This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Franz Carl Heimito, Ritter von Doderer, known as Heimito von Doderer (German pronunciation: [haɪ̯ˈmiːto fɔn ˈdoːdəʁɐ]; 5 September 1896 – 23 December 1966), was an Austrian writer.

Heimito von Doderer | |

|---|---|

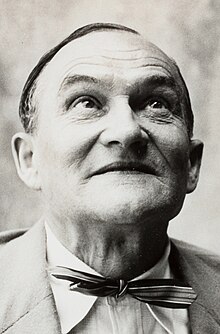

Heimito von Doderer in 1959 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 5, 1895 Hadersdorf-Weidlingau, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 23 December 1966 (aged 71) |

| Political party | NSDAP (1936-1945) |

| Other political affiliations | DNSAP (1933) |

| Spouse(s) | Gusti Hasterlik (1930-1938) Emma Maria Thoma (1952-1966) |

| Occupation | Writer |

Family

editHeimito von Doderer was born in Weidlingau, which has been part of the 14th District of Vienna since 1938, in a forester's lodge where his family stayed while his father, the architect and engineer Wilhelm Carl (Gustav), Ritter von Doderer (1854, Klosterbruck (Czech: Loucký klášter), Znaim – 1932, Vienna) worked on the regulation of the Wien River. The lodge was not preserved; today a memorial marks the site. Wilhelm Carl Doderer also worked on the construction of the Tauern Railway, the Kiel Canal and the Wiener Stadtbahn public transport network. His brother Richard (1876–1955) and his father Carl Wilhelm (Christian) Ritter von Doderer (1825, Heilbronn –1900, Vienna; ennobled in 1877) were also noted architects and industrialists. Carl Wilhelm's wife Maria von Greisinger (1835–1914) was related through her mother to the Austrian poet Nikolaus Lenau.

Doderer's mother, Wilhelm Carl's wife Louise Wilhelmine "Willy" von Hügel (1862–1946), was the daughter of the established German building contractor Heinrich von Hügel (1828–1899), who had worked with her later husband on several railway projects. Her sister Charlotte married Max Freiherr von Ferstel (1859, Vienna – 1936, Vienna), son of Heinrich von Ferstel, architect of the Vienna Votive Church. Max von Ferstel designed the plans for the Doderer family home in the Vienna Landstraße district.

Until World War I, the Doderer family ranked among the wealthiest industrial dynasties of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Heimito was the youngest of six children. His unusual first name was a German phonetic spelling of the Spanish name Jaimito, a diminutive of Jaime (James). As Louise Wilhelmine was Protestant, her children likewise were baptised Protestant, although they grew up in a mainly Catholic environment.

Life and work

editHeimito von Doderer spent most of his life in Vienna, where he attended the gymnasium (secondary school) with moderate success. He spent his summers in his family's retreat in Reichenau an der Rax. The adolescent entered into a homoerotic romantic affair with his home tutor and gained bisexual and sadomasochistic experiences as a frequent brothel visitor. In 1914, he narrowly passed his matura exams and enrolled to study law at the University of Vienna; however, in April 1915 he joined the dragoon regiment No. 3 of the Austro-Hungarian Army and served in the mounted infantry at the Eastern Front in Galicia and Bukovina. On 12 July 1916 (during the Brusilov Offensive) he was captured as a prisoner of war by the Imperial Russian Army in the area of Tlumach.

A long way from home, in a Russian Far East camp for officer POWs in Krasnaya Rechka near Khabarovsk, he decided to become an author and began writing. Upon the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk he was released by the Bolshevik government but had to make his way back to Austria through the Russian Civil War. Stranded in Samara, Doderer and his comrades again turned to the East, finding refuge in a Red Cross camp near Krasnoyarsk, cared for by Elsa Brändström. Many men had died from typhoid fever during their flight. Doderer stayed in Siberia until his eventual return to Austria in 1920; he finally reached Vienna on 14 August.

His first published work, the book of poems Gassen und Landschaft ("Streets and countryside"), appeared in 1923, followed by the novel Die Bresche ("The breach") in 1924, both with little success. A second novel, Das Geheimnis des Reichs ("The secret of the empire"), was published in 1930. In the same year he married Gusti Hasterlik, but they separated two years later and were divorced in 1938.

In 1933 Doderer joined the Austrian section of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and published several stories in the Deutschösterreichische Tages-Zeitung ("German-Austrian Daily"), a newspaper closely linked to the party and promoting racism and the incorporation of Austria into Nazi Germany. In 1936 he moved to Dachau, Germany, where he met Emma Maria Thoma, who would become his second wife in 1952. In Germany, he renewed his NSDAP membership (the Austrian Nazi Party had been banned since 1933). He returned to Vienna in 1938, sharing a flat with the celebrated painter Albert Paris Gütersloh. In that year his novel Ein Mord, den jeder begeht (Every Man a Murderer) was published. He converted to Catholicism in 1940 as a result of his reading of Thomas Aquinas and his alienation from the Nazis, which had been growing for some years. Also in 1940, Doderer was called up to the Wehrmacht and was later posted to German-occupied France, where he began work on his most celebrated novel Die Strudlhofstiege (the name refers to the so-called Strudlhofstiege, an outdoor staircase in Vienna). Due to ill health, he was allowed in 1943 to return from France, serving in the Vienna area, before a final posting to Oslo at the end of the war.

After his return to Austria in early 1946, he was banned from publishing until 1947. He continued work on Die Strudlhofstiege, but although he completed it in 1948, the still-obscure author was unable to get it published immediately. However, when it did finally appear in 1951, it was a huge success, and Doderer's place in the post-war Austrian literary scene was assured. Doderer subsequently returned to an earlier unfinished project, ''Die Dämonen ("The demons"), which appeared in 1956 to much acclaim. In 1958 he began work on what was intended to be a four-volume novel under the general title of Roman Nr. 7 ("Novel No. 7"), to be written as a counterpart to Beethoven's Seventh Symphony. The first volume Die Wasserfälle von Slunj, appeared in 1963; the second volume, Der Grenzwald, was to be his last work and was published, incomplete and posthumously, in 1967. Doderer died in Vienna of intestinal cancer on 23 December 1966.

Bibliography

editNovels

edit- Die Bresche (1924). The Breach

- Das Geheimnis des Reichs (1930). The Secret of the Empire, trans. John S. Barrett (1998)

- Ein Mord, den jeder begeht (1938). Every Man a Murderer, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (1964)

- Ein Umweg (1940). A Detour

- Die erleuchteten Fenster oder die Menschwerdung des Amtsrates Julius Zihal (1951). The Lighted Windows, trans. John S. Barrett (1999)

- Die Strudlhofstiege oder Melzer und die Tiefe der Jahre (1951). The Strudlhof Steps, trans. Vincent Kling (New York Review Books, 2021)

- Die Dämonen. Nach der Chronik des Sektionsrates Geyrenhoff (1956). The Demons, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (Knopf, 1961)

- Die Merowinger oder die totale Familie (1962). The Merowingians, trans. Vinal Overing Binner (1996)

- Roman Nr.7/I. Die Wasserfälle von Slunj (1962). Novel No. 7/I: The Waterfalls of Slunj, trans. Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1966)

- Roman No. 7/II. Der Grenzwald (1967, posthumous). Novel No. 7/II: The Border Forest

Novellas and short stories

edit- Das letzte Abenteuer (novella) (1953). The Last Adventure

- Die Posaunen von Jericho (novella) (1958). The Trumpets of Jericho

- Die Peinigung der Lederbeutelchen (short stories) (1959). The Torment of the Leather Purse

- Unter schwarzen Sternen (short stories) (1966). Under Black Stars

- Meine neunzehn Lebensläufe und neun andere Geschichten (short stories) (1966). My Nineteen Curricula Vitae and Nine Other Stories

- Frühe Prosa: Die Bresche; Jutta Bamberger; Das Geheimnis des Reichs (early prose) (1968, posthumous)

- Die Erzählungen (collected short stories) (1972, posthumous)

- The Writing of Heimito von Doderer: Including First English Translations of The Strudlhof Steps, The Trumpets of Jericho, Under Black Stars (1974). Translations by Vincent Kling in Chicago Review, vol. 26, no. 2[1]

- A Person Made of Porcelain and Other Stories (2005). Selected compilation of short stories translated by Vincent Kling.

- Seraphica; Montefal (two early stories) (2009, posthumous)

Poetry

edit- Gassen und Landschaft (1923). Streets and Countryside

- Ein Weg im Dunkeln (1957). A Path in the Dark

Essays, diaries and letters

edit- Der Fall Gütersloh (monograph on the painter Gütersloh) (1930)

- Grundlagen und Funktion des Romans (essay) (1959). Principles and Function of the Novel

- Tangenten: Tagebuch eines Schriftstellers 1940 – 1950 (diaries) (1964)

- Repertorium. Ein Begreifbuch von höheren und niederen (1969, posthumous). An ABC of Ideas and Concepts

- Die Wiederkehr der Drachen (essays) (1970, posthumous). The Return of the Dragons

- Commentarii 1951 bis 1956: Tagebücher aus dem Nachlaß (diaries) (1976, posthumous)

- Commentarii 1957 bis 1966: Tagebücher aus dem Nachlaß (diaries) (1986, posthumous)

- Heimito von Doderer / Albert Paris Gütersloh: Briefwechsel 1928 – 1962 (letters) (1986, posthumous)

- Die sibirische Klarheit (early texts from years in Russia) (1991, posthumous). Siberian Light

- Tagebücher 1920 – 1939 (diaries) (1996, posthumous)

- Gedanken über eine zu schreibende Geschichte der Stadt Wien (essay) (1996, posthumous). Thoughts About an Unwritten History of Vienna

- Von Figur zu Figur (letters to Ivar Ivask) (1996, posthumous)

Decorations and awards

edit- 1954 Literature Prize for Prose from the Cultural Committee of German Business within the Federation of German Industries

- 1957 Grand Austrian State Prize for Literature

- 1961 Literary Prize of the City of Vienna

- 1966 Wilhelm Raabe Prize

- 1966 Ring of Honor of the City of Vienna

References

edit- ^ "Vol. 26, No. 2, 1974 of Chicago Review on JSTOR". www.jstor.org. Retrieved 26 November 2021.