This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

In the Iron Age, Essex was home to the Trinovantes. In AD 43 the Roman conquest of Britain saw Roman control established over Essex, with the centre of Roman power in Britain being, for a time, Colchester. The Boudiccan revolt saw Colchester razed, but it was rebuilt.

Following the collapse of Roman authority, Essex was settled by Saxons, and in the 6th century the kingdom of the East Saxons, from which Essex gets its name, emerged. The early East Saxons were pagan, but were converted to Christianity by Cedd, who is now the county's patron saint, in 653. Essex was frequently under the overlordship of other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and by the late 9th century had been absorbed by the kingdom of Wessex. In the mid 9th century Essex was conquered by Scandinavian invaders, and became part of the Danelaw, before being reconquered by Wessex in the early 10th century, and becoming part of the emergent kingdom of England. Colchester and Maldon established themselves as Essex's principal towns by the end of this period.

Essex has been part of England ever since, and has played a role in events such as the Peasant's Revolt of 1381, the Wars of the Roses and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Throughout the medieval era, Essex was one of the most densely-populated and prosperous parts of England, in no small part thanks to the wool trade in which it was heavily involved. Chelmsford established itself as the county town, while Harwich emerged as a major port and naval base. Overseas, Essex people made major contributions to the colonisation of the Americas.

In the industrial era, the introduction of the railway saw the rise of several seaside resort towns throughout Essex, most notably Southend-on-Sea and Clacton-on-Sea. Meanwhile, the expansion of London saw parts of south-west Essex subsumed by Greater London, which would only become official with the London Government Act 1963.

The Second World War saw much military activity in Essex, with fighter airbases in the south of the country taking part in the Battle of Britain, and bomber airbases in the north contributing to the bombing of Germany. After the war, new towns were established at Basildon and Harlow, and Essex's economy increasingly became dependant on the London commute. The decline of seaside resorts across Britain hit Essex particularly hard, impoverishing areas such as Jaywick.

Iron Age

editIn the Iron Age, Essex and parts of southern Suffolk were controlled by the local Trinovantes tribe. Their production of their own coinage marks them out as one of the more advanced tribes on the island, this advantage (in common with other tribes in the south-east) is probably due to the Belgic element within their elite. Their capital was the oppidum (a type of town) of Camulodunon (present-day Colchester), which had its own mint. The tribe were in extended conflict with their western neighbours, the Catuvellauni, and steadily lost ground. By AD 10 they had come under the complete control of the Catuvellauni, who took Colchester as their own capital.[1]

Reigning from Camulodunon, Cunobelin was the most powerful of the Iron Age kings in Briton, and indeed was sometimes described in Roman sources as 'king of the Britons.' While open to Roman influence, Cunobelin seems to have retained a significant degree of independence.[2]

Roman period

editCunobelin's death in c. 40-43 provoked a succession crisis, in which his son Caractacus initially came out on top. The disputed succession, and the exile of Cunobelin's son Arminius, provided the Roman emperor Claudius with a pretext to invade Britain. The Roman invasion began in 43, with four legions supported by auxiliaries landing unopposed in Kent. From there, the Romans advanced towards the Thames, defeating the British at an unknown river-crossing, and again on the banks of the Thames. At the Thames, the Romans paused and awaited the arrival of Claudius, who personally lead the advance on, and capture of, Camulodunon.[3]

Claudius held a review of his invasion force on Lexden Heath where the army formally proclaimed him Imperator. The invasion force that assembled before him included four legions, mounted auxiliaries and an elephant corps – a force of around 30,000 men.[4] At Camulodunon, the kings of eleven British tribes surrendered to Claudius, though not Caractacus, who would later lead the resistance against Roman rule in western Britain.[3][5]

A legionary fortress was built in Camulodunon in c. 43, to be followed in c. 49 by the establishment of a veteran colony there, known formally as 'Colonia Claudia Victricensis,' but more often as Camulodunum.[6] It was initially the capital and most important city in Roman Britain, and in it was constructed a temple to the God-Emperor Claudius - the largest building of its kind in Roman Britain.[7][8]

The establishment of the Colonia is thought to have involved extensive appropriation of land from local people. This, and other grievances, led to the Trinovantes joining their northern neighbours, the Iceni, in the Boudiccan revolt.[9] The rebels entered the city, and after a Roman last stand at the temple of Claudius, razed it, massacring many thousands. A Roman force attempting to relieve Colchester was destroyed in pitched battle.[10] The rebels then proceeded to sack Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St Albans), before being defeated in battle. Contemporary sources claim revolt may have killed as many as 80,000 people. The Romans are likely to have ravaged the lands of the rebel tribes, so Essex will have suffered greatly.[11]

Camulodunum was rebuilt after the revolt, though it is unclear if it was ever again capital, or if that role had passed to Londinium; Tacitus is ambiguous on the subject in c. 60. The city was home to the only Roman circus for chariot racing in Britain, a theatre opposite the Temple of Claudius, and historians have speculated an amphitheatre may also have been built there.[12]

Throughout this, the Trinovantes' identity persisted. Roman provinces were divided into civitas for local government purposes – with a civitas for the Trinovantes strongly implied by Ptolemy.[13] Christianity is thought to have been flourishing among the Trinovantes in the fourth century, indications include the remains of a probable church at Colchester,[14] the church dates from sometime after 320, shortly after the Constantine the Great granted freedom of worship to Christians in 313. Other archaeological evidence include a chi-rho symbol etched on a tile at a site in Wickford, and a gold ring inscribed with a chi-rho monogram found at Brentwood. [15]

The late Roman period, and the period shortly after, was the setting for the King Cole legends based around Colchester.[16] One version of the legend concerns St Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great. The legend makes her the daughter of Coel, Duke of the Britons (King Cole) and in it she gives birth to Constantine in Colchester. This, and related legends, are at variance with biographical details as they are now known, but it is likely that Constantine, and his father, Constantius spent time in Colchester during their years in Britain.[17] The presence of St Helena in the country is less certain.

From the early third century, Britain was increasingly subject to Saxon raids against coastal areas, including Essex. To protect against this threat, a series of forts were built along the coast, known as the Saxon Shore; one such fort was built in the late third century at Othona (present Bradwell-on-Sea).[18]

Roman authority in Britain entered a steep decline in the middle of the fourth century, culminating in the province's rejection of Constantine III in 409, following his withdrawal of troops from the province in 407. Outside of the Empire, the governing apparatus of Britain rapidly collapsed, ushering in a period of relative anarchy.[19] Urban sites including Camulodunum were mostly abandoned, though there is some evidence of Saxon settlers among the ruins from early in the 5th century.[20]

Medieval period

editAnglo-Saxon Essex

editMain article: Kingdom of Essex

The first Saxons to settle in Essex were likely mercenaries, contracted by the Romano-British to garrison the Saxon Shore fortifications that protected the east coast against sea-borne raiders. Late Roman military belt sets, dating to the early 5th century, have been discovered in Essex, concentrated in coastal areas, including those with known military associations such as Colchester and Othona.[21]

This accords with the earliest written account of post-Roman Britain, that of Gildas, which suggests the Anglo-Saxons first came to Britain as mercenaries, before turning on the Roman-British, and claiming much of the country for their own.[22] The next written account comes from Bede in c. 731. Bede describes three principal groups - the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes - colonising England. The Saxon area he divides into the East, South (Sussex), and West Saxons (Wessex).[23] It is from the Old English term for East Saxons, Ēastseaxe, that the name Essex derives. Archaeological evidence - primarily grave goods and burial practices - shows Essex as a region influenced both by 'Saxon' and 'Anglian' material culture, rather than conforming strongly to a Saxon identity.[24]

The exact process by which Germanic, Anglo-Saxon identity, culture, and language became so widespread in England remains a subject of intense scholarly debate. The traditional view has been that there was large-scale migration from continental Europe to England. This is, however, contradicted by genetic evidence that suggests migration took place on a much smaller scale. Recent scholarship proposes lower levels and migration, alongside a cultural shift whereby Romano-British communities adopted the culture of an Anglo-Saxon elite, in order to gain "status, security, social opportunity and access to wealth."[25]

The kingdom of the East Saxons begins to emerge in the 6th century. It is at this time that elite burials first appear in Essex's archaeological record, most of which feature Kentish styles of dress and jewellery.[26] Some sources give the first king of the East Saxons as Æescwine (or Erkenwine) in 527, whose name suggests a connection with Kent. More widely attested as first king, however, is Sledd in 587. Again a Kentish connection is visible, as Sledd's wife Ricula was the sister of the Kentish king Æthelberht.[27] The early kings of the East Saxons were pagan and uniquely amongst the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms traced their lineage back to Seaxnēat, god of the Saxons, in addition to Woden. The kings of Essex are notable for their S-nomenclature, nearly all of them begin with the letter S.[28]

The East Saxon kingdom extended beyond the boundaries of present-day Essex, into Middlesex and parts of eastern Hertfordshire. Middlesex, at least, was likely viewed as a separate province to Essex proper, and may at times have been provided its 'own' king from the East Saxon royal family. It is also possible that the East Saxon kingdom may once have encompassed Surrey, whose name derives from 'Southern District', though there is limited evidence for this.[29]

While Christianity had been introduced to Essex in Roman times, by the late 6th century, the East Saxons and their kings were pagans. The Gregorian mission arrived in neighbouring Kent in 597 to begin the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. The first sign of Christianity among the East Saxons is the presence of Christian grave goods at the Prittlewell royal burial, dated to around 600. In 604, the Gregorian mission reached Essex. King Sæbert was baptised, a Bishop of London (Mellitus) was consecrated, and St Paul's Cathedral was founded in London. The Christianisation of the kings of Essex was short-lived, however, as on Sæbert's death in 616 his sons renounced Christianity and drove out Mellitus.[30][31]

The kingdom re-converted around 653, after St Cedd, a monk from Lindisfarne and now the patron saint of Essex, converted Sigeberht II around 653, and was appointed Bishop of the East Saxons; which appears to have been a separate position from Bishop of London.[30] Around this time the Chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall was built in Bradwell-on-Sea, which ranks among the oldest English churches still in use today.[32][33] The last pagan king of Essex was Sighere, an apostate who was joint-king alongside his Christian cousin Sæbbi; Sæbbi outlived his cousin, and Christianity fully took hold in Essex.[34]

During Sæbbi's reign, the East Saxon kingdom conquered Kent and brought it under their overlordship, with Sæbbi's son Swæfheard ruling the province as king, but subordinate to his father in Essex. This influence, however, seems to have come to an end by 694.[28] From this point onwards, Essex fell increasingly under the overlordship of foreign kings, primarily of Mercia, with Coenwulf reducing the kings of Essex to ealdorman status. Furthermore, the Mercian kings separated Essex's territories in Hertfordshire and Middlesex from the core territory of Essex.[29] In AD 824, Ecgberht, the King of the Wessex and grandfather of Alfred the Great, defeated the Mercians at the Battle of Ellandun in Wiltshire, fundamentally changing the balance of power in southern England. The small kingdoms of Essex, Sussex, Surrey and Kent were subsequently absorbed into Wessex.[35] From this time onwards, Essex was often ruled - along with the other smaller kingdoms of eastern England - by a son of the king of Wessex.[36]

The coming of the Great Heathen Army in 865 saw Essex among the English counties which were conquered by the pagan Norse king Guthrum, and became part of the Danelaw. Following Alfred the Great's victory at the Battle of Edington in 878, Guthrum converted to Christianity, and a border was drawn between his realm and Alfred's along the River Lea.[37] The extent of Scandinavian control in Essex is disputed, with linguistic and archaeological evidence of such limited to the north-east of the county.[38]

In 894 Alfred's son Edward campaigned into Essex and defeated a Viking army at the Battle of Benfleet, but did not advance further.[39] He returned as king of Wessex in 917, and brought the country back under Wessex's control; his son Æthelstan was to become the first king of the English.[40] The later Anglo-Saxon period shows two further major battles fought with the Norse in Essex; the Battle of Maldon in 991,[41] and the Battle of Assandun (probably at either Ashingdon or Ashdon) in 1016.[42]

By the end of the Anglo-Saxon period, the county was divided into the Hundreds of Essex, which would persist with little alteration for a millennium. This time period also saw Colchester and Maldon establish themselves as the principal towns of Essex, with Colchester the larger of the two.[43]

Post-Norman Conquest

editHaving conquered England, William the Conqueror initially based himself at Barking Abbey, an already ancient nunnery, for several months while a secure base, which eventually became the Tower of London could be established in the city. While at Barking William received the submission of some of England's leading nobles. The invaders established a number of castles in the county, to help protect the new elites in a hostile country. There were castles at Colchester, Castle Hedingham, Rayleigh, Pleshey and elsewhere. Hadleigh Castle was developed much later, in the thirteenth century.

With the Norman conquest came the introduction of the manorial system, by which Norman-style 'manors' replaced the Anglo-Saxon hide as the chief method by which landholding was organised. A number of William's supporters were rewarded with extensive estates throughout Essex, including Aubrey de Vere, who had Hedingham Castle built, and Geoffrey de Mandeville, whose grandson would become the first Earl of Essex.[44][45] After the arrival of the Normans, the Forest of Essex was established as a royal forest, however, at that time, the term[46] was a legal term. There was a weak correlation between the area covered by the Forest of Essex (the large majority of the county) and the much smaller area covered by woodland. An analysis of Domesday returns for Essex has shown that the Forest of Essex was mostly farmland, and that the county as a whole was 20% wooded in 1086.[47]

Chelmsford began growing into a major market town following the Norman conquest, with a bridge over the River Can built by Maurice, Bishop of London in c. 1100, and the town's royal charter granted in 1199.[48]

After that point population growth caused the proportion of woodland to fall steadily until the arrival of the Black Death, in 1348, killed between a third and a half of England's population, leading to a long term stabilisation of the extent of woodland. Similarly, various pressures led to areas being removed from the legal Forest of Essex and it ceased to exist as a legal entity after 1327,[49] and after that time Forest Law applied to smaller areas: the forests of Writtle (near Chelmsford), long lost Kingswood (near Colchester),[47] Hatfield, and Waltham Forest.

Waltham Forest had covered parts of the Hundreds of Waltham, Becontree and Ongar. It also included the physical woodland areas subsequently legally afforested (designated as a legal forest) and known as Epping Forest and Hainault Forest).[50]

Peasants Revolt, 1381

editThe Black Death significantly reduced England's population, leading to a change in the balance of power between the working population on one hand, and their masters and employers on the other. Over a period of several decades, national government brought in legislation to reverse the situation, but it was only partially successful and led to simmering resentment.

By 1381, England's economic situation was very poor due to the war with France, so a new Poll Tax was levied with commissioners being sent round the country to interrogate local officials in an attempt to ensure tax evasion was reduced and more money extracted. This was hugely unpopular and the Peasants' Revolt broke out in Brentwood on 1 June 1381. The revolt was partly inspired by the egalitarian preaching of the radical Essex priest John Ball.

Several thousand Essex rebels gathered at Bocking on 4 June, and then divided. Some heading to Suffolk to raise rebellion there, with the rest heading to London, some directly – via Bow Bridge and others may have gone via Kent. A large force of Kentish rebels under Wat Tyler, who may himself have been from Essex, also advanced on London while revolt also spread to a number of other parts of the country.

The rebels gained access to the walled City of London and gained control of the Tower of London. They carried out extensive looting in the capital and executed a number of their enemies, but the revolt began to dissipate after the events at West Smithfield on 15 June, when the Mayor of London, William Walworth, killed the rebel leader Wat Tyler. The rebels prepared to fire arrows at the royal party but the 15 year old King Richard II rode toward the crowd and spoke to them, defusing the situation, in part by making a series of promises he did not subsequently keep.[51]

Having bought himself time, Richard was able to receive reinforcements and then crush the rebellion in Essex and elsewhere. His forces defeated rebels in battle at Billericay on 28 June, and there were mass executions including hangings and disembowellings at Chelmsford and Colchester.[52]

Wars of the Roses

editIn 1471, during the Wars of the Roses a force of around 2,000 Essex supporters of the Lancastrian cause crossed Bow Bridge to join with 3,000 Kentish Lancastrian supporters under the Bastard of Fauconberg.

The Essex men joined with their allies in attempting to storm Aldgate and Bishopsgate during an assault known as the Siege of London. The Lancastrians were defeated, and the Essex contingent retreated back over the Lea with heavy losses.[53]

Early modern period

editSpanish Armada

editIn 1588 Tilbury Fort was chosen as the focal point of the English defences against King Philip II's Spanish Armada, and the large veteran army he had ordered to invade England. The English believed that the Spanish would land near the Fort,[54] so Queen Elizabeth's small and relatively poorly trained forces gathered at Tilbury, where the Queen made her famous speech to the troops.

I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

In the event, the Spanish fleet was defeated at sea and scattered, and so no stand at Tilbury was required.

Colonisation of the Americas

editPeople from Essex were heavily involved in the colonisation of the Americas. The Mayflower, which carried the first settlers to New England, was a Harwich ship. Five of America's presidents (George Washington, John Adams, John Quincy Adams, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush) can trace their ancestry to Essex.[55]

Civil War

editEssex, London and the eastern counties backed Parliament in the English Civil War, but by 1648, this loyalty was stretched. In June 1648 a force of 500 Kentish Royalists landed near the Isle of Dogs, linked up with a small Royalist cavalry force from Essex, fought a battle with local parliamentarians at Bow Bridge, then crossed the River Lea into Essex.

The combined force, bolstered by extra forces, marched towards Royalist held Colchester, but a Parliamentarian force caught up with them just as they were about to enter the city's medieval walls, and a bitter battle was fought but the Royalists were able to retire to the security of the walls. The Siege of Colchester followed, but ten weeks' starvation and news of Royalist defeats elsewhere led the Royalists to surrender.[56]

Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Arthur Capell - who as a child had been a hostage during the Siege of Colchester - was named Earl of Essex, a title his descendants hold to this day.

Victorian era

editMuch of the development of the county was caused by the railway. By 1843 the Eastern Counties Railway had connected Bishopsgate station in London with Brentwood and Colchester. In 1856, they opened a branch to Loughton (later extended to Ongar) and by 1884 the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway had connected Fenchurch Street railway station in the City of London to Grays, Tilbury, Southend-on-Sea and Shoeburyness. Some of the railways were built primarily to transport goods but some (e.g. the Loughton branch) were to cater for commuter traffic; they unintentionally created the holiday resorts of Southend, Clacton and Frinton-on-Sea[citation needed].

County councils were created in England in 1889. Essex County Council was based in Chelmsford, although it met in London until 1938. Its control did not cover the entire county. The London suburb of West Ham and later East Ham and the resort of Southend-on-Sea became county boroughs independent of county council control.

Districts in 1894

edit| Municipal boroughs | Chelmsford, Colchester, Maldon, Saffron Walden, Southend-on-Sea |

|---|---|

| Urban districts | Barking Town, Braintree, Buckhurst Hill, Chingford, Clacton, East Ham, Grays, Halstead, Ilford, Leyton / Leytonstone, Romford, Shoeburyness, Waltham Holy Cross, Walthamstow, Walton on the Naze, Wanstead, Witham, Woodford |

| Rural districts | Belchamp, Billericay, Braintree, Bumpstead, Chelmsford, Dunmow, Epping, Halstead, Lexden and Winstree, Maldon, Ongar, Orsett, Rochford, Romford, Saffron Walden, Stanstead, Tendring |

Twentieth Century

editFirst World War

editThe Harwich Force - based, as the name suggests, in Harwich - played an important role in the North Sea theatre of the First World War.[57] On land, the Essex Regiment fought on the Western Front, including at the Battle of the Somme;[58] at Gallipoli; and in the Senussi and Sinai and Palestine campaigns.[59]

Second World War

editDuring the Second World War, Essex played a key role in the Battle of Britain, playing host to a number of RAF Fighter Command airfields in 11 Group, most notably three sector airfields at Hornchurch, North Weald, and Debden.[60] Later in the war a series of new airfields were built across northern Essex, for use by RAF Bomber Command and the United States Army Air Forces in the Combined Bomber Offensive against German-occupied Europe. Important wartime producers included Marconi electrical systems and Hoffman ballbearings in Chelmsford, and Paxman engines in Colchester, while Southend Pier served as a mustering point for convoys.

Post-war

editMuch of Essex is protected from development near to its boundary with Greater London and forms part of the Metropolitan Green Belt. In 1949 the new towns of Harlow and Basildon were created. These developments were intended to address the chronic housing shortage in London but were not intended to become dormitory towns, rather it was hoped the towns would form an economy independent of the capital. The railway station at Basildon, with a direct connection to the City, was not opened until 1974 after pressure from residents.

The proximity of London and its economic magnetism has caused many places in Essex to become desirable places for workers in the City of London to live. As London grew in the east places such as Barking and Romford were given greater autonomy and created as municipal boroughs.

Finally in 1965 under the London Government Act 1963 the County Borough of West Ham and the County Borough of East Ham were abolished and their area transferred to Greater London to form the London Borough of Newham.

Also at this time the Municipal Borough of Ilford and the Municipal Borough of Wanstead and Woodford were abolished and their area, plus part of the area of Chigwell Urban District (but not including Chigwell itself), were transferred to Greater London to form the London Borough of Redbridge. The Municipal Borough of Romford and Hornchurch Urban District were abolished and their area transferred to Greater London to form the London Borough of Havering.

The Municipal Borough of Leyton, the Municipal Borough of Chingford and the Municipal Borough of Walthamstow were abolished and their area transferred to Greater London to form the London Borough of Waltham Forest. The Municipal Borough of Barking and the Municipal Borough of Dagenham were abolished and their area transferred to Greater London to form the London Borough of Barking, renamed London Borough of Barking and Dagenham on 1 January 1980.

The 1990s

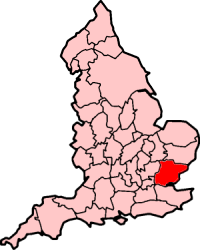

editEssex became part of the East of England Government Office Region in 1994 and was statistically counted as part of that region from 1999, having previously been part of the South East England region.

In 1998 the boroughs of Thurrock and Southend-on-Sea were given unitary authority status and ceased to be under county council control. They remain part of the ceremonial county.

Historical buildings

editThe importance of the Anglo-Saxon culture in Essex was only emphasized by the rich burial discovered at Prittlewell in 2003,[61] but the important Anglo-Saxon remains in Essex are mostly churches. St. Peter's straddles the wall of a Roman seafort at Bradwell (Othona), and is one of the early Anglo-Saxon, "Kentish" series of churches made famous by its documentation by Bede. Later Anglo-Saxon work may be seen in an important church tower at Holy Trinity, Colchester, an intact church at Hadstock, and elsewhere. At Greensted the walls of the nave are made of halved logs; although still the oldest church timber known in England, it is now thought to be early Norman.

-

The Chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall, founded by St Cedd in c.660

-

St. Mary's Church, Chickney, dating back to the late 10th century

-

Church of the Holy Trinity, c.1020, an Anglo-Saxon church in Colchester

-

Greensted Church, c.845, possibly the oldest wooden church in the world

Being a relatively stone-less County, it is unsurprising that some of the earliest examples of the mediaeval revival of brick-making can be found in Essex; Layer Marney Tower, Ingatestone Hall, and numerous parish churches exhibit the brickmakers' and bricklayers' skills in Essex. A two-volume typology of bricks, based entirely on Essex examples, has been published. Similarly, spectacular early-mediaeval timber construction is to be found in Essex, with perhaps the two Templars' barns at Cressing Temple being pre-eminent in the whole of England. There is a complete tree-ring dating series for Essex timber, much due to the work of Dr. Tyers at the University of Sheffield.

Mediaeval "gothic" architecture in timber, brick, rubble, and stone is to be found all over Essex. These range from the large churches at Chelmsford, Saffron Walden and Thaxted, to the little gem at Tilty. The ruined abbeys, however, such as the two in Colchester and that at Barking, are disappointing in comparison to those that can be found in other counties[citation needed]; Waltham is the exception[citation needed].

While the truncated remnant of Waltham Abbey was considered as a potential cathedral, elevation of the large parish church at Chelmsford was eventually preferred because of its location at the centre of the new diocese of Essex c.1908. Waltham Abbey remains the County's most impressive piece of mediaeval architecture.

-

Waltham Abbey Church, a 12th century structure

-

Chelmsford Cathedral, seat of the Bishop of Chelmsford

-

St Mary's in Saffron Walden, England's largest non-cathedral church

-

Thaxted Parish Church, c. 1340, nicknamed 'the Cathedral of Essex'

Quite apart from important towns like Colchester or Chelmsford, many smaller places in Essex exhibit continuity from ancient times. Perhaps the most amusing is the Anglo-Saxon church at Rivenhall, just north of Witham. A nearby, ruined Roman villa probably served as a source for its building materials, and the age of this church was underestimated by Pevsner by about a thousand years.

The villages of Wanstead and Woodford saw the French family setting up a brick making works adjacent to the road from Chelmsford to London, now known as Chigwell Road. This industry closed in 1952.

-

Colchester Castle, the largest Norman keep in Europe

-

Hedingham Castle, a well-preserved Norman keep

-

The ruins of Hadleigh Castle, built in the 13th century

-

Tilbury Fort, a Tudor-era artillery fortification

References

edit- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. passim. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- ^ Mattingly, David (2006). An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, 54 BC - AD 409. Penguin. pp. 72–75. ISBN 9780140148220.

- ^ a b Mattingly, David (2006), p. 92-99

- ^ Described in 'The Essex Landscape', by John Hunter, Essex Record Office, 1999. Chapter 4

- ^ Life in Roman Britain, Anthony Birley, 1964

- ^ Mattingly, David (2006), p. 269-271

- ^ Crummy, Philip (1997) City of Victory; the story of Colchester – Britain's first Roman town. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1 897719 04 3)

- ^ Wilson, Roger J.A. (2002) A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain (Fourth Edition). Published by Constable. (ISBN 1-84119-318-6)

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 48. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- ^ "Cornelius Tacitus, The Annals, BOOK XIV, chapter 32". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 51. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- ^ Mattingly, David (2006), p. 278-285

- ^ Rippon, Stephen (2018) [2018]. Kingdom, Civitas, and County. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-875937-9.

- ^ Details on the church, Colchester Archaeologist website https://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=34126 Archived 11 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 58. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6. the reference relates to the flourishing nature of Christiantity in fourth century Essex and the finds at Wickford and Brentwood

- ^ Gray, Adrian (1987) [1987]. Tales of Old Essex. Berkshire: Countryside Books. p. 27. ISBN 0-905392-98-1.

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 51. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6. The source states that the earliest record in the 14th century Colchester Oath Book, but recounted by Daniel Defoe and others

- ^ Mattingly, David (2006), p. 240-241

- ^ Mattingly, David (2006), p. 529-527

- ^ Mattingly, David (2006), p. 532

- ^ Mirrington, Alexander (2013). Transformations of Identity and Society in Essex, c.AD 400-1066. pp. 102–104.

- ^ Higham, N. J.; Ryan, Martin J. (2013). The Anglo-Saxon world. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 57–62. ISBN 978-0-300-12534-4.

- ^ Higham and Ryan (2013), p.72-76

- ^ Mirrington, Alexander (2013), p. 270-283

- ^ Higham and Ryan (2013), p.108-111

- ^ Mirrington, Alexander (2013), p. 134-138

- ^ Mirrington, Alexander (2013), p. 19-20

- ^ a b Yorke, Barbara. “The Kingdom of the East Saxons.” Anglo-Saxon England, vol. 14, 1985, pp. 1–36. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44509858. Accessed 12 Nov. 2024.

- ^ a b Yorke, Barbara (1985)

- ^ a b Yorke, Barbara (2023). "Cedd, Bradwell and the conversion of Anglo-Saxon England". In Dale, Johanna (ed.). St Peter-On-The-Wall: Landscape and heritage on the Essex coast. UCL Press. pp. 110–129.

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021). The Anglo-Saxons - A History of the Beginnings of England: 400 – 1066. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781643135359.

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 95

- ^ "Bradwell on Sea St Peter on the Wall Church | National Churches Trust". National Churches Trust. Retrieved 12 November 2024.

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (2023)

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 179-180

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 188

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 219

- ^ Mirrington, Alexander (2013), p. 292-296

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 240

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 257

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 326-329

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 358

- ^ "Medieval Colchester: Introduction | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ "Aubrey de Vere | Domesday Book". opendomesday.org. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ "Geoffrey de Mandeville | Domesday Book". opendomesday.org. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ forest

- ^ a b Rackham, Oliver (1990) [1976]. Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. New York: Phoenix Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-8421-2469-7.

- ^ "Tindal Street Origins". www.chelmsford.gov.uk. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ The Essex Landscape, a study of its form and history. John Hunter, pub Essex Record Office 1999. ISBN 1-898529-15-9

- ^ Raymond Grant (1991). The royal forests of England. Wolfeboro Falls, NH: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-781-X. OL 1878197M. 086299781X. see table, p224 for Essex Stanestreet and p221-229 for details of each forest

- ^ The English: A Social History 1066-1945. p36-37 Christopher Hibbert, Paladin Publishing 1988, ISBN 0 586 08471 1

- ^ Commentary on the Battle of Billericay and the aftermath of the revolt in Essex: Whybra, Julian. "The Battle of Norsey Wood, 1381" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Overview of the events of 1471: Rickard, J (27 February 2014). "Siege of London, 12-15 May 1471". Military History Encyclopedia on the Web. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020.

- ^ Connatty, Mary (1987) [1987]. The National Trust Book of the Armada. London: Kingfisher Books. p. 25. ISBN 0-86272-282-9.

- ^ "American Connections - Visit Essex". Visit Essex. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Royle, Trevor (2006). Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660. Abacus. pp. 449–452. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- ^ Dunn, Steve (2022). The Harwich Striking Force: The Royal Navy's Front Line in the North Sea 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 9781399015974.

- ^ Baker, Chris. "The Essex Regiment". Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ John Wm. Burrows, Essex Units in the War 1914–1919, Vol 5, Essex Territorial Infantry Brigade (4th, 5th, 6th and 7th Battalions), Also 8th (Cyclist) Battalion The Essex Regiment, Southend: John H. Burrows & Sons, 1932.

- ^ Bungay, Stephen (2000). The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain. Aurum Press. p. 62. ISBN 9781854107213.

- ^ Morris, Marc (2021), p. 64

Further reading

edit- Pevsner (the "Buildings of England" series, Penguin) is the best general introduction to the County's architecture. In the new [when?]editions, 'London over the border' will now [when?] appear with London: East, instead of with the rest of the County, as formerly.

Hidden Heritage – Discovering Ancient Essex, by Terry Johnson by Terry Johnson Whilst major sites such as Stonehenge and Avebury are well known, few people realise how rich in ancient sites are other areas of Britain. Terry first examines features of the landscape and unusual church carvings in general, then gives a detailed listing of interesting sites in Essex with associated legends and folklore, in addition to examining possible leys. ISBN 1898307 709