Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht (Lord, do not pass judgment on Your servant), BWV 105 is a church cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach. He composed it in Leipzig for the ninth Sunday after Trinity and first performed it on 25 July 1723. The musicologist Alfred Dürr has described the cantata as one of "the most sublime descriptions of the soul in baroque and Christian art".

| Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht | |

|---|---|

BWV 105 | |

| Church cantata by J. S. Bach | |

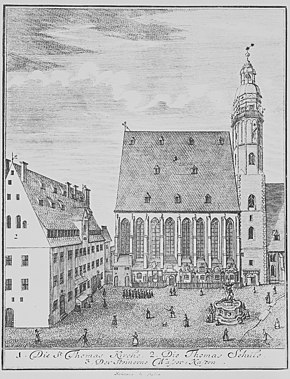

Engraving of the Thomaskirche in Leipzig in 1723. | |

| Occasion | 9th Sunday after Trinity |

| Chorale | "Jesu, der du meine Seele" by Johann Rist |

| Performed | 25 July 1723: Leipzig |

| Movements | 6 |

| Vocal | SATB soloists and choir |

| Instrumental |

|

History and text

editBach composed the cantata in 1723 in his first year in Leipzig for the Ninth Sunday after Trinity. It is likely that the anonymous librettist was a theologian from the city; the text begins with the second verse of Psalm 143, "And enter not into judgment with thy servant: for in thy sight shall no man living be justified" (Psalms 143:2).[1][2][3][4] The psalm is one of Martin Luther's Bußpsalmen, his German translations of the seven penitential psalms, first published in Wittenberg in early 1517, half a year before the Ninety-five theses. After being reprinted and even pirated all over Germany, there was a revised edition in 1525.[5][6][7]

The prescribed readings for the Sunday were from the First Epistle to the Corinthians, a warning of false gods and consolation in temptation (1 Corinthians 10:6–13), and from the Gospel of Luke, the parable of the Unjust Steward (Luke 16:1–9). The theme of the cantata is derived from the Gospel: since mankind cannot survive before God's judgement, he should forswear earthly pleasures, "the mammon of unrighteousness," for the friendship of Jesus alone; for by His death mankind's guilt was absolved, opening up "the everlasting habitations." That part of the libretto covers the fourth and fifth movements (the second recitatives and arias). The alto recitative draws from biblical allusions in Psalms 51:11—"Cast me not away from thy presence"— and Malachi 3:5—"I will come near to you to judgment; and I will be a swift witness against the sorcerers, and against the adulterers." The text of the soprano aria is borrowed from Romans 2:15—"while accusing or else excusing one another." There is a reference to Paul's epistles in the second recitative, Colossians 2:14—"Blotting out the handwriting of ordinances that was against us" and "nailing it to his cross." The closing chorale is the eleventh verse of the hymn Jesu, der du meine Seele, written by Johann Rist in 1641.[1]

Bach first performed the cantata, on 25 July 1723, at the Thomaskirche in Leipzig.[4][1][8]

Scoring and structure

editThe cantata in six movements is scored for four vocal soloists (soprano, alto, tenor and bass), a four-part choir, corno, two oboes, two violins, viola, and basso continuo.[1]

- Chorus: Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht (Lord, enter not into judgment with thy servant)

- Recitative (alto): Mein Gott, verwirf mich nicht (My God, cast me not away)

- Aria (soprano): Wie zittern und wanken der Sünder Gedanken (How they quiver and waver, the thoughts of sinners)

- Recitative (bass): Wohl aber dem, der seinen Bürgen weiß (Happy is he who knows his protector)

- Aria (tenor): Kann ich nur Jesum mir zum Freunde machen (If I can but make Jesus my friend)

- Chorale: Nun, ich weiß, du wirst mir stillen, mein Gewissen, das mich plagt (Now I know that Thou will calm my conscience that torments me.)

Musical description of movements

editThe cantata opens with a chorus in two parts, a form of prelude and fugue, corresponding to the first two phrases of Psalm 143, "Lord, enter not into judgment with thy servant / for in thy sight shall no man living be justified." As William G. Whittaker writes, "The chorus is so masterly that even a close analysis can only do scant justice to it."[2][9]

The orchestra is scored is for four voices, the two upper voices providing the first violins, oboe and corno colla parte and the others the second violins and oboe; in addition to violas there is a basso continuo. In the second violin parts of the opening movement, there are sections requiring notes below the normal range of the baroque oboe (B♭ and G below middle C): in that case either a different reed instrument can be used; or, as suggested in Leisinger (1999), the few notes outside the range of the baroque oboe can be transposed. It is also unclear what baroque instrument Bach had in mind for a corno—a corno da caccia, a corno da tirarsi or some other baroque woodwind instrument (such as a cornetto) that can double the soprano or alto voices. The choice of instrument likewise has to create the right balance between the first violins and tenor in the second aria.[2][4][10][11][12]

The monumental first part, marked adagio, starts in G minor with a sombre harmonically complex orchestral eight-bar ritornello. The throbbing repeated quaver beats of the figured bass play ceaselessly in the prelude. The ritornello has a penitent mood, its slow canon full of tortured chromatic modulations and suspended sevenths, which develop into sighing, mournful motifs in the violins and oboes. Similar chromaticism has been used elsewhere by Bach[13] to illustrate the crucifixion, for example for the Crucifixus section of the Credo in the Mass in B minor[14] and for the last stanza, "trug uns'rer Sünden schwere Bürd' wohl an dem Kreuze lange", in the choral prelude O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß, BWV 622.[15]

After the first ritornello, the instruments remain silent except for the pulsating basso continuo; the chorus sings in canon for six bars with new independent material in polyphonic motet style. First the alto starts singing a detached crotchet "Herr" followed by semiquavers motifs for "gehe nicht ins Gericht"; two beats later the tenor starts similarly, then the soprano and then the bass. The four voices continue singing the musical phrase "Herr, gehe nicht in Gericht" in an outpouring of imitative diminutions, until reaching a cadence on "mit deinem Knecht."[16] There is then a reprise of the solemn eight-bar ritornello, now in the dominant key with the upper parts interchanged. The six-bar chorus episode is repeated, with the alto responding to the soprano, and then the bass to the tenor. The chorus is now accompanied by the orchestra in double counterpoint, employing motifs derived from the first episode for chorus. After a cadence in the chorus, the orchestra briefly continues the double counterpoint, until there is a third freely composed episode for chorus. Now the sopranos lead the altos, and then the tenors lead the basses. The third episode lasts twelve bars and is richly scored, combining all the musical ideas from the chorus and orchestra: after less than three bars into the episode, in a moment of pathos, the original orchestral ritornello is played in counterpoint with the chorus for the first time. As Spitta writes, "at last it gives out its own penitential cry, going through it completely in the middle range of compass, as if it flowed straight from the hearts of singing hosts." The prelude concludes gracefully on a pedal point, with a coda similar to the brief orchestral interlude.[1][9][2][17]

The second part of the first movement is a spirited permutation fugue, marked allegro, initially scored for only the concertante singers and continuo, but eventually taken up by the whole ripieno choir, doubled by the orchestra. The tone of the text is condemnatory: "Denn vor dir wird kein Lebendiger gerecht"—"For in thy sight shall no man living be justified." The subject of the fugue theme commences resolutely with detached crotchets for "Denn", sung initially by the tenor accompanied by the basso continuo. The following fugal entry is sung by the bass, with the tenor now taking up the countersubject derived partly on the continuo quaver figures at the very beginning of the fugue. The lower voices are joined by successive fugal entries in the soprano and alto. After 21 bars of tightly scored choral singing, the tutti entries begin commencing with the basses doubling the continuo, followed by the tenors doubling the violas, the altos the second violins and oboe and the sopranos the first violins, oboe and corno. The extended fugue, with its increasingly fraught mood of denunciation, draws to a close after a further 50 bars. As André Pirro has commented, in the music for Bach's prelude, "neither the description, the drama nor the particular reference to words matter; instead it is the substance that has to be expressed, soberly, without gesticulation, but with a sense of authority, like a herald proclaiming a law or a philosopher declaring the principles of his system." Of the fugue, Pirro writes, "It is not simply a matter of bowing to the just judge, but of showing the inevitable severity of justice. [...] Not only does the repetitive motif of the fugue multiply the overwhelming sentence, but the infallible development of the composition predicts that the punishment will follow from the sin. Bach uses the logic of his art to reveal, amongst its horrors, the axioms of his religion."[1][3][4][18][19]

The short but expressive alto recitative is followed by one of Bach's most original and striking arias, depicting in musical terms the anxiety and restless desperation of the sinner.[1] Spitta writes that, "A secret terror, and at the same time a profound grief pervades the whole [aria]."[9] The movement has been described as "one of the most impressive arias ever composed by Bach."[4]

|

|

The aria starts with an extended ritornello played eloquently on the oboe. The fragmented phrases in the oboe, anguished and mournful, are accompanied only by repeated semiquavers in the tremolo violins and steady quavers in the violas: the absence of a basso continuo and the amassing sevenths increase the feeling of anxiety and hopelessness. The ritornello concludes with a continuous semiquaver passage of lamentation—musical material heard several times later on the oboe but never the voice. Taking up the detached motifs of the ritornello, the soprano starts the A section, singing the first couplet of the aria, "Wie zittern und wanken, Der Sũnder Gedanken," with the oboe following in canon one crotchet later: their duet is followed by a repetition of the semiquaver passage for oboe. The soprano and oboe repeat the music for the couplet, but at that point the soprano suddenly sings the second couplet, "Indem sie sich unter einander verklagen ... ," accompanied only by the violas, with completely new musical material. The continuous remarkable melodic line of the soprano, with its frenetic upward semiquaver and semidemiquaver runs, are developed in canon with the oboe, as if "each makes complaints about the other." Together the two soloists interweave two highly ornate but tortuous melodic lines, their melismas and disturbing dissonances representing the troubled soul. After a free reprise of the A section for soprano and oboe, there is shorter B section for the third couplet. More sustained then the A sections, it is derived from the musical material in the ritornello. The aria concludes with a reprise of the ritornello. The canonic voice leading, with the oboe echoing the soprano one crotchet later, is similar to the beginning of the sixth Brandenburg Concerto.[1][3][4][2]

The mood becomes hopeful in the following accompanied bass recitative: Jesus' assurance that the sinner will attain salvation through His death on the cross. The bass solo is accompanied by the violins and violas playing gentle semiquaver figures; and by the basso continuo playing repeated pizzicato quaver octaves. In Bach's musical iconography, these repeated quavers represent the death knell, when—in the record of goods, body and life—judgement on the soul is passed by God. The recitative leads to a strict da capo aria for tenor, corno and strings, which brings a new rhythmic energy, ecstatic and animated.

|

|

The ritornello introduction in the corno solo of the aria is initially doubled by the first violins, but then transformed to more rapid and filigree passagework in demisemiquavers. The tenor part has a remarkable dance-like quality, similar to a gavotte, which results in the off-the-beat division of phrases into a half-bar—Kann ich nur—or a bar—Jesum nur zum Freunde machen). The angular writing in the tenor part for the phrase So gilt der Mammon nichts bei mir is particularly spirited, with successive upward leaps for the word nichts. There is a contrasting mood in the middle section of the aria, when the corno does not play, "as if reluctant to reflect the comparison." In the middle section, although the melodic material for the tenor is independent, the string accompaniment is derived from the theme of the original ritornello as well as the garlands of demisemiquavers.[1][3][2][9]

As one of the editors for the Neue Bach-Gesellschaft, Robert L. Marshall was responsible for creating an urtext edition of the cantata for Bärenreiter in 1985. His preparation started in 1972, using the rare opportunity to have the autograph manuscript of Bach's full score available, created by Bach as a "composing score". Marshall attempted to reverse the process, analysing how Bach might have set about composing movements, altering portions if required. For the last chorale, where the strings accompany the chorus and other instruments colla parte, the two last pages of the autograph score reveal the many modifications Bach made.[20][21][22] Throughout the cantata, Bach's use of "word painting" is prevalent, but in the final chorale it is particularly imaginative.[3]

|

|

The sopranos and the altos play the chorale reinforces by the corno and oboes, while the accompanying tremolo string motif returns. With each successive stanza, the tremolo gradually becomes less rapid and dissonant—the repeated semiquavers change to triplets, then quavers, then tied triplets and finally steady crotchets for the brief coda. Musically the chorale echoes the calming of man after conciliation with his Maker, bringing to an end a cantata that the musicologist Alfred Dürr has described as one of "the most sublime descriptions of the soul in baroque and Christian art".[1][2]

Transcriptions

edit- Albrecht Mayer (oboe), The English Concert, Trinity Baroque, Concerto for Oboe and Strings (BWV 105/v, 170/i and 49/i), Decca, 2010.

Selected recordings

edit- Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht: Cantate pour le 9e dimanche après la Trinité, BWV 105, Berliner Motettenchor, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Fritz Lehmann, Gunthild Weber, Lore Fischer, Helmut Krebs, Hermann Schey, Archiv-Gallica 1952

- Les Grandes Cantates de J.S. Bach Vol. 16, Fritz Werner, Heinrich-Schütz-Chor Heilbronn, Pforzheim Chamber Orchestra, Agnes Giebel, Claudia Hellmann, Helmut Krebs, Erich Wenk, Erato 1963

- J. S. Bach Cantatas BWV 103, 104 and 105, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Tölzer Knabenchor, Concentus Musicus Wien, Wilhelm Wiedl, Paul Esswood, Kurt Equiluz, Ruud van der Meer, Teldec 1979

- J. S. Bach Cantata BWV 105, Helmuth Rilling, Bach-Collegium Stuttgart, Arleen Augér, Gabriele Schreckenbach / Helen Watts, Adalbert Kraus, Walter Heldwein, Hänssler 1978 / broadcast Alpirsbach Abbey 1983

- J. S. Bach Kantaten: BWV 73, 105 and 131, Philippe Herreweghe, Collegium Vocale, Barbara Schlick, Gérard Lesne, Howard Crook, Peter Kooy, Virgin Records 1990

- Leipzig Cantatas: BWV 25, 138, 105 and 46, Philippe Herreweghe, Collegium Vocale Gent, Hana Blažíková, Damien Guillon, Thomas Hobbs, Peter Kooij, PHI 2012

- J. S. Bach: Complete Cantatas Vol. 7, Ton Koopman, Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir, Lisa Larsson, Elisabeth von Magnus, Gerd Türk, Klaus Mertens, Antoine Marchand 1997

- J. S. Bach: The Sacred Cantatas, Vol. 10, Masaaki Suzuki, Bach Collegium Japan, Miah Persson, Robin Blaze, Makoto Sakurada, Peter Kooij, BIS

- J. S. Bach Cantatas: BWV 94, 105 and 168, John Eliot Gardiner, The English Baroque Soloists, The Monteverdi Choir, Katharine Fuge, Daniel Taylor, James Gilchrist, Peter Harvey, Archiv 2000

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dürr & Jones 2006, pp. 464–467

- ^ a b c d e f g Whittaker 1978, p. 630–637

- ^ a b c d e Anderson 1999, p. 215

- ^ a b c d e f Leisinger 1999

- ^ Lauer 1915

- ^ Bluhm 1948

- ^ Grossmann 1970

- ^ Green & Oertel 2019, p. 88

- ^ a b c d Spitta 1884, p. 424

- ^ Suzuki, Maasaki (1999). "Liner notes on instrumentation for BWV 105" (PDF).

- ^ Finscher, Ludwig (1979). "Remarks on the performance of BWV 105" (PDF).

- ^ Picon, Olivier. "The Corno da tirarsi" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-07-12. The appendix discusses the performance of BWV 105

- ^ Chafe 2003, p. 28 According to the iconography of the Lutheran canon, chromaticism symbolized Christus Coronobit Crucigeros

- ^ Butt 1991, p. 85

- ^ Williams 1980, pp. 61–62

- ^ In some period instrument performances, the first choral episode is only sung by the soloists; see Leisinger 1999.

- ^ For studying the cantata, there are a few "scrolling score" videos available on YouTube: one is labelled "Cantata nº 105 BWV 105"; another uses the autograph manuscript.

- ^ Cantagrel 2010

- ^ Pirro 1907

- ^ Marshall 1970

- ^ Marshall 1972

- ^ Marshall 1989

References

edit- Anderson, Nicholas (1999), "Herr, gehe nicht uns Gericht, BWV 105", in Boyd, Malcolm (ed.), J.S.Bach, Composer Companions, Oxford University Press, p. 223, ISBN 0198662084

- Bluhm, Heinz (1948), "Luther's View of Man in His First Published Work", The Harvard Theological Review, 41 (2), Cambridge University Press: 103–122, doi:10.1017/S0017816000019404, JSTOR 1508086

- Butt, John (1991), Bach: Mass in B minor, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38716-7

- Cantagrel, Gilles (2010), Les Canatates de J.-S. Bach (in French), Fayard, pp. 826–834, ISBN 9782213644349

- Chafe, Eric (2003), Analyzing Bach Cantatas, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-516182-3

- Dürr, Alfred; Jones, Richard D. P. (2006), The Cantatas of J.S. Bach, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-929776-2

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2014), Music in the Castle of Heaven: A Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach, Penguin Books, ISBN 9780141977591

- Green, Jonathan D.; Oertel, David W. (2019), Choral-Orchestral Repertoire: A Conductor's Guide, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 88, ISBN 9781442244672

- Grossmann, Maria (1970), "Wittenberg Printing, Early Sixteenth Century", Sixteenth Century Essays and Studies, 1, Sixteenth Century Journal: 53–74, doi:10.2307/3003685, JSTOR 3003685

- Lauer, Edward Henry (1915), "Luther's Translation of the Psalms in 1523-24", The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 14 (1), University of Illinois Press: 1–34, JSTOR 27700635

- Leisinger, Ulrich (1999), Foreword to J.S. Bach's Cantata, "Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht," BWV 105 (PDF), translated by David Kosviner, Carus Verlag

- Marshall, Robert L. (1970), "How J.S.Bach Composed Four-Part Chorales", The Musical Quarterly, 56 (2), Oxford University Press: 198–220, doi:10.1093/mq/LVI.2.198, JSTOR 740990. The compositional process of BWV 105/6 is described in detail based on Bach's changes to the autograph score.

- Marshall, Robert L. (1972), The Compositional Process of J.S. Bach: A Study of the Autograph Scores of the Vocal Works: Volume I, Princeton Legacy Library, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691200507

- Marshall, Robert L. (1989), "The Genesis of an Aria Ritornello: Observations on the Autograph Score of 'Wie zittern und wanken' BWV 105/3", The Music of Johann Sebastian Bach: the Sources, the Style, the Significance, Schirmer Books, pp. 143–160, ISBN 9780028717821

- Pirro, André (1907), L'Esthétique de Jean-Sébastien Bach (in French), Librairie Fischbacher

- Spitta, Philipp (1884), Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685-1750, translated by Clara Bell; J. A. Maitland-Fuller, Novello, Ewer & Co

- Whittaker, William Gillies (1978), The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach: sacred and secular, Volume I, Oxford University Press, pp. 630–635, ISBN 019315238X

- Williams, Peter (1980), The Organ Music of J.S. Bach, Vol. II, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-31700-2

- Wolff, Christoph (2020), Bach's Musical Universe: The Composer and His Work, W. W. Norton & Company

External links

edit- Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht, BWV 105: performance by the Netherlands Bach Society (video and background information)

- Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht, BWV 105: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht BWV 105; BC A 114 / Sacred cantata (9th Sunday after Trinity) Bach Digital

- Cantata BWV 105 Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht history, scoring, sources for text and music, translations to various languages, discography, discussion, bach-cantatas website

- BWV 105 – "Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht" English translation, Emmanuel Music

- BWV 105 Cantata notes, Emmanuel Music

- BWV 105 Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht English translation, University of Vermont

- Chapter 11 BWV 105 Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht / Lord, do not enter into judgement with Your servant. Julian Mincham, 2010