The Hallam Nuclear Power Facility (HNPF) in Nebraska was a 75 MWe sodium-cooled graphite-moderated nuclear power plant built by Atomics International and operated by Consumers Public Power District of Nebraska.[1] It was built in tandem with and co-located with a conventional coal-fired power station, the Sheldon Power Station.[2] The facility featured a shared turbo generator that could accept steam from either heat source, and a shared control room.

| Hallam Nuclear Power Facility | |

|---|---|

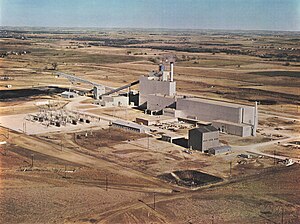

Aerial view of Hallam Nuclear Power Facility (right) and Sheldon Power Station (left) | |

| |

| Country |

|

| Coordinates | 40°33′30″N 96°47′05″W / 40.55833°N 96.78469°W |

| Status | Decommissioned |

| Construction began |

|

| Commission date |

|

| Decommission date |

|

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor supplier | |

| Power generation | |

| Nameplate capacity |

|

Full power was achieved in July 1963. The facility shut down on September 27, 1964 to resolve reactor problems. In May 1966, Consumers Public Power District rejected their option to purchase the facility from the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). In response, the AEC announced its plan to decommission the facility in June, 1966. The facility operated for 6,271 hours and generated 192,458,000 kW-hrs of electric power.[3]

It was located near Hallam, about 25 miles southwest of Lincoln.

Description

editThe sodium-cooled graphite-moderated reactor (SGR) design (of which HNFP was a demonstration) targeted economical commercial nuclear electricity. The liquid metal coolant enabled operation at temperatures sufficiently high to produce steam conditions identical to those used in fossil-fueled power plants, enhancing power conversion efficiency and making use of commodity steam turbines. It also enables low-pressure operation. The graphite moderator enabled operation with low-enriched nuclear fuel as well the potential use of the thorium fuel cycle. These benefits were expected to overcome the added complication of a using chemically reactive coolant.[4]

The reactor was initially fueled with 3.6% enriched uranium-10 molybdenum alloy with stainless steel cladding. The graphite moderator was clad in stainless steel hexagons with each corner scalloped to make room for the process tubes, which contained the fuel clusters and control rods. Three sodium heat-transfer loops (each with a radioactive primary loop and a non-radioactive secondary) moved heat to three steam generators. Steam fed into a common header to a single turbine generator. The primary hot leg temperature was 945 °F, and the secondary hot leg temperature was 895 °F.

Uranium carbide was selected for the second core at 4.9% enrichment.

Proposal, Development, and Construction

editHallam was proposed in March 1955 in response to the first round of invitations by the Atomic Energy Commission's Power Demonstration Reactor Program.[6] It used technology being developed in the smaller Sodium Reactor Experiment (SRE), also built by Atomics International. Lessons from SRE applied to HNPF include:

- Fuel rod blowing

- Poor control of sodium convection flow

- Stratification of sodium in intermediate heat exchanger

- Difficulties due to freeze-seal sodium pumps

- Difficulties in preheating of sodium systems

Because HNPF was more than ten times larger than SRE, a components development and test program were performed to provide final design data. All major components were tested, including fuel, control rods, instrumentation, pumps, and valves. The fuel handling machine was assembled and tested. Scale model of a steam generator was tested in a sodium loop along with related equipment and instrumentation.[3]

A formal three-session training program for operators was conducted in 1960. 30 personnel attended the first session for six months. Each person received approximately 900 hours of training.

Construction began on April 1, 1959. Employment during construction peaked at 270 in March 1961, and 107,600 person-days total were required to complete the construction. Various construction assembly interferences were anticipated, and detailed scale models were procured. Labor problems resulted in the loss of 1750 person-days. The entire facility was completed on November 30, 1961, 4 months past the originally planned date of completion.[3]

Operation and shutdown

editInitial criticality was achieved in January 1962, followed by wet criticality six months later. Difficulties that arose during operation and required plant shutdown and correction included leaking control rod thimbles, seizure of secondary sodium pumps, leaking steam generator instrumentation and pipe flanges, difficulty of adjusting fuel channel flow orifices, and failure of primary and secondary sodium throttle valves.

The most severe issue was the ruptures of moderator elements. Seven elements ruptured in February 1964. The ruptures and subsequent absorption of sodium into the graphite reduced the thermal neutron flux in the core and caused a reduction in local power. The moderator elements swelled as well, reducing coolant and process space. Examination disclosed that failure was caused by low ductility stress-rupture leading to a one-inch-long crack about three inches below the top of each element.

Chauncey Starr, the president of Atomics International, testified that they had identified and claimed to have fixed the issue with the moderator can. He proposed a repair operation involving attaching snorkels to each moderator can into the cover gas space, which would cost $1.8M and require 6–9 months.[7] Nonetheless, the AEC under Milton Shaw decided to terminate their contract with the utility. Consumers chose not to purchase the plant, and it was instead decommissioned.

The plant's single 75 MWe reactor operated from 1963 to September 27, 1964.[3] Decommissioning was completed in 1969. Belowground components of the reactor were entombed on-site and will have to be monitored until 2090.[8]

- Present day

Currently, the site holds a fossil-fuel plant, Sheldon Power Station. The site is monitored from 17 monitoring wells, and no radioactivity above background levels in any samples has been detected.[9]

References

edit- ^ "IAEA - Reactor Details - Hallam". IAEA. 2013-04-13. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ^ Proceedings of the Sodium Components Information Meeting. Palo Alto, California: Atomic Energy Commission. 1964-08-20. p. 10. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Burton, S.F.; Holser, A.G. (1966-10-01). Small nuclear power plants. Tid4500 (Vol 1 ed.). US Atomic Energy Commission. p. 140. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Starr, Chauncey; Dickinson, Robert (1958). Sodium graphite reactors. Addison-Wesley books in nuclear science and metallurgy. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. hdl:2027/mdp.39015003993881.

- ^ Mahlmeister, J.E. (1961-12-01). "Engineering and constructing the Hallam Nuclear Power Facility reactor structure". Atomics International. NAA (Series); SR-7366. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Atomic Energy Commission (1963-10-15). "Cooperative Power Reactor Demonstration Program". Hearings Before the United States Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, Subcommittee on Legislation, Eighty-Eighth Congress: 227. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Atomic Energy Commission (1965-08-05). "Hallam Nuclear Reactor Power Hearing". AEC Authorizing Legislation, Fiscal Year 1967.: 1051. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ State's First Nuclear Plant Buried Near Lincoln. Nebraska Energy Quarterly, Winter 1997 (archived)

- ^ "Hallam, Nebraska, Decommissioned Reactor Site Fact Sheet" (PDF). US DOE Office of Legacy Management. 4 April 2009.

External links

edit- Hallam Nuclear Power Facility (1963) – A 23-minute Atomic Energy Commission video showing the construction, fuel fabrication, and initial operation of the Hallam plant

- Hallam Nuclear Station on 1960's TV! – Additional historical images and discussion of the Hallam site and plant