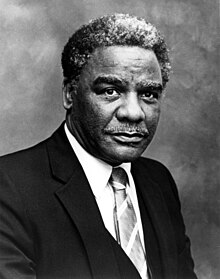

The Harold Washington Party was founded in Chicago in the late 1980s by Timothy C. Evans to represent the interests of the city's African-American population who felt disenchanted with the mainline Democratic Party.[1]

History

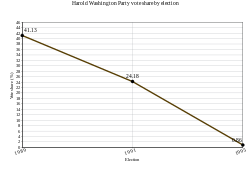

editThe party was created ahead of the 1989 special elections to fill the mayoral vacancy in Chicago created when Harold Washington, Chicago's first black mayor, died in office. It nominated a candidate for the 1989 special election for Chicago mayor as well as and several other offices in Cook County. The party's nominee in the 1989 special election, Timothy C. Evans received 41% of the vote.

In 1990, ahead of the Cook County elections, a court decision denied Harold Washington Party nominees ballot access, which was reported a boon to the Democratic Party slate. Ballot access was later reinstated though it required a jury-rigged solution to vote for their candidates because of how close to the election the decision was reached.[2][3]

Additionally, R. Eugene Pincham left the Democratic Party and joined the Harold Washington Party after losing the Democratic nomination for President of the Cook County Board of Commissioners. The party did not do as well as they did during the 1989 special election but candidates for major offices such as County Clerk or Sheriff got around 8-16% of the vote, and the party received 10% of the total vote for Cooky County Commissioner seats, which did not gain them any seats.[4]

James R. Hutchinson, the party's vice-chairman, was going to be the party's candidate for the 1991 Chicago mayoral election, if Danny K. Davis secured the Democratic nomination; this did not happen and so Hutchinson stepped down so Pincham could be the party's mayoral candidate. Pincham received the endorsement of Davis shortly afterwards. The party wanted to expand their appeal and added white candidates such as Larry Machaj, a Polish-American businessman, to their slate.[5] Despite the change in candidates, Richard M. Daley won in a landslide against Pincham with him under-performing expectations. Daley increased his average vote share in predominately African American wards from nine to fifteen percent from the primary to the general election. Overall, Daley received 25% of the African American vote, including over 40% in two predominately African American wards.[6]

The following few years were chaotic for the party. In 1992, a dispute over a deal between the party and the Hudepohl-Schoenling Brewing Co., makers of Mt. Everest malt liquor, displeased half of the party. The brewery would donate 25 cents per case sold in African American neighborhoods in Chicago towards community projects. Joseph Faulkner, the party's Chicago's 8th Ward committeeman, criticized the move as a deal that will increase malt liquor sales in the community for the financial gain of party officials. Reed, the leader of the party, stating this was a way to reinvest part of the millions spent on malt liquor in the community.[7] During the 1992 County elections the party fielded only a single candidate: Doloris Jones for Clerk of the Circuit Court, who finished in a distant third place with 6.97% of the vote.[8] Shortly afterwards, Pincham left the party over a Republican-backed loan taken for the party. Hutchinson denied any ties to the Republican Party.[9] At the end of 1993 the party suffered a schism between the Progressive Independents of the Harold Washington Party, headed by Bruce Crosby, and the Harold Washington Party, headed by David Reed. The former viewed Reed's decision to endorse non-party candidates as treasonous.[10]

Up until the 1994 County elections, the Harold Washington Party never had primaries to decide on candidates, but since Crosby and Reed both ran for the Harold Washington Party nomination for President of the Cook County Board of Commissioners there needed to be one. Infighting occurred within the party during the election cycle with Baker, a member of the Progressive Independents of the Harold Washington Party, calling fellow party member Tyler a Republican in disguise. [11] The party fielded more candidates than the previous election this cycle, but they were still a distant third place in each election they participated in.

From this point on the Harold Washington Party would gain few votes. The party's candidate, Lawrence C. Redmond, had less than one percent of the vote in the 1995 Chicago mayoral election, and the 1996 County elections were the final elections for which the party fielded a candidate.

References

edit- ^ Belsie, Laurent (July 16, 1990). "Dissatisfied Chicago Blacks Form New Party". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Mount, Charles; Thomas Hardy (September 21, 1990). "Judge Drops Harold Washington Party From Ballot". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Grady, William (October 26, 1990). "WASHINGTON PARTY IS BACK ON BALLOT". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ "OFFICIAL FINAL RESULTS GENERAL ELECTION COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 1990" (PDF). voterinfo.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008.

- ^ "HAROLD WASHINGTON PARTY TABS PINCHAM TO FACE DALEY". Chicago Tribune. March 4, 1991. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Green, Paul M. (June 1991). "Chicago's 1991 mayoral elections: Richard M. Daley wins second term". Illinois Issues (Now NPR Illinois). Springfield, Illinois: University of Illinois Springfield.

- ^ "MALT LIQUOR DEAL SPLITS PARTY STAFF". Chicago Tribune. July 24, 1992. Retrieved September 8, 2024.

- ^ "OFFICIAL FINAL RESULTS GENERAL ELECTION COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 1992" (PDF). voterinfo.net. Cook County Clerk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008.

- ^ "PINCHAM CUTS HIS TIES TO WASHINGTON PARTY". Chicago Tribune. December 22, 1992. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ "WASHINGTON PARTY SPLIT MAY BE A SIGN OF HEALTH". Chicago Tribune. December 23, 1993. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ "WASHINGTON PARTY MIXING SIGNALS". Chicago Tribune. February 18, 1994. Retrieved August 24, 2024.