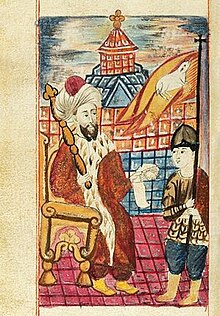

Grigor Magistros (Armenian: Գրիգոր Մագիստրոս; "Gregory the magistros"; ca. 990–1058) was an Armenian prince, linguist, scholar and public functionary. A layman of the princely Pahlavuni family that claimed descent from the dynasty established by St. Gregory the Illuminator, he was the son of the military commander Vasak Pahlavuni. After the Byzantine Empire annexed the Kingdom of Ani, Gregory went on to serve as the governor (doux) of the province of Edessa. During his tenure he worked actively to suppress the Tondrakians, a breakaway Christian Armenian sect that the Armenian and Byzantine Churches both labeled heretics.[1] He studied both ecclesiastical and secular literature, Syriac as well as Greek. He collected all Armenian manuscripts of scientific or philosophical value that were to be found, including the works of Anania Shirakatsi, and translations from Callimachus, Andronicus of Rhodes and Olympiodorus. He translated several works of Plato — The Laws, the Eulogy of Socrates, Euthyphro, Timaeus and Phaedo. Many ecclesiastics of the period were his pupils.

Works

editForemost among his writings are the "Letters," which are 80 in number, and which provide information about the political and religious problems of the time. His poetry bears the impress of both Homeric Greek and the Arabic of his own century. His chief poetical work is a long metrical narrative of the principal events recorded in the Bible. This work was purportedly written in three days in 1045 at the request of a Muslim scholar, who, after reading it, converted to Christianity. Grigor was almost the first poet to introduce the use of rhyme into Armenian prosody from Arabic poetry.[2]

Grigor II Vkayaser, a son of Grigor Magistros, was the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church between 1066 and 1105. Like his father, he was also a scholar and author; his name Vkayaser ("Lover of martyrs") refers to his work compiling and editing the lives of Armenian martyrs. [3]

Selected Publications

edit- (in Armenian) Grigor Magistrosi tghtere [The letters of Grigor Magistros]. Aleksandropol: Georg Sanoeants', 1910. An English translation, with commentary, by Professor Theo van Lint at Oxford was underway as of 2015.[4]

Further reading

edit- Muradyan, Gohar, "Greek Authors and Subject Matters in the Letters of Grigor Magistros," Revue des Études Arméniennes 35 (2013): pp. 29–77.

Notes

edit- ^ See (in Armenian) Babken Arakelyan (1976), "Sotsialakan sharzhumnere Hayastanum IX-XI darerum," [Social movements in Armenia, 9th-11th centuries] in Hay Zhoghovrdi Patmutyun [History of the Armenian People], eds. Tsatur Aghayan et al. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, vol. 3, pp. 284-88.

- ^ Hacikyan, Agop; Gabriel Basmajian; Edward S. Franchuk (2002). Nourhan Ouzounian (ed.). The Heritage of Armenian Literature Volume II: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 325–26. ISBN 0-8143-2815-6.

- ^ Thomas F. Mathews with Theo Maarten van Lint, "The Kars-Tsamandos Group of Armenian Illuminated Manuscripts of the 11th Century," in Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger and Falko Daim, (eds.), Der Doppeladler. Byzanz und die Seldschuken in Anatolien vom späten 11. bis zum 13. Jahrhundert (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, 2014), pp. 85-96.

- ^ Professor Theo M. van Lint Archived 2015-08-10 at the Wayback Machine. Faculty of Oriental Studies, Oxford.