest indoor performance venue in the country designed with a focus on music and entertainment.[55] On April 4, 2022, "The Forum" was renamed "Kia Forum" due to a naming rights deal between Steve Ballmer, the owner of The Forum, and car manufacturer Kia.[61]

On February 24, 2015, the Inglewood City Council approved plans for the construction of an NFL-capacity stadium, later named SoFi Stadium, with a 5–0 unanimous vote to combine the 60-acre (24 ha) plot of land with the larger Hollywood Park development and rezone the area to include Sports/Entertainment capabilities. 6 acres (2.4 ha) of Hollywood Park were devoted to Lake Park, a naturally-replenishing water feature which is claimed to recycle 26 million gallons of water annually.[62] This cleared the way for developers to begin construction on the venue as planned in December 2015.[63][64][65] On January 13, 2016, one day after the NFL approved of the Rams return to Los Angeles, construction began on the Inglewood site.[66] SoFi Stadium opened in 2020.

Public libraries

editThe City of Inglewood operates a main library in the city's Civic Center, in addition to a branch in the southeastern corner of the city, near the intersection of Crenshaw and Imperial.[67]

Symphony

editThe Southeast Symphony Association is a non-profit, musical and cultural association in Inglewood, founded in 1948 to create an orchestra that welcomes African-American musicians.[68]

Open Studios

editThe annual Open Studios event features "drawing, painting, photography and more", organized by a volunteer group of artists with support by the Inglewood Cultural Arts, Inc. (ICA) organization. The first year of the event saw six artists featured, but at the November 2011 event "more than 30" were expected, said Renee Fox, gallery director at the Beacon Arts Building on North La Brea Avenue. The structure has been turned into 14 artists' studios, with 16 more to be added by the end of 2011. A nearby former auto showroom has also been turned over to artists.[69]

Sports

editProfessional sports

editInglewood is home to the Los Angeles Rams and Los Angeles Chargers of the National Football League who play at SoFi Stadium. The stadium hosted Super Bowl LVI in 2022,[70] and will host Super Bowl LXI in 2027.[71] The Los Angeles Lakers and Los Angeles Kings played their home games at Kia Forum from 1967 to 1999, until the completion of Crypto.com Arena in Downtown Los Angeles.

On July 26, 2019, the Los Angeles Clippers announced plans to build a new arena and entertainment center in Inglewood.[72] The announcement explained that the new arena would be completed at the same time their current leasing agreement with Crypto.com Arena is set to expire. The privately financed project includes the arena, the team's business and basketball offices, training facility, community and retail spaces. Weeks later, on September 10, 2019, Clippers owner Steve Ballmer announced plans to invest $100 million into the city of Inglewood as part of the arena deal.[73] The investment includes $80 million for affordable housing, assistance to renters and first-time homebuyers. Another $12.75 million will be invested into school and youth programs. The arena opened in August 2024.

| Club | League | Venue | Founded | Established in Inglewood |

Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles Rams | National Football League | SoFi Stadium | 1936 (in Cleveland) | (2020 in Inglewood) | 4 (1 in Inglewood) (1 in Los Angeles Pre-1970 AFL–NFL merger) |

| Los Angeles Chargers | 1960 (in Los Angeles) | (2020 in Inglewood) | 1 (AFL Championship) | ||

| Los Angeles Clippers | National Basketball Association | Intuit Dome | 1970 (As the Buffalo Braves) | (1984 in Los Angeles, 2024 in Inglewood) | 0 |

Former Teams

editInglewood was the former home of the Los Angeles Lakers of the NBA and of the Los Angeles Kings of the NHL from 1967 to 1999, as well as the Los Angeles Sparks of the WNBA from 1997 to 2000. All teams moved to Crypto.com Arena for the following seasons.

| Club | League | Venue | Founded | Established in Inglewood |

Departed Inglewood |

Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles Lakers | National Basketball Association | Kia Forum | 1947 (in Minneapolis) | (1967 in Inglewood) | 1999 | 17 (6 in Inglewood) (5 in Minneapolis, 6 after departure from Inglewood) |

| Los Angeles Kings | National Hockey League | Kia Forum | 1967 | (1967 in Inglewood) | 1999 | 2 (2 after departure from Inglewood) |

| Los Angeles Sparks | Women's National Basketball Association | Kia Forum | 1997 | (1997 in Inglewood) | 2000 | 3 (3 after departure from Inglewood) |

Olympic and Paralympic Games

editAt the 1984 Summer Olympics, The Forum hosted the basketball competition and the men's handball final.[74] During the 2028 Summer Olympics, the opening and closing ceremonies will be held at SoFi Stadium, which will also host the swimming events.[75] Archery will be held in Lake Park adjacent to the stadium. Intuit Dome will host all the basketball events during the games.[76]

2026 FIFA World Cup

editSoFi Stadium will host several matches during the 2026 FIFA World Cup, which will be held across the US, Canada, and Mexico.[77]

Government

editMunicipal

editThe City of Inglewood has a council–city manager type of government. The mayor is an elected office and is the chief executive officer, but in all other regards is an equal member of the city council.

The current mayor of Inglewood is James T. Butts Jr. who took office after unseating Daniel K. Tabor who completed the term of Roosevelt Dorn.

The Inglewood Police Department is the city's police department. Since the Inglewood Fire Department was disbanded in 2000, the city contracts its fire service with the Los Angeles County Fire Department.[78]

Federal representation

editIn the United States House of Representatives, Inglewood is split between California's 37th congressional district, represented by Democrat Sydney Kamlager-Dove, and California's 43rd congressional district, represented by Democrat Maxine Waters.[79]

State representation

editIn the California State Legislature, Inglewood is in the 35th Senate District, represented by Democrat Laura Richardson, and in the 62nd Assembly District, represented by Democrat Jose Solache.[80]

Los Angeles County

editInglewood is part of Los Angeles County, for which the Government of Los Angeles County is defined and authorized under the California Constitution, California law, and the Charter of the County of Los Angeles.[81] The county government is primarily composed of the elected five-member Board of Supervisors, other elected offices including the Sheriff, District Attorney, and Assessor, and numerous county departments and entities under the supervision of the chief executive officer.

Regional

editThe city is a member of the South Bay Cities Council of Governments.[82]

Politics

editInglewood has the highest percentage of registered Democrats of any city in California, with 75.6 percent of its 48,615 voters registered in May 2009 as Democrats. Seven percent were registered as Republicans, and 14.1 percent declined to state a preference.[83]

In 2005, the Bay Area Center for Voting Research, a nonpartisan organization in Berkeley, ranked Inglewood as the sixth-most-liberal city in the United States, after Oakland, California, and just ahead of Newark, New Jersey. Researchers examined voting patterns of 237 American cities with populations over 100,000 and ranked them on liberal and conservative scales.[84]

In the past three decades, the presidential candidates nominated by the Democratic Party have all carried Inglewood with over 80% of the vote. The last seven elections results are listed below:

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020[85] | 88.62% 41,124 | 9.56% 4,437 | 1.82% 846 |

| 2016[85] | 91.13% 35,217 | 5.23% 2,020 | 3.65% 1,409 |

| 2012[86] | 93.82% 34,795 | 5.06% 1,877 | 1.12% 415 |

| 2008[87] | 92.78% 35,962 | 6.04% 2,325 | 1.17% 452 |

| 2004[88] | 87.45% 28,391 | 11.85% 3,847 | 0.71% 229 |

| 2000[89] | 91.16% 22,076 | 7.01% 1,698 | 1.83% 444 |

| 1996[90] | 89.00% 22,656 | 7.17% 1,825 | 3.83% 974 |

| 1992[91] | 82.26% 23,778 | 9.81% 2,837 | 7.92% 2,290 |

Education

editPublic and private schools

editMost of Inglewood is served by the Inglewood Unified School District. The district has two zoned high schools, Inglewood High School, Morningside High School, City Honors High School and an alternative high school, Inglewood Continuation High School (formerly Hillcrest Continuation High School).

Some of it is zoned in the Los Angeles Unified School District. LAUSD operates one school in the Inglewood city limits, Century Park Elementary.[92][93]

When the Inglewood Union High School District, now known as the Centinela Valley Union High School District, opened in 1905, the Inglewood School District, then only operating primary schools, was within the high school district. The Centinela Valley district received its current name on November 1, 1944. On July 1, 1954, the Inglewood elementary school district withdrew from the Centinela Valley district, becoming a unified school district.[94]

Public charter schools include:

- Ánimo Inglewood Charter High School of Green Dot Public Schools[95]

- Ánimo Leadership Charter High School of Green Dot[96]

Private schools include:

- St. John Chrysostom Elementary School is a private Catholic school.

- St. Mary's Academy, "In 1966 St. Mary's Academy left its home of many years on Slauson Avenue [at Crenshaw Boulevard] in Los Angeles for a new building on Grace Avenue across from [Daniel] Freeman Hospital".[8]: 62

- Good Shepherd Lutheran School, 1936–2003

Schools history

editIn 1888, a school district was organized, trustees were elected and a building was chosen. The school opened on May 21 that year on the second floor of a livery stable on Grevillea Avenue between Regent Street and Orchard (today's Florence Avenue), with 17 boys and 16 girls. The first teacher was Minnie Walker, a graduate of Los Angeles State Normal School. The schoolroom, named Bucephalus Hall, after a horse belonging to town founder Daniel Freeman, was also used for community meetings.[8]: 6

Meanwhile, a permanent school building was erected on Grevillea Avenue a block to the south, between Regent and Queen. It remained Inglewood's only school until 1911. It was destroyed by an earthquake in 1920.[8]: 6 and 26

The Centinela Valley Union High School District was organized in 1904 to bring secondary education to the town. Inglewood High opened in two rooms of the school building with 15 students taught by Nina Martin, principal, and Anna McClelland. Four years later, a new building rose on 9.5 acres (3.8 ha) of land, and the first graduation of one boy and four girls took place in 1908.[8]: 13–14 Until 1912 there was a new principal every year at the grammar school, but on May 8 of that year George W. Crozier was named principal, and he held the post for 20 years. The school was renamed in his honor in 1932.[8]: 20 In 1913, George M. Green was appointed principal of Inglewood Union High School; he retired from that position in 1939.[8]: 22

In 1914, voters approved bonds for high school improvement. Four more buildings and a power plant were erected, "joined by walks and arcades." The improvement included a "five-room model flat in the Home Economics Building." Nine acres of land were bought at Kelso Avenue and Damask (now Inglewood Avenue) for an experimental agricultural statement, thenceforth known as "The Farm." There were gardens, an orchard and an alfalfa field. In 1915 Inglewood High won a first-place Los Angeles County prize for its beautiful ivy-covered brick buildings.[8]: 24 These buildings were destroyed in 1953 to make room for new ones.[8]: unpaged [58c]

In the mid-1920s, the high school district stretched all the way south to El Segundo, so two women teachers were asked to live in El Segundo and ride the school buses with the students every day to and from that city – for an extra dollar a day in pay. In 1923 girls adopted a school uniform, "a dark blue skirt with a white middy."[8]: 30

In 1925 a new fine arts building for the high school was erected on the southwest corner of Grevillea and Manchester, replacing the Truax Candy Kitchen,[8]: 34 but it was severely damaged by the Long Beach earthquake of 1933. It was "later rebuilt with WPA help but lost its magnificent stairway and all its fireplaces." Temporary classrooms were built on Olive Street, "all too cold in winter and too hot most of the time."[8]: 41

The athletic field on the west side of the campus, later called Badenoch Field, was used for physical education and sporting events. In 1937, agricultural classes were ended at the Farm and Sentinel Field was dedicated there for sports activities.[8]: 30 By 1938 there were more than 3,000 students and 141 teachers at the high school.[8]: 43

The "startling news" of 1948 was the dismissal "of the entire administrative staff at Inglewood High School, beginning with Principal James R. Haines." He was replaced by Forrest Murdoch of Everett, Washington, as superintendent and Fred Heisner as principal.[8]: 49

In 1952, another secondary school campus in Inglewood was opened in the east side neighborhood of Lockhaven as Morningside High School.[8]: 55 Center Park School of Los Angeles became part of the Inglewood School District in 1961 when its area (Crenshaw-Imperial) was annexed to the city.[8]: 59 In the 1970s, its name was changed to Worthington School to honor Frances and William Worthington.[8]: 74

Media

editHollywood Park is the home of NFL Media which consists of NFL Network, NFL RedZone, NFL.com, and the NFL app. Formerly located in Culver City, the NFL Los Angeles campus is located adjacent to Sofi Stadium.[97][98]

TV network Showtime also has offices in Inglewood, adjacent to LAX and Interstate 405.[99]

Newspapers

edit- The Morningside Park Chronicle, Inglewood News and Inglewood Today circulate in the city.[100][101][102][103][104]

- Inglewood Daily News, defunct

Filming locations

editInglewood has been in several motion picture movies and television shows such as:

- Inglewood City Hall (1 Manchester Boulevard): The interior of City Hall was the fictional IADC (Inter-Agency Defense Command) Headquarters for The New Adventures of Wonder Woman and also the coroner's office in Jack Klugman's 1970s television drama series Quincy, M.E.[105]

- The city was a filming location for The Wood, a 1999 movie about three African-American men recalling their childhood in 1980s Inglewood.[106]

- The 2015 film Dope is set in the Darby-Dixon neighborhood (nicknamed "The Bottoms") of Inglewood.[107]

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editStreets and highways

editA "grand avenue at least 150 feet wide" was being built in late 1887 from the end of Figueroa Street in Los Angeles "to the new town of Inglewood on the Centinela ranch", to be "planted with a border of tropical trees, making it one of the handsomest five-mile drives" on the coast."[108][109]

Major streets that run through Inglewood are La Cienega Boulevard, Crenshaw Boulevard, Hawthorne Boulevard (California), La Brea Avenue, Century Boulevard, Imperial Highway, Manchester Avenue, (Manchester Boulevard in Inglewood), Florence Avenue, and Prairie Avenue.

There are 2 freeways that serve the city, Interstate 405 and Interstate 105 (California). Interstate 110 is located nearby South Los Angeles.

Public transportation

editThe city is served by the K Line of the Los Angeles Metro Rail system. There are 3 stations located in the city, Fairview Heights, Downtown Inglewood, and Westchester/Veterans station. The south side of the city is served by the nearby C Line, which the Crenshaw and Hawthorne/Lennox stations are located nearby. The city is planning the Inglewood Transit Connector, an automated people mover that will connect the city's sports and entertainment venues to the forthcoming downtown rail station.[110]

A $3,000 train station, described as a "natty and attractive building", was constructed in 1887 at the temporary end of the Ballona railroad line outward bound from Los Angeles. The tracks were to continue west through the Centinela ranch to the ocean.[108][111][112]

The 18.03-mile line (29.02 km) was opened for business on September 7, 1887, with stops (from northeast to southwest) at Ballona Junction, Nadeau Park, Baldwin, Slauson, Wildeson, Hyde Park, Inglewood, Danville, Mesmer, and Port Ballona. A train left Los Angeles at 9:15 a.m. on the one-hour journey and returned from Port Ballona at 4 p.m.[113]

In that year the Los Angeles Herald noted that Inglewood was "at the junction of two railroads, one branch going to Ballona Harbor and the other to the beautiful seaside resort, Redondo Beach. . . . Two trains a day now pass Inglewood station."[114]

The Centinela-Inglewood Company used a four-horse coach to bring prospective buyers from Los Angeles, leaving at 9:30 a.m. and returning at 2 p.m. Being planned were "frequent fast trains between Los Angeles and Inglewood over the California Southern Railroad.[13]

Fire

editFire protection is provided by the Los Angeles County Fire Department stations 18, 170, 171, 172, and 173.

Health

editThe Los Angeles County Department of Health Services operates the Curtis Tucker Health Center in Inglewood.[116] The city was served by the Daniel Freeman Memorial Hospital for more than five decades, from 1954 until its closure in 2007. Inglewood is still served and the home to Centinela Hospital Medical Center.

Notable people

editBorn in Inglewood

edit- 310babii, rapper[117]

- Hassan Adams, NBA player[118]

- Cornell Armstrong, NFL cornerback[119]

- Don August, baseball player[120]

- Tyra Banks, fashion model, television personality, talk show host and actress[121][122]

- Maybelle Blair (born 1927), All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player[123]

- Jason Aalon Butler, musician and political activist[124]

- Erica Campbell, American gospel singer, songwriter, musician, and First Lady

- Tina Campbell, American gospel singer and musician

- Shawn Chrystopher, recording artist, producer[125]

- Dottie Wiltse Collins, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player[126]

- Todd Davis, NFL player[127]

- Mark Eaton, NBA basketball player[128]

- Scott Eyre, baseball player[129]

- Becky G, actress and singer[130]

- Patricia Peck Gossel, medical historian and curator[131]

- Erick Green, basketball player[132]

- Tanedra Howard, actress[133]

- Flo Hyman, volleyball player[134]

- Vicki Lawrence,[135] actress and comedian

- Swae Lee, rapper[136]

- Jim Lefebvre, MLB player and manager[137]

- Mack 10, rapper[138]

- Tanjareen Martin, actress[139]

- Philip "Bishop Lamont" Martin, rapper[140]

- Len Maxwell, voice actor and announcer[141]

- Scott McGregor, baseball player[142]

- Lisa Moretti, wrestler[143]

- Valerie Ogoke, basketball player[144]

- Jeff Franklin, director and producer[145]

- Omarion, R&B singer, songwriter, dancer and actor[146]

- Marcel Reece, NFL player[147]

- Brittney Reese, Olympic and World champion in long jump[148]

- Sabi, singer-songwriter and dancer[149]

- Steve Saleen, founder of Saleen and racing driver[150]

- Jamal Sampson, NBA player[151]

- Donald Sanford, American-Israeli Olympic sprinter[152]

- Shade Sheist, recording artist, singer-songwriter, actor[153]

- Zoot Sims[154] jazz saxophonist

- SiR, singer[155]

- Craig Smith, NBA player[156]

- D Smoke, musician[157]

- Bishop Jaime Soto of the Diocese of Sacramento[158]

- Chris Strait, comedian[159]

- Esther Williams, swimmer and motion picture actress[160]

- Fani Willis, district attorney of Fulton County, Georgia[161]

- Brian Wilson, musician, singer, songwriter, and record producer[162]

- Jose Villarreal, soccer player[163]

- Cameron Young (born 1996), basketball player for Hapoel Haifa of the Israeli Basketball Premier League

Other residents

edit- Salvatore (Sonny) Bono, singer, actor, and congressman[164]

- Jeanne Crain, actress[165][166]

- Chris Emile, dancer[167]

- Daniel Freeman, credited as the founder of Inglewood[168]

- Cali Swag District, hip hop group[169]

- Lisa Leslie, retired WNBA basketball player[170]

- Don Megowan, actor[171]

- Damani Nkosi, rapper[172]

- Frank D. Parent, municipal court judge[173]

- Paul Pierce, retired NBA basketball player[174][175]

- Cindy Sheehan, American anti-war activist[176]

- Skeme (Lonnie Kimble), rapper[177]

- Chastin West, football player[178]

- Chalino Sanchez, singer

Sister cities

editInglewood is affiliated with the following sister cities

- Bo, Sierra Leone[179]

- Pedavena Veneto, Italy[180]

- Port Antonio, Jamaica[181]

- Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

- Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico[182]

See also

edit- Los Angeles Times suburban sections, for a time capsule placed in the Inglewood City Hall

- List of cities and towns in California

- Largest cities in Southern California

References

edit- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Inglewood". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Inglewood (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ "ZIP Code(tm) Lookup". United States Postal Service. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "Home". Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "City History". City of Inglewood. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Waddingham, Gladys (1994). The History of Inglewood. Inglewood: The Historical Society of Centinela Valley.

- ^ "Inglewood: 8 Things You Didn't Know About The Neighborhood's History". L.A. Taco. December 8, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ "Things To Do in Los Angeles". LAOkay.com.

- ^ "City of Inglewood : Departments". Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Waddingham used the spelling Ignacio for both Avila and Machado.

- ^ a b "Briefs". Los Angeles Times. December 11, 1887. p. 5 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Inglewood Park Cemetery: Living Heritage". Inglewood Park Cemetery. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Hollywood Park: About". Hollywood Park. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009.

- ^ Goodbye to the glory days of California horse racing – The Guardian, Daniel Ross, September 30, 2013

- ^ "Fosters Freeze: Company History". Fosters Freeze. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- ^ "Past Winners of the All-America City Award". National Civic League. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ^ "Ex-Klan Chief Dies After Traffic Row; Knife Fight With Truck Driver Following Collision Proves Fatal for Gus Price, 64". Los Angeles Times. May 21, 1949. ProQuest 165934474.

- ^ "Airplane Circus at Glendale to Start New Line". Los Angeles Times. October 13, 1931. ProQuest 162478024.

- ^ Max M. Kampelman, The Communist Party vs. the CIO: A Study in Power Politics (1957) pp. 25-27.

- ^ Robert H. Zieger, The CIO: 1935-1955 (1995) pp 128-130.

- ^ John Barnard, American Vanguard: The United Auto Workers During the Reuther Years, 1935–1970 (2004) pp 173-176.

- ^ a b "Parents Lose Plea in Inglewood Suit". Los Angeles Times. September 2, 1970. p. D-2.

- ^ "Inglewood Order". Los Angeles Times. July 26, 1970. p. F-5.

- ^ "Negro Elected to Inglewood Public Office". Los Angeles Times. April 7, 1971. p. 18. ProQuest 156655639.

- ^ Greene, Nick (November 3, 2010). "Tabor cruises to win in Inglewood mayoral race". San Gabriel Valley Tribune.

- ^ Janet-Rae Dupree (February 28, 1991). "Census Shows Influx of Asians on Peninsula". Los Angeles Times. p. 3. ProQuest 281324756.

- ^ "American FactFinder – Community Facts". factfinder.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "American FactFinder – Community Facts". factfinder.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Hugo Martin (October 9, 2000). "Latino Revolution Leaves Some City Councils Untouched". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. ProQuest 421693560.

- ^ "Inglewood Churches and Religion (Inglewood, California)". areaConnect. MDNH, Inc.

- ^ Christensen, Kim (February 9, 2018). "Inglewood mayor's role in $100-million trash hauling pact is questioned". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Table 2. Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2011". 2011 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. April 2012. Archived from the original (CSV) on January 17, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Anne Cheek La Rose (May 31, 2013). "What's in an Inglewood name?". The Morningside Park Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ "City of Inglewood: Departments – Library". City of Inglewood. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- ^ "Crenshaw Imperial Shopping Center (includes a map)". LoopNet. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- ^ Alejandro Lazo (November 16, 2009). "Inglewood art studio tour a stroke of genius". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Inglewood, California Travel Weather Averages". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Inglewood, California (90301) Climate Normals". Weatherforyou.com. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Inglewood, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Inglewood, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Inglewood, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – Inglewood city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Inglewood (city) QuickFacts". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ "Inglewood". Maps.latimes.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ a b ""Inglewood" entry on the Los Angeles Times "Mapping L.A." website". Projects.latimes.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ ""Hyde Park" entry on the Los Angeles Times "Mapping L.A." website". Projects.latimes.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ ""Ladera Heights" entry on the Los Angeles Times "Mapping L.A." website". Projects.latimes.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ ""Westchester" entry on the Los Angeles Times "Mapping L.A." website". Projects.latimes.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ ""La Crescenta-Montrose" entry on the Los Angeles Times "Mapping L.A." website". Projects.latimes.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ Definition of "diversity index" from Mapping L.A. The most diverse area is Mid-Wilshire, and the least diverse is East Los Angeles. Projects.latimes.com

- ^ "Homeless Count by City/Community". LAHSA. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Forum." The Forum. The Madison Square Garden Company, n.d. Web. March 31, 2015.

- ^ "The Forum". Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ "Renovated Forum Arena Brings Class and Competition to L.A. Concert Scene." Speakeasy RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. March 29, 2015.

- ^ Kudler, Adrian Glick. "Come Tour The Renovated And Revitalized Inglewood Forum." Curbed LA. N.p., January 15, 2014. Web. March 29, 2015.

- ^ Vincent, Roger (June 26, 2012). "Forum owners plan to revive venue with $50-million renovation". LA Times. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "The Forum." The Forum. The Madison Square Garden Company, n.d. Web. March 29, 2015.

- ^ News Staff, CBSLA (April 4, 2022). "The Forum in Inglewood officially renamed 'Kia Forum'". Cbsnews.com. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ "Watch: Architect explains how SoFi Stadium's lake recycles 26 million gallons of water". Msn.com. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Inglewood Council Rams Through NFL Stadium Proposal | NBC Southern California". Nbclosangeles.com. February 25, 2015. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ "Inglewood unanimously approves stadium plan at Hollywood Park | ProFootballTalk". Profootballtalk.nbcsports.com. February 25, 2015. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ Tim Logan; Angel Jennings; Nathan Fenno (February 24, 2015). "Inglewood council approves NFL stadium plan amid big community support". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Marc Cota-Robles (January 13, 2016). "CONSTRUCTION UNDERWAY AT SITE OF LOS ANGELES RAMS' NEW HOME IN INGLEWOOD". ABC7.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Library". City of Inglewood. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ "The Southeast Symphony". Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ Barbara Thornburg (November 5, 2011). "Open Studios Blossoms With Promise". Los Angeles Times. p. E-2.

- ^ "Where will the Super Bowl be played for the next five years?". NBC Sports Washington. May 28, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (December 13, 2023). "Super Bowl expected to return to SoFi in 2027: Los Angeles area to host big game for second time since 2022". CBS Sports. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Los Angeles Clippers announce plans for new arena and entertainment center in Inglewood". CBS Sports. July 26, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ "Clips' arena deal to include $100M for Inglewood". ESPN.com. September 10, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ 1984 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. Part 1. pp. 102–4

- ^ Merola, Lauren; Cooper, Mark. "LA28 unveils venue plan: Swimming in SoFi, softball in Oklahoma City". The Athletic. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 21, 2024. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Golliver, Ben (January 17, 2024). "Clippers' Intuit Dome will host 2026 NBA All-Star Game, 2028 Olympics". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 27, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Los Angeles County Fire Department". 5280fire.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ "Communities of Interest – City". California Citizens Redistricting Commission. Archived from the original on September 30, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ California Government Code § 23004

- ^ "Livable Communities Mtg Nov 22 Cancelled – South Bay Cities Council of Governments". Southbaycities.org. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Report of Registration as of May 4, 2009 – Registration by Political Subdivision by County" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ "Study Ranks America's Most Liberal and Conservative Cities". Govpro.com. August 16, 2005. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "Supplement to the Statement of Vote – Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF). Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote – Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF).

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote – Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF).

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote – Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF).

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote – Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF).

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote – Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF).

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote" (PDF).

- ^ " "Century Park EL". Los Angeles Unified School District. Archived from the original on September 5, 2013.

- ^ "Local District 8" (PDF). Los Angeles Unified School District. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "History and Profile". Centinela Valley Union High School District. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014.

- ^ "Home". Ànimo Inglewood Charter High School. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". Ánimo Leadership Charter High School. Archived from the original on January 25, 2011.

- ^ "NFL Media Inglewood". The Real Deal Los Angeles. March 28, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ "NFL Los Angeles Officially Opens". nflcommunications.com. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ "Showtime Networks Grabs Space in Inglewood, California, in Latest High-Profile Entertainment Deal". CoStar. March 28, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ 医療レーザー脱毛と抑毛ローションの良いところを比較しよう. Morningsideparkchronicle.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "The Inglewood News El Segundo CA, 90245". Manta.com. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ "Inglewood Today". Inglewoodtodaynews.com. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Newsflash: Inglewood Matters!". Kcet.org. January 24, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ "Does the Crenshaw Subway Coalition Have Enough Juice to Alter Metro's Crenshaw Plans Again? - Streetsblog Los Angeles". La.streetsblog.org. June 28, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ "TV Locations Inglewood City Hall". TVLocations. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008.

- ^ "Plot summary for The Wood". IMDb.

- ^ Blaustein, David (June 19, 2015). "Movie Review: 'Dope' Reveals Itself to be Part Spike Lee, Part John Hughes". Good Morning America. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Notable Purchases". Los Angeles Herald. August 7, 1887. p. 1.

- ^ "A $400,000 Deal". Los Angeles Times. August 7, 1887. p. 2.

- ^ "Everything you need to know about Metro's new K Line".

- ^ "New Buildings". Los Angeles Herald. August 12, 1887. p. 10.

- ^ "Inglewood—New Places Grow in Southern California". Los Angeles Herald. February 10, 1889. p. 4.

- ^ "Opening of the Ballona Branch". Los Angeles Herald. September 8, 1887. p. 10.

- ^ "Splendid Enterprise". Los Angeles Herald. September 11, 1887. p. 3.

- ^ Matthews, Carol (May 13, 2019). "Post Office - Inglewood CA". Living New Deal. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ "Curtis Tucker Health Center." Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ "310Babii Heats Up the L.A. Rap Scene with the Release of 310Degrees".

- ^ "Hassan Adams". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ "Cornell Armstrong". OSDB. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ "Don August Baseball Stats by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Tyra Banks: Snapshot". People Magazine.

- ^ "Tyra Banks". IMDb. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "All-American Girls Professional Baseball League". Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ^ De Gallier, Thea (July 26, 2016). "The Road to Freedom or The Story Behind letlive.'s 'If I'm The Devil...'". Vice Media. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Gerrick. "Inglewood rapper Shawn Chrystopher not hung up on any label deal: 'I'm happy where I am'". LA Times. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Dorothy Collins". AAGPBL. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- ^ "Todd Davis". NFL. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "Mark Eaton, Shot-Blocking Star for the Utah Jazz, Dies at 64". New York Times. May 30, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "Scott Eyre Baseball Stats by Baseball Almanac". baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Becky G dreams of being the next Jennifer Lopez". Los Angeles Times. August 19, 2013.

- ^ "Obituaries: Patricia Peck Gossel, Museum Curator" Washington Post (June 24, 2004): B06.

- ^ "Jazz Sign Erick Green to a Second 10-Day Contract". NBA. February 5, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "Tanedra Howard: A Dream Deferred No More". Archived from the original on March 9, 2010. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Flo Hyman". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009.

- ^ "Vicki Lawrence profile". Richard De La Font Agency. Archived from the original on May 4, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ "Swae Lee, 1993-". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "Jim Lefebvre Baseball Stats by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Mack 10 at IMDb

- ^ "Tanjareen Martin – TV.com". February 4, 2013. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- ^ "Interview with Bishop Lamont". Aftermath Music. January 2006. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007.

- ^ Len Maxwell at IMDb

- ^ "Scott McGregor Baseball Stats". Baseball Almanac.

- ^ Lisa Moretti at IMDb

- ^ "2006=07 Women's basketball Roster: 34 Valerie Ogoke". lmulions.com. Loyola Marymount University. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ Flemming, Jack (January 21, 2022). "'Full House' creator Jeff Franklin wants $85 million for mansion on Manson murder land". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "Omarion – Biography". Billboard.

- ^ "Behind the Shield: Online October 12th". Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Brittney Reese hopes to be leaps and bounds above the rest". Los Angeles Times. April 20, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

Reese, who was born in Inglewood, California, and moved at the age of 3 to Mississippi

- ^ "Sabi". HotNewHipHop. November 6, 2013.

- ^ Bengali, Shashank (August 13, 2020). "Fraud charges, lost patents: How an L.A. auto legend's China venture crashed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "Jamal Sampson". ESPN.com. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Olympics / Profile / Proud to Run for His Adopted Country". TheMarker. July 9, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2017 – via Haaretz.

- ^ Henderson, Alex (2002). "Shade Sheist > Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ "Zoot Sims". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Kellman, Andy. "SiR Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Craig Smith Stats". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Crumpton, Taylor (November 14, 2019). "Meet D Smoke, Inglewood And Hip-Hop's Next Hometown Hero". Vibe. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Bishop Jaime Soto becomes new head of Diocese of Sacramento". Catholic News Agency. December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Chris Strait". IMDb. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Actress Esther Williams Hospitalized". ABClocal.go.com. Associated Press. October 25, 2006. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2010. While some references cited 1922 as her year of birth, Williams told The Associated Press in 2004 that she was born August 8, 1921.

- ^ Binelli, Mark (February 2, 2023). "Fani Willis Took On Atlanta's Gangs. Now She May Be Coming For Trump". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: the true story of the Beach Boys. New York: New American Library. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-306-80647-6.

- ^ "Jose Villarreal". LA Galaxy. Retrieved December 22, 2024.

- ^ Yates, Nona (January 7, 1998). "Sonny Bono, a Chronology". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Jeanne Crain – Biography and Filmography – 1925". hollywood.com. July 9, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Celebrity Schools". Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ Easter, Makeda (March 7, 2020). "Dance Audiences are Usually Wealthy and White, Chris Emile Aims to Change That". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ "Inglewood—How Places Grow in Southern California". Los Angeles Herald. February 10, 1899. image 4.

- ^ Nadeska Alexis, "Cali Swag District Bring the Party Back to Inglewood" The Boombox, June 1, 2010

- ^ Shelley Smith (February 19, 1990). "She Was Truckin'". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010.

- ^ Don Megowan (1922–1981) at IMDb

- ^ Wendy Geller (March 6, 2014). "Rapper Damani Nkosi Pairs With Musiq Soulchild for New Video". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 26, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "F. D. Parent, Retired City Judge, Dies at 81 :Inglewood Man, Who Served on Bench 28 Years, Coached Eisenhower in High School". Los Angeles Times. June 20, 1960. p. B1. ProQuest 446603572. "Same article". ProQuest 167612861.

- ^ Kamenetzky, Brian (June 2, 2010). "Boston Celtics Paul Pierce talks about Los Angeles Lakers fans". Los Angeles: ESPN. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ^ Billy Witz (June 10, 2008). "Pierce's Road From Inglewood Could Hit Its Summit Nearby". The New York Times.

- ^ Kathlyn Gay (December 31, 2011). American Dissidents: An Encyclopedia of Activists, Subversives, and Prisoners of Conscience: An Encyclopedia of Activists, Subversives, and Prisoners of Conscience. ABC-CLIO. p. 551. ISBN 978-1-59884-765-9. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Bruce (November 5, 2013). "Skeme Reflects On West Coast Unity & Being Influenced By Dolla | Rappers Talk Hip Hop Beef & Old School Hip Hop". HipHop DX. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015.

- ^ "Green Bay Packers: Chastin West". Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Jon Garcia (June 2, 1994). "Officials Study Finances of Sister-City Panel". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Marc Lacey (September 24, 1989). "Inglewood, Jamaican City Plan to Become 'Sisters'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Inglewood Aids City in Jamaica". Los Angeles Times. June 15, 1990.

- ^ "Tijuana Adopted as Sister City". Los Angeles Times. March 21, 1991.

Further reading

edit- Constance Zillgitt Snowden, Men of Inglewood, 1924.

- Roy Rosenberg, The History of Inglewood, published by Arthur Cawston, 1938.

- Lloyd Hamilton, Inglewood Community Book, 1947.