Holland House, originally known as Cope Castle, was an early Jacobean country house in Kensington, London, situated in a country estate that is now Holland Park. It was built in 1605 by the diplomat Sir Walter Cope. The building later passed by marriage to Henry Rich, 1st Baron Kensington, 1st Earl of Holland, and by descent through the Rich family, then became the property of the Fox family, during which time it became a noted gathering-place for Whigs in the 19th century. The house was largely destroyed by German firebombing during the Blitz in 1940 and today only the east wing and some ruins of the ground floor and south facade remain, along with various outbuildings and formal gardens. In 1949 the ruin was designated a grade I listed building[1] and it is now owned by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

| Holland House | |

|---|---|

Holland House in 1896 and its remains in 2014 | |

| Location | London |

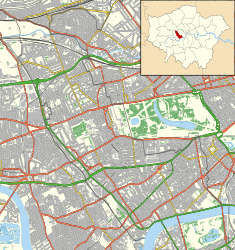

| Coordinates | 51°30′9.7″N 0°12′8.2″W / 51.502694°N 0.202278°W |

| Built | 1605 |

| Built for | Sir Walter Cope |

| Architectural style(s) | Jacobean |

| Owner | Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 29 Jul 1949[1] |

| Reference no. | 1267135 |

17th century

editCope commissioned the house in 1604 from the architect John Thorpe,[a] to preside over a 500 acres (200 ha; 0.78 sq mi) estate that, in modern terms, stretched from Holland Park Avenue almost to Fulham Road,[3] and contained exotic trees imported by John Tradescant the Younger.[4] Following its completion, Cope entertained the king and queen at it numerous times; in 1608, John Chamberlain, the noted author of letters, complained that he "had the honour to see all, but touch nothing, not so much as a cherry, which are charily preserved for the queen's coming."[5]

Cope was a cousin of Dudley Carleton, the English ambassador in Venice. The Venetian ambassador in London, Antonio Foscarini, cultivated Cope and visited his house in Kensington.[6] In November 1612 James I, following the death of his eldest son Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, spent the night at Cope Castle. He was joined the following day by his son Prince Charles and daughter Princess Elizabeth, and her fiancé Frederick V, Elector Palatine.[7]

Cope died in 1614 without a son. The house was inherited by his daughter Isabel Cope, who in 1616, two years after her father's death, married Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland, whose property it then became. Rich was granted the titles of Baron Kensington and Earl of Holland by James I, and upon gaining the latter renamed the building to Holland House.[8] In 1649 Rich was beheaded for his Cavalier activities during the English Civil War and the house was then used as an army headquarters, being regularly visited by Oliver Cromwell.

Following the death of Henry Rich, his eldest son Robert Rich, the second Earl of Holland, inherited the house, and in 1673 succeeded his first cousin as fifth Earl of Warwick, which is commemorated locally by Warwick Road and Warwick Gardens to the southwest of Holland House.[9] The house and titles of Rich, Warwick, and Holland passed from him to his son Edward Rich.

William III

editKing William III (1689–1702) considered moving to Holland House for health reasons. He had been a lifelong sufferer from asthma, which condition was exacerbated by the damp air at the riverside location of the Palace of Whitehall.[10] In 1689, attempting to improve his health, he decided to move his court. After a short time spent at Hampton Court, he decided to find another home that was near enough to the capital to easily carry out royal business, but far enough away from the air of London not to threaten his health. He considered Holland House for the purpose, and stayed there for some weeks. Several of his letters are dated from Holland House.[11] Eventually he purchased nearby Kensington House, the residence of Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham, which became Kensington Palace.

18th century

editJoseph Addison

editIn 1697 Edward Rich had married Charlotte Myddelton, the only child of Sir Thomas Myddelton, 2nd Baronet of Chirk Castle, Denbighshire. She survived him at his death in 1701, and in 1716 remarried to the celebrated writer Joseph Addison. Addison lived at Holland House after his marriage, which was not a happy one, and died there three years later in 1719.[12] Among his favoured venues for spending his leisure hours was the White Horse Inn, sited at the entrance of the back lane to Holland House.[13] A century later Addison Avenue, Crescent, Gardens, Place, and Road on the § Ilchester Estate west of Holland Park were named after him.

Edwardes family

editOwnership of the house passed from the sixth Earl to his son Edward Henry Rich, 4th Earl of Holland, 7th Earl of Warwick. He died in 1721 aged 23, childless and unmarried, a decade before his mother.[14] His titles, but not his estates, were inherited by his cousin Edward Henry Rich, while the house was inherited by his aunt Lady Elizabeth Rich, who was married to Francis Edwardes of Pembrokeshire, Wales,[3] whose family owned extensive lands in Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire, and Ceredigion.[15] On his death in 1725 Holland House passed to his son Edward Henry Edwardes, who in turn at his death in 1737 bequeathed the house to his brother William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington,[16] subject to a long entail.[3] Edwardes followed his father in being Member of Parliament for Haverfordwest, and was elevated to the Peerage of Ireland as Baron Kensington in 1776.

Fox family

editDespite owning Holland House, neither William Edwardes nor any of his family appear to have lived in it.[3][b] In 1746 he let the house and sixty-four acres of land to his parliamentary colleague Henry Fox – a leading Whig politician who would later be created Baron Holland – for 99 years or three lives.[3]

By 1767, Fox was leasing all of Edwardes' estate north of the Hammersmith road (the modern Kensington High Street), and in 1768 completed the purchase of the 200 acres[3] of land for £17,000, with a further £2,500 paid in compensation to Rowland Edwardes and John Owen Edwardes, the beneficiaries of the entail established by Edward Henry Edwardes.[c] A private Act of Parliament (8 Geo. 3. c. 32) was obtained to break the entail and confirm the conveyance.[3] The sale included the lordship of the manor of Abbots Kensington, and situated on the estate was Little Holland House, the dower house, with two or three more minor houses and a tavern.[3] Between 1762 and 1768 Lord Holland built for his retirement a large country house at Kingsgate in Kent. Fox died at Holland House in 1774, whereupon his title passed to his son Stephen, but Stephen died only five weeks later.

Stephen and his wife Lady Mary FitzPatrick had had two children. Caroline was born in 1767, and whilst living at Little Holland House in 1842, she founded a charity school, known today as Fox Primary School.[18] Her brother Henry was born in 1773, and became the third Baron when his father died. In 1797 he married Elizabeth Vassell, who became Baroness Holland. She died in 1845 and the estate passed to their son Henry Fox, 4th Baron Holland.[3]

19th century

editDevelopment of estate

editHenry Fox undertook a series of residential developments on the estate, using them as collateral to raise loans to finance the family's lifestyle, the expenses of which exceeded their income.[3] In a letter dated 13 May 1823, he referred to the marking out of the future Addison Road as an "important profitable but melancholy occupation", and in 1824 he mentioned the "tremendous and I hope... profitable works" then being undertaken. Lady Holland was circumspect of the beneficial prospects, writing to him in the same year that "remote posterity may benefit because for some generations it must be tightly mortgaged... none now alive will be much bettered by the undertaking."[3] In 1849, he mortgaged Holland House and its grounds to pay for the development of roads and sewers.[3] He died in 1859 without issue, causing the title of Baron Holland to expire, and ownership of the estate passed to his wife, Lady Mary Augusta Coventry, a daughter of George Coventry, 8th Earl of Coventry. Facing pressures in her life, Lady Holland sold much of the estate in the years that followed her husband's death,[3] and eventually in 1874 sold Holland House to a distant relative of her husband: Henry Fox-Strangways, 5th Earl of Ilchester, the descendant of the first Earl, Stephen Fox-Strangways, the elder brother of Henry Fox, the first Baron Holland. As part of the terms of sale he allowed Lady Holland to continue living in the house, as well as granting her an annuity for life of £6,000.[3]

Whig social centre

editThe first Baron Holland's second son Charles James Fox[d][19] was a Whig statesman. During his life, Holland House became a glittering social, literary and political centre, and the social centre of the Whig party, with his nephew, the third Baron, acting as host for his Whig dinners. Following his death in 1806, a statue of him was placed in the house's hall.[20]

Celebrated visitors to the house included the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, the poets Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell, and Samuel Rogers, the politicians Lord Melbourne, Lord John Russell, Richard "Conversation" Sharp and Benjamin Disraeli, and the writers Charles Greville, Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott, as well as Joseph Blanco White,[21] a Spaniard who moved to Britain. The political and historical writer John Allen was so much associated with the house that he was known as "Holland House Allen", and a room in the house was named after him.[4] Lady Caroline Lamb, who had first met her lover Lord Byron at Holland House, satirised it in her 1816 novel Glenarvon.[20]

...this strange house, which presents an odd mixture of luxury and constraint, of enjoyment both physical and intellectual, with an alloy of small désagréments.... Though everybody who goes there finds something to abuse or ridicule in the mistress of the house, or its ways, all continue to go; all like it more or less; and whenever, by the death of either, it shall come to an end, a vacuum will be made in society which nothing will supply. It is the house of all Europe; the world will suffer by the loss; and it may be said with truth that it will "eclipse the gayety of nations".

— Charles Greville, The Greville Memoirs[22]

The prestige of Holland House during the period extended to British colonies. In 1831 Henry John Boulton, who was born in Holland House, erected a baronial-like home in the city of Toronto. Henry John Boulton had been born in the famous English house, and he commemorated that fact by naming the Toronto home Holland House.[23]

Henry Fox-Strangways

editWhen Henry Fox-Strangways inherited Holland House in 1874, he was living in Melbury House in Melbury Sampford, Dorset, where he owned large estates. It appears that the Earl was "in part motivated by the desire to preserve Holland House and its grounds from speculators", but had taken on financial burdens together with his inheritance which needed to be mitigated. He immediately made plans to develop part of the land to the west of Holland House, which became Melbury Road, named after his Dorset seat. Lady Holland, still living in Holland House, had objected and wrote that "all the building is a very bitter and sad pill to me".[24] After her death in 1889, he moved into Holland House.[24] Most of the already developed land had been let on long leases not expiring until 1904, after which he had scope to effect further development.

20th century

editIlchester Estate

editGiles Fox-Strangways, 6th Earl of Ilchester inherited the house in 1905. During his ownership much of the land to its west was developed for housing as the Ilchester Estate, including Ilchester Place, completed in 1928,[24] Abbotsbury Road (now forming the western boundary of Holland Park), named after Abbotsbury Abbey in Dorset, acquired in 1543 by Sir Giles Strangways[25] at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and several roads named after § Joseph Addison.[e]

Partial destruction in the Blitz

editIn 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended the debutante ball of Rosalind Cubitt, the last great ball held at the house.[26][27] The following year, on 7 September, the German bombing raids on London, the Blitz, began. During the night of 27 September, Holland House was hit by twenty-two incendiary bombs during a ten-hour raid. The house was largely destroyed, with only the east wing, and, miraculously, almost all of the library remaining undamaged. Surviving volumes included the sixteenth-century Boxer Codex.

Post-war preservation

editHolland House was designated Grade I listed building status in 1949[1] under the auspices of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947; the Act sought to identify and preserve buildings of special historic importance, prompted by the damage caused by wartime bombing.[28] The building remained a burned-out ruin until 1952, at which point the 6th Earl sold the house and fifty-two acres to London County Council (LCC) for £250,000.[24] The remains of the building passed from the LCC to its successor the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1965, and upon the dissolution of the GLC in 1986 to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

The 6th Earl died in 1959, and his remaining interest in the estate passed to his son Edward Henry Charles James Fox-Strangways, 7th Earl of Ilchester who in 1962 sold a piece of land immediately to the south of what is now the sports field for the construction of the Commonwealth Institute. Following the 7th Earl's death in 1964 the estate passed to his only daughter, Lady Theresa Jane Fox-Strangways. The family retains the developed land adjoining the west side of Holland Park.[f]

Today, the remains of Holland House form a backdrop for the open air Holland Park Theatre, home of Opera Holland Park. The YHA (England and Wales) "London Holland Park" youth hostel was located in the house but has now closed. The Orangery is now an exhibition and function space, with the adjoining former Summer Ballroom now a restaurant, The Belvedere. The former ice house is now a gallery space. The grounds provide sporting facilities, including a cricket pitch, football pitch, and six tennis courts.

Design and grounds

editThe building was of a common shape for large houses of the time,[30] containing a centre block and two porches.[31] The building received a large expansion between 1625 and 1635 at the direction of the first Earl of Holland, who added two wings and arcades.[31]

The house had a Great Chamber which became known as the "Gilt Chamber". This central reception room was reworked with three stone arches provided by the master mason Nicholas Stone in 1632.[32] The decoration is often attributed to the German-born artist Francis Cleyn,[33][34] but documentation shows the decorator was Rowland Bucket.[35] The scheme included "figures over the fireplace were painted in flesh colour wherever bare; the rest was in shaded gold. The lower marbles of the fireplace were black, and the upper ones were Sienna; the capitals and bases of the columns and pilasters were gilt, and the groundwork from which all the glittering decoration rose was white."[36] It carried decorations of the coats of arms of the Cope and Rich families. Rowland Bucket also provided carved and gilded chairs for the room, thought to be in Italianate style, and Cleyn may have designed these and other carved features for Bucket.[37] Later, numerous busts were displayed in niches in the gilt chamber, many by Joseph Nollekens, with subjects including the first Lord Holland, Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, Francis Russell, 5th Duke of Bedford, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, Napoleon, the Italian poet Ludovico Ariosto, Henry IV of France, King George IV, and Charles James Fox. Portraits in the room included the Lennox, Digby, and Fox families, and a portrait by Joshua Reynolds of Charles James Fox as a boy with his first cousin Lady Susan Strangways and his aunt Lady Sarah Lennox.[g]

Holland bought tapestry from the Mortlake Works for his new rooms. As a retreat from the heat of summer, there was a basement grotto, possibly the work of Nicholas Stone in the 1630s.[39] Holland began a second campaign of building in 1637 with a new west wing (demolished in 1702) with grand stables and a coach house. These works may have been designed by Isaac de Caus.[40]

In 1629, Holland commissioned Inigo Jones[42] to design and the master mason Nicholas Stone to carve a pair of Portland stone piers, in order to support large wooden gates for the house.[h] The piers, still extant, take the form of Doric columns on pedestals, and originally supported carved griffins bearing the arms of the Rich family and Cope family, symbolising the two families' union.[45] The piers have been moved to new positions on several occasions. While their exact original position is not known, a survey in 1694 showed them as being on the drive leading to the house's main entrance on its south side. In 1848, the 4th Baron Holland moved them to the east side to be an entrance to the pleasure grounds, and on the south front created a terrace enclosed by a low balustrade. In place of the original entrance hall on the south side he created a "breakfast room".[46] Following the house's § partial destruction in the Blitz, and the conversion in 1959 of the remains of the east wing into a youth hostel, the piers were returned to the south side.[45]

The house's dower house, known as Little Holland House, became the centre of a Victorian artistic salon presided over by the Prinseps and the painter George Frederic Watts.

In 1804 the garden of Holland House saw one of the earliest successful growths of the dahlia in England. Whilst in Madrid, Lady Holland was given either dahlia seeds or roots by botanist Antonio José Cavanilles.[47] She sent them back to England, to Lord Holland's librarian Mr Buonaiuti at Holland House, who successfully raised the plants.[48][49]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Holland House had the largest private grounds of any house in London, including Buckingham Palace.[31] The Royal Horticultural Society regularly held flower shows there.

Timeline of ownership

editLondon County Council, Greater London Council, and Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Galleries

edit-

The south frontage of Holland House

-

The China Room

-

The Dutch Garden

-

A garden with a fountain on the house's west side

-

The north side of the house viewed from its lawn

-

Steps to a garden

-

The Gilded Room, or Gilt Chamber

-

The library

-

The arcade, originally part of the old stables

-

An arcade of roses

-

The main staircase

-

The Swaneries Drawing Room

-

A garden terrace with steps on the house's east side

Notes

edit- ^ The book of Thorpe's designs is held by Sir John Soane's Museum, containing a ground-plan of the mansion with the identification "Sir Walter Coapes at Kensington, perfected per me I. T."[2]

- ^ The family is commemorated in name locally by Edwardes Square, a garden square built in 1811 by William Edwardes, 2nd Baron Kensington to the immediate south-west of Holland House.[17]

- ^ The Survey of Kensington suggests that Fox was able to pay this sum with profits obtained from his office of Paymaster General during the Seven Years' War.[3]

- ^ Charles James Fox was born in 1749 at No. 9 Conduit Street, while Holland House was being redecorated.

- ^ The 6th Earl wrote several works on Holland House; see § Further reading

- ^ Together with its Dorset properties, the Fox-Strangways family trades as "Ilchester Estates".[29]

- ^ In 1760 whilst at Eton College, Charles had developed a schoolboy crush on Susan and composed a prize-winning Latin verse describing a pigeon he found to deliver his love-letters to her "to please both Venus its mistress and him".[38]

- ^ In a notebook of engraver George Vertue (designated "A.b" [43]), who compiled a history of art in the country, he records "Kensington, 23 March 1629. Nicholas Stone undertakes to [make] for the Earl of Holland 2 Peeres of good Portland stone to hang a pair of great wooden gates on for £100."[44][42]

Citations

edit- ^ a b c Historic England 2015.

- ^ Sanders 1908, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Sheppard 1973, p. 101.

- ^ a b Allen 2004.

- ^ Birch & Williams 1848, p. 75.

- ^ Birch & Williams 1848, p. 187.

- ^ Birch & Williams 1848, p. 205.

- ^ Webb 1921, pp. 292–296.

- ^ Thornbury 1874.

- ^ Historic Royal Palaces 2012.

- ^ Macaulay 1848, p. 63.

- ^ Walford 1878.

- ^ Faulkner 1820, p. 118.

- ^ National Trust 2019.

- ^ History of Parliament 1970.

- ^ History of Parliament 1964.

- ^ London Gardens Online 2012.

- ^ Sheppard 1973, p. 127.

- ^ Lascelles 1936, p. 3.

- ^ a b Ridley 2013.

- ^ Liechtenstein 1875, p. 91.

- ^ Greville 1887, p. 126.

- ^ Robertson 1894.

- ^ a b c d Sheppard 1973, p. 126.

- ^ Page 1908.

- ^ MacCarthy 2006, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Mitford 2010, p. 97.

- ^ Victorian Society 2013.

- ^ W. A. Ellis 2012.

- ^ Walford 1878, pp. 161–177.

- ^ a b c Mitton 1903.

- ^ Cooper 2020, p. 57.

- ^ Fell-Smith 1909.

- ^ Neale 1828.

- ^ Cooper 2020, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Harper's 1877, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Cooper 2020, p. 60.

- ^ Lascelles 1936, p. 11.

- ^ Cooper 2020, pp. 62–3.

- ^ Cooper 2020, pp. 63–9.

- ^ Liechtenstein 1875, p. 175.

- ^ a b Spiers 1919, p. 8.

- ^ Lindsay 1997, p. 242.

- ^ Vertue 1713.

- ^ a b Nolan & Starren 2010.

- ^ Liechtenstein 1875, p. 167.

- ^ Forbes & Russell Bedford 1833, p. 246.

- ^ Hogg 1853, p. 5.

- ^ Salisbury 1808, p. 93.

References

editBiographies

edit- Allen, Elizabeth (23 September 2004). "Cope, Sir Walter (1553?–1614)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6257. Retrieved 1 June 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Fell-Smith, Charlotte (1909). John Dee (PDF). London: Constable & Co Ltd. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Lascelles, Edward (1936). The Life of Charles James Fox. London: Oxford University Press.

- Sedgwick, Romney R., ed. (1970). "EDWARDES, Francis (d.1725), of Johnston, nr. Haverfordwest, Pemb.". The House of Commons 1715-1754. The History of Parliament. Vol. 2: Members E–Y. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Namier, Lewis; Brooke, John, eds. (1964). "EDWARDES, William (c.1712-1801), of Johnston, Pemb.". The House of Commons 1754-1790. The History of Parliament. Vol. 2: Members A–J. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Spiers, Walter Lewis (1919). Finberg, A. J. (ed.). "Notes on the life of Nicholas Stone". The Walpole Society. 7, The Note-book and Account-book of Nicholas Stone, Master Mason to James I and Charles I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

Histories

edit- Birch, Thomas; Williams, Robert Folkestone (1848). The Court and times of James the First: illustrated by authentic and confidential letters, from various public and private collections. Vol. 1. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- Faulkner, Thomas (1820). History and Antiquities of Kensington. London. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Greville, Charles (1887). "Chapter XIX". The Greville Memoirs: A Journal of the Reigns of King George IV. and King William IV. Vol. 2. Forgotten Books. ISBN 9781451016901. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- Liechtenstein, Princess Marie (1875). Holland House (3 ed.). London: Macmillan. OL 25199401M.

- Lindsay, Alexander (1997). Index of English Literary Manuscripts. Vol. 3, John Gay—Ambrose Philips. London: Mansell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7201-2283-X.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1848). "XI". The History Of England From the Accession of James II. Vol. III. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- MacCarthy, Fiona (5 October 2006). Last Curtsey: The End of the Debutantes. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0571228591.

- Mitton, Geraldine Edith (1903). "The Kensington District". In Sir Walter Besant (ed.). The Fascination of London. London: Adam & Charles Black. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Page, William, ed. (1908). "Houses of Benedictine monks: The abbey of Abbotsbury". A History of the County of Dorset. Vol. 2. Victoria County History. pp. 48–53. Retrieved 28 March 2019 – via British History Online.

- Ridley, Jane (6 April 2013). "Review: Holland House: A History of London's Most Celebrated Salon, by Linda Kelly". The Spectator. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

Holland's dinners kept the Whig party alive during long years of opposition, and by opening his doors to new talent and new ideas, he ensured that the party didn't stand still.

- Sanders, Lloyd Charles (1908). The Holland House Circle. London: Methuen & Co. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Sheppard, F. H. W., ed. (1973). Northern Kensington. Survey of London. Vol. 37. London: British History Online. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- Thornbury, George Walter (1874). Old and New London: a Narrative of its History, its People, and its Places.

- Walford, Edward (1878). "Holland House, and its Historical Associations". Old and New London. Vol. 5. British History Online. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Webb, E. A. (1921). "The parish: Descendants of Rich and the advowson". The records of St. Bartholomew's priory [and] St. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield. Vol. 2. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

Art and architecture

edit- "Elizabethan and later English furniture". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 56 (331). New York: Harper & Brothers: 22. December 1877. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Cooper, Nicholas (30 December 2020). "Holland House: Architecture in an Elite Society". Architectural History. 63. Cambridge University Press: 37–75. doi:10.1017/arh.2020.2. S2CID 229716135. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Historic England. "Holland House (1267135)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "Origins: From Jacobean mansion to Kensington Palace". Historic Royal Palaces. 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- "Edwardes Square". London Gardens Online. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "Charlotte Myddelton, Countess of Warwick (1680-1731)". National Trust. 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- Neale, John Preston (1828). "Holland House, Middlesex". Views of the Seats of Noblemen and Gentlemen, in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Vol. 4.

- Nolan, David; Starren, Caroline (2010). "On Public View: A journey around the sculpture of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea" (PDF). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Robertson, John Ross (1894). "3: The History of Holland House". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto. Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "Listed buildings". The Victorian Society. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Vertue, George (1713). Common-place books of G. Vertue. Vol. 2. Add MS 23068-23074. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

Other works

edit- Forbes, James; Russell Bedford, John (1833). Hortus Woburnensis, A Descriptive Catalogue of upwards of Six Thousand Ornamental Plants Cultivated at Woburn Abbey. J. Ridgway.

- Salisbury, R. A. (5 April 1808). "Observations on the different Species of Dahlia, and the best Method of Cultivating them in Britain". Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London. 1. London: W. Bulmer & Co.

- Hogg, Robert (1853). The Dahlia; Its History and Cultivation. Groombidge and Sons.

- "Ilchester Estates". W. A. Ellis Estate Agents. 2012. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- Mitford, Deborah (9 November 2010). Wait for Me!: Memoirs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374207687.

Further reading

edit- Giles Fox-Strangways, 6th Earl of Ilchester:

- The House of the Hollands 1605–1820, London, 1937

- Chronicles of Holland House, 1820–1900, London, 1937

- Catalogue of pictures belonging to the Earl of Ilchester at Holland House, London, 1904

External links

edit- Media

- Archive film from Pathé News showing the ruins of Holland House after its destruction in the Blitz.

- Photos from 1952, when the house was sold to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, showing the damaged interior of the house, and workers clearing rubble.

- Photographic gallery of the current appearance of the building

- Websites