Hafnium(IV) chloride is the inorganic compound with the formula HfCl4. This colourless solid is the precursor to most hafnium organometallic compounds. It has a variety of highly specialized applications, mainly in materials science and as a catalyst.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Hafnium(IV) chloride

Hafnium tetrachloride | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.463 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| HfCl4 | |

| Molar mass | 320.302 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline solid |

| Density | 3.89 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 432 °C (810 °F; 705 K) |

| decomposes[2] | |

| Vapor pressure | 1 mmHg at 190 °C |

| Structure | |

| Monoclinic, mP10[1] | |

| C2/c, No. 13 | |

a = 0.6327 nm, b = 0.7377 nm, c = 0.62 nm

| |

| 4 | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

irritant and corrosive |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

2362 mg/kg (rat, oral)[3] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Hafnium tetrafluoride Hafnium(IV) bromide Hafnium(IV) iodide |

Other cations

|

Titanium(IV) chloride Zirconium(IV) chloride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Preparation

editHfCl4 can be produced by several related procedures:

- The reaction of carbon tetrachloride and hafnium oxide at above 450 °C;[4][5]

- HfO2 + 2 CCl4 → HfCl4 + 2 COCl2

- Chlorination of a mixture of HfO2 and carbon above 600 °C using chlorine gas or sulfur monochloride:[6][7]

- HfO2 + 2 Cl2 + C → HfCl4 + CO2

- Chlorination of hafnium carbide above 250 °C.[8]

Separation of Zr and Hf

editHafnium and zirconium occur together in minerals such as zircon, cyrtolite and baddeleyite. Zircon contains 0.05% to 2.0% hafnium dioxide HfO2, cyrtolite with 5.5% to 17% HfO2 and baddeleyite contains 1.0 to 1.8 percent HfO2.[9] Hafnium and zirconium compounds are extracted from ores together and converted to a mixture of the tetrachlorides.

The separation of HfCl4 and ZrCl4 is difficult because the compounds of Hf and Zr have very similar chemical and physical properties. Their atomic radii are similar: the atomic radius is 156.4 pm for hafnium, whereas that of Zr is 160 pm.[10] These two metals undergo similar reactions and form similar coordination complexes.

A number of processes have been proposed to purify HfCl4 from ZrCl4 including fractional distillation, fractional precipitation, fractional crystallization and ion exchange. The log (base 10) of the vapor pressure of solid hafnium chloride (from 476 to 681 K) is given by the equation: log10 P = −5197/T + 11.712, where the pressure is measured in torrs and temperature in kelvins. (The pressure at the melting point is 23,000 torrs.)[11]

One method is based on the difference in the reducibility between the two tetrahalides.[9] The tetrahalides can in be separated by selectively reducing the zirconium compound to one or more lower halides or even zirconium. The hafnium tetrachloride remains substantially unchanged during the reduction and may be recovered readily from the zirconium subhalides. Hafnium tetrachloride is volatile and can therefore easily be separated from the involatile zirconium trihalide.

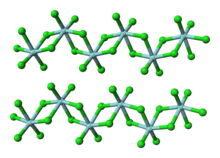

Structure and bonding

editThis group 4 halide contains hafnium in the +4 oxidation state. Solid HfCl4 is a polymer with octahedral Hf centers. Of the six chloride ligands surrounding each Hf centre, two chloride ligands are terminal and four bridge to another Hf centre. In the gas phase, both ZrCl4 and HfCl4 adopt the monomeric tetrahedral structure seen for TiCl4.[12] Electronographic investigations of HfCl4 in gas phase showed that the Hf-Cl internuclear distance is 2.33 Å and the Cl...Cl internuclear distance is 3.80 Å. The ratio of intenuclear distances r(Me-Cl)/r(Cl...Cl) is 1.630 and this value agrees well with the value for the regular tetrahedron model (1.633).[10]

Reactivity

editThe compound hydrolyzes, evolving hydrogen chloride:

- HfCl4 + H2O → HfOCl2 + 2 HCl

Aged samples thus often are contaminated with oxychlorides, which are also colourless.

THF forms a monomeric 2:1 complex:[14]

- HfCl4 + 2 OC4H8 → HfCl4(OC4H8)2

Because this complex is soluble in organic solvents, it is a useful reagent for preparing other complexes of hafnium.

HfCl4 undergoes salt metathesis with Grignard reagents. In this way, tetrabenzylhafnium can be prepared.

- 4 C6H5CH2MgCl + HfCl4 → (C6H5CH2)4Hf + 4 MgCl2

Similarly, salt metathesis with sodium cyclopentadienide gives hafnocene dichloride:

- 2 NaC5H5 + HfCl4 → (C5H5)2HfCl2 + 2 NaCl

With alcohols, alkoxides are formed.

- HfCl4 + 4 ROH → Hf(OR)4 + 4 HCl

These compounds adopt complicated structures.

Reduction

editReduction of HfCl4 is especially difficult. In the presence of phosphine ligands, reduction can be effected with potassium-sodium alloy:[15]

- 2 HfCl4 + 2 K + 4 P(C2H5)3 → Hf2Cl6[P(C2H5)3]4 + 2 KCl

The deep green dihafnium product is diamagnetic. X-ray crystallography shows that the complex adopts an edge-shared bioctahedral structure, very similar to the Zr analogue.

Uses

editHafnium tetrachloride is the precursor to highly active catalysts for the Ziegler-Natta polymerization of alkenes, especially propylene.[16] Typical catalysts are derived from tetrabenzylhafnium.

HfCl4 is an effective Lewis acid for various applications in organic synthesis. For example, ferrocene is alkylated with allyldimethylchlorosilane more efficiently using hafnium chloride relative to aluminium trichloride. The greater size of Hf may diminish HfCl4's tendency to complex to ferrocene.[17]

HfCl4 increases the rate and control of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions.[18] It was found to yield better results than other Lewis acids when used with aryl and aliphatic aldoximes, allowing specific exo-isomer formation.

Microelectronics applications

editHfCl4 was considered as a precursor for chemical vapor deposition and atomic layer deposition of hafnium dioxide and hafnium silicate, used as high-k dielectrics in manufacture of modern high-density integrated circuits.[19] However, due to its relatively low volatility and corrosive byproducts (namely, HCl), HfCl4 was phased out by metal-organic precursors, such as tetrakis ethylmethylamino hafnium (TEMAH).[20]

References

edit- ^ a b Niewa R., Jacobs H. (1995) Z. Kristallogr. 210: 687

- ^ Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.66. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ "Hafnium compounds (as Hf)". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Vol. 11 (4th ed.). 1991.

- ^ Hummers, W. S.; Tyree, Jr., S. Y.; Yolles, S. (1953). Zirconium and Hafnium Tetrachlorides. Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 4. p. 121. doi:10.1002/9780470132357.ch41. ISBN 9780470132357.

- ^ Hopkins, B. S. (1939). "13 Hafnium". Chapters in the chemistry of less familiar elements. Stipes Publishing. p. 7.

- ^ Hála, Jiri (1989). Halides, oxyhalides and salts of halogen complexes of titanium, zirconium, hafnium, vanadium, niobium and tantalum. Vol. 40 (1st ed.). Oxford: Pergamon. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0080362397.

- ^ Elinson, S. V. and Petrov, K. I. (1969) Analytical Chemistry of the Elements: Zirconium and Hafnium. 11.

- ^ a b Newnham, Ivan Edgar "Purification of Hafnium Tetrachloride". U.S. patent 2,961,293 November 22, 1960.

- ^ a b Spiridonov, V. P.; Akishin, P. A.; Tsirel'Nikov, V. I. (1962). "Electronographic investigation of the structure of zirconium and hafnium tetrachloride molecules in the gas phase". Journal of Structural Chemistry. 3 (3): 311. doi:10.1007/BF01151485. S2CID 94835858.

- ^ Palko, A. A.; Ryon, A. D.; Kuhn, D. W. (1958). "The Vapor Pressures of Zirconium Tetrachloride and Hafnium Tetrachloride". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 62 (3): 319. doi:10.1021/j150561a017. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086446302.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 964–966. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Duraj, S. A.; Towns; Baker; Schupp, J. (1990). "Structure of cis-Tetrachlorobis(tetrahydrofuran)hafnium(IV)". Acta Crystallographica. C46 (5): 890–2. doi:10.1107/S010827018901382X.

- ^ Manzer, L. E. (1982). "Tetrahydrofuran Complexes of Selected Early Transition Metals". Inorg. Synth. 21: 135–140. doi:10.1002/9780470132524.ch31. ISBN 978-0-470-13252-4.

- ^ Riehl, M. E.; Wilson, S. R.; Girolami, G. S. (1993). "Synthesis, X-ray Crystal Structure, and Phosphine-Exchange Reactions of the Hafnium(III)-Hafnium(III) Dimer Hf2Cl6[P(C2H5)3]4". Inorg. Chem. 32 (2): 218–222. doi:10.1021/ic00054a017.

- ^ Ron Dagani (2003-04-07). "Combinatorial Materials: Finding Catalysts Faster". Chemical and Engineering News. p. 10.

- ^ Ahn, S.; Song, Y. S.; Yoo, B. R.; Jung, I. N. (2000). "Lewis Acid-Catalyzed Friedel−Crafts Alkylation of Ferrocene with Allylchlorosilanes". Organometallics. 19 (14): 2777. doi:10.1021/om0000865.

- ^ Graham, A. B.; Grigg, R.; Dunn, P. J.; Higginson, P. (2000). "Tandem 1,3-azaprotiocyclotransfer–cycloaddition reactions between aldoximes and divinyl ketone. Remarkable rate enhancement and control of cycloaddition regiochemistry by hafnium(iv) chloride". Chemical Communications (20): 2035–2036. doi:10.1039/b005389i.

- ^ Choi, J. H.; Mao, Y.; Chang, J. P. (2011). "Development of hafnium based high-k materials—A review". Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 72 (6): 97. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2010.12.001.

- ^ Robertson, John (2006). "High dielectric constant gate oxides for metal oxide Si transistors". Reports on Progress in Physics. 69 (2): 327–396. Bibcode:2006RPPh...69..327R. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/69/2/R02. S2CID 122044323.