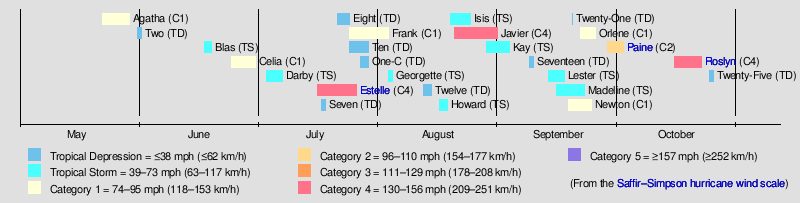

The 1986 Pacific hurricane season featured several tropical cyclones that contributed to significant flooding to the Central United States. The hurricane season officially started May 15, 1986, in the eastern Pacific, and June 1, 1986 in the central Pacific, and lasted until November 30, 1986 in both regions. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean.[1] A total of 17 named storms and 9 hurricanes developed during the season; this is slightly above the averages of 15 named storms and 8 hurricanes, respectively. In addition, 26 tropical depressions formed in the eastern Pacific during 1986, which, at the time, was the second most ever recorded; only the 1982 Pacific hurricane season saw a higher total.

| 1986 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 22, 1986 |

| Last system dissipated | October 25, 1986 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Roslyn |

| • Maximum winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 26 |

| Total storms | 17 |

| Hurricanes | 9 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 2 total |

| Total damage | $352 million (1986 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Several storms throughout the season affected land. Hurricane Estelle passed south of Hawaii, resulting in $2 million in damage and two deaths.[nb 1] Hurricanes Newton, Paine and Roslyn each struck Northwestern Mexico. While damage was minimal from these three systems near their location of landfall, Paine brought considerable flooding to the Great Plains. The overall flooding event resulted in $350 million in damage, with the worst effects being recorded in Oklahoma. Hurricane Roslyn was the strongest storm of the season, attaining peak winds of 145 mph (233 km/h).[2]

Seasonal summary

edit

Activity in the Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center's (EPHC) area of responsibility was above average. There were 25 tropical depressions, one short of the record set in 1982, which had 26.[2] Only one system formed in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's (CPHC) area of responsibility, and six others entered the CPHC area of responsibility from the EPHC area of responsibility.[3] In all, 17 systems formed, which is two storms above normal. In addition, 9 hurricanes were reported during the season, one more than average. An average number (3) of major hurricanes – Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale—was also reported.[4][5]

The season began with the formation of Hurricane Agatha on May 22 and ended with the dissipation of Tropical Depression Twenty Five on October 25, spanning 147 days. Although it was nearly two weeks shorter than the 1985 Pacific hurricane season, the season was six days longer than average. The EPHC issued 406 tropical cyclone advisories, which were issued four times a day at 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC. In 1986, hurricane hunters flew into three storms; Newton, Roslyn, and Estelle.[2][3] In Newton, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) conducted environmental research in the cyclone. In addition, the National Weather Service Field Service Station provided the East Pacific with excellent satellite coverage.[2]

During the months of May and June, four named systems developed. In July, one tropical storm and two hurricanes formed. The following month, five tropical systems developed. Towards the end of the season, tropical cyclone activity declined somewhat. While five storms formed in September, only one formed in October and none during the month of November.[4] A moderate El Niño was present throughout the season; water temperatures across the equatorial Central Pacific were 1.3 °C (34.3 °F) above normal.[6] In addition, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) was in a warm phase during this time period.[7][8]

Three tropical cyclones made landfall in 1986. The first, Hurricane Newton made landfall near Cabo San Lucas,[2] bringing minor damage.[9][10] Another storm, Hurricane Paine brushed Cabo San Lucas, and later moved inland over Sonora.[4] Paine caused minimal impacts at landfall,[11] but its remnants were described as one of the worst floods in Oklahoma history.[12] Flooding affected 52 counties in Oklahoma, which resulted in a total of $350 million in damage.[13] The final storm to make landfall during the hurricane season was Hurricane Roslyn.[2] The hurricane produced some flooding, but no serious damage.[14] In addition, Hurricane Estelle came close enough to Hawaii to require a hurricane watch.[15] Two drownings were reported, and the total damage was around $2 million.[3]

Systems

editHurricane Agatha

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 22 – May 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); |

The 1986 Pacific hurricane season's first tropical disturbance formed 865 mi (1,390 km) from the tip of Baja California Sur on May 20.[2] By 0000 UTC May 22, the circulation began to tighten and become more organized, and thus the EPHC upgraded the disturbance into Tropical Depression One-E that morning. Approximately 48 hours after becoming a tropical depression, the system was upgraded into Tropical Storm Agatha, the first storm of the season. After moving southeast, the cyclone made an abrupt change in direction, turning towards the north. Agatha strengthened into a hurricane on May 25 near the coast of Mexico, reaching its peak intensity of 75 mph (121 km/h). Turning southeast, the system quickly weakened into a tropical depression, but regained tropical storm strength on May 28, only to dissipate that day.[2] Rainfall spread around both the Atlantic and Pacific Mexican coasts, peaking at 10.75 in (273 mm) at Xicotepec de Juarez, Puebla.[16]

Tropical Depression Two

edit| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 31 – June 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance formed on May 30 in the eastern Gulf of Tehuantepec. The disturbance was moving very slowly when it was upgraded to Tropical Depression Two-E on May 31. The depression began to weaken six hours later and the final advisory by the EPHC was released on June 1.[2] Most of Mexico received rainfall, with over 3 in (76 mm) falling on Yucatán Peninsula. The worst rain occurred in Central Mexico, where over 15 in (380 mm) of precipitation fell, peaking at 18.63 in (473 mm) in Tenosique, Tabasco. The rest of the country was hit by 1–3 in (25–76 mm) of rainfall.[17]

Tropical Storm Blas

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 17 – June 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance originated from the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) on June 16. The disturbance moved west-northwest at 13 mph (21 km/h) below a weak upper-level high, becoming the third tropical depression of the 1986 season on June 17. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Blas the next day. It kept that strength for only six hours, weakening into a depression again as it moved into cooler waters. After Blas's convection dissipated, the EPHC ceased advisories on June 19[2] while situated roughly 600 mi (965 km) south of Cabo San Lucas.[4]

Hurricane Celia

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 24 – June 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); |

On June 24, five days after Tropical Storm Blas dissipated, a tropical disturbance developed south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. Later that day, its circulation had become well-defined enough for the EPHC to upgrade the disturbance into Tropical Depression Four. Winds reached 40 mph (64 km/h), enough to upgrade the system into Tropical Storm Celia on June 26. While located off the coast of Mexico, Celia strengthened into a hurricane at 1800 UTC June 27. An eye became evident on satellite imagery and the hurricane reached its peak intensity of 90 mph (140 km/h) on June 28 at 1600 UTC as it tracked near Socorro Island. Meanwhile, Celia moved into much cooler water, which resulted in rapid weakening. On June 30, Celia was downgraded into a tropical depression. The EPHC released its final advisory at 1800 UTC that day as the system had dissipated.[2]

Tropical Storm Darby

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 3 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); |

The fifth tropical cyclone of the season originated from a tropical disturbance that was first noticed on July 2. Moving northwest at about 13 mph (21 km/h), the disturbance entered warmer waters and began to develop rapidly. The disturbance was upgraded into Tropical Depression Five at 1800 UTC July 3. Turning west-northwest, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Darby on July 5. Darby peaked at 65 mph (105 km/h), and after turning northwest, encountered 77 °F (25 °C) waters. The storm began to weaken as thunderstorm activity became displaced from the center and spread northward over Arizona and California on July 6. The cyclone dissipated on July 7.[2]

Hurricane Estelle

edit| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 16 – July 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); |

During the afternoon of July 16, a tropical depression formed thousands of miles west of Mexico, and within 12 hours it strengthened into a tropical storm. On July 18, Estelle intensified into a hurricane. Located in a favorable environment, Estelle continued strengthening to become the first major hurricane of the season on July 20.[2] The hurricane entered the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility near its peak strength of 130 mph (210 km/h), a Category 4 hurricane. The hurricane veered to the west and passed south of Hawaii. Estelle weakened to a tropical storm on July 23, and on July 25, it weakened to a depression. The storm dissipated two days later.[3]

In advance of Hurricane Estelle, the National Weather Service issued a hurricane watch and high-surf advisory for the Island of Hawaii.[15] More than 200 people evacuated from their homes.[18] Huge waves crashed on the shores of the Big Island on the afternoon of July 22. The high waves washed away five beachfront homes and severely damaged dozens of others on the beach resort of Vacation Land. The total damage was around $2 million. However, only two deaths reported from the storm, both of whom drowned offshore Oahu.[3]

Hurricane Frank

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 24 – August 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); |

The EPHC began monitoring a tropical disturbance located 195 mi (315 km) southwest of San Salvador on 1800 UTC July 23. About 24 hours later, the disturbance was upgraded into a tropical depression. Initially moving towards the west-northwest due to an upper-level low and a ridge over Mexico, the storm then turned to the west as the upper-level low changed direction. By July 28, the depression was upgraded into Tropical Storm Frank. After turning back to the west-northwest, Frank reached hurricane intensity early on July 30. The storm quickly developed a well-defined eye and three hours later, Hurricane Frank reached its peak intensity as a moderate Category 1 hurricane, with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h). Hurricane Frank maintained this intensity for 18 hours. Subsequently, the hurricane began to rapidly weaken over 76 °F (24 °C) sea surface temperatures. Wind shear soon increased, thus accelerating the weakening process.[2] On July 31, Frank was reduced to tropical storm intensity.[4] Not long after weakening into a depression, the storm entered the CPHC's area of responsibility.[2] Wind shear increased further, and upon entering the region, Frank moved over slightly cooler water. It transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on August 3.[3]

Tropical Storm Georgette

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 3 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); |

On August 3, a tropical depression developed in the open ocean over 600 mi (970 km) west of the Mexican coastline. Twelve hours later, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Georgette before weakening to a depression on August 4. It then accelerated to a very rapid speed of 23 to 45 mph (37 to 72 km/h). Due to its fast speed, Georgette could not maintain a closed circulation, and thus degenerated into a non-cyclonic disturbance on August 4. The disturbance kept up its rapid forward motion, crossed the dateline and entered the western Pacific, where it reformed and reached its peak intensity as Severe Tropical Storm Georgette.[2][3] By August 16, Georgette merged with another system.[19]

Tropical Storm Howard

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 16 – August 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical wave crossed Southwestern Mexico and Belize in mid-August. A tropical disturbance developed from this wave 50 mi (80 km) south of Acapulco on August 15, the same day that the system moved offshore. Moving west-northwest south of an upper-level high, the system was classified as a tropical depression the next day about 125 mi (200 km) south of Manzanillo. Several hours later, the depression reached tropical storm intensity. Turning towards the northwest due to a trough,[2][20] it failed to intensify beyond minimal tropical storm strength.[4] Passing south of the Baja California Peninsula, the storm rapidly moved over cooler waters. Howard weakened into a tropical depression at 0600 UTC August 18. Transversing 75 °F (24 °C) water, Howard dissipated.[2] Rainfall along the southern coast reached 1 in (25 mm) in some places, with totals in excess of 5 in (130 mm) in isolated locations. Further north, rainfall was more scattered. The maximum rainfall was 9.25 in (235 mm) in Reforma, near the southern part of the country.[20]

Tropical Storm Isis

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 19 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance developed 265 mi (426 km) south of Socorro Island at 1800 UTC August 18. Twenty-four hours later the disturbance was upgraded into a tropical depression on August 19. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Isis the next day. After peaking as a moderate tropical storm at 1200 UTC August 23, Isis weakened into a depression over 74 °F (23 °C) waters early on August 24. While located some 1,500 mi (2,415 km) west of the Mexican coast, the tropical cyclone dissipated later that day.[2]

Hurricane Javier

edit| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 20 – August 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); |

On August 19, a tropical disturbance formed 460 mi (740 km) south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec and 319 mi (513 km) south of Cabo San Lucas. Satellite imagery began to show signs of developing a circulation, and the disturbance became a tropical depression on August 20 and intensified into Tropical Storm Javier hours later. Southwest of a ridge, Javier began to turn towards the west-northwest. Despite an increase in forward speed, Tropical Storm Javier underwent rapid intensification, reaching hurricane intensity at 0900 UTC August 21.[2] About three hours later, Javier reached Category 2 strength, and briefly became a major hurricane on August 22, only to rapidly weaken back to a Category 1 hurricane late on August 23.[4] Hurricane Javier sharply turned towards the north and eventually towards the northwest.[2] Early on August 24, Javier resumed intensification, regaining Category 3 intensity at 0600 UTC.[4] Passing midway between Socorro Island and Clarion Island, the storm reached its peak intensity of 130 mph (210 km/h). Moving beneath the ridge, Hurricane Javier turned to the west[2] and subsequently weakened back into a Category 3 hurricane.[4]

After briefly re-intensifying into a Category 4, the storm resumed weakening[4] due to increasing wind shear,[2] and by late on August 25, Hurricane Javier had weakened directly into a Category 2 hurricane. Shortly thereafter, Javier was downgraded into a Category 1 hurricane. While it managed to maintain marginal hurricane intensity for 24 hours.[4] on 1200 UTC August 28, the EPHC announced that Javier had weakened back into a tropical storm. Shortly after that, Javier turned towards the west-northwest due an upper-level trough. Now over 74 °F (23 °C) waters, the system continued to weaken as wind shear increased further. On August 30, Javier weakened into a depression and dissipated the next day over 1,000 mi (1,610 km) southwest of Southern California.[2] Waves were 15 feet (4.6 m) high in some areas,[21][22] prompting meteorologists to issue a high surf advisory.[23] Hurricane Javier brought the highest waves of the summer to southern California.[24]

Tropical Storm Kay

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 28 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); |

In late August, a tropical disturbance formed 725 mi (1,165 km) east-southeast of Hurricane Javier and nearly 370 mi (595 km) south of the Baja California Peninsula. Moving slowly west, the disturbance began to develop a well-defined circulation, and was respectively upgraded into a tropical depression on August 28. Passing 10 mi (16 km) south of Clarion Island, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Kay. The cyclone's forward speed increased; subsequently, Kay reached its peak intensity. After maintaining its intensity for 18 hours, Kay rapidly weakened over cold water, and was downgraded into a depression at 0000 UTC September 2. Kay dissipated the next day several hundred miles west of the Baja California Peninsula.[2]

Tropical Storm Lester

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 13 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); |

A westward-moving tropical wave increased in thunderstorm activity, soon organizing into a tropical depression on September 13. At the time of the upgrade, Lester was located more than 900 mi (1,450 km) west of the Mexican coast. Moving towards the west, the depression soon intensified into Tropical Storm Lester. After turning towards the west-northwest, Lester peaked in intensity as a moderate tropical storm.[2] Due to a combination of strong wind shear[3] and cold water, Lester began a slow weakening trend.[2] While entering the CPHC's area of responsibility at 1800 UTC September 17, Lester had already weakened to a tropical depression. Unable to maintain a closed circulation, the final advisory was issued. [3]

Tropical Storm Madeline

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 15 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance first developed during September 13 and September 14 over the warm waters south of Acapulco. On September 15, the EPHC first classified the system as a tropical depression. Rapidly moving towards the west, the depression was embedded in deep easterly flow. The system attained tropical storm intensity on 1800 UTC September 16, thus received the name Madeline. After turning towards the west-northwest, Tropical Storm Madeline accelerated. It began a slow intensification trend, and peaked as a high-end tropical storm on 0600 UTC September 18. An upper-level low introduced strong wind shear, and Madeline began to fall apart almost immediately thereafter. After turning towards the north, and slowing down, Madeline dissipated on September 22.[2]

Hurricane Newton

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 18 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 984 mbar (hPa) |

The origins of Newton were from a tropical disturbed weather near Nicaragua in mid-September. Steered by an upper-level trough located over the Western United States, the system moved westward and developed into a tropical depression at 1200 UTC on September 18. It was located beneath an anticyclone situated the Central United States and over sea surface temperatures of 84 °F (29 °C). The system steadily intensified as it paralleled the Mexican coast, and was upgraded into Tropical Storm Newton early on September 20. Within 24 hours, Newton had attained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). Meanwhile, the storm turned northwest. At 0600 UTC September 21, the EPHC reported that Newton had attained hurricane strength while located about 200 mi (320 km) west-northwest of Manzanillo, Colima. Shortly after becoming a hurricane, a NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft investigated Newton, observing winds of 79 mph (127 km/h). Six hours later, the hurricane reached its minimum pressure of 984 mb (29.1 inHg). After moving north-northwest, the hurricane briefly turned northwest, in the general direction of the Baja California Peninsula the next day. On 1800 UTC September 22, Hurricane Newton made landfall northeast of Cabo San Lucas as a minimal hurricane. After emerging into the Gulf of California, the storm reached its peak wind speed of 85 mph (135 km/h). At this time the tropical cyclone was situated about 60 mi (97 km) north of La Paz, Baja California Sur. By 1800 UTC September 23, the hurricane moved ashore near Punta Rosa and quickly dissipated. The remains of the cyclone moved into New Mexico. The remnants of Hurricane Newton transversed the Central United States and the Mid-Atlantic States until it entered the Atlantic Ocean later in the month.[4][25][2]

Prior to the system's first landfall, the EPHC noted the threat of high waves, storm surge, and flooding. In addition, the navy, army, and police were on high alert in populated areas like La Paz due to the hurricane.[26] On the mainland, roughly 700 people evacuated to shelters in Huatampo, a city that at that time had a population of 9,000, and Yavaros prior to landfall, but within hours after the passage of the hurricane, all but 127 had returned home.[27] Upon making landfall on the Baja California Peninsula, moderate rainfall was recorded though officials reported no emergencies.[26] In Huatabampo, roofs were blown off of 40 homes.[27] High winds blew down trees and utility poles.[9] In addition, a peak rainfall total of 9.23 inches (234 mm) was reported in Jopala.[25] Overall, damage in Mexico was minor and less than anticipated.[27][9][10] Because Hurricane Newton, along with a cold front, was predicted to cause heavy rains over portions of the United States, flash flood warnings and watches were issued by the National Weather Service for parts of western Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.[28][29] Across the country, the highest rainfall was 5.88 inches (149 mm) in Edwardsville, Kansas. The rainfall extended as far east as Pennsylvania.[25] In Kansas City, Missouri, 20,000 customers were without power since heavy rainfall downed power lines.[30] Snow was observed in the mountains, with up to 5 in (13 cm) of snow in Colorado. Flagstaff, Arizona recorded their earliest day of 1 in (2.5 cm) of snow on record. Winds from the storm peaked at 72 mph (116 km/h) in the state of Colorado and 64 mph (103 km/h) in the state of Kansas.[12]

Hurricane Orlene

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 21 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); |

Hurricane Orlene originated from a stationary tropical disturbance that was upgraded into a tropical depression on September 21.[2] Despite a poorly defined circulation,[3] the cyclone intensified into Tropical Storm Orlene 12 hours after formation. Steadily gaining strength, Orlene reached hurricane intensity on September 22. Shortly thereafter, the hurricane entered the CPHC's area of responsibility.[2] Upon the formation of an eye, Orlene reached its peak intensity of 80 mph (130 km/h). After maintaining peak intensity for 24 hours, Hurricane Orlene began to encounter strong wind shear. Subsequently, Orlene weakened rapidly and lost hurricane status at 1800 UTC September 23. The system weakened into a tropical depression on September 24. Tropical Depression Orlene dissipated the next day.[3]

Hurricane Paine

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 28 – October 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance developed on September 27 within 250 mi (400 km) of the Mexican coastline.[2] The disturbance was upgraded into Tropical Depression Twenty-Three on 0000 UTC September 28. Tropical Depression Twenty-Three moved west-northwestward, lured poleward by an upper-level trough near northern Mexico. At 0000 UTC September 30, the depression became Tropical Storm Paine, southwest of Acapulco. Roughly 21 hours later, a NOAA Hurricane Hunter flight found winds of 90 mph (140 km/h), upgrading Paine into hurricane. The hurricane peaked as a Category 2 hurricane on October 1 as it turned northwest, headed towards the Gulf of California. Hurricane Paine did not intensify further due to the presence of mid-level wind shear and dry air.[2] The outer eyewall moved across Cabo San Lucas, and the resultant land interaction was believed to have slightly weakened the inner core of the hurricane.[31] Paine moved ashore near San José, Sonora with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The storm weakened as it moved over land going through Mexico and then entering the United States. Paine dissipated on October 4 over Lake Michigan.[2][32]

Rainfall from the tropical cyclone was significant in Mexico and the United States. Light rain fell in Cabo San Lucas. Meanwhile, rains around the Mexican Mainland peaked at 12 inches (300 mm) in Acapulco.[32] Near the area around where it made landfall, strong winds knocked down trees and caused disruptions to city services.[11] In the United States, rainfall peaked at 11.35 inches (288 mm) in Fort Scott, Kansas.[32] The Barnsdall, Oklahoma weather station recorded 10.42 inches (26.5 cm) on September 29, which set a record for the highest daily precipitation for any station statewide. The flooding affected 52 counties in Oklahoma, which resulted in a total of $350 million in damage.[13] In all, Paine was described as one of the worst floods in Oklahoma history.[33] Flooding from Paine resulted in about 1,200 people homeless in East Saint Louis, Illinois[34] and resulted in record discharge rates along many streams and creeks. Subsequently, many reservoirs were nearly filled to its capacity. For example, the Mississippi River in St. Louis reached the fifth highest flood stage on record.[35]

Hurricane Roslyn

edit| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 15 – October 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance moved westward offshore Nicaragua and was declared Tropical Depression Twenty-Four on October 15.. During the early afternoon of the next day, ship reports indicated the formation of a tropical depression close to land. The cyclone moved at a quick pace towards the west-northwest south of a warm-core ridge. Early on the morning on October 16, Roslyn became a tropical storm. By the morning of the October 17, Roslyn had developed into a hurricane south of Acapulco.[2] A vigorous upper trough was deepening offshore Baja California, and Roslyn began to re-curve within a few hundred miles of Manzanillo.[36] The system struck Mazatlán as a marginal hurricane on October 20.[2] The low-level center rapidly dissipated, although a frontal low developed in the western Gulf of Mexico, which moved over southeastern Texas and later through the Mississippi Valley. The original upper-level circulation maintained its northeast movement, bringing rainfall to the Southeastern United States.[36]

Affecting a sparsely populated area, the highest reported winds from a land station were 44 mph (71 km/h). Roslyn produced some flooding, but no serious damage.[14] Impact was limited to flooded homes and factories, as well as some crop damage and beach erosion[2][37] and only one yacht sunk.[2] The remnants of Hurricane Roslyn produced heavy rainfall across the central and southern United States. In Matagorda, Texas, a total of 13.8 in (35 cm) was reported.[36]

Other systems

editIn addition to the 17 named storms, there were eight tropical depressions during the season that failed to reach tropical storm strength. The second, Tropical Depression Seven, began as a large area of thunderstorms near Hurricane Estelle on July 17. Moving at a steady pace, the cyclone failed to intensify and attained peak intensity of 30 mph (45 km/h). Cool sea surface temperatures and its proximity to Hurricane Estelle eventually caused the depression to dissipate late on July 18.[2]

Tropical Depression Eight formed on July 21 while located 1,000 mi (1,610 km) southwest of the Baja California Peninsula. Initially moving west-northwest around an upper-level high, the depression peaked with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h). It dissipated on July 24.[2][38] Another tropical disturbance formed on July 24. A circulation developed two days later, and thus it was classified as Tropical Depression Ten. The cyclone remained a tropical depression for about three days before moving into the CPHC's area of responsibility on 1000 UTC July 27. A slow weakening trend began as the depression continued to move west at speeds of 30 mph (50 km/h). By 1800 UTC on July 29, it had become poorly organized around 1,000 mi (1,610 km) west-southwest of the Hawaiian Islands, and the final advisory was issued.[2][3][38]

Tropical Depression One-C formed on July 27, possibly from the remnants of Tropical Depression Eight that dissipated a few days earlier well to the east of 140 °W. The depression tracked westward at a fairly rapid forward speed of 35 mph (55 km/h); however, it failed to develop past the depression stage. One-C passed well south of the Hawaiian Islands on July 28. On July 29 at 0000 UTC, it had dissipated to the southwest of the Hawaiian Islands and the final advisory was issued by the CPHC.[3][38]

An area of disturbed weather developed a circulation on August 12 and was upgraded into Tropical Depression Twelve nearly 700 mi (1,100 km) south of the Baja California Peninsula. It drifted slowly to the northwest until it dissipated near 22 °N 110 °W on August 14. Peak maximum sustained winds were estimated at 35 mph (55 km/h).[2] Tropical Depression Seventeen formed on September 8, 30 km (20 mi) east of Socorro Island and dissipated on September 9 over cold water without becoming a tropical storm.[2]

One of the last cyclones of the season formed from a westward-moving tropical disturbance in the ITCZ.[2] The disturbance moved at about 10 mph (20 km/h) and upon developing a circulation, was declared Tropical Depression Twenty-One at 0600 UTC September 19. However, the depression lasted for only six hours before dissipating, likely due to the close distance between it and Tropical Storm Madeline.[2] Tropical Depression Twenty-Five was the final tropical depression of the 1986 season.[2] It formed on October 22 at 1800 UTC near the 140°W line. Due to strong wind shear, the stationary storm had dissipated within 30 hours of formation.[2] Even though no more official systems developed, a forecaster at the National Hurricane Center remarked that an unnamed tropical storm may have formed in November.[39]

Storm names

editThe following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Pacific Ocean east of 140°W in 1986.[40] This is the same list used for the 1980 season.[41] A storm was named Paine for the first time in 1986, while Orlene and Roslyn were previously used in the old four-year lists.[42] No names were retired from this list following the season, and it was used again for the 1992 season.[43]

|

|

For storms that form in the North Pacific from 140°W to the International Date Line, the names come from a series of four rotating lists. Names are used one after the other without regard to year, and when the bottom of one list is reached, the next named storm receives the name at the top of the next list.[44] No named storms formed in the central North Pacific in 1986. Named storms in the table above that crossed into the area during the year are noted (*).[3]

See also

edit- List of Pacific hurricanes

- Pacific hurricane

- 1986 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1986 Pacific typhoon season

- 1986 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1985–86, 1986–87

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 1985–86, 1986–87

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1985–86, 1986–87

Notes

edit- ^ All damage totals in United States dollars are in their values in 1986 unless otherwise noted.

References

edit- ^ Neal Dorst. "When is hurricane season?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au Emil B. Gunther; R.L. Cross (October 1987). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1986". Monthly Weather Review. 115 (10): 2507–2523. Bibcode:1987MWRv..115.2507G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1987)115<2507:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n The 1986 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (PDF) (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. 2007. Archived from the original on June 22, 1987. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Blake, Eric S; Gibney, Ethan J; Brown, Daniel P; Mainelli, Michelle; Franklin, James L; Kimberlain, Todd B; Hammer, Gregory R (2009). Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Basin, 1949-2006 (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2024. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Historical El Nino/La Nina episodes (1950–present)". Climate Prediction Center. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ "Variability of rainfall from tropical cyclones in Northwestern Mexico" (PDF). Atmosfera. 2008. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ Franco Biondi; Alexander Gershunov; Daniel R. Cayan (2001). "North Pacific Decadal Climate Variability since 1661". Journal of Climate. 14 (1): 5–10. Bibcode:2001JCli...14....5B. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<0005:NPDCVS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Hurricane Newton rips across Mexico". Daily Herald. September 24, 1986.

- ^ a b "Pacific Hurricane hits northwest Pacific coast". Ocala Star-Banner. September 25, 1986.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Paine Sweeps Into Mexico". Akron Beach Journal. October 10, 1986.

- ^ a b Thunderstorms and the remnants of hurricane Newton brought rain..., UPI, September 24, 1986

- ^ a b Johnson, Howard (2003). "Oklahoma Weather History, Part 9 (September)". Oklahoma Climatological Survey. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ a b "Tropical Storm Roslyn Hits Mexican Coast". The Ledger Wire Services. October 23, 1986. p. 4. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Estelle aims for Hawaii". The Milwaukee-Journal. July 22, 1986. p. 31. Retrieved September 11, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Roth, David (July 19, 2007). Hurricane Agatha – May 22–29, 1986 (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ David Roth (July 16, 2007). "Tropical Depression #2E – May 27 – June 2, 1986". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ "Estelle forces evacuations". The Telegraph-Herald. July 22, 1986. p. 43. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ^ Fatjo, Steve J. "Typhoons Georgette (11E) and Tip (10W)" (PDF). 1986 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center. pp. 58–66. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2009). "Tropical Storm Howard". Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ "Surf's Up Just In Time For International Event". The Modest. August 30, 1986. p. 10. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ "Surf's Still Up". The Modest. August 31, 1986. p. 11. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ "Hurricane Javier deteriorating 1,000 miles away". L.A. Times. August 30, 1986.

- ^ "Big Waves for Chairman on Boards". L.A. Times. August 28, 1986.

- ^ a b c David Roth (2007). "Hurricane Newton - September 17–26, 1986". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved August 10, 2007.

- ^ a b "Hurricane moves northwest". The Lewiston Journal. September 23, 1986. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Hurricane lashes Mexico coast". The Day. September 23, 1986. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ "Around the Nation". The Capital. September 24, 1986.

- ^ "Storms Raged Across Nation". The Telegraph-Herald. September 24, 1986. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ "Winter rears its ugly..." Lodi News-Sentinel. September 25, 1986. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ Sean K. Daida; Gary M. Barnes (2002). "Hurricane Paine (1986) Grazes the High Terrain of the Baja California Peninsula". Weather and Forecasting. 18 (5). American Meteorological Society: 981–990. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2003)018<0981:HPGTHT>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

- ^ a b c Roth, David (2007). "Hurricane Paine – September 26 – October 4, 1986". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ^ "Floods Hit Tulsa Area". United Press International. October 6, 1986. p. 1. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Flooding victims left homeless". Associated Press. September 29, 1986. p. 12. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ C.A. Perry; B.N. Aldridge; H.C. Ross (2000). "Summary of Significant Floods in the United States, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, 1986". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ a b c David Roth (2007). "Hurricane Roslyn – October 18–26, 1986". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ^ Yovani Montaño Law; Mario Gutiérrez-Estrada (1988). "Dynamics of Beaches Raft River Delta, Mexico". National Autonomous University of Mexico. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Roth, David (February 4, 2011). "Extended Best Track Database for CLIQR program". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ Todd Kimberlain (April 16, 2012). Re-analysis of the Eastern North Pacific HURDAT. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ "Andrew, Agatha, top 1986 list". The Gadsden Times. Gadsden, Alabama. May 23, 1986. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1980. p. 11. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Name History". Atlantic Tropical Weather Center. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. April 1992. pp. 3-5, 7–9. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2022.