Hebao (Chinese: 荷包; pinyin: hébāo), sometimes referred as Propitious pouch in English,[1] is a generic term used to refer to Chinese embroidery pouches, purses, or small bags.[2]: 83 [3]: 84 When they are used as Chinese perfume pouch (or sachet), they are referred as xiangnang (Chinese: 香囊; pinyin: xiāngnáng; lit. 'Fragrant sachet'), xiangbao (Chinese: 香包; pinyin: Xiāngbāo; lit. 'Fragrant bag'), or xiangdai (Chinese: 香袋; pinyin: xiāngdài).[4][1][3]: 216 In everyday life, hebao are used to store items. In present-days China, xiangbao are still valued traditional gifts or token of fortune.[1] Xiangbao are also used in Traditional Chinese medicine.[5]: 463

| Hebao | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

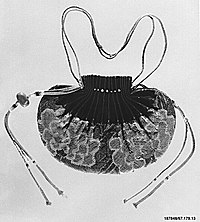

Hebao, Qing dynasty, 19th century | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 荷包 | ||||||

| |||||||

| English name | |||||||

| English | Propitious pouch | ||||||

There are many ethnic groups in China which share the custom of wearing pouches. The hebao is also a type of adornment used in traditional Chinese clothing (including in hanfu and in the Manchu people's qizhuang).[4][1] Manchu pouches are called fadu.[1]

Terminology

editWhile the wearing of Chinese pouches can be traced back to the Pre-Qin dynasties or much earlier, the term of hebao only appeared after the Song dynasty.[1]

Cultural significance

editToken of love

editHebao is also used as token of love since purses were personal items.[6]: 100 They are used as a gift between young girls and boys and their acceptance towards each other.[2]: 83 Chinese perfume pouches, xiangbao, are still valued items which are exchanged between lovers in the countryside.[4]

Perfume pouches are also a love token for the ethnic Manchu; and when two youths fall in love, the boy is given a handmade perfume pouch by the girl.[1] It is unknown when the perfume pouch became a pledge of romantic love.[1] In Manchu culture, the pouch can also hold tobacco. Tobacco pouches are usually made by a wife for her husband or by a maiden for her lover.[1]

It is also customary for the brides from the Yunnan ethnic minorities to sew hebao in advance prior to their wedding; they would then bring hebao to their bridegroom's home when they get married.[6]: 100 The number of hebao they would require to make would depend on the numbers of people (e.g. musicians, singers and guests) who would attend their wedding ceremony.[6]: 100 Ginkgo nuts, peanuts, sweets would be placed inside those pouches as a symbolism of 'giving birth to babies as soon as possible'.[6]: 100–101

Perfume pouches against the Five poisons

editOn the Dragon Boat Festival, Chinese mugwort would often be inserted in the hebao to exorcise the Five Poisons. These perfume sachets are called xiangbao (香包).

Medical usage

editXiangbao is used in Traditional Chinese medicine.[5]: 463 The wearing of Chinese medicine xiangbao as a preventive to diseases are a characteristic of Traditional Chinese medicine, known as dressing therapy.[5]: 463 These medicine pouches are used to induce resuscitation, awaken consciousness, eliminate turbid pathogens with aromatics, invigorate organs (spleen and stomach), avoid plague and filth, repel mosquitoes and other insects.[5]: 463

History

editHebao

editThe hebao was developed from the nangbao, a type of small bag which would keep one's money, handkerchief and other small items as ancient Chinese clothing did not have any pockets.[1] The most common material for the making of nangbao was leather.[1] The earliest nangbao had to be carried by hand or by back, but with time, the nangbao was improved by people by fastening it to their belts as the earliest nangbao were too inconvenient to carry.[1]

The custom of wearing of pouches dates back to the pre-Qin dynasties period or earlier; the earliest unearthed artefacts of Chinese pouches is one dating from the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period.[1][note 1]

In the Southern and Northern dynasties, hebao became one of the most popular form of clothing adornment. They were worn at the waist and were used to carry items (such as seals, keys, handkerchiefs). Incense, pearls, jade, and other valuable items were placed inside the hebao to dispel evil spirits and foul smells.[7]

In the Song dynasty, the term hebao referred to a small bag which would store carry-on valuables (e.g. money and personal seal).[1] Since then, the custom of wearing hebao continued throughout the centuries through the late Qing dynasty and the early Republic of China. It then vanished in cities due to the clothing reforms when pockets became of common use.[1] Despite its decline in common use, the hebao was still popular in some rural areas and ethnic minority areas in present-day China allowing the Chinese folk art to be transmitted to modern times.[1]

Chinese perfume pouches/ xiangbao/ xiangnang/ xiangdai

editIt is also likely that the use of xiangbao is a custom which dates back to ancient times traditions, when people in ancient times used to carry a medicine bags when they would go hunting in order to drive poisonous insects away.[4][1]

The tradition of carrying xiangbao can be traced back to the Duanwu festival, where a hebao would be filled with fragrant herbs and was embroidered with the patterns of the Five Poisons; it was meant to ward off evil spirits and wickedness while brings wealth and auspiciousness to its carrier.[1] According to old sayings, these perfume pouches were made to commemorate Qu Yuan: when Qu Yuan drowned himself in the Miluo River, people living in the neighbouring Qin made and carried pouches stuffed with sweet grass and perfumed which was loved by Qu Yuan out of sympathy for the poet and to cherish his memory.[4]

According to the Neize of the Liji《禮記•内则》, young people have to wear a scented bag, called jinying (衿纓), during this period, when they meet their parents to meet their parents to pay respect.[6]: 100 [8][5]: 463

During the reign of Qin Shi Huang, perfume pouches were attached on the girdles of young men to show respect to their parents and their in-laws.[9]: 87

It is also believed that the use of xiangbao is a long tradition of the Han Chinese; the use of xiangbao can be traced back to the Tang dynasty when women living in rural areas would make perfume pouch (made of coloured silk, silk threads, gold and silver beads) in every year on the 4th lunar month.[4]

By the Qing dynasty, xiangbao were not exclusively used on the Duanwu Festival; they were used on daily basis.[1][4] Nearly everyone carried a xiangbao regardless of social classes, ages and gender.[9]: 87 The Manchu also carried xiangbao all year round.[9]: 87 Moreover, according to the Qing dynasty custom, the emperors and the empresses were required to carry a xiangbao on them all year round. The Qing emperors would also award perfume pouches to the princes and ministers to show his favour for them on important festivals or at the end of each year.[4][1] Yuyong hebao (Chinese: 御用荷包; pinyin: yùyòng hébāo), ornamented purses which were manufactured for the imperial palace, were an extraordinary mark of imperial favour and expressed the high regards which was held by the Qing emperor to his generals; the emperors only sent to those hebao to his highest generals.[10]: 413

Emperor Tongzhi and Emperor Guangxu used to perfume pouches when choosing their empresses: the Emperor would hang a xiangbao on the button of the dress of the girls whom he took fancy in after having examined all the girls who were lined up in front of him.[4] Xiangbao were used extensively by the common people regardless of gender and ages; they would carry perfume pouches and give it to others as presents while young men and women would often use it as a toke of love.[4] Xiangbao were appreciated for their fragrance but they were also considered as a preventive against diseases.[9]: 87

Manchu pouch/ fadu

editThe fadu of the Manchu people originated from a form of bag used by the ancestors of the Manchu who lived a hunting life through dense forested mountains. The bag was originally made of out animal hide and was worn at the waist; it was secured on the belt for the usage of carry food.[1] Later on, when the ancestors of the Manchu left the mountain regions and began an agricultural life, the hide bag was developed into a small and delicate accessory which would only contain sweetmeat.[1] Manchu women would use small pieces of silk and satin to the sew the bag and would decorate it with flower and birds embroidery patterns.[1] They also use their pouches to carry perfume and tobacco.[1]

Construction and design

editHebao is a bag composed of 2 sides: the interior and exterior side.[1] It is often embroidered on its outside while the inside is made of a thick layer of fabric.[1] The opening of the bag is threaded with a silk string that can tightened and loosened.[1] They are made in various shapes, such as rotund, oblong, peach, ruyi, and guava.[1] They also have different patterns for different usages (e.g. butterflies and flowers represented the wish for love and marriage; golden melons and children represented the wishes for longevity and more children; images of qilin represented the wishes for carrying a son).[1] Each areas in China have a distinctive forms of hebao.[1]

Manchu's tobacco pouch

editThe Manchu people's tobacco pouch is tied with a small wooden gourd which is carved with rich patterns. The gourd acts primarily as a fastener to prevent its carrier from losing his pouch, by making it harder for the fastener to slip from the seam between the waist and the cloth belt which was used by the Manchu people in the past.[1]

Yuyong hebao

editYuyong hebao (Chinese: 御用荷包; pinyin: yùyòng hébāo) were the ornamented purses made for the imperial palace and were bestowed to the highest generals favoured by the Emperor in the Qing dynasty as a symbol of favour and high regards.[10]: 413 They usually came into 2 sizes: either large or small.[10]: 413 They could be bestowed as a single purse, in pairs, or in numbers up to 4.[10]: 413 These hebao could also contains gems, jewels and precious metals, such as shanhu (corals), qizhen babao (lit. "seven pearls and eight jewels"), jinding (gold ingot), yinding (silver ingots), jinqian (gold coins) and yinqian (silver coins).[10]: 413–414

Ways of wearing

editManchu ethnic

editManchu people regardless of gender wore pouches, but they wore it differently according to their gender. Men wore their pouches at the waist while women tied their pouches to the 2nd buttons of their traditional Manchu dress, qizhuang.[1]

Popular culture

editLiterature and stories

editIn the Dream of the Red Chamber, a hebao is personally made by Daiyu and is given to Baoyu as an expression of her love for him; however, she misunderstood that Baoyu had deliberately given the purse away and destroyed the other hebao that she was making.[6]: 100 In reality, Baoyu treasured the hebao so much that he would have never given it away.[6]: 100

Music and songs

editXiuhebao (Chinese: 绣荷包; lit. 'Embroidering a pouch'), originally called Huguang diao from the regions of Hunan and Guangdong, is a popular song since the Ming and Qing dynasties.[2]: 83 Chinese folks about embroidering hebao are sung in all parts of China, with the most familiar ones being the ones in Shanxi, Yunnan, and Sichuan.[2]: 83 These songs depict the thoughts of young girls who miss their lovers and are personally embroidering a hebao for their beloved.[2]: 83

Similar items

edit- Qiedai - Eggplant-shaped purses worn by imperial officials in ancient China.[7]

- Qingyang sachet

- Sachet

- Yudai - Fish-shaped tally bag; a pouch used in ancient China as a form of yufu (fish tally).[7]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ This is according to the 2011 source article

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "Propitious pouch". europe.chinadaily.com.cn. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Jin, Jie (2011). Chinese music. Li Wang, Rong Li (Updated ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-18691-9. OCLC 671710042.

- ^ a b Wanlong, Gao, Dr (2012). A handbook of chinese cultural terms. [Place of publication not identified]: Trafford On Demand Pub. ISBN 978-1-4669-2005-7. OCLC 781378256.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Culture of Chinese small living goods - chinaculture". en.chinaculture.org. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e The 2021 International Conference on Machine Learning and Big Data Analytics for IoT Security and Privacy : SPIoT-2021. Volume 1. J. D. MacIntyre, Jinghua Zhao, Xiaomeng Ma. Cham. 2022. ISBN 978-3-030-89508-2. OCLC 1282170023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Chinese auspicious culture. Evy Wong (English ed.). Singapore: Asiapac Books. 2012. ISBN 978-981-229-642-9. OCLC 818922837.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c "Clothes Never Enough". www.china.org.cn. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Legge, James. "《內則 - Nei Ze》". Ctext.org.

Youths who have not yet been capped, and maidens who have not yet assumed the hairpin, at the first crowing of the cock, should wash their hands, rinse their mouths, comb their hair, draw over it the covering of silk, brush the dust from that which is left free, bind it up in the shape of a horn, and put on their necklaces. They should all bang at their girdles the ornamental (bags of) perfume; and as soon as it is daybreak, they should (go to) pay their respects (to their parents) and ask what they will eat and drink. If they have eaten already, they should retire; if they have not eaten, they will (remain to) assist their elder (brothers and sisters) and see what has been prepared. [男女未冠笄者,雞初鳴,咸盥漱,櫛縰,拂髦總角,衿纓,皆佩容臭,昧爽而朝,問何食飲矣。若已食則退,若未食則佐長者視具。]

- ^ a b c d Davis, Nancy E. (2019). The Chinese lady : Afong Moy in early America. New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-093727-0. OCLC 1089978299.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Money in Asia (1200-1900) : small currencies in social and political contexts. Jane Kate Leonard, Ulrich Theobald. Leiden. 2015. ISBN 978-90-04-28835-5. OCLC 902674191.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link)