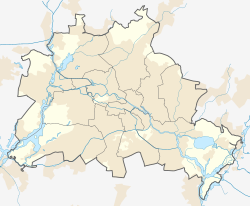

Hermannplatz, located in the northern part of the Berlin district of Neukölln, is a town square named on 9 September 1885. The name is similar to Hermannstraße and refers to Hermann the Cheruscan, although there is a belief that it was named after the Rixdorf community leader Hermann Boddin. Only Karstadt department store section belongs to the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district; the rest of the plaza is owned by Neukölln (property numbers 1–9). As Kreuzberg's most southeastern point, the square is still regarded as the gateway to Neukölln.[1][2]

Hermannplatz | |

|---|---|

Place in Berlin | |

Karstadt department store,

Hermannplatz to the right (view from Hermannstrasse ) | |

| Coordinates: 52°29′14″N 13°25′29″E / 52.4871°N 13.4248°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Berlin |

| Admin. region | Neukölln |

| Founded | 1885 |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

History and origin

editGeneral information

editHermannplatz is neither the nucleus nor the center of a settlement area, unlike many other urban squares. Instead, it is a segment of a road that became square-shaped between two road bends (later intersections). Thus, Hermannplatz was originally merely part of the route from Berlin to Mittenwalde via Rixdorf. The crossing path has led along the southern edge of the marshy Spree Valley at the foot of the Teltow Plateau since primeval times.[1]

Rollkrug

editIn August 1543, when Richardsdorf (later: Rixdorf) came under the ownership of the city Cölln, an inn already existed on the south side of the future Hermannplatz.[3] Around 1737, the Rollkrug Inn was built at the same location and derived its name from the rolling mountains that began in the south, an Ice Age ridge. In the middle of the 18th century, the square was also referred to as Platz am Rollkrug. For a long time, the Rollkrug Inn was the only building on the plaza, and it almost seemed like a foreign body until the Gründerzeit, when a metropolitan atmosphere emerged within a few decades.[4]

Towards the end of the 19th century, Rixdorf, a suburb of Berlin, had gained a reputation as an entertainment district, with its restaurants also having a questionable image. In 1885, the square at the Rollkrug was renamed Hermannplatz, and in 1907, the Rollkrug was demolished to make way for a commercial building. The commercial structure was also known as "Neuer Rollkrug," (New Rollkrug) and it still bears the inscription "Rollkrug" above the entrance on Hermannstraße. Since 1988, the building has been listed as a historical monument.[5][6]

Further development

editThe 1846 situation plan shows an additional inn called Zur guten Hoffnung next to the Rollkrug at Hermannplatz. It is located at the corner of Hermannplatz and Sonnenallee.[3] Although the building is no longer an inn, it is still depicted in the 1862 development plan for the surroundings of Berlin. On the opposite side of the street (at the corner of Hermannplatz and Urbanstraße), there is a restaurant called Gasthof zum Spreewald. Additionally, there is a pharmacy located at the corner of Hermannplatz and Hasenheide.

Before 1874, all imports into Berlin were subject to customs duty and had to be paid at the Accisehaus across from the Rollkrug. Although the building was still standing at the beginning of the 20th century, it had to be removed to make way for the widening of Hermannstraße and the construction of the new subway at Hermannplatz.[4]

The front building of Hermannstraße 4 was demolished to make room for a transformer station, which provided a temporary fix to the subway's power supply. In 1927/1928, the Hermannstraße transformer plant was constructed at Hermannstraße 5-8 according to Alfred Grenander's plans. It was designed to fit the new street layout and has been recognized as an architectural monument since the late 20th century. The plant converted the AC voltage received from the Kottbusser Ufer substation at 6000 volts and 50 hertz into DC voltage at 780 volts. The new street arrangement at the corner building to Hasenheide and the adjacent property Hermannstraße 4 is still evident from Hermannstraße since one can easily view the building's garden or the corner building's firewall.[5][3]

Tenement buildings were built on both sides of the square around 1860. However, in the mid-1920s, the residential buildings on the west side of the square were demolished again to make way for the construction of the subway and a retail store. During the reconstruction of the west side of the square, it was also broadened by 20 meters, giving it its present dimensions.

World War II

editBattle for Berlin

editOn 16 April 1945 the Red Army launched its attack across the Oder River. The 1st Belorussian Front of Soviet Marshal Zhukov aimed at the eastern parts of the city from Küstrin. The date is considered the beginning of the Battle of Berlin.

Bombardment of Hermannplatz

editOn 21 April 1945 Hermannplatz was among the first sites in Berlin to be attacked by the Soviets. The 1st Guards Tank Army, whose soldiers marched into Neukölln from the southeast, was the source of the artillery whose shells unexpectedly reached the square.[1]

A historian describes the situation:

"The sound was unlike anything Berliners had heard before - unlike the whistling of bombs whizzing down or the barking of flak. The people standing in front of the Karstadt department store on Hermannplatz raised their heads in amazement and listened. It was a low howl, somewhere in the distance, but then it turned into a hideous, shrill screech. For a moment, the people seemed hypnotized. Then they scattered. But it was too late. Artillery shells struck everywhere in the square, the first to reach the city. Mangled bodies banged against boarded-up storefronts. Men and women lay screaming in the street, writhing in pain. It was Saturday 21 April, at 11:30 a.m. sharp, and Berlin was a frontline city."

— Cornelius Ryan, Der letzte Kampf, pp. 261

The cannonade impacted the entire downtown area, with Soviet troops advancing slowly in the forefront near Köpenick, Karlshorst, and Buckow. The artillery fire disrupted defense deployment and forced people to move toward the city center.

On the morning of April 25, units of the 4th Guards Corps, supported by the 11th Guards Tank Corps, infiltrated Neukölln. The Soviet tanks march could be followed within the visibility. The defense at Hermannplatz was organized by SS Brigadeführer Gustav Krukenberg.[7]

Karstadt at Hermannplatz

editPhilipp Schaefer, the in-house architect of the Karstadt Group, designed the building, which was constructed between 1927 and 1929.[8] It stood 32 meters tall above Hermannplatz, with two towers of the same design rising an additional 24 meters above the building complex. Each of them was crowned by a light column that was 15 meters tall. The building itself was reminiscent of the high-rise architecture of the time in New York with its shell limestone façade and vertical articulation. With the light bands on the building and the light columns on the towers, the vertical structure was visible in the dark.[2]

At the time, Karstadt was considered to be the most advanced department store in Europe, featuring 24 escalators that connected its nine stories and 72,000 m2 of floor space, including two underground floors. Additionally, the building boasted eight freight elevators, 13 dumbwaiters, and 24 passenger elevators.[5] One of the freight elevators was able to transport fully loaded trucks directly to the food department on the fifth floor. Karstadt was also the first department store in Europe to offer direct subway access from the subway station, allowing passengers to travel directly to the basement of the building by taking the U7 or U8 line.[8]

"The building with the two blue light towers, which rose on the huge roof garden as an air signal for nearby Tempelhof, gave the cityscape a new sensory stimulus. To show how comfortable its stairways were, Karstadt had school rider Cilly Feindt ride her white horse up from the first floor to the roof garden."

— Walter Kiaulehn: Berlin. Schicksal einer Weltstadt, 1958, pp 34.

The city's most popular attraction, Karstadt am Hermannplatz, rose to prominence swiftly. The 4000 m2 roof garden, which has 500 seats and a wide variety of goods, was a particular favorite with the public, in addition to the abundance of items available. The bands played every afternoon and the view from 32 meters above Kreuzberg and Neukölln provided a unique ambiance.[8]

Destruction of the Karstadt building at the end of the Second World War

editAs the city's law and order deteriorated, a witness heard that the large department store Karstadt was being robbed. She immediately ran there, and people were taking whatever they could get. In the afternoon, the massive department store was blown up. The SS blew it up to prevent the 29 million marks worth of supplies they had stored in the cellars from falling into the hands of the Russians. There were several fatalities reported.[9]

On the evening of April 25, the doctor of a nearby military hospital for French prisoners of war witnessed the scene: "To the right, a cloud of smoke hid the two 80-meter-high towers of the Karstadt department store that towered over the neighborhood."[10]

Hermannplatz's defenses were effective until the following morning.[11] The Observer reported on April 26 that "the towers of the Karstadt department store were gone, and the big building was on fire."

Krukenberg "thought his men too bad to be 'burned out' on a comparatively unimportant section, so he managed to get his force moved from Neukölln to the city center."[12]

Reconstruction

editA small part of the department store on Hasenheide was saved and sales resumed by the end of July 1945. In 1950, reconstruction began. The architect Alfred Busse designed a four-story building that adjoined the preserved part of the building and was completed on the corner of Hasenheide and Hermannplatz by 1951.

Over the decades since its development, the edifice underwent several expansions. The most recent addition took place in 2000, along with a significant makeover of the exterior design. Helmut Kriegbaum, Jürgen Sawade, and Udo Landgraf were the architects hired for the extensions.

Reconstruction planning by Signa Holding

editSigna Holding, the owner of the Karstadt department store in Hermannplatz, revealed plans in January 2019 to erect an interpretive restoration of the façade damaged during WWII, including the distinctive towers. The renovation would also create additional space for offices, housing, restaurants, and retail.

Post-war era

editThe residential buildings on the east side of the square survived World War II, except for the building at the intersection with Sonnenallee. After the war, a one-story low-rise structure was built on Sonnenallee which was finally completed by the end of the 1990s. The height of this new structure was designed to match the eaves of the neighboring buildings and a hotel was subsequently established inside it.[13][14]

The transformation of the traffic facilities in Hermannplatz that took place in 1929 during the subway's construction, including rearranging streetcar stops and streets, continued until the mid-1980s. After the tram was shut down in the mid-1960s, the tracks in West Berlin’s square remained abandoned for years. However, during another redesign of the square in the early 1980s, the tracks were eventually removed. Finally, the newly renovated square was inaugurated with a folk festival on 27 April 1985.

Since then, it offers a vast pedestrian and market space, including the bronze sculpture Dancing Couple by Joachim Schmettau in the center. The couple, also known as the "Rixdorf Dancing Couple", used to spin twice an hour on their axis, but since the beginning of the 21st century, it has stood still. Joachim Schmettau, a founding member of the Aspects group of Berlin critical realists sculpted the bronze sculpture for the Federal Garden Show’s opening in the Britzer Garden. Hermannplatz, located in the same district, should also be beautified in this context. The sculpture stands on an approximately six-meter high partially hexagonal base, which is covered with yellow clinker bricks. The pedestal was repeatedly damaged by spray-painted graffiti, and there were also posters adhered to it. A hand-knitted patchwork dress that reaches a height of almost four meters was added to the pedestal in February 2022, making it extremely appealing. - It would be desirable if the district office of Neukölln had the rotating mechanism of the figures restarted.[13]

Future design

editIn 2006, the district office for Neukölln ordered a feasibility study for the redesign of Hermannplatz. The plan was to merge the two lanes on the northwest side to create a spacious plaza in front of the homes on the southeast side.[15] This would be transformed into a pedestrian area where only BVG buses would travel through at night for their stops, and during the day, cafes and bars could set up tables and chairs. The aim was to enhance the overall experience and minimize the possibility of accidents.[16] Plans also included redirecting bicycle traffic along street lanes instead of sidewalk lanes. The initial start date for the project was 2009, with the earliest possible start date being 2015.[15] However, the reconstruction could not begin as planned due to a lack of funding.[17] In 2014, the Senate announced the removal of the requirement to utilize the bike lane, but the timeline for additional measures remains uncertain.[18]

The square as a border

editHermannplatz has historically served as a dividing line between various districts. Initially, the square marked the boundary between Kreuzberg and Neukölln districts,[19] but later it also became the border between Berlin and Rixdorf. As a result of its expansion, the square's boundary was moved from its center to the western edge of the site. The second floor of the Karstadt building, which was built after World War II, juts out over the sidewalk. This leads to a peculiar situation where the department store, located entirely in Kreuzberg territory, protrudes into the airspace of Neukölln, and Karstadt must pay the district a fee for the "special use of public street space." In the late 1990s, this fee was 15,000 marks.

Adjacent streets

editHermannplatz appears as a large space between two junctions. The square is located at the intersection of Urbanstraße, Kottbusser Damm, and Sonnenallee in the north. Urbanstraße, which connects to the square from the west, was planned in 1874. Kottbusser Damm was originally known as Rixdorfer Damm until 1874 and is one of the oldest streets in the Kreuzberg neighborhood, with its name dating back to the sixteenth century. Sonnenallee, located east of Hermannplatz, dates back to 1890 and was originally named Kaiser-Friedrich-Straße in 1893. In 1938, the street east of Hermannplatz was named Braunauerstraße, after Hitler's birthplace. However, the name disappeared from the landscape in 1947 and was eventually changed to Sonnenallee. The intersection of Hasenheide, Hermannstraße, and Karl-Marx-Straße is located on the southern side of Hermannplatz. Hasenheidestraße was first constructed as a route in 1678, then in 1854, then expanded as a paved causeway. Hermannstraße has a very long history of being connected to Britz and was also known as merely Straße nach Britz until the end of the 19th century. In 1712, the postal route Berlin - Mittenwalde - Dresden was created along the current Hermannstraße route. One of the oldest streets in the square, along with Kottbusser Damm, is Karl Marx-Straße (Berliner Straße until 31 July 1947). A postal route to Cottbus led via Berliner Straße even before the Hermannstraße-based postal route to Dresden was established.

The increasing significance of Hermannplatz is documented by a traffic census from 1882. In one day, it counted 750 carts and 8,000 people (excluding the carters). About a century later, on 11 September 1986, a survey at the southern intersection (Karl-Marx-Strasse/Hermannstraße/Hasenheide) alone discovered 1,580 cyclists over 12 hours. There were no motor vehicle records.

Public transport

editBus and tram

editIn 1875, the Große Berliner Pferde-Eisenbahn (GBPfE) opened the Hallesches Tor-Rixdorf line which ran along Hasenhaide and Berliner Straße and passed tangent to Hermannplatz to the south.[20] In 1884 the Spittelmarkt - Rollkrug railway ran directly across Hermannplatz.[21] The line was then extended from Hermanstraße to Knesebeckstraße in 1885, at the cost of the Rixdorf municipality, which GBPfE acquired from the municipality in 1887. The Südliche Berliner Vorortbahn (Southern Berlin Suburban Railway) launched the first electric streetcar line into service via Hermannplatz on 1 July 1899.[22] The ring line went through Rixdorf, Britz, Tempelhof, Schöneberg, and Kreuzberg and was commonly referred to as the "Wüstenbahn" (desert line) because the southern section of the ring line passed through uninhabited territory.[23]

In 1905, there were plans to construct a suspension railroad that would run from Gesundbrunnen station via Hermannplatz to Rixdorf (Südring) station, which later became Neukölln (Südring) station. Unfortunately, the plan was never implemented.[22]

During the 1920s, Hermannplatz became a major bus route hub connecting various parts of the city. Multiple bus lines covered long distances, making it easier for people to travel across the city. One such example is the line A29, which began operating on 12 December 1921, with a length of 14.4 kilometers. It connected Pankow, Breite Straße to Hermannplatz.[21]

Before 1930, tram tracks existed on all the streets leading to Hermannplatz, and 15 different tram lines would stop there, including those running through the subway tunnels.[24] However, starting from the 1950s, the use of buses gradually increased in West Berlin, leading to the discontinuation of the final tram line (Line 27) passing through Hermannplatz on 1 October 1964. Line 95 continued to run tangent to Hermannplatz on the Urbanstraße-Sonnenallee axis as of 2 May 1965, but service was eventually terminated after the closure of the Britz depot in 1966. Since German unification, there have been attempts to extend the tram from the eastern part of Berlin (e.g. Warschauer Straße) to Hermannplatz.[25]

Subway

editIn the 1920s, Hermannplatz underwent significant transportation changes with the underground system's introduction on 11 April 1926. The Northern Southern Railway's first section, Hasenheide - Bergstraße (later renamed Südstern - Karl-Marx-Straße), was opened, connecting Seestraße in Wedding to Bergstraße in Neukölln. On 17 July 1927 Hermannplatz's second platform became operational, coinciding with the launch of the GN-Bahn (Gesundbrunnen-Neukölln) for the relatively short section from Boddin- to Schönleinstraße, which was later designated as the U8 line. The Hermannplatz subway station was designed as a tower station, featuring a vast hall nine meters below ground, with the platform for the later U7 line in the Hasenheide- Karl-Marx-Strasse street line, while the U8 platform in the Hermannplatz - Hermannstraße street line acted as a crossbar above. The ceilings of both platforms are at the same height, located directly under the street. The escalators between the two platforms were the first of their kind in the entire Berlin subway system, and the station's architects were Alfred Grenander and Alfred Fehse.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "HISTORY | Nicht ohne euch.Berlin". 2020-04-30. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ a b "Karstadt am Hermannplatz in Berlin by Philipp Schaefer". modernism-in-architecture.org. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ a b c "Rollkrug". www.berlin-hermannplatz.de. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ a b "Rollkrug in Kreuzberg". berlingeschichte.de. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ a b c "BERLIN Rollkrug-Lichtspiele". www.allekinos.com. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ "Neukölln". berlin.de. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ Erich Kuby. Die Russen in Berlin 1945. Scherz Verlag, München 1965. p. 146.

- ^ a b c "Letzte Hand am Kaufhaus". Berliner Tageblatt und Handelszeitung, 21. April 1929.

- ^ Cornelius Ryan. Der letzte Kampf. p. 282.

- ^ Tonny Le Tissier. Der Kampf um Berlin 1945. pp. 138 und 147.

- ^ Krukenberg, eher ein Truppenführer „alten Schlages“, war nicht für die Zerstörung des Karstadt-Hauses verantwortlich.

- ^ Erich Kuby. Die Russen in Berlin 1945. p. 148.

- ^ a b "Susanne Lenz: Ein Fall von Strickismus". Berliner Zeitung, 24. Februar 2022. p. 12.

- ^ "Berlin: The Fight For and Against a New Department Store at 'Hermannplatz'". The Berlin Spectator. 2020-05-30. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ a b "Zusammengefasste Projektbeispiele - FGS Berlin". www.fgsberlin.de. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Der Hermannplatz soll verschoben werden". Der Tagesspiegel, 3. Juni 2012.

- ^ "Grüne Xhain : Themen". 2015-05-18. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Jörn Hasselmann: Umbaupläne werden nicht umgesetzt". Der Tagesspiegel, 14. Oktober 2014.

- ^ "History of the Kreuzberg district in Berlin". www.citego.org. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ Eduard Buchmann. Die Entwickelung der Großen Berliner Straßenbahn und ihre Bedeutung für die Verkehrsentwickelung Berlins. Julius Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 1910. pp. 2–10.

- ^ a b Joseph Fischer-Dick. "Fünfundzwanzig Jahre bei der Grossen Berliner Pferdebahn". Zeitschrift für das gesamte Local- und Straßenbahnwesen. Wiesbaden 1898. pp. 39–72.

- ^ a b Michael Kochems (2013). Straßen- und Stadtbahnen in Deutschland. Band 14: Berlin – Teil 2. Straßenbahn, O-Bus. EK-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2013. p. 163. ISBN 978-3-88255-395-6.

- ^ Wolfgang Kramer; Siegfried Münzinger. "Südliche Berliner Vorortbahn". Berliner Verkehrsblätter, 1963. pp. 59–61.

- ^ "Berliner Linienchronik". www.berliner-linienchronik.de. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Berliner Straßenbahn (berlin-straba.de)". berlin-straba.de. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

Further reading

edit- Cornelia Hüge (2001), Die Karl-Marx-Straße. Facetten eines Lebens- und Arbeitsraums, Kramer, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-87956-271-7

- Lothar Uebel, Karstadt am Hermannplatz. Ein gutes Stück Berlin, Hrsg: Karstadt Warenhaus AG. 2000

External links

edit- Commons: Hermannplatz (Berlin-Neukölln) - Collection of images, videos, and audio files

- Hermannplatz: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstadt educational association (near Kaupert)

- Axel Mauruszat: berlin-hermannplatz.de with more information about Hermannplatz