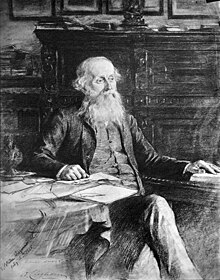

Hugh Francis Clarke Cleghorn (9 August 1820 – 16 May 1895) was a Madras-born Scottish physician, botanist, forester and land owner. Sometimes known as the father of scientific forestry in India, he was the first Conservator of Forests for the Madras Presidency, and twice acted as Inspector General of Forests for India. After a career spent in India Cleghorn returned to Scotland in 1868, where he was involved in the first ever International Forestry Exhibition, advised the India Office on the training of forest officers, and contributed to the establishment of lectureships in botany at the University of St Andrews and in forestry at the University of Edinburgh. The plant genus Cleghornia was named after him by Robert Wight.

Early life

editCleghorn was born in Madras on 9 August 1820, where his father, Peter (also known as Patrick) (1783 – 1863) was Registrar and Prothonotary in the Madras Supreme Court. His mother Isabella (née Allan) died in Madras (1 June 1824) when Cleghorn was three and a half years old.[2] In 1824 Cleghorn and his younger brother were sent home to Stravithie, near St Andrews, Fife, to the care of his grandfather, Hugh Cleghorn (1752–1837), who had been Professor of Civil History at St Andrews University and was later the first British colonial secretary of Ceylon.[3] Cleghorn received his early education at the Royal High School, Edinburgh. Following an illness Cleghorn then attended the newly founded Madras College in St Andrews and in 1834 he entered the arts faculty of the United College of St Salvator and St Leonard of St Andrews University.[4] While at Stravithie, under the influence of his grandfather, an improving laird, the young Hugh acquired an interest in estate management (including forestry) and botany. In 1837 he went to study medicine at Edinburgh, during which period he was apprenticed to the surgeon James Syme and studied botany under Robert Graham. He graduated MD from the University of Edinburgh in 1841 and the following year was appointed to the East India Company as an Assistant Surgeon in the Madras Presidency.[5][6]

India

editCleghorn's first post was in the Madras General Hospital and, after various military postings, was appointed to the Mysore Commission in 1845. For the next two years he was based at Shimoga and pursued his interest in botany, encouraged by Sir William Jackson Hooker[7] who had suggested that he "study one plant a day for a quarter of an hour".[8][9] It was here that Cleghorn began to commission botanical drawings,[10] took a special interest in economic botany and noticed a decline in teak forests that had occurred since a visit by Francis Buchanan(-Hamilton) in 1801.

In 1848, suffering from 'Mysore fever', he returned on sick leave to Britain. He took an active part in scientific organisations, such as the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, to which he read several papers including one on hedge plants.[11] He read the same paper at the annual meeting of the British Association held in Edinburgh in 1850, which won him a 'medium gold medal' of the Highland and Agricultural Society in 1851.[12] At the same meeting, under the chairmanship of Sir David Brewster, Cleghorn was commissioned to write a report on the effects of tropical deforestation. A summary of this was read at the Association's Ipswich meeting on 7 July 1851, and subsequently published in full. He was requested by John Forbes Royle to assist in cataloguing the Indian botanical exhibits for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Cleghorn returned to India in 1852 and was appointed acting Professor of Botany and Materia Medica at Madras Medical College by Sir Henry Pottinger, a post confirmed two years later. During this period he became an active member of the Madras Literary Society and the Madras Agri-Horticultural Society.[5][13] One of his students, Pulney Andy, became the first Indian to receive a medical degree from Scotland. John Shortt was another of his local students. In 1853 he published Hortus Madraspatensis, a catalogue of the plants in the latter Society's Garden. Cleghorn was consulted by the Madras Government on various economic-botanical subjects, resulting in papers such as one on the sand-binding plants of the Madras beach,[14] read to the Madras Literary Society in 1856. Cleghorn also played a major role in the Madras Exhibitions of 1855 and 1857.[15]

Madras Forest Department

editIn 1855, on the advice of the civil servant Walter Elliot, Cleghorn was asked by the Governor of Madras, Lord Harris, to organise a Forest Department for Madras and to start systematic forest conservancy, such has had earlier been established in Bombay under Alexander Gibson. He was appointed Conservator of Forests on 19 December 1856, which he held until 10 October 1867, most actively so until 1860.[5]

Pressures on the forests of the Presidency, which included those of the southern part of the Western Ghats, and as far north as Orissa on the east coast, were great. This was the time of the early development of railways in India and Cleghorn estimated that a mile of rail line needed 1760 wooden sleepers, which had a lifespan of only eight years. In addition to sleepers, wood was also required to run the steam engines of the railways and for steamships. By his estimate, there was no way to maintain the supply without destroying the forests unless active management was undertaken. He pointed out that in Britain requirement for wood was less, due to the country's substantial reserves of coal and the ability to import wood from other parts of its Empire.[5]

By this date it was already well known that forests had a major influence on climate, as were the negative effects of deforestation on rainfall and river flow. In his 1851 British Association report Cleghorn had summarised existing literature[5] and cited anecdotal information from other East India Company surgeons including Alexander Gibson and Edward Balfour. The importance placed by Gibson and Cleghorn on climate-modification (rather than purely economic concerns) as the motivation for their system of forest 'conservancy' is one that has been much discussed by historians of forestry and ecology. Claims by authors, notably Richard Grove in his Green Imperialism, that it was the major motivation of the East India Company surgeon-Conservators have recently been disputed. In 1860 Cleghorn's persistent campaigning with the Government resulted in the banning in the Madras Presidency of 'kumri', a form of shifting cultivation he considered particularly damaging.

One of his first acts as Conservator was a brief trip to Burma in January 1857, when he met Dietrich Brandis, who was already working there on the teak forests. Having witnessed their denudation by private business interests, Cleghorn believed that the State had to take the main role in preserving forests.[5] As Conservator Cleghorn spent a great part of the year in travels surveying forest resources in the vast territory for which he was responsible, with three major tours each of more than six months in 1857, 1858 and 1860. Shorter tours were made to the sal forests of Orissa in the spring of 1859, and a productive week in the Anamalai Hills in September 1859. On the latter he was accompanied by Richard Henry Beddome (who succeeded Cleghorn as Conservator in Madras) and Major Douglas Hamilton, a talented artist who recorded the expedition visually.[16]

On his third forest tour Cleghorn again contracted fever and obtained a year's sick leave to Britain in September 1861. During this leave he interacted with the India Office, which allowed the publication of a compilation of his forest reports as The forests and gardens of South India. Though his goal may have been to supply a manual to enable forest assistants to work more effectively for the benefit of the State, the book is mainly a compilation of his reports documenting his activities in forest conservancy in the Madras Presidency during the four years that the department had by then been in operation.[17][18]

In Scotland, as on his previous leave, Cleghorn read papers to the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, and his Anamalai one to the Royal Society of Edinburgh (to which he was elected on 1 December 1862). The most notable event of this leave, however, was Cleghorn's marriage at Penicuik, on 8 August, to Marjorie Isabella, known as 'Mabel', daughter of Charles Cowan a notable philanthropist and paper-maker.[6][19]

Forest Department of India

editOn returning to India with Mabel in October 1861 Cleghorn was summoned to Calcutta by Lord Canning and charged with surveying the forests of the Punjab Himalaya. He continued this under Sir Robert Montgomery, Lt Governor of the Punjab, which led to Cleghorn's being based in Lahore, where he was involved in the 1864 Punjab Exhibition. The same year he was involved in a Missionary Conference in Lahore, evangelical Christianity, especially with a medical bias, underpinning the whole of Cleghorn's life and work. His second book The Forests of the Punjab (1864) is a compilation of his reports from this period. In December 1862 Lord Elgin had summoned Brandis from Burma to reorganize the Forest Department and in January 1864 Brandis and Cleghorn were appointed joint Commissioners of Forests; three months later Brandis was given the senior post of Inspector General. The pair worked together on the Indian Forest Act, which came into effect on 1 May 1865, following which Cleghorn was given a six-month leave to take his ailing wife home, and to attend to Stravithie following the death of his father. During two periods when Brandis was on leave in Europe Cleghorn acted as Inspector General (July 1864 to January 1865, and May 1866 to March 1867). Following the second of these Cleghorn returned to Madras, where he was given 20 months' leave in October 1867, though he was never return to India, and formally retired at the expiry of this period.[5]

Retirement

editIn November 1867 Cleghorn met up with Mabel in Malta, which resulted in a report on the agriculture and botany of Malta and Sicily the following year.[21][22] Back in Britain he acted as an adviser to the Secretary of State for India and assisted with the selection of candidates for the Indian Forest Service.[5] A member of the Edinburgh Botanical Society since 1838, he was elected its president in 1868–69 (succeeded by Walter Elliot).[23] In 1872 he was elected president of the Scottish Arboricultural Society for two years, and subsequently played an instrumental role in the establishment of a lectureship in Forestry at the University of Edinburgh. Cleghorn also gave his opinions to the Select Committee of the House of Commons in 1885 on the topic of forestry education in Britain.[24][25] Cleghorn wrote the entries on 'Arboriculture' (1875) and 'Forests' (1879) for the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Cleghorn died at Stravithie, in the mansion that he had largely rebuilt, on 16 May 1895. The heir to the property was his nephew Alexander Sprot (later Sir Alexander, 1st Baronet), son of Cleghorn's sister Rachel Jane, widow of Alexander Sprot of Garnkirk.[6]

In 1848 his friend Robert Wight dedicated the genus Cleghornia to him as a 'zealous cultivator of Botany, but more especially directing his attention to Medical Botany'.[26]

The Cleghorn Collection

editSome 3000 botanical drawings were commissioned and assembled by Cleghorn, mainly drawn in India. These now largely reside with the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, having been assembled from major donations from Edinburgh University, the National Museum of Scotland and the private collection of Dr Cleghorm of Stravithie, but with Edinburgh University still retaining a proportion of the works for their own use.[27]

Botanical authorship

editAlthough Cleghorn published no descriptions of new plant species, a single invalid plant name has been attributed to him.

Notes

edit- ^ Noltie (2016a):236.

- ^ Addison, W. Innes (1901). The Snell Exhibitions. Glasgow: James MacLehose & Sons. p. 79.

- ^ Rogers, Charles (1889). The Book of Robert Burns. Volume 1. Edinburgh: Grampian Club. p. 124.

- ^ Noltie (2016a):7-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Das, Pallavi (2005). "Hugh Cleghorn and Forest Conservancy in India". Environment and History. 11 (1): 55–82. doi:10.3197/0967340053306149. S2CID 210989732.

- ^ a b c "Death of Dr H.F.C. Cleghorn". Evening Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 17 May 1895. p. 2. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Noltie (2016a):22. [Note that Cleghorn mistakenly credited Hooker jr.]

- ^ "Principal Sir William Muir and the Botanic Gardens". Edinburgh Evening News. 8 August 1888. Retrieved 28 October 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Cleghorn, H. (1869). "Presidential address". Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 10: 261–277. doi:10.1080/03746607009468692.

- ^ Noltie, Henry (2016). The Cleghorn Collection: South Indian Botanical Drawings 1845-1860. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. ISBN 9781910877111.

- ^ Cleghorn, Hugh F. C. (1850). "On the Hedge Plants of India, and the conditions which adapt them for special purposes and particular localities". Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 4 (1–4): 1–4, 83–100. doi:10.1080/03746605309467595.

- ^ "Highland & Agricultural Society". Inverness Courier. 17 July 1851. p. 4 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Presentation to Hugh Cleghorn of Stravithie". Transactions of the Royal Scottish Arboricultural Society. 12: 198–205. 1890.

- ^ Cleghorn, Hugh (1856). "Notulae Botanicae No.1. On the sand-binding plants of the Madras Beach". Journal of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India. 9: 174–177.

- ^ Brandis, Dietrich (1888). "Dr Cleghorn's services to Indian Botany". Indian Forester. 4: 14.

- ^ Cleghorn, M.D. (1861). "Expedition to the Higher Ranges of the Anamalai Hills, Coimbatore, in 1858". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 22 (3): 579–587. doi:10.1017/s0080456800031422. S2CID 130606989.

- ^ Cleghorn, Hugh Francis Clarke (1861). The Forests and Gardens of South India. London: W. H. Allen.

- ^ Brandis, D. (1888). "Dr Cleghorn's Services to Indian Forestry". Transactions of the Royal Scottish Arboricultural Society. 12: 87–93.

- ^ "Marriages". Dundee Courier. British Newspaper Archive. 10 August 1861. p. 1.

- ^ Noltie, H. J. (7 August 2011). "A botanical group in Lahore, 1864". Archives of Natural History. 38 (2): 267–277. doi:10.3366/anh.2011.0033. PMID 22165442. Retrieved 7 August 2022 – via PubMed.

- ^ Cleghorn, H. (1869). "Notes on the Botany and Agriculture of Malta and Sicily". Transactions of the Scottish Arboricultural Society. 11 (1): 106–139.

- ^ Cleghorn, Hugh (1870). "Opening Address by the President". Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 10 (1–4): 261–284. doi:10.1080/03746607009468692. ISSN 0374-6607.

- ^ The Botanical Society of Edinburgh 1836–1936. Edinburgh: Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 1936. p. 15.

- ^ "Obituary: Hugh F. C. Cleghorn, M. D., LL. D., F. R. S. E.". The Geographical Journal. 6 (1): 83. 1895. JSTOR 1773955.

- ^ "Report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons, 1885, on Forestry". Transactions of the Scottish Arboricultural Society. 11 (2): 119–154. 1885.

- ^ Wight, Robert (1848). Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis or Figures of Indian Plants. Volume IV part 2. Madras: P.R. Hunt, American Mission Press. p. 5.

- ^ The Cleghorn Collection by H J Noltie ISBN 978-1-910877-11-1

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Cleghorn.

Cited references

edit- Noltie, H. J. (2016a). Indian Forester, Scottish Laird. The Botanical Lives of Hugh Cleghorn of Stravithie. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. ISBN 9781910877104.

- Noltie, H. J. (2016b). The Cleghorn Collection: South Indian Botanical Drawings 1845-1860. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. ISBN 9781910877111.

External links

edit- Works by or about Hugh Cleghorn at the Internet Archive

- Cleghorn, H. (1864) Report upon the Forests of the Punjab and the western Himalaya. Thomason Civil Engineering College, Roorkee.

- Cleghorn, H. (1858) Memorandum upon the pauchontee or Indian gutta tree of the western coast. Government of Madras