Salamis (Greek: Σαλαμίς) was a partially constructed capital ship, referred to as either a dreadnought battleship or battlecruiser, that was ordered for the Greek Navy from the AG Vulcan shipyard in Hamburg, Germany, in 1912. She was ordered as part of a Greek naval rearmament program meant to modernize the fleet, in response to Ottoman naval expansion after the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. Salamis and several other battleships—none of which were delivered to either navy—represented the culmination of a naval arms race between the two countries that had significant effects on the First Balkan War and World War I.

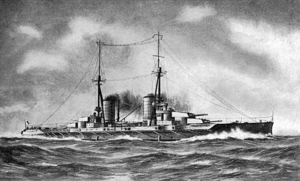

Artist's impression of Salamis if she had been taken over by the Imperial German Navy and completed during World War I

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Salamis |

| Namesake | Battle of Salamis |

| Ordered | 1912 |

| Builder | AG Vulcan, Hamburg |

| Laid down | 23 July 1913 |

| Launched | 11 November 1914 |

| Fate | Scrapped, 1932 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 19,500 long tons (19,800 t) |

| Length | 569 ft 11 in (173.71 m) |

| Beam | 81 ft (25 m) |

| Draft | 25 ft (7.6 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

The design for Salamis was revised several times during the construction process, in part due to Ottoman acquisitions. Early drafts of the vessel called for a displacement of 13,500 long tons (13,700 t), with an armament of six 14-inch (356 mm) guns in three twin-gun turrets. The final version of the design was significantly larger, at 19,500 long tons (19,800 t), with an armament of eight 14-inch guns in four turrets. The ship was to have had a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph), higher than that of other battleships of the period.

Work began on the keel on 23 July 1913, and the hull was launched on 11 November 1914. Construction stopped in December 1914, following the outbreak of World War I in July. The German navy employed the unfinished ship as a floating barracks in Kiel. The armament for this ship was ordered from Bethlehem Steel in the United States and could not be delivered due to the British blockade of Germany. Bethlehem sold the guns to Britain instead and they were used to arm the four Abercrombie-class monitors. The hull of the ship remained intact after the war and became the subject of a protracted legal dispute. Salamis was finally awarded to the builders and the hull was scrapped in 1932.

Development

editFollowing the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, during which the Ottoman fleet had proved incapable of challenging Greece's navy for control of the Aegean Sea, the Ottomans began a naval expansion program, initially rebuilding several old ironclad warships into more modern vessels.[1] In response, the Greek government decided in 1905 to rebuild its fleet, which at that time was centered on the three Hydra-class ironclads of 1880s vintage. Beginning in 1908, the Greek Navy sought design proposals from foreign shipyards. Tenders from Vickers, of Britain, for small, 8,000-long-ton (8,100 t) battleships were not taken up.[2]

In 1911, a constitutional change in Greece allowed the government to hire naval experts from other countries, which led to the invitation of a British naval mission to advise the navy on its rearmament program. The British officers recommended a program of two 12,000 long tons (12,000 t) battleships and a large armored cruiser; offers from Vickers and Armstrong-Whitworth were submitted for the proposed battleships. The Vickers design was for a smaller ship armed with nine 10-inch (254 mm) guns, while Armstrong-Whitworth proposed a larger ship armed with 14-inch (356 mm) guns. The Greek government did not pursue these proposals. Later in the year, Vickers issued several proposals for smaller vessels like those it had designed in 1908.[3]

The initial step in the Greek rearmament program was completed with the purchase of the Italian-built armored cruiser Georgios Averof in October 1909.[4] The Ottomans, in turn, purchased two German pre-dreadnought battleships, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and Weissenburg,[A] amplifying the naval arms race between the two countries.[6] The Greek Navy attempted to buy two older French battleships, and when that purchase failed to materialize, they tried unsuccessfully to buy a pair of British battleships. They then tried to buy ships from the United States, but were rebuffed due to concerns that such a sale would alienate the Ottomans, with whom the Americans had significant industrial and commercial interests.[7] The Ottomans ordered the dreadnought Reşadiye in August 1911, threatening Greek control of the Aegean. The Greeks were faced with a choice of conceding the arms race, or ordering new capital ships of their own.[8]

Rear Admiral Lionel Grant Tufnell, the head of a British naval mission to Greece, advocated purchasing another armored cruiser like Georgios Averof, along with several smaller vessels, and allocating funds to modernizing the Greek naval base at Salamis; this proposal was supported by Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, who sought to control naval spending in the tight Greek budget projected for 1912. The plan came to nothing, as the Greek government waited for the arrival of British advisers for the Salamis project.[9] In early 1912, the Greek Navy convened a committee that would be in charge of acquiring a new capital ship to counter Reşadiye, initially conceived as a battlecruiser. The new ship would be limited to a displacement of 13,000 long tons (13,000 t), since that was the largest vessel the floating dry dock in Piraeus could accommodate. The program was finalized in March, and along with the new battlecruiser, the Greeks invited tenders for destroyers, torpedo boats, submarines, and a depot ship to support them.[10]

Ten British, four French, three German, three American, one Austrian, and two Italian shipyards all submitted proposals for these contracts,[10] with Britain's Vickers and Armstrong-Whitworth submitting the same designs proposed in 1911.[11] Tufnell was part of the committee overseeing the process, but found that the Greeks strongly opposed the British designs. Vickers eventually withdrew from the competition, and the cost of Armstrong's proposal was higher than other proposals. Still, the British had hopes of obtaining the contract due to the relationship between the Greek and British navies, reflected by the number of British officers that had been seconded to the Greek Navy in recent years. French yards, on the other hand, complained that the British were unfairly benefiting from the presence of their naval mission.[12] During the competition, the Greek Navy decided that Vickers' hull design was best, but American guns, ammunition, and armor were superior to any of the British designs.[13] In the end, neither got the contracts, as negotiations between Venizelos and the German Minister to Greece eventually secured the contracts for Germany.[14][B]

In June 1912, the Greek Navy selected tenders from Germany's AG Vulcan for two destroyers and six torpedo boats, to be completed in just three to four months. This exceptionally short timeframe was accomplished through the help of the German Navy, which allowed the Greeks to take over German ships then being constructed. The contract price was evidently low, as one British firm complained that they could not understand how Vulcan would make a profit. Then, one month later, the Greeks selected Vulcan again for the construction of their battlecruiser, with its armor and armament coming from Bethlehem Steel in the United States. British firms were furious, again alleging that it would be impossible for Vulcan to make a profit on the contract, and surmising that the German government was subsidizing the purchase to get a foothold in the shipbuilding market. The Greeks, for their part, countered that the British manufacturers were colluding to keep armor plate prices high, and so they were able to significantly decrease their costs by ordering the ship's armor in the United States.[15]

Design

editThe initial design called for a ship 458 ft (140 m) long with a beam of 72 ft (22 m), a draft of 24 ft (7.3 m), and a displacement of 13,500 long tons (13,700 t). The ship was designed with 2-shaft turbines rated at 26,000 shp for a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The armament was to be six 14-inch (356 mm) guns in twin turrets all on the centerline with one amidships, eight 6 in (152 mm), eight 3 in (76 mm), and four 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, and two 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes.[16]

The design was revised several times. In mid-1912, as tensions were developing that led to the First Balkan War, the Greek Navy began serious efforts to increase its strength. In August, they were seeking only minor alterations in the ship design, but early naval operations during the war convinced the naval command of the advantages a larger ship would provide.[17] Tufnell suggested a different reason for the design changes, accusing the Germans of offering a cheap but unseaworthy design, obtaining the contract, then making a push for a more expensive but also more practical design.[18]

Hovering over all of these was the possibility that the dreadnoughts of the South American dreadnought race could be put up for sale, a prospect both countries pursued. Two, from Brazil, were already completed, and a third was under construction in Britain. Another two, for Argentina, were being built in the United States. Naval historian Paul G. Halpern wrote of this situation that "the sudden acquisition by a single power of all or even some of these ships might have been enough to tip a delicate balance of power such as that which prevailed in the Mediterranean." Both the Greeks and Ottomans were reportedly interested in the Argentine ships,[19] and Venizelos attempted to buy one of the Rivadavia-class battleships then being built in the United States for the Argentine Navy as an alternative to redesigning Salamis, in the process delaying her completion.[20]

When the Argentine government refused to sell the ship, he agreed to redesigning Salamis, and a committee that included Greek and British naval officers was created to revise the design. The committee favored a 16,500 long tons (16,800 t) design, but Hubert Searle Cardale, the only member of the British mission drawn from the Royal Navy's active list, proposed an increase to 19,500 long tons (19,800 t), since the increase would allow for a substantially more powerful vessel.[17] Venizelos initially approved an increase in displacement to 16,500 LT, but he opposed any further increases. The Foreign Minister, Lambros Koromilas, and the Speaker of the Parliament, Nikolaos Stratos, conspired to have the larger proposal adopted while Venizelos was attending the peace conference that resulted in the Treaty of London. Koromilas and Stratos misrepresented Venizelos' position to the rest of the cabinet and secured their approval for the new contract.[20]

Koromilas' and Stratos' deception proved effective, and the enlarged proposal was adopted on 23 December 1912. The most significant changes were a 50% increase in displacement, the addition of a fourth twin-gun turret, and the arrangement of the main battery in superfiring pairs. The ship was to be delivered to the Greek Navy by March 1915, at a cost of £1,693,000.[16] M. K. Barnett, writing for Scientific American, remarked that the ship would "not mark any particular advance in warship design, being, rather, an effort to combine the greatest defensive and offensive qualities with the least cost."[21] The Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers, however, believed that the ship was designed for speed and firepower at the expensive of heavy defensive armor.[22] Upon his return, Venizelos attempted to have the new contract cancelled, but Vulcan refused, noting that "Prime Ministers rise and fall from power and the influence of Venizelos will not be enduring."[20] The order for Salamis, which has been referred to alternatively as a battleship or battlecruiser, made Greece the fourteenth and final country to order a dreadnought-type ship.[17][23]

The modifications to the design came over the objections of the British, including Prince Louis of Battenberg and the new head of the British naval mission in Greece, Rear Admiral Mark Kerr. Battenberg wrote that a Greek purchase of modern capital ships would be "undesirable from every point of view", as the country's finances could not support them and the increasing power of torpedoes were making smaller ships more dangerous. Along much the same lines, Kerr suggested to Venizelos that a fleet built around smaller warships would be better suited for the constricted Aegean Sea. Strongly opposing these views were the Greek Navy and King Constantine I of Greece, both of whom desired a regular battle fleet, as they believed that it was the only way of assuring Greek naval superiority over the Ottomans.[24]

General characteristics

editSalamis was 569 feet 11 inches (173.71 m) long at the waterline with a full flush deck, and had a beam of 81 ft (25 m) and a draft of 25 ft (7.6 m). The ship was designed to displace 19,500 long tons (19,800 t). She would have been fitted with two tripod masts. Had the battleship been completed, she was to have been powered by three AEG steam turbines, each of which drove a propeller shaft. The turbines were supplied with steam by eighteen coal-fired Yarrow boilers. The boilers would have been ducted into two widely spaced funnels. This would have provided Salamis with 40,000 shaft horsepower (30,000 kW) and a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph).[16] This speed was significantly faster than the top speed of most contemporary battleships, 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph),[25] which contributed to her classification as a battlecruiser. A large crane was to be installed between the funnels to handle the ship's boats.[16]

Armament

editThe primary armament of the ship was to be eight 14 in (356 mm) /45 caliber guns mounted in four twin-gun turrets, all of which were built by Bethlehem Steel. Two turrets were to be mounted in a superfiring arrangement forward of the main superstructure, with the other two mounted similarly aft of the funnels.[16] These guns were capable of firing 1,400 lb (640 kg) armor-piercing or high-explosive shells. The shells were fired at a muzzle velocity of 2,570 feet per second (780 m/s). The guns proved to be highly resistant to wear in British service, though they suffered from significant barrel droop after around 250 shells had been fired through them, which contributed to poor accuracy after extended use. The turrets that housed the guns allowed for depression to −5° and elevation to 15°, and they were electrically operated.[26]

There is some disagreement over the nature of the ship's intended secondary battery. According to Gardiner and Gray, the battery was to consist of twelve 6 in (152 mm) /50 caliber guns, also manufactured by Bethlehem, mounted in casemates amidships, six on either side.[16] These guns fired 105-pound (48 kg) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,800 f/s (853 m/s).[27] According to Norman Friedman, these twelve guns were sold to Britain after the war broke out, where they were used to fortify the Grand Fleet's main base at Scapa Flow.[28] But Antony Preston disagrees, stating that the guns were to have been 5.5 in (140 mm) guns ordered from the Coventry Ordnance Works.[29] Salamis's armament was rounded out by twelve 75 mm (3.0 in) quick-firing guns, also mounted in casemates, and five 50 cm (20 in) submerged torpedo tubes.[16]

Armor

editSalamis had an armored belt that was 9.875 in (250.8 mm) thick in the central section of the ship, where it protected critical areas, such as the ammunition magazines and machinery spaces. On either end of the ship, past the main battery gun turrets, the belt was decreased to 3.875 in (98.4 mm) thick; the height of the belt was also decreased in these areas. The main armored deck was 2.875 in (73.0 mm) in the central portion of the ship, and as with the belt armor, in less important areas the thickness was decreased to 1.5 in (38 mm). The main battery gun turrets were protected by 9.875-inch armor plate on the sides and face, and the barbettes in which they were placed were protected by the same thickness of armor. The conning tower was lightly armored, with only 1.25 in (32 mm) worth of protection.[16]

Construction and cancellation

editThe keel for Salamis was laid down on 23 July 1913.[16] The naval balance of power in the Aegean, however, was soon to change. The Brazilian Navy put their third dreadnought (Rio de Janeiro) up for sale in October 1913, and they found no shortage of countries interested in acquiring it, including Russia, Italy, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire. The British and French were also highly involved, given their interests in the Mediterranean; in November, the French agreed to back Greece with a large loan as a way of preventing Italy from acquiring the ship. Moreover, the Greek consul general in Britain claimed that the Bank of England was prepared to advance all the money needed to purchase the ship as soon as a French loan was guaranteed. Arrangements for all this took quite some time, however, and at the end of December, the Ottomans were able to secure Rio de Janeiro with a private loan from a French bank.[30][31]

The purchase caused a panic in Greece, as the balance of naval power would shift to the Ottomans in the near future. The Greek government pressed AG Vulcan to finish Salamis as quickly as possible, but she could not be completed before mid-1915, by which time both of the new Ottoman battleships would have been delivered. The Greeks ordered two dreadnoughts from French yards, slightly modified versions of the French Bretagne-class battleship;[32] the first, Vasilefs Konstantinos, was laid down on 12 June 1914.[16] As a stopgap measure, they purchased a pair of pre-dreadnought battleships from the United States: Mississippi and Idaho, which became Kilkis and Lemnos, respectively.[33] Kerr criticized this purchase as "penny-wise and pound-foolish" for ships that were "entirely useless for war", carrying a price that could have paid for a brand-new dreadnought.[34]

The outbreak of World War I in July 1914 drastically altered the situation; the British Government declared a naval blockade of Germany in August after it entered the war. The blockade meant that the guns could not be delivered, but the ship was nevertheless launched on 11 November 1914. With no possibility of arming the ship, work was halted on 31 December 1914.[16][35] In addition, manpower shortages created by the war, along with the redirection of steel production to the needs of the Army, meant that less critical projects could not be completed, especially since other warships were nearing completion and could be finished much more quickly.[36] By this time Greece had paid AG Vulcan only £450,000. Bethlehem refused to send the main battery guns to Greece. The 14-inch guns were instead sold to the British, who used them to arm the four Abercrombie-class monitors.[16][35]

The wartime activities of the ship are unclear. According to a postwar report written for the Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, the incomplete vessel was towed to Kiel, where she was used as a barracks ship.[37] The modern naval historian René Greger states that the incomplete hull never left Hamburg.[38] Some contemporary observers believed the ship had been completed for service with the German Navy, and British Admiral John Jellicoe, the commander of the Grand Fleet, received intelligence that the ship might have been in service by 1916.[39] Other observers, such as Barnett, pointed to the difficulty the German Navy would have had in rearming the ship with German guns, as Germany possessed no designs for naval guns of that caliber or mountings suitable for use aboard Salamis. He regarded the claim that she had been put into service "doubtful".[40] Barnett's assessment was correct; a substantial rebuilding of the ship's barbette structures would have been required to accommodate German guns, and since guns available for naval use were not easily available owing to the needs of the German Army, work was directed toward German vessels under construction such as the battlecruiser Hindenburg.[41] The British realized the rumor was false when the ship did not appear at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916.[39]

Regardless of the ship's wartime disposition, however, Proceedings noted in 1920 that it was "improbable" that construction would resume upon the ship.[37] Indeed, the Greek navy refused to accept the incomplete hull, and as a result AG Vulcan sued the Greek government in 1923. A lengthy arbitration ensued.[16] The Greek navy argued that the ship, which was designed in 1912, was now obsolete and that under the Treaty of Versailles it could not be armed by the German shipyard anyway. The Greeks requested that Vulcan return advance payments made before work had stopped. The dispute went before the Greco-German Mixed Arbitral Tribunal (established under Article 304 of the Treaty of Versailles), which dragged on throughout the 1920s. In 1924, a Dutch admiral was appointed by the tribunal to evaluate the Greek complaints, and he ultimately sided with Vulcan, probably in part due to Greek inquiries to Vulcan earlier that year as to the possibility of modernizing the design. Vulcan's response did not satisfy Greek requirements, so the proposal was dropped.[42]

In 1928, with the impending recommissioning of the Turkish battlecruiser Yavuz (ex-SMS Goeben), Greece considered responding positively to an offer from Vulcan to reach a compromise, one option being to complete and modernize Salamis. The cost of the ship would be absorbed by the war reparations Germany owed Greece for the years 1928 through 1930 and part of 1931. Admiral Periklis Argyropoulos, the Minister of Marine, wanted to accept the offer, pointing to a study by the General Staff that demonstrated that a modernized Salamis would be capable of defeating Yavuz owing to the heavier armor and more powerful main battery of the Greek ship. The British naval architect Eustace Tennyson d'Eyncourt issued a study in support of Argyropoulos, pointing out that Salamis would likely also be faster than Yavuz and would have a stronger anti-aircraft battery. Commander Andreas Kolialexis opposed acquiring Salamis, and he wrote a memorandum in mid-1929 to Venizelos, who was again the Prime Minister, where he argued that completing Salamis would take too long and that a fleet of torpedo-armed vessels, including submarines, would be preferable.[43]

Venizelos determined that the cost of completing Salamis would be too high, since it would preclude the acquisition of destroyers or a powerful naval air arm. Instead, the two old pre-dreadnoughts Kilkis and Lemnos would be retained for coastal defense against Yavuz. This decision was reinforced by the onset of the Great Depression that year, which weakened Greece's already limited finances.[44] On 23 April 1932 the arbitrators determined that the Greek government owed AG Vulcan £30,000, and that AG Vulcan would be awarded the hull. The ship was broken up for scrap in Bremen that year.[16] The second Greek dreadnought, Vasilefs Konstantinos, met a similar fate. As with Salamis, work on the ship was halted by the outbreak of war in July 1914, and in the aftermath the Greek government also refused to pay for the unfinished ship.[23]

Footnotes

edit- ^ The ships were renamed Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis, respectively.[5]

- ^ The navy already had a favorable opinion of German warships, having ordered several destroyers that proved to be superior to British-built vessels. Venizelos, for his part, sought the prestige that an agreement with the German Kaiser (Emperor) Wilhelm II would bring—Wilhelm II was the brother of Sophia, the wife of the Greek King Constantine I.[14]

Endnotes

edit- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 8–10

- ^ Friedman (2015), p. 157

- ^ Friedman (2015), pp. 157–158

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 385

- ^ Sondhaus, p. 218

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 16–17

- ^ Fotakis (2005), p. 24

- ^ Halpern, p. 324

- ^ Fotakis, pp. 35–36

- ^ a b Fotakis (2005), p. 36

- ^ Fotakis (2005), p. 158

- ^ Halpern, pp. 324–325

- ^ Fotakis (2005), p. 37

- ^ a b Fotakis (2005), pp. 37–38

- ^ Halpern, pp. 326–327

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Gardiner & Gray, p. 384

- ^ a b c Fotakis (2005), p. 40

- ^ Halpern, p. 327

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–332

- ^ a b c Fotakis (2005), p. 41

- ^ Barnett, p. 252

- ^ "Battleship Salamis," p. 776

- ^ a b Sondhaus, p. 220

- ^ Halpern, pp. 334–338

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, pp. 21–31, 144–149, 197–198, 303

- ^ Friedman (2011), pp. 47–48

- ^ Friedman (2011), pp. 180–181

- ^ Friedman (2011), p. 88

- ^ Preston, p. 166

- ^ Halpern, pp. 339–341

- ^ Topliss, p. 284

- ^ Hough, pp. 71–79

- ^ Hough, pp. 79, 84

- ^ Halpern, p. 352

- ^ a b Warren, p. 160

- ^ Weir, pp. 128–130

- ^ a b Underwood, p. 1501

- ^ Greger, p. 250

- ^ a b Jellicoe, p. 425

- ^ Barnett, p. 251

- ^ Anderson & Darnell, p. 170

- ^ Fotakis (2010), pp. 4–5

- ^ Fotakis (2010), pp. 21–22

- ^ Fotakis (2010), pp. 23, 26

References

edit- Anderson, R. C.; Darnell, V. C. (1945). "The Salamis". The Mariner's Mirror. 45. London: Society for Nautical Research: 169–170. OCLC 614410103.

- Barnett, M. K. (March–April 1915). "Recent German Naval Construction". Journal of the United States Artillery. 45 (2): 247–252. Bibcode:1915SciAm.113..484B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican12041915-484.

- Engineers, American Society of Naval (1913). "Battleship Salamis". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. 25 (4): 775–776. ISSN 0099-7056.

- Fotakis, E. (2010). "Greek Naval Policy and Strategy, 1923–1932" (PDF). Nausivios Chora: A Journal in Naval Sciences and Technology: 365–393. ISSN 1791-4469.

- Fotakis, Zisis (2005). Greek Naval Strategy and Policy, 1910–1919. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35014-3.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2015). The British Battleship: 1906–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781591142546.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Greger, René (1993). Battleships of the World. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-069-X.

- Halpern, Paul G (1971). The Mediterranean Naval Situation, 1908–1914. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674564626.

- Hough, Richard (1966). The Big Battleship. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 8898108.

- Jellicoe, John (1966). Patterson, A. Temple (ed.). The Jellicoe Papers: Selections from the Private and Official Correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Earl Jellicoe of Scapa. London: Navy Records Society. OCLC 925910847.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-610-1.

- Nottlemann, Dirk (2020). "From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The Development of the German Navy 1864–1918, Part XB". Warship International. LVII (1): 49–55. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations, 1914–1918. London: Arms and Armour Press. OCLC 464384648.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0.

- Topliss, David (1988). "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 1904–1914". Warship International. 25 (3): 240–89. OCLC 1647131.

- Underwood, H. W. (1920). "Professional Notes". Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. 46 (9): 1493–1539. OCLC 847977635.

- Warren, Kenneth (2007). Industrial Genius: The Working Life of Charles Michael Schwab. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4326-6.

- Weir, Gary (1992). Building the Kaiser's Navy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557509298.

- Zolandez, Thomas (2007). "Question 16/43: British 14-in Naval Guns". Warship International. XLIV (2): 153–155. ISSN 0043-0374.