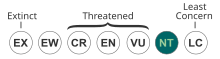

Guaiacum sanctum, commonly known as holywood, lignum vitae[4] or holywood lignum-vitae, is a species of flowering plant in the creosote bush family, Zygophyllaceae. It is native to the Neotropical realm, from Mexico through Central America, Florida in the United States, the Caribbean, and northern South America.[5] It has been introduced to other tropical areas of the world. It is currently threatened by habitat loss in its native region, and as such, is currently rated near threatened on the IUCN Red List. Guaiacum sanctum is the national tree of the Bahamas.[6]

| Guaiacum sanctum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fruiting tree at the Society of the Four Arts, Florida | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Zygophyllales |

| Family: | Zygophyllaceae |

| Genus: | Guaiacum |

| Species: | G. sanctum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Guaiacum sanctum | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

Etymology

editThe native Taíno of the Caribbean referred to the tree as guayacán.[7] The common English name is a direct translation of the Spanish "palo santo" (not to be confused with Bursera graveolens). Francisco López de Gómara as well as Oviedo make reference to the specific species as such in their respective histories of the New World. It earned its name during the time of the Spanish conquest of the New World for its use treating syphilis, whose effects recalled the "evil" of the Black Death. Its scientific name is a Latinization of the Taíno guayacán as well as the word sanctum, meaning holy.

Properties

editThis small tree is slow-growing, reaching about 7 m (23 ft) in height with a trunk diameter of 50 cm (20 in). The tree is essentially evergreen throughout most of its native range. It is shade-tolerant. It fruits between the age of 30 and 70 years over the summer months in the Northern Hemisphere.[3]

The wood is hard, heavy and self-lubricating, and has a Janka Hardness Score of 4500,[8] which is one of the hardest in the world. It can sink when placed in water.[9] There are fine ripple marks on the wood.[10]

Leaves

editThe leaves are compound, 2.5–3 cm (0.98–1.18 in) in length, and 2 cm (0.79 in) wide. They are dark green in color and occur as three to five pairs of leaflets.[4] They fold together during the hottest parts of the day.[11]

Flower

editThe purplish blue flowers have five petals each. They can grow individually or in clusters at the ends of branches.[11] The flowers have both male and female parts (stamens and pistils) and yield yellow pods containing black seeds encapsulated separately in a red skin.[12]

Uses

editThis tree is one of two species that yield the valuable lignum vitae wood, the other being Guaiacum officinale.

The wood has been used for making specific parts of ships that needed to be self-lubricating so that they would last longer.

The tree is considered to have medicinal value, used mostly for home remedies. The naturalist William Turner noted in 1568 that the plant was already being grown in India, Tamraparni (ancient Sri Lanka), Java and the Tivu islets of the ocean, and whose broth cured several harsh diseases, including French pox (syphilis).[13][14] The bark can be steeped to create tonics.[6] It is also used as an ornamental plant.[4]

Threats

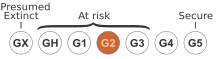

editThe type of rainforest (tropical-deciduous and dry forests) that holywood is found in are the most threatened ecosystems in the world.[3] The IUCN Red List considers the species Near Threatened, while NatureServe considers the Florida population (which is limited to the Florida Keys and Miami-Dade County) to be Critically Imperiled.[2] It is possibly extirpated from El Salvador.

The plant was exploited until it was endangered due to use for timber and medical resin. Deforestation also occurred to create more human-managed areas like farmland, cities, etc.[3] This has caused habitat fragmentation for the species, which reduces the chances of lowering its risk status.[15] Moreover, since this is a slow-growing tree, it becomes harder to regrow and maintain sizable forests of it. It can be cultivated to grow faster, but needs to be watered regularly and to have well-drained soil.[12]

It has no major pests[12] and though there were cases of illegal trade in 2008, this is no longer a major threat to the species.[3]

References

edit- ^ Rivers, M.C. (2017). "Guaiacum sanctum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T32955A68085952. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T32955A68085952.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Guaiacum sanctum. NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Guaiacum sanctum". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ a b c "Guaiacum sanctum - Plant Finder". www.missouribotanicalgarden.org. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ U.S. National Plant Germplasm System

- ^ a b "National Symbols of the Bahamas". Bahamas Facts and Figures. TheBahamasGuide. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ^ Dr. Coll Y Toste, Cayetano (1972). Diccionario Indígena (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Barcelona, Spain: Real Academia de la Historia.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Friedrich, K; Akpan, E; Wetzel, B (16 May 2017). "Structure and mechanical/abrasive wear behavior of a purely natural composite: black-fiber palm wood". Journal of Materials Science. 52 (17): 10217–10229. Bibcode:2017JMatS..5210217F. doi:10.1007/s10853-017-1184-5. S2CID 136327944.

- ^ "Guaiacum sanctum". Nature's Notebook. National Phenology Network. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ^ Record, Samuel J. “Tier-Like Arrangement of the Elements of Certain Woods.” Science, vol. 35, no. 889, 1912, pp. 75–77. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1638125.

- ^ a b "Holywood lignum vitae (Guaiacum sanctum)". Wildscreen Arkive. Wildscreem. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Stubbins, Mark (1999). Flowering Trees of Florida. Florida, USA: Pineapple Press. pp. 78–81.

- ^ Turner, William (1995). William Turner: A New Herball: Parts II and III. Cambridge University Press. p. 670. ISBN 9780521445498. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Munger, Robert S. "Guaiacum, the Holy Wood from the New World". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 4, no. 2, 1949, pp. 196–229. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24619141.

- ^ Eric J. Fuchs, James L. Hamrick; Genetic Diversity in the Endangered Tropical Tree, Guaiacum sanctum (Zygophyllaceae), Journal of Heredity, Volume 101, Issue 3, 1 May 2010, Pages 284–291, doi:10.1093/jhered/esp127

External links

edit- Media related to Guaiacum sanctum at Wikimedia Commons

- Data related to Guaiacum sanctum at Wikispecies