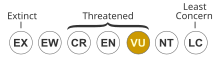

The great curassow (Crax rubra) is a large, pheasant-like bird from the Neotropical rainforests, its range extending from eastern Mexico, through Central America to western Colombia and northwestern Ecuador. Male birds are black with curly crests and yellow beaks; females come in three colour morphs, barred, rufous and black. These birds form small groups, foraging mainly on the ground for fruits and arthropods, and the occasional small vertebrate, but they roost and nest in trees. This species is monogamous, the male usually building the rather small nest of leaves in which two eggs are laid. This species is threatened by loss of habitat and hunting, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has rated its conservation status as "vulnerable".

| Great curassow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female (red morph) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Cracidae |

| Genus: | Crax |

| Species: | C. rubra

|

| Binomial name | |

| Crax rubra | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

editAt 78–100 cm (31–39 in) in length and 3.1–4.8 kg (6.8–10.6 lb) in weight, this is a very large cracid.[3][4] Females are somewhat smaller than males. It is the most massive and heavy species in the family but its length is matched by a few other cracids.[3][5][6] Three other species of curassow (the northern helmeted, the southern helmeted, and the black are all around the same average length as the great curassow. In this species, standard measurements are as follows: the wing chord is 36 to 42.4 cm (14.2 to 16.7 in), the tail is 29 to 38 cm (11 to 15 in) and the tarsus is 9.4 to 12 cm (3.7 to 4.7 in). They have the largest mean standard measurements in the family, other than tail length.[7]

The male is black with a curly crest, a white belly, and a yellow knob on its bill.[3] There are three morphs of female great curassows:[3] barred morph females with barred neck, mantle, wings and tail; rufous morph with an overall reddish brown plumage and a barred tail; and dark morph female with a blackish neck, mantle and tail (the tail often faintly vermiculated), and some barring to the wings. In most regions only one or two morphs occur, and females showing a level of intermediacy between these morphs are known (e.g. resembling rufous morph, but with black neck and faint vermiculations to the wings).

This species has a similar voice to several other curassows, its call consisting of a "peculiar" lingering whistle.[7]

Ecology

editBreeding

editA monogamous species, the male great curassow may build the nest and attract a female's attention to it, though in other cases both members of a pair will build the nest structure. Two eggs are typically laid in a relatively small nest (usually made largely of leaves), each egg measuring 9.1 cm × 6.7 cm (3.6 in × 2.6 in) and weighing 200 g (7.1 oz). The young curassow weighs 123 g (4.3 oz) upon hatching; 2,760 g (6.08 lb) as a half-year-old immature fledgling; and by a year of age, when fully fledged and independent of parental care, will be about three-quarters of their adult weight at 3,600 g (7.9 lb).

Foraging and diet

editIts diet consists mainly of fruits, figs and arthropods. Small vertebrates may supplement the diet on occasion, including small mammals (such as rodents). Unlike other cracids, such as guans, they feed largely on fallen fruit rather than pluck fruit directly from the trees. In Tamaulipas, it feeds largely on the fruit Spondias mombin. Elsewhere, it may prefer the red berries of Chione trees.[7]

Behavior and predators

editThis species has been noted for its rather aggressive temperament, which has been regularly directed at humans when the birds are held in captivity. Undoubtedly, they have this inclination in order to repel natural predators, from both themselves and their offspring. Known natural predators of this species have included ocelots and ornate hawk-eagles, though chicks and eggs likely have a broader range of predators. When a potential predator is near their offspring, curassows have been noted to engage in a distraction display, feigning injury. When attacking humans, the curassows leap in fluttering flight and scratch about the head, targeting the eyes. Their lifespan in captivity has reached at least 24 years.[7]

Evolution

editThe great curassow is the most northerly Crax species. It is part of a clade that inhabited the north of South America since about 9 mya (Tortonian, Late Miocene). As the Colombian Andes were uplifted around 6 mya, this species' ancestors were cut off from the population to their southeast. The latter would in time evolve into the blue-billed curassow. The ancestral great curassows then spread along the Pacific side of the Andes, and into Central America during the Pliocene and Pleistocene[8] as part of the Great American Interchange.

Status

editDue to ongoing habitat loss and overhunting in some areas, the great curassow is evaluated as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1] It is listed on Appendix III of CITES in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Colombia and Honduras. Of the smaller subspecies C. r. griscomi of Cozumel Island, only a few hundred remain. Its population seems either to have been slowly increasing since the 1980s, or to be fluctuating at a low level; it is vulnerable to hurricanes.[3]

This species has proven to produce fertile hybrids with its closest living relative, the blue-billed curassow, and also with the much more distantly related black curassow.[3]

In Mexico, there are Unidades de Manejo para la Conservación de la Vida Silvestre [Management Units for the Conservation of Wildlife] (UMAs) who are breeding great curassows in captivity.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2020). "Crax rubra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22678521A178001922. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22678521A178001922.en. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ del Hoyo, Josep; Kirwan, Guy M. (2020). "Great Curassow (Crax rubra)". In Del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi; Christie, David; De Juana, Eduardo (eds.). Great Curassow Crax rubra. Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. doi:10.2173/bow.grecur1.01. S2CID 242884761. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A.; Sargatal, J., eds. (1994). "Plate 33". 44. Great Curassow. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2 (New World Vultures to Guineafowl). Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. p. 359. ISBN 978-84-87334-15-3.

- ^ Arion, Frank Martinus (Summer 1998). "The Great Curassow or the Road to Caribbeanness". Callaloo. 21 (3, Caribbean Literature from Suriname, The Netherlands Antilles, Aruba, and The Netherlands: A Special Issue). Johns Hopkins University Press: 447–452. doi:10.1353/cal.1998.0127. JSTOR 3299577. S2CID 161491776.

- ^ Restall; Rodner; Lentino (2006). Birds of Northern South America. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-7243-9 (vol. 1). ISBN 0-7136-7242-0 (vol. 2).

- ^ Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia. Marshall Cavendish Corporation, Jan 1, 2002. ISBN 9780761472667.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, Nigel (2006). Curassows, Guans and Chachalacas. UK: Wildside Books. ISBN 978-0905062266.

- ^ Pereira, Sérgio Luiz; Baker, Allan J. (2004). "Vicariant speciation of curassows (Aves, Cracidae): a hypothesis based on mitochondrial DNA phylogeny". Auk (in English and Spanish). 121 (3): 682–694. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2004)121[0682:VSOCAC]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86320083.

- ^ Aguilar, Héctor F.; Rivera Guzmán, Roberto A. (2002). "Biología Reproductiva del Hocofaisan Crax rubra rubra Linnaeus 1758, Craciformes: Cracidae) en México, Análisis Químico y Estudio Morfológico de la Cáscara de Huevo" [Breeding Biology of Great Curassow, Crax Rubra Rubra Linnaeus 1758 (Craciformes: Cracidae) in Captivity in Mexico, Chemical Analysis and Morphological Study of Eggshell]. Zoocriaderos (in Spanish). 4 (2): 1–33. ISSN 0798-7811.

External links

edit- BirdLife species factsheet for Crax rubra

- Great curassow stamps[usurped] from British Honduras (now Belize), El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico at www.bird-stamps.org[usurped]

- Great curassow photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Great curassow female photo at tropicalhardwoods.com

- "Crax rubra". Avibase.

- "Great curassow media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Great curassow species account at Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Crax rubra in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr

- great-curassow/crax-rubra Great curassow media from ARKive