Harold Stirling Vanderbilt CBE (July 6, 1884 – July 4, 1970) was an American railroad executive, a champion yachtsman, an innovator and champion player of contract bridge, and a member of the Vanderbilt family.[1]

Harold Stirling Vanderbilt | |

|---|---|

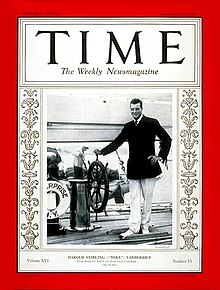

Vanderbilt at the helm of his J-class yacht Enterprise (Time, September 15, 1930) | |

| Mayor of Manalapan, Florida | |

| In office 1952–1966 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 6, 1884 Oakdale, New York |

| Died | July 4, 1970 (aged 85) Newport, Rhode Island, US |

| Spouse | |

| Parents | |

| Education | St. Mark's School Harvard Law School |

| Alma mater | Harvard College |

| Occupation | |

Early life

editHe was born in Oakdale, New York, the third child of William Kissam Vanderbilt and Alva Erskine Smith. To family and friends he was known as "Mike". His siblings were William Kissam Vanderbilt II and Consuelo Vanderbilt.[1]

His maternal grandfather was Murray Forbes Smith. As the great-grandson of the shipping and railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, he was born to great wealth and privilege; as a child he was raised in Vanderbilt mansions, traveled frequently to Europe, and sailed the world on yachts owned by his father. His nephew, Barclay Harding Warburton III, founded the American Sail Training Association.[2]

Vanderbilt was educated by tutors and at private schools in Massachusetts, including St. Mark's School, Harvard College (AB 1907), and Harvard Law School, which he attended from 1907 to 1910.[1]

Career

editAfter Harvard Law, he joined the New York Central Railroad, the centerpiece of his family's vast railway empire, of which his father was president.[1]

On his father's death in 1920, Harold inherited a fortune that included the Idle Hour country estate at Oakdale, New York (on Long Island) and equity in several railway companies, including Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Railroad, the Genesee Falls Railway, the Kanawha and Michigan Railway, the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad, the New Jersey Junction Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad and the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad.

Following the death of his brother William in 1944, he remained the only active representative of the Vanderbilt family involved with the New York Central Railroad. He served as a director and member of the executive committee until 1954, when the New York Central was subjected to a hostile takeover by business tycoon Robert R. Young.[1] Young committed suicide four years later.

World War I

editVanderbilt nearly lost his yacht, the Vagrant, on Britain's entry into the First World War. The British competitor for the 1914 America's Cup, Shamrock IV, was crossing the Atlantic with the steam yacht Erin, destined for Bermuda, when Britain declared war on Germany on August 5, 1914. The British crews received word of the declaration of war by radio. As the commodore of the New York Yacht Club, Vanderbilt sent the Vagrant from Rhode Island to Bermuda to meet the Shamrock IV and Erin, and to escort them to the US. Meanwhile, among the first things done in Bermuda on the declaration was to remove all maritime navigational aids. The Vagrant arrived on the 8th. Having no radio, the crew were unaware of the declaration of war and finding all of the buoys and other navigational markers missing, they attempted to pick their own way in through the Narrows, the channel that threads through the barrier reef. This took them directly to the fore of St. David's Battery, where the gunners were on a war footing and opened fire. This was just a warning shot, which had the desired effect. The Shamrock IV and Erin arrived the next day. The America's Cup was cancelled for that year.

In March 1917, Vanderbilt was commissioned a lieutenant (junior grade) in the United States Naval Reserve. When the United States entered World War I, he was called to active duty on April 9, 1917, and assigned as commanding officer of the scout patrol boat USS Patrol No. 8 (SP-56), which operated out of Newport, Rhode Island. He was reassigned on July 20 to command the Block Island, Rhode Island, anti-submarine sector and on November 17 the New London, Connecticut, sector. While at Block Island, one of his subordinates was Chief Machinist Mate Harold June who would go on to serve as a pilot with Commander (later admiral) Richard E. Byrd's 1929 Antarctic Expedition. June was one of four men who were aboard the first aircraft to fly over the South Pole. Upon Vanderbilt's reassignment, the officers and men of the Block Island sector presented him with an engraved naval officer's sword as a token of their esteem. The sword is now displayed at the Marble House in Newport.

On July 17, 1918, he was reassigned to the US Navy forces in Europe and reported to Submarine Chaser Detachment 3 at Queenstown, Ireland, in August. He served with Detachment 3 until the unit was disbanded on November 25, 1918 – shortly after the Armistice was signed. He was placed on inactive duty December 30, 1918, and was promoted to lieutenant on February 26, 1919, retroactive to September 21, 1918. He was discharged from the Naval Reserve on March 26, 1921.[3]

Sailing career

editAs a boy, Harold Vanderbilt spent part of his summers at the Vanderbilt mansions—the Idle Hour estate in Long Island, New York, on the banks of the Connetquot River; Marble House at Newport, Rhode Island; and later at Belcourt, the Newport mansion of his stepfather, Oliver Belmont. As an adult, he pursued his interest in yachting, winning six King's Cups and five Astor Cups at regattas between 1922 and 1938. He served as commodore of the New York Yacht Club from 1922 to 1924.[4] In 1925, he built his own luxurious vacation home at Palm Beach, Florida, that he called "El Solano". (John Lennon, formerly of the Beatles, purchased it[clarification needed] shortly before his 1980 murder.)

Vanderbilt achieved the pinnacle of yacht racing in 1930 by defending the America's Cup in the J-class yacht Enterprise. His victory put him on the cover of the September 15, 1930, issue of Time magazine (see image above). In 1934 Harold faced a dangerous challenger from the United Kingdom, Endeavour, owned by the aviation pioneer and industrialist Thomas Sopwith. Endeavour won the first two races but Vanderbilt's Rainbow then won four races in a row and successfully defended the Cup. In 1937 he won again in Ranger, the last of the J-class yachts to defend the Cup. He was posthumously elected to the America's Cup Hall of Fame in 1993.

In the fall of 1935, Harold began a study of the yacht racing rules with three friends: Philip Roosevelt, president of the North American Yacht Racing Union (predecessor to US Sailing); Van Santvoord Merle-Smith, president of the Yacht Racing Association of Long Island Sound; and Henry H. Anderson. "The four men began by attempting to take the right-of-way rules as they were and amending them. After about six weeks of intensive effort, they finally concluded that they were getting exactly nowhere. It was the basic principles, not the details, that were causing the problems. They would have to start from scratch."[5]

In 1936, Vanderbilt, with assistance from the other three had developed an alternative set of rules, printed them, and mailed a copy to every yachtsman that he knew personally or by name in both the United States and England. These were virtually ignored, but a second edition in 1938 was improved, as were following versions. Vanderbilt continued to work with the various committees of the North American Yacht Racing Union until finally in 1960 the International Yacht Racing Union (predecessor to the International Sailing Federation or ISAF) adopted the rules that Vanderbilt and the Americans had developed over the previous quarter century.

Bridge

editVanderbilt was also a card game enthusiast. In 1925, while on board SS Finland, he originated changes to the scoring system through which the game of contract bridge supplanted auction bridge in popularity.[6] Three years later he endowed the Vanderbilt Cup awarded to the winners of the North American team-of-four championship (now the Vanderbilt Knockout Teams, or simply "the Vanderbilt", one of the North American Bridge Championships marquee events). In 1932, and again in 1940, he was part of a team that won his own trophy; it remains one of the most prized in the game. Vanderbilt also donated the World Bridge Federation Vanderbilt Trophy, awarded from 1960 to 2004 to the winner of the open category at the quadrennial World Team Olympiad, and since 2008 to the winner of the corresponding event at the World Mind Sports Games.[7][8]

Vanderbilt invented the first strong club system, which he called the "Club Convention" but which has since become more usually known as the Vanderbilt Club.[9][10] The strong club, or forcing club, family of bidding systems has performed exceptionally well in world championship play.[11] He wrote four books on the subject.

Vanderbilt, Ely Culbertson, and Charles Goren were the three people named when The Bridge World inaugurated a bridge "hall of fame" in 1964 and they were made founding members of the ACBL Hall of Fame in 1995.[12][13][a]

In 1969, the World Bridge Federation (WBF) made Vanderbilt its first honorary member.[citation needed] In 1969, he became a WBF Honorary Member, and was inducted into the ACBL Hall of Fame in 1964.[13][14][a]In 1941, he was made ACBL Honorary Member of the Year and won the Wetzlar Trophy in 1940.

He won the North American Bridge Championships twice and the Vanderbilt twice, the first in 1932 and the last in 1940. He was a runner-up at the North American Bridge Championships and during the Vanderbilt in 1937.

Later life

editIn 1930, after a property dispute with the Town of Palm Beach, Florida, Vanderbilt moved several miles south to an undeveloped area called Manalapan, where he purchased 500 feet of oceanfront property and built a mansion called Eastover.[15] In 1931, he filed papers to incorporate the Town of Manalapan and became the Town's first mayor, serving from 1952 until 1966. He was a town councilman for 32 years and was called "mayor emeritus" when he retired from public service.[16] In 1934, his sister, Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, built her own mansion on Hypoluxo Island, across the water from Eastover.[17][18]

In addition to sailing, Vanderbilt was a licensed pilot, and in 1938 he acquired a Sikorsky S-43 "Flying Boat".

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Vanderbilt's yachts Vagrant and Vara, which was under construction, were seized by the United States Navy. The Vagrant was designated as YP-258 and later as PYc-30. Navy official Edmond J. Moran met with Vanderbilt in New York, to present him with a check for $300,000 as compensation for the Vara. Upon receiving the check, Vanderbilt signed it over to the USO, so the money could be used to benefit servicemen.[19] The Vara was completed, renamed as the USS Valiant, and designated as PC-509 (later as PYc-51).

Personal life

editVanderbilt married Gertrude Lewis Conaway, of Philadelphia, in 1933. They had no children.[1]

Death and burial

editHarold Stirling Vanderbilt died on July 4, 1970.[1] Ironically, this was only two weeks after the Penn Central Railroad, successor to the New York Central Railroad, had declared bankruptcy (on June 21, 1970). He and his wife are interred at Saint Mary's Episcopal Cemetery in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, their graves marked with only simple flat stones. It is uncertain why he chose to be buried in Rhode Island rather than in the Vanderbilt family mausoleum on Staten Island. It is noteworthy, however, that he is buried in the same cemetery as his business rival Robert R. Young.

Legacy

editHarold Vanderbilt had a keen interest in the success of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, founded in 1873 through the financial sponsorship of his great-grandfather. A longtime member of the university's Board of Trust, he served as its president between 1955 and 1968.[20] He helped guide the institution through a time in history when racial integration of the student body was a divisive and explosive issue. In 1962, Vanderbilt attended one of the first meetings of the Vanderbilt Sailing Club and provided funding for the club to purchase its first fleet of dinghies, Penguins. The university annually offers several scholarships named in his honor, and on the grounds in front of Buttrick Hall, an approximately sixteen foot tall statue of Vanderbilt, designed by sculptor Joseph Kiselewski,[21] was erected in his honor in 1965.[20][22]

In 1947, Vanderbilt was invested as an honorary Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) by King George VI. The letters patent conferring the honor on him (signed by Queen Mary in her capacity as grand master of the order) and the insignia of the order are on display in the Trophy Room at the Marble House summer estate in Newport, Rhode Island.

In 1963, Vanderbilt assisted the Preservation Society of Newport County in acquiring Marble House in Newport, Rhode Island, which his mother had sold more than 30 years earlier. Their bid was successful, and the property was converted into a museum that has been open to the public since the mid-1960s and holds documents and artifacts related to his life.

A sailing drink, Stirling Punch, was named in Vanderbilt's honor.[23]

Vanderbilt's private railroad car, New York Central 3, was renovated and has operated luxury charter trips at the rear of regularly-scheduled Amtrak and Via Rail Canada trains.[24]

Vanderbilt was inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame in 2011.[25] He was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 2014.

Publications

edit- Contract Bridge: Bidding and the Club Convention (New York and London, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1929), 251 pp. OCLC 412630

- With "Laws of Contract Bridge, 1927, reprinted by permission of ... the Whist club: pp. 207–36."[26]

- The New Contract Bridge: Club Convention Bidding and Forcing Overbids (Scribner, 1930), 333 pp.

- Enterprise: The Story of the Defense of the America's Cup in 1930 (Scribner, 1931), 230 pp. OCLC 1625050

- "Contract by Hand Analysis: a synopsis of 1933 club convention bidding" (The Bridge World, 1933), 165 pp. OCLC 6351169

- On the Wind's Highway: Ranger, Rainbow and Racing (Scribner, 1939), 259 pp. OCLC 6351177

- The Club Convention System of Bidding at Contract Bridge, As Modernized by Harold S. Vanderbilt (Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1964), 160 pp.[27]

Notes

edit- ^ a b The Bridge World monthly magazine, established by Ely Culbertson in 1929, named nine members of its bridge hall of fame including Culbertson from 1964 to 1966, but it never named another. Almost thirty years later, the ACBL established its hall of fame with the Bridge World nine as founding members. It named eight new members in 1995 and has inducted others annually since then.[12][13]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g "Harold Vanderbilt, Yachtsman, Is Dead". The New York Times. July 5, 1970. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "Video". CNN. August 18, 1980. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ^ Who Was Who in America, 1969–1973. Vol. 5.

- ^ "Harold Vanderbilt Gets a New Air Yacht; Can Cruise at High Speed With Six Aboard". The New York Times. April 29, 1927. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ MacArthur, Robert C. Room at the Mark. (Boston, 1991).

- ^ "The BLML–SS Finland Challenge". World Bridge Federation. October 31, 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "World Team Olympiad". World Bridge Federation (WBF). Retrieved 2014-05-31. With image of the Vanderbilt Trophy.

- ^ "World Bridge Games". WBF. Retrieved 2014-05-31.

- ^ Harold S. Vanderbilt, Contract Bridge, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York & London, 1929

- ^ The Bridge Players' Encyclopaedia, International Edition, Paul Hamlyn, London, 1967, p. 564

- ^ The Nottingham Club, Neapolitan Club, Blue Club, Precision Club, and other strong forcing club systems are an outgrowth of the Vanderbilt Club. Polish Club, Unassuming Club and other weak club systems are an outgrowth from the Vienna System (Stern Austrian System, 1938).

- ^ a b Hall of Fame Archived 2014-11-24 at the Wayback Machine (top page). ACBL. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- ^ a b c "Induction by Year" Archived 2014-12-05 at the Wayback Machine. Hall of Fame. ACBL. Retrieved 2014-12-22.

- ^ "Vanderbilt, Harold" Archived 2014-05-31 at the Wayback Machine. Hall of Fame. ACBL. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- ^ Elkins, Jack (July 2, 2015). "Harold Stirling Vanderbilt: Meet the man behind Manalapan". Jack Elkins | Palm Beach Luxury Real Estate. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ Mayhew, Augustus (January 31, 2017). "Palm Beach Social Diary". New York Social Diary. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "Town of Manalapan". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ Hofheinz, Darrell (December 11, 2012). "Benjamins sell historic Casa Alva for recorded $6.8 million". Palm Beach Daily News. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "Proceedings". usni.org. June 2014.

- ^ a b "Virtual Tour: Harold Stirling Vanderbilt". Vanderbilt University. Archived from the original on December 28, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ "Sculpture". Joseph Kiselewski. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ "University Officers Praise Vanderbilt at Memorial". The New York Times. July 8, 1970. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "Stirling Punch". Drinks Mixer.

- ^ "New York Central 3". NYC-3.com.

- ^ "Harold Stirling Vanderbilt Inductee 2011". Nshof.org. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Contract bridge; bidding and the club convention". Library of Congress Catalog Record (LCC). Retrieved 2014-05-31.

- ^ The Club Convention System of Bidding at Contract Bridge. LCC. Retrieved 2014-05-31.

- Other sources

- Time. September 15, 1930.

- Harold S. Vanderbilt (1931). Enterprise the Story of the Defense of the America's Cup in 1930. Charles Scribner's sons Press.

- Harold S. Vanderbilt (1939). On the wind's highway: Ranger, Rainbow and racing. Charles Scribner's sons Press.

- "Sailing World Hall of Fame", Sailing World. April 24, 2002.

External links

edit- Citation at the ACBL Hall of Fame (archived)

- America's Cup Hall of Fame

- Vanderbilt's private rail car

- Harold S. Vanderbilt at Library of Congress, with 6 library catalog records (including 1 "from old catalog")