The grey-crowned Central American squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedii citrinellus) is a subspecies of the Central American squirrel monkey. Its range is restricted to the Pacific coast of central Costa Rica. The northern end of its range is the Rio Tulin and the southern end of its range is the Rio Grande de Terraba. South of the Rio Grande de Terraba, it is replaced by the black-crowned Central American squirrel monkey, S. oerstedii oerstedii. Populations are very fragmented, and the subspecies does not occur in all locations within its general range. It is the subspecies of Central American squirrel monkey seen in Manuel Antonio National Park in Costa Rica.[4][5]

| Grey-crowned Central American squirrel monkey[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cebidae |

| Genus: | Saimiri |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | S. o. citrinellus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Saimiri oerstedii citrinellus | |

| S. o. citrinellus range shown in red | |

The grey-crowned Central American squirrel monkey is orange or reddish-orange in color, with a black cap. It differs from the black-crowned Central American squirrel monkey in that the limbs and underparts of the grey-crowned Central American squirrel monkey are less yellowish. Some authorities also consider the cap on the grey-crowned Central American squirrel monkey to be less black than that of the black-crowned Central American squirrel monkey, but other authorities regard this as a feature that varies by age rather than by subspecies.[4]

Adults reach a length of between 266 and 291 millimetres (10.5 and 11.5 in), excluding tail, and a weight between 600 and 950 grams (21 and 34 oz).[6][7] The tail is longer than the body, and between 362 and 389 mm (14.3 and 15.3 in) in length.[6] Males have an average body weight of 829 g (29.2 oz) and females have an average body weight of 695 g (24.5 oz).[7]

The grey-crowned Central American squirrel monkey is arboreal and diurnal. It lives in groups containing several adult males, several adult females and juveniles. It is omnivorous, with a diet that includes insects and insect larvae (especially grasshoppers and caterpillars), spiders, fruit, leaves, bark, flowers and nectar. It also eats small vertebrates, including bats, birds, lizards and frogs. It finds its food foraging through the lower and middle levels of the forest.[6][8]

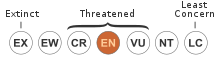

The grey-crowned Central American squirrel monkey was assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as Endangered. This was an improvement from prior assessments, in which the subspecies was assessed as "critically endangered". It is listed as endangered to a small and severely fragmented range amounting to only about 3,500 square kilometers (1,400 sq mi), and continuing habitat loss.[2] There are conservation efforts within Costa Rica to try to preserve this monkey from extinction.[9]

References

edit- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Solano-Rojas, D.; Mittermeier, R.A. (2020). "Saimiri oerstedii ssp. citrinellus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T19841A17982683. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T19841A17982683.en.

- ^ Thomas, Oldfield (1904). "New forms of Saimiri, Saccopteryx, Balantiopteryx, and Thrichomys from the Neotropical region". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Ser. 7. 13 (76): 250–251. doi:10.1080/00222930409487064.

- ^ a b Rylands, A.; Groves, C.; Mittenmeier, R.; Cortes-Ortiz, L.; Hines, J. (2006). "Taxonomy and Distributions of Mesoamerican Primates". In Estrada, A.; Garber, P.A.; Pavelka, M.S.M.; Luecke, L. (eds.). New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6.

- ^ Sierra, C.; Jimenez, I.; Altrichter, M.; Fernandez, M.; Gomez, G.; Gonzalez, J.; Hernandez, C. Herrera; H., Jimenez; B., Lopez-Arevalo; H., Millan; J., Mora, G. & Tabilo, E. (June 2003). "New Data on the Distribution and Abundance of Saimiri oerstedii citrinellus" (PDF). Primate Conservation (19): 5–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Emmons, L. (1997). Neotropical Rainforest Mammals A Field Guide (Second ed.). Chicago, Ill. ;London: Univ. of Chicago Pr. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-226-20721-8.

- ^ a b Jack, K. (2007). "The Cebines". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, A.; MacKinnon, K.; Panger, M.; Bearder, S. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 107–120. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- ^ Wainwright, M. (2002). The Natural History of Costa Rican Mammals. Miami, FL: Zona Tropical. pp. 131–134. ISBN 0-9705678-1-2.

- ^ "Save the Mono Titi Manuel Antonio Costa Rica". Retrieved 14 December 2008.