Huamelulpan is an archaeological site of the Mixtec culture, located in the town of San Martín Huamelulpan at an elevation of 2,218 metres (7,277 ft), about 96 kilometres (60 mi) north-west of the city of Oaxaca, the capital of Oaxaca state.

| Mixtec Culture – Archaeological Site | ||

|---|---|---|

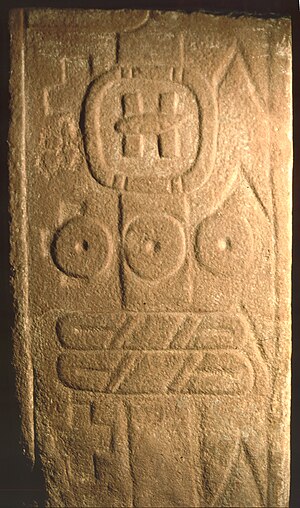

Stela at Huamelulpan Stela at Huamelulpan

| ||

| Name: | Archaeological Site Huamelulpan | |

| Type | Mesoamerican archaeology | |

| Location | San Martín Huamelulpan, Oaxaca | |

| Region | Mesoamerica | |

| Coordinates | 17°33′02″N 97°24′58″W / 17.55056°N 97.41611°W | |

| Culture | Mixtec (Lower) | |

| Language | Mixtec | |

| Chronology | 400 BCE to 800 CE | |

| Period | Mesoamerican Preclassical, Classical and Postclassical (Ramos Phase[1]) | |

| Apogee | 300 BCE – 200 CE | |

| INAH Web Page | ||

Because of its dimensions it must have been one of the largest Mesoamerican cities of its time, and also one with the longest occupation, from the Preclassic to the Postclassic Periods. The apogee of the settlement is estimated at the Ramos Phase (300 BCE – 200 CE), the period of Mesoamerican urban society's development.

The site was part of other early settlements in the region, such as Cerro de las Minas, Yucuita, Diquiyú and Monte Negro. Their apogee is characterized by monumental architecture and sculptures, there is also evidence of clear social stratification within their residential zones.[2]

During site investigations many high quality urns were found here, similar Zapotec samples were found in the central valleys. Carved monoliths were found at the site, these are considered to be unique since none have been found at other Mixtec urban centers that have such similarity to the Zapotec writing of Monte Albán.[2]

History

editThe foundation of this ancient prehispanic city goes back to 400 BCE, it was an important urban center up to 800 CE; it is a good sample of the early Mixtec culture, called Ñuu Sa Na' or "Ancient People" (Ñuu Yata in the Mixteca Baja).[2]

During their early urban stages, Huamelulpan and the main Mixtec centers maintained complex and variable relations with Monte Albán. Towards 200 CE, some Mixtec centers were partially or totally abandoned and between 400 and 800 CE, there was another urban center boom, when Huamelulpan and other sites lost their close relationships with Monte Albán and established new relations with Lower Mixtec centers linked with groups from Puebla and perhaps the Valley of Mexico. The Lower Mixtec (Ñuiñe) culture developed at this time. The city was abandoned by the Postclassic and it was only used for sumptuary burials.[2]

According to archaeological history, the site was a very important Mixtec center, where tributes were received, to be traded with Puebla, Tehuacán and all of Oaxaca to the Pacific coast; from Tehuacán and Puebla traded fabrics and yarns, from the coast traded chilies, Jamaica, jicaras,[3][4] dried fish, salt, sea shells used for necklaces, earrings, etc.[5]

Ancient Huamelulpan had important weapon and fur workshops.[5]

Discovery

editThe Huamelulpan archaeological site was discovered in 1933 by Alfonso Caso and many of the pieces found are in exhibition at the Town Community Museum.

Toponymy

editThe name Huamelulpan comes from the Nahuatl language, a language that was not spoken by the original inhabitants. Its Nahuatl name means "In the huautli mound", the Mixtec name is Yucunindaba, and it means "Hill that flew".[6]

Jansen y Pérez Jimenez offer an alternative opinion, that the native name is Yucunundaua, which translates "Hill of the Wooden Columns".

According to the Mexico Municipalities Encyclopedia, the name Huamelulpam was developed from two huamil trees that grew together and formed a letter (h), the story goes that these trees lasted for centuries, and the town was called Huamelulpam.[5]

Mixtec phases

editThe Alta-Mixteca region development has been segregated into various phases; Cruz, Ramos, Las Flores and Natividad, that covers the region development from about 1500 BCE to 1530 CE.[1]

Cruz-Ramos transition. During the transition from the mid-formative period (Late Cruz) to the late- formative (Early Ramos) the number of sites decreased in the studied area.[1]

It is considered a consequence of the development of early Mixtec urban centers – a process observed elsewhere in Oaxaca – the Central Valleys, the Huamelulpan Valley, and the Eastern Nochixtlán Valley. Two of the Early Ramos sites – Monte Negro and Cerro Jazmin – were already urban centers covering more than one km2.[1]

There is an apparent absence of settlements dating to the Late Ramos (200 B.C.-200 A.D.) in the major part of the area surveyed (only 15 sites, 170 ha comparing to 62 sites and 700 ha of Early Ramos). It is a striking fact because in Yucuita and Huamelulpan this period was a time of the major centralization and florescence of the regional states and general growth of the population. At the same time only two sites in the surveyed area had continuous occupation from Early Ramos to Early Flores while 20 had a gap between these phases.[1]

| Phase | Chronnology | Tlaxiaco | Teposcolula | Nochixtlán | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cruz | 1500–300 BCE | 47 Sites | 40 Sites | 29 Sites | 116 Sites | |

| Ramos | 300 BCE – 200 CE | 41 Sites | 27 Sites | 10 Sites | 78 Sites | |

| Las Flores | 200–1000 CE | 92 Sites | 67 Sites | 49 Sites | 208 Sites | |

| Natividad | 1000–1530 CE | 199 Sites | 179 Sites | 88 Sites | 466 Sites | |

| Regional survey in the Central Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca, México. Conducted between January 1 and June 15, 1999.[1][7] | ||||||

Mixtec culture

editThe Mixtec (or Mixteca) are indigenous Mesoamerican peoples inhabiting the Mexican states of Oaxaca, Guerrero and Puebla in a region known as La Mixteca. The Mixtecan languages form an important branch of the Otomanguean language family.

The name "Mixtec" is a Nahuatl exonym, from [miʃ] 'cloud' [teka] 'inhabitant of place of'.[8] Speakers of Mixtec use an expression (which varies by dialect) to refer to their own language, and generally this expression means "word of the rain": Tu'un Sávi [tũˀũ saβi] in one variety, for example, and Dà'àn Dávi [ðãˀã ðaβi] in another.

Mixtec language

editThe Mixtecan languages constitute a branch of the Otomanguean language family of Mexico. The Mixtecan branch includes the Trique (or Triqui) languages, spoken by about 24,500 people; Cuicatec, spoken by about 15,000 people; and the large group of Mixtec languages proper, spoken by about 511,000 people.[9] Again, the Mixtec languages proper are a grouping within the Mixtecan branch of the Otomanguean family. Virtually all of the remainder of this article is about Mixtec proper; for Cuicatec and Trique, see the separate articles. The internal classification of the Mixtecan branch, i.e., the subgrouping between Trique, Cuicatec, and Mixtec proper, is an open question.[10] As to the Mixtec languages proper, identifying how many there are poses challenges at the level of linguistic theory. Depending on the criteria for distinguishing between a difference of dialects and a difference of languages, there may be as many as 50 different Mixtec languages[11]

Language, codices, and artwork

editThe Mixtecan languages (in their many variants) were estimated to be spoken by about 300,000 people at the end of the 20th century, although the majority of Mixtec speakers also had at least a working knowledge of the Spanish language. Some Mixtecan languages are called by names other than Mixtec, particularly Cuicatec (Cuicateco), and Triqui (or Trique).

The Mixtec are well known in the anthropological world for their Codices, or phonetic pictures in which they wrote their history and genealogies in deerskin in the "fold-book" form. The best known story of the Mixtec Codices is that of Lord Eight Deer, named after the day in which he was born, whose personal name is Jaguar Claw, and whose epic history is related in several codices, including the Codex Bodley and Codex Zouche-Nuttall. He successfully conquered and united most of the Mixteca region.

They were also known for their exceptional mastery of jewelry, in which gold and turquoise figure prominently. The production of Mixtec goldsmiths formed an important part of the tribute the Mixtecs had to pay to the Aztecs during parts of their history.

Mixtec writing

editMixtec writing originated as a pictographic system during the Post-Classic period in Mesoamerican history. Records of genealogy, historic events, and myths are found in the pre-Columbian Mixtec codices. The arrival of Europeans in 1520 CE caused changes in form, style, and the function of the Mixtec writings. Today these codices and other Mixtec writings are used as a source of ethnographic, linguistic, and historical information for scholars, and help to preserve the identity of the Mixtec people as migration and globalization introduce new cultural influences.

The site

editThe archaeological site includes two sets of terraces, arranged in the slope of a hill. The first set has platforms with slopped walls, stairway, hydraulic system and stands with carved numerals. The second group is integrated by two platforms, formed by rectangular structures with slopped walls and stucco remains. In addition to these groups, there are several tombs and mounds not yet explored.[12]

Structures

editThe main structures of this group are oriented to the west and include: a large square platform, with a central plaza and knolls in three sides; a large terrace or Plaza 2 with an altar; and a ballgame court I shaped, 70 meters long. The explorations in the residential zones produced findings of tombs and burials with ceramics and other offerings.

There are five main sets at the site, each with several structures.

Cerro Volado

editThis group is formed by two large plazas with a mound in the center; others of smaller size are dispersed in the plazas.

Pantheon Group

editThe group is located to the foot of the "Cerro Volado" and has four low platforms around a patio.

Old Church

editThe group is made up by two badly damaged platforms, with a housing area located between this group and the Pantheon.

The Church Group is the largest; it is a hill terrace east of the center of the municipality, with old constructions in its slopes and on which a modern-day church was built with stones removed from the ancient constructions, these can be seen embedded in its walls with visible carved characters.

Western Group

editThe group west of the Church has several platforms constructed at different levels.

Regional communication

editRegional communications in ancient Mesoamerica are believed to have been extensive. There were various trade routes attested since prehistoric times.

Scholars have long identified a number of similarities between the ancient Guatemalan and Mexican art styles and cultures. These similarities start as far north as the Mexico Central Plateau and continue to the Pacific coast and as far as Central America. There are many common elements in iconography, stone sculptures and artefacts. All this led to the investigation of possible trade patterns and communication networks.

It is certain this route played a critical role in the political and economic development of southern Mesoamerica, although its importance varied over time. There was material and information trade between the Mexico Central Plateau, the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

See also

edit- Mixtec Culture

- Yucuita

- San José Mogote

- Cerro de las Minas

- Izapa

- Guerrero

- Oaxaca

- Chiapas

- Chalcatzingo

- Oxtotitlán

- Juxtlahuaca

- Teopantecuanitlan

- Costa Chica

- Mazatán, Chiapas

- Comitán

- Chiapa de Corzo

- Tapanatepec

- Tonalá

- Pijijiapan

- Chiautla

- Huamuxtitlán

- Tlapa

- Ometepec

In Guatemala:

- Tak´alik Ab´aj,

- Bilbao

- Huehuetenango

- Quetzaltenango

- Chimaltenango

- Mixco Viejo

- Retalhuleu

- Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa

- Escuintla

In El Salvador:

In Nicaragua:

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e f Beliaev, Dmitri (1999). "Regional Survey in the Central Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca, México". FAMSI. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Maldonado A., Benjamín. "Huamelulpan archaeological site". INAH (in Spanish). Mexico. Archived from the original on 2010-09-27. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ Crescentia cujete, commonly known as the Calabash Tree, is a species of flowering plant that is native to Central and South America. It is a dicotyledonous plant with tripinnate leaves. It is naturalized in India

- ^ Jícara is a náhuatl word; xicalli, drinking vessel made from the guira fruit, a utensil commonly used in Yucatán and other south-east Mexico states.

- ^ a b c "Denominación San Martín Huamelulpam" [San Martín Huamelulpam Denomination]. Enciclopedia de los municipios y delegaciones de México (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2011-05-17. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ Gaxiola, 2007.

- ^ Stephen A. Kowalewski and Andrew K. Balkansky. The survey area included 31 municipios of three districts of the state of Oaxaca: Tlaxiaco, Teposcolula and Nochixtlán, which covered a large territory between four previously surveyed regions of the Mixteca Alta (the Nochixtlán Valley, the Tilantongo-Jaltepec sector, the Huamelulpan Valley and the Teposcolula Valley).

- ^ Campbell (1997:402)

- ^ 2000 census; the numbers are based on the number of total population for each group and the percentages of speakers given on the website of the Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, http://www.cdi.gob.mx/index.php?id_seccion=660 Archived 2019-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 28 July 2008.

- ^ Arguments based on the now discredited method of glottochronology were abandoned from the 1960s on, but in the 1980s fresh research by Terrence Kaufman supports placing Cuicatec and Mixtec into their own subdivision. However, this research apparently remains unpublished. See Macaulay 1996:4–6.

- ^ According to the Summer Institute of Linguistics

- ^ "Zonas Arqueologicas Oaxaca Huamelulpan" [Oaxaca Archaeological Areas Huamelulpan]. Oaxaca Tourist Guide (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2010-11-29. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

References

edit- Acuña, René. 1984 Relaciones geográficas del siglo XVI: Antequera, Tomos Segundo y Tercero. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México.

- Álvarez, José J. y Rafael Durán. 1856 Itinerarios y derroteros de la República Mexicana. Biblioteca Nacional de México, México.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo. 2002. Palo Gordo, Guatemala, y el estilo artístico Cotzumalguapa. En Incidents of Archaeology in Central America and Yucatán: Essays in Honor of Edwin M. Shook (editado por M. Love, M. Hatch y H. Escobedo), pp. 147–178. University Press, Lanham, Maryland.

- Clark, John E. 1990 Olmecas, olmequismo y olmequización en Mesoamérica. Arqueología 3:49–56. México.

- Clark, John E. y Mary E. Pye (s.f.) Re-Visiting the Mixe-Zoque, Slighted Neighbors and Predecessors of the Early Lowland Maya. En Southern Maya in the Late Preclassic (editado por M. Love y R. Rosensweig), University of Colorado, Boulder.

2000 The Pacific Coast and the Olmec Question. En Olmec Art and Archaeology in Mesoamerica (editado por J. Clark y M. Pye), pp. 217–251. Studies in the History of Art 58. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. - Bovallius, Carl (1886). "Nicaraguan Antiquities". Swedish Society of Anthropology and Geography. Stockholm, Sweden. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- Covarrubias, Miguel 1957. Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

- De la Fuente, Beatriz 1995. Tetitla. En La pintura mural prehispánica en México, Teotihuacan (editado por B. De la Fuente), Vol.1, No.1, pp. 258–311. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México.

- Díaz del Castillo, Bernal 1976. Historia de la conquista de Nueva España, undécima edición. Editorial Porrúa, México.

- Ekholm-Miller, Susana 1973. The Olmec Rock Carving at Xoc, Chiapas, Mexico. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No.32. Brigham Young University, Provo.

- Graham, John A. 1981. Abaj Takalik: The Olmec Style and its Antecedents in Pacific Guatemala. En Ancient Mesoamerica: Selected Readings (editado por J. Graham), pp. 163–176. Peek Publications, Palo Alto, California.

- Grove, David C. 1996. Archaeological Contexts of Olmec Art Outside of the Gulf Coast. En Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico (editado por E. Benson y B. de la Fuente), pp. 105–117. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C..

- Gutiérrez, Gerardo 2002. The Expanding Polity: Patterns of the Territorial Expansion of the Post-Classic Señorío of Tlapa-Tlachinollan in the Mixteca-Nahua-Tlapaneca Region of Guerrero. Tesis de Doctorado, Departamento de Antropología, The Pennsylvania State University, State College. [1]

- Gutiérrez, Gerardo, Viola Köenig, and Baltazar Brito 2009. Codex Humboldt Fragment 1 (Ms. Amer. 2) and Codex Azoyú 2 Reverse: The Tribute Record of Tlapa to the Aztec Empire/Códice Humboldt Fragmento 1 (Ms.amer.2) y Códice Azoyú 2 Reverso: Nómina de tributos de Tlapa y su provincial al Imperio Mexicano. Bilingual (Spanish-English) edition. Mexico: CIESAS and Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Berlin). [2]

- Gutiérrez, Gerardo, and Constantino Medina 2008. Toponimia nahuatl en los codices Azoyú 1 y 2: Un estudio crítico de los nombres de lugar de los antiguos señoríos del oriente de Guerrero. [Nahuatl Toponymy in the Azoyú Codices 1 and 2: A Critical Study of the Placenames of the Ancient Lords of Eastern Guerrero]. Mexico: CIESAS. [3]

- Gutiérrez, Gerardo 2003. Territorial Structure and Urbanism in Mesoamerica: The Huaxtec and Mixtec-Tlapanec-Nahua Cases. In Urbanism in Mesoamerica, W. Sanders, G. Mastache and R. Cobean, (eds.), pp. 85–118. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University and INAH. [4]

- Gutiérrez, Gerardo, Alfredo Vera, Mary E. Pye, and Juan Mitzi Serrano 2011. Contlalco y La Coquera: Arqueología de dos sitios tempranos del Municipio de Tlapa, Guerrero. Mexico: Municipio de Tlapa de Comonfort, Letra Antigua. [5]

- Jiménez Moreno, Wigberto 1966. Mesoamerica Before the Toltecs. En Ancient Oaxaca (editado por J. Paddock), pp. 1–85. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- Miles, Susana W. 1965. Summary of Preconquest Ethnology of the Guatemala-Chiapas Highlands and Pacific Slopes. En Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol.2 (editado por G. Willey), pp. 276–287. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- Navarrete, Carlos 1978. The Prehispanic System of Communications Between Chiapas and Tabasco. En Mesoamerican Communication Routes and Cultural Contacts (editado por T. A. Lee, Jr. y C. Navarrete), pp. 75–106. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 40. Brigham Young University, Provo.

- Niederberger, Christine 2002. Nácar, "jade" y cinabrio: Guerrero y las redes de intercambio en la Mesoamérica Antigua (1000–600 a.C.). En El pasado arqueológico de Guerrero (editado por C. Niederberger y R. Reyna Robles), pp. 175–223. CEMCA, Gobierno de Estado de Guerrero e INAH, México.

- Paddock, John 1966. Oaxaca in Ancient Mesoamerica. En Ancient Oaxaca (editado por J. Paddock), pp. 86–242. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- Parsons, Lee A. 1981. Post-Olmec Stone Sculpture: The Olmec-Izapan Transition on the Southern Pacific Coast and Highlands. En The Olmec and Their Neighbors (editado por E. Benson), pp. 257–288. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

- Schieber de Lavarreda, Christa (ed) 1999. Taller arqueología de la región de la Costa Sur de Guatemala. Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, Guatemala.

- Stephen A. Kowalewski y Andrew K. Balkansky, 1999. Estudio Regional en la Mixteca Alta Central, Oaxaca, México

- Spores, Ronald 1993. Tutupec: A Postclassic-Period Mixtec Conquest State. Ancient Mesoamerica 4 (1):167-174.

- Urcid, Javier 1993. The Pacific Coast of Oaxaca and Guerrero: The westernmost Extent of Zapotec Script. Ancient Mesoamerica 4 (1):141-166.

- Balkansky, Andrew K. 1998. Urbanism and Early State Formation in the Huamelulpan Valley of Southern Mexico. Latin American Antiquity. Vol 9 No. 1, pp. 37–67 [6] Dec 2007

- Christensen, Alexander F. 1998. Colonization and Microevolution in Formative Oaxaca, Mexico, World Archaeology, Vol 30, 2 pp. 262–285 [7] Dec 2007

- Coll Hurtado, Atlántida 1998. Oaxaca: geografía histórica de la grana cochinilla, Boletín de Investigaciones Geográficas. Vol. 38 pp. 71–81 [8][permanent dead link] March 2007

- Dalghren de Jordán, Barbro (1966): La Mixteca, su cultura e historia prehispánicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México.

- Flannery Kent V. y Joyce Marcus (2007): "Las sociedades jerárquicas oaxaqueñas y el intercambio con los olmecas", en Arqueología Mexicana, (87): 71–76, Editorial Raíces, México.

- Gaxiola González, Margarita (2007), "Huamelulpan, Oaxaca", en Arqueología Mexicana, (90): 34–35, Editorial Raíces, México.

- Michel Graulich (2003), "El sacrificio humano en Mesoamérica", en Arqueología Mexicana, (63): 16-21.

- Hosler, Dorothy (1997), "Los orígenes andinos de la metalurgia del occidente de México", en el sitio en internet de la Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango del Banco de la República de Colombia, consultado el 31 de enero de 2010.

- Jansen, Maarten (1992), "Mixtec Pictography: Contents and Conventions", en Reifler Bricker, Victoria (ed.): Epigraphy. Supplement to the Handbook of Middle-American Indians, University of Texas Press, 20–33, Austin.

- Jansen, Maarten y Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez (2002), "Amanecer en Ñuu Dzavui", en Arqueología mexicana, (56): 42–47, Editorial Raíces, México.

- Josserand, J. Kathryn; Maarten Jansen y Ángeles Romero (1984), "Mixtec dialectology: inferences from Linguistics and Ethnohistory", en J. K. Josserand, Marcus C. Winter y Nicholas A. Hopkins (eds.), Essays in Otomanguean Culture and History, Vanderbilt University Publications in Anthropology, 119–230, Nashville.

- Joyce, Arthur A. y Marc N. Levine (2007)", Tututepec (Yuca Dzaa). Un imperio del Posclásico en la Mixteca de la Costa", en Arqueología Mexicana, (90): 44–47, Editorial Raíces, México.

- Joyce, Arthur A. y Marcus Winter (1996), "Ideology, Power, and Urban Society in Pre-Hispanic Oaxaca", en Current Anthropology, 37(1, feb. 1996): 33–47, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Justeson, John S. 1986. The Origin of Writing Systems: Preclassic Mesoamerica, World Archaeology. Vol. 17 nos. 3. pp. 437–458 [9] Dec. 2007

- Lind, Michael (2008), "Arqueología de la Mixteca", en Desacatos, (27): 13–32.

- Maldonado, Blanca E. (2005): "Metalurgia tarasca del cobre en el sitio de Itziparátzico, Michoacán, México", en el sitio en internet de FAMSI, consultado el 31 de enero de 2010.

- Marcus, Joyce (2001): "Breaking the glass ceiling: the strategies of royal women in ancient states", en Cecelia F. Klein (ed.), Gender in Pre-Hispanic America, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Oudijk, Michel R. (2007), "Mixtecos y zapotecos en la época prehispánica", en Arqueología Mexicana, (90): 58–62, Editorial Raíces, México.

- Paddock, John (1990): "Concepción de la idea Ñuiñe", en Oaxaqueños de antes, Oaxaca Antiguo A.C. y Casa de la Cultura Oaxaqueña, Oaxaca de Juárez.

- Pye, Mary E., and Gerardo Gutiérrez 2007. The Pacific Coast Trade Route of Mesoamerica: Iconographic Connections between Guatemala and Guerrero. In Archaeology, Art, and Ethnogenesis in Mesoamerican Prehistory: Papers in Honor of Gareth W. Lowe, L. Lowe and M. Pye (eds.), pp. 229–36. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No.68. Brigham Young University, Provo.

- Rivera Guzmán, Ángel Iván (1998): "La iconografía del poder en los grabados del Cerro de La Caja, Mixteca Baja de Oaxaca", en Barba de Piña Chan, Beatriz (ed.), Iconografía mexicana, Plaza y Valdés-INAH, México.

- Rossell, Cecilia y María de los Ángeles Ojeda Díaz (2003), Mujeres y sus diosas en los códices preshispánicos de Oaxaca, CIESAS-Miguel Ángel Porrúa, México.

- Villela Flores, Samuel (2006), "Los estudios etnológicos en Guerrero", en Diario de Campo, (38, agosto 2006): 29–44, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

- Spores, Ronald (1967), The Mixtec Kings and Their People, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- ------- (2007), "La Mixteca y los mixtecos. 3000 años de adaptación cultural", en Arqueología Mexicana, (90): 28–33, Editorial Raíces, México.

- Terraciano, Kevin (2001), The Mixtecs of colonial Oaxaca: Nudzahui history, sixteenth through eighteenth centuries, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Further reading

edit- The Mixtecs of Colonial Oaxaca: Ñudzahui History, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries, Kevin Terraciano, Stanford University Press, 2001

- The Mixtec Kings and Their People, Ronald Spores, University of Oklahoma Press, 1967

- The Cloud People: Divergent Evolution of the Mixtec and Zapotec Civilizations, Flannery, K. and Marcus, J. (eds.), Percheron Press, 2003.

- Stories in Red and Black: Pictorial Histories of the Aztec and Mixtec, Boone, E. H., University of Texas Press, 2000.

- Presencias de la Cultura Mixteca (Memorias de la Primera Semana de la Cultura Mixteca), Ignacio Ortiz Castro (ed.), Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca, 2002. (in Spanish)

- La Tierra del Sol y de la Lluvia (Memorias de la Segunda Semana de la Cultura Mixteca), Ignacio Ortiz Castro (ed.), Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca, 2003. (in Spanish)

- Personajes e Instituciones del Pueblo Mixteco (Memorias de la Tercera Semana de la Cultura Mixteca), Ignacio Ortiz Castro (ed.), Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca, 2004. (in Spanish)

- Pasado y Presente de la Cultura Mixteca (Memorias de la Cuarta Semana de la Cultura Mixteca), Ignacio Ortiz Castro (ed.), Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca, 2005. (in Spanish)

- Nuu Savi (Nuu Savi – Pueblo de Lluvia), Miguel Ángel Chávez Guzman (compilador), Juxtlahuaca.org, 2005. (in Spanish)

- Joyce, Arthur A. (2010). Mixtecs, Zapotecs and Chatinos: Ancient peoples of Southern Mexico. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20977-5.