Horus Sa (also Horus Za, Sa and Za) was a possible early Egyptian pharaoh who may have reigned during the Second or Third Dynasty of Egypt. His existence is disputed, as is the meaning of the artifacts that have been interpreted as confirming his existence.

| Horus Sa | |

|---|---|

| Weneg ? Senedj ? Sanakht ? | |

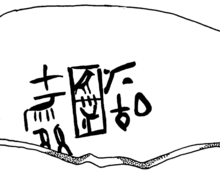

Vessel fragment bearing the inscription Ḥwt-k3 Ḥrw-z3. | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | 2nd or 3rd Dynasty |

| Burial | uncertain, gallery tomb at Saqqara ?, Gisr el-mudir ? |

Attestations

editHorus Sa is known from vessel fragments with black ink inscriptions showing his name. These vessels were found in the east galleries beneath Djoser's pyramid at Saqqara. The inscriptions are short and written in cursive handwritings. In all cases the name "Horus Sa" does not appear within a serekh and its identification as the Horus-name of a king is disputed.[1][2]

The name "Horus Sa" always appears within the inscription Ḥwt-k3 Ḥrw-z3 ("House of the Ka of Horus Sa"), regularly found together with the names of Inykhnum and Ma'a-aper-Min, two high-ranking officials who served in the Ka-house. During the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt, the House of the Ka was a forerunner of the mortuary temple, a place where a cult to the Ka of a deceased ruler was performed. A further inscription, Ḥwt-k3 Ḥrw-z3, was found in the 1980s at Saqqara in the area of the tomb of Maya and very close to that of Meryra-Meryneith.[3] Maya and Meryra-Meryneith were both late 18th dynasty court officials who reused 2nd dynasty tombs for themselves, some 1,500 years after the death of their original owners.[3][4]

Identity

editJürgen von Beckerath, Dietrich Wildung and Peter Kaplony proposed that "Sa" is a short form of the Horus-name Sanakht.[5] Wolfgang Helck rejects this argument on the grounds that the ink inscriptions from the east-galleries of Djoser's pyramid complex date predominantly from the reign of Nynetjer or shortly thereafter, while Sanakht reigned during the mid-3rd dynasty. Furthermore, inscriptions mentioning the "House of the Ka of Hotepsekhemwy" are stylistically similar to that of Horus Sa which would place Sa in the 2nd dynasty since Hotepsekhemwy was the first ruler of that dynasty. Thus, Helck proposed that Horus Sa is the Horus-name of another shadowy ruler of the 2nd dynasty, Weneg, whose Horus-name is otherwise unknown.[6]

The Egyptologist Jochem Kahl recently challenged this hypothesis, identifying Weneg with Raneb.[7] Alternatively, Kaplony reconstructed the Horus-name of Weneg from the Cairo fragment of the Palermo stone as Wenegsekhemwy.[8] In both cases, Horus Sa cannot be the Horus-name of Weneg and the two would not designate the same king. Consequently, Kaplony equated Horus Sa with njswt-bity Wr-Za-Khnwm, "The king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Wersakhnum" and credited him a reign of 2 months and 23 days during the interregnum between Khasekhemwy and Djoser.[9] However, Kaplony's hypothesis has been undermined by the discovery of clay seals of Djoser in Khasekhemwy's tomb, indicating that the former immediately succeeded and buried the latter.[10] Horus Sa could instead be the Horus-name of Senedj or another 2nd dynasty king, ruling in Memphis during the troubled period following the reign of Nynetjer.[11]

However, Egyptologists such as Jean-Philippe Lauer, Pierre Lacau and Ilona Regulski call for caution of the correct reading of the inscriptions. Especially the bird-sign at the top of the Ka-house might also depict a swallow, which would make the inscription to be read as Wer-sa-hut-Ka ("great protection of the Ka-house"). Regulski prefers the reading as a Horus-bird, though she doesn't explicitly see it as the name of a king. She dates the inscriptions to the end of Khasekhemwy's reign.[1]

Tomb

editThe burial place of Horus Sa is unknown. Nabil Swelim associated Horus Sa with the unfinished enclosure of Gisr el-Mudir in west Saqqara.[12] This hypothesis has not gained wide acceptance and the Gisr el-Mudir has been attributed to various second dynasty kings, in particular Khasekhemwy.[13] Alternatively, the Egyptologist Joris van Wetering proposed that the gallery tomb used by the high priest of Aten, Meryra-Meryneith, in north Saqqara was originally that of Horus Sa, since an inscription Ḥwt-k3 Ḥrw-z3 was found in the close vicinity of the tomb.[3][4]

Further reading

edit- Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen, Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3

- Pierre Lacau & Jean-Philippe Lauer: La Pyramide à Degrés V. – Inscriptions Gravées sur les Vases: Fouilles à Saqqarah, Service des antiquités de l'Égypte, Kairo 1936

- Wolfgang Helck: Untersuchungen zur Thinitenzeit. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-447-02677-4

- Nabil Swelim: Some Problems on the History of the Third Dynasty, Archaeology Society, Alexandria 1983

- Ilona Regulski: Second dynasty ink inscriptions from Saqqara paralleled in the Abydos material from the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels. In: Stan Hendrickx, R.F. Friedman, Barbara Adams & K. M. Cialowicz: Egypt at its origins. Studies in memory of Barbara Adams. Proceedings of the international Conference „Origin of the State, Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt“, Kraków, 28th August – 1st September 2002 (= Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Vol. 138). Peeters Publishers, Leuven (NL) 2004, ISBN 90-429-1469-6.

References

edit- ^ a b Ilona Regulski: Second dynasty ink inscriptions from Saqqara paralleled in the Abydos material from the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels. pp. 953–959.

- ^ Wolfgang Helck, Die Datierung der Gefäßaufschriften aus der Djoserpyramide, in: Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 106, 1979, ISSN 0044-216X, pp. 120–132.

- ^ a b c Joris van Wetering: The Royal Cemetery of the Early Dynastic Period at Saqqara and the Second Dynasty Royal Tombs, in Proceedings of the Krakow Conference, 2002.

- ^ a b René van Walsem, Sporen van een revolutie in Saqqara. Het nieuw ontdekte graf van Meryneith alias Meryre en zijn plaats in de Amarnaperiode, Phoenix : bulletin uitgegeven door het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux, 47 (1-2), pp. 69-89.; see also M. J. Raven and R. Walsem: Preliminary report on the Leiden Excavations at Saqqara, 2001, 2003, 2004, 2007, Complete list Archived 17 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen, p. 243.

- ^ Wolfgang Helck: Untersuchungen zur Thinitenzeit, p. 103 and 108.

- ^ Jochem Kahl, Ra is my Lord - Searching for the rise of the Sun God at the dawn of Egyptian history, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 3-447-05540-5, pp. 12–14 & 74.

- ^ Peter Kaplony: Steingefässe mit Inschriften der Frühzeit und das Alten Reiches. Monographies Reine Elisabeth, Bruxelles 1968

- ^ Peter Kaplony: Die Inschriften der Ägyptischen Frühzeit. O. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1963, pp. 380, 468 & 611.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, p. 83 & 95

- ^ Thomas Von der Way: Zur Datierung des "Labyrinth-Gebäudes" auf dem Tell el-Fara'in (Buto), in: Göttinger Miszellen 157, 1997, 107-111

- ^ Nabil Swelim: Some Problems on the History of the Third Dynasty, p. 33 and 181−182.

- ^ Ian Mathieson, Elizabeth Bettles, Joanne Clarke, Corinne Duhig, Salima Ikram, Louise Maguire, Sarah Quie, Ana Tavares: The National Museums of Scotland Saqqara Survey Project 1993–1995. In: Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 83, 1997, S. 17–53, hier S.36, 38ff., 53.