Government cheese is processed cheese provided to welfare beneficiaries, Food Stamp recipients, and the elderly receiving Social Security in the United States, as well as to food banks and churches. This processed cheese was used in military kitchens during World War II and has been used in schools since the 1950s.

Government cheese is a commodity cheese that was controlled by the US federal government from World War II to the early 1980s. Government cheese was created to maintain the price of dairy when dairy industry subsidies artificially increased the quantity supplied of milk and created a surplus of milk that was then converted into cheese, butter, or powdered milk. The cheese, along with the butter and dehydrated milk powder, was stored in over 150 warehouses across 35 states.[1]

History and impact

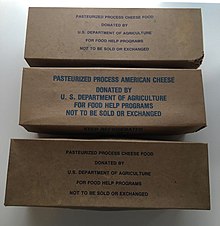

editThe cheese was bought and stored by the government's Commodity Credit Corporation. Direct distribution of dairy products began in 1982 under the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program of the Food and Nutrition Service. According to the government, it "slices and melts well."[2] The cheese was provided monthly, in unsliced block form, with generic product labeling and packaging.

The cheese was often from food surpluses stockpiled by the government as part of milk price supports. Butter was also stockpiled and then provided under the same program. Some government cheese was made of kosher products.[3] The cheese product is also distributed to victims of a natural disaster following a state of emergency declaration.

Government cheese became an important topic for the press in the 1980s, when the press learned about the milk products that were being stored across the nation while millions of Americans felt food insecurity. During the same time in the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan's administration cut the budget on the US federal food stamp program.[1]

On December 22, 1981, Reagan signed and authorized into law the finalized version of the Agriculture and Food Act of 1981, which called for five hundred and sixty million pounds (250,000 metric tons) of cheese stockpiled by the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) to be released, saying that it would ...

"…be distributed free to the needy by nonprofit organizations." Ronald Reagan, in his official statement about the distribution of the Cheese Inventory of the Commodity Credit Corporation, said, "The 1981 farm bill I signed today will slow the rise in price support levels, but even under this bill, surpluses will continue to pile up. A total of more than 560 million pounds [250,000 t] of cheese has already been consigned to warehouses, so more distributions may be necessary as we continue our drive to root out waste in government and make the best possible use of our nation's resources."[4]

As the bill stated, any state that asked for the cheese would get 30 million pounds (14,000 metric tons) of it, in 5-pound (2.3 kg) blocks. The logic behind the distribution was to remove waste effectively and to use all possible resources available in the United States. One representative from the United States Department of Agriculture remarked, "Probably the cheapest and most practical thing would be to dump it in the ocean."[5]

The bill, while initially receiving significant support from the divided Congress, just barely passed the Democratic-controlled House by a count of 205 for and 203 against. In the Senate, where Republicans had gained control following the 1980 elections, the bill passed much more easily with 68 votes for and 32 against.

Distribution

editThe distribution of government cheese was claimed to not have an adverse effect on commercially available cheeses, as the government was required to purchase dairy products like cheese to keep the commercial companies afloat. The government could then sell or give the cheese away to foreign countries. At the time of Ronald Reagan's signing of the Agriculture and Food Act of 1981, the cheese stockpile equaled more than 2 lb (1 kg) of cheese for each person living in the United States.[6] The first shipments of government cheese were frequently moldy.[1]

Those who received the cheese did not lose any food stamps and were not required to surrender food stamps for the cheese. California was the first state to take the cheese; the first delivery that it received was three million pounds (1,400 t).[1] Government cheese was provided through the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program to recipients of welfare, food stamps, and Social Security, at no cost to them. Government cheese was nominally removed in the 1990s when the dairy market stabilized.[7]

Ingredients

editGovernment cheese is "pasteurized process American cheese", a term with a standard of identity. It is produced from a variety of cheese (Cheddar cheese, Colby cheese, cheese curd, or granular cheese), made meltable using emulsifiers and blended. Other ingredients specified in the standard of identity may be used.[3]

Nutritional value and flavor

editIt has been argued that people in poverty, such as those entitled to government cheese, are more likely to become obese. Between 1988 and 1994, those individuals below the poverty line had an obesity rate of 29.2 percent.[8] The Food Security Act of 1985 (the 1985 farm bill) attempted to reduce milk production, but has been labeled as a "hodgepodge of misdirected political compromise."[9]

The nutrition facts on government cheese suggests a serving size of 1 ounce (28 g), or two slices, of cheese per serving. It also notes that the nutritional information represents the average nutritional value of "Processed American cheese" which was offered by the commodity food program. Per serving, the total fat content is 9 g, of which 6 g are saturated fat. Per serving, there are 30 mg of cholesterol and 380 mg of sodium.[2]

The flavor of government cheese has been compared as ranging from mild cheddar to Velveeta cheese due to variations in ingredients. Some people reminisce both good or bad opinions concerning the flavor of government cheese. Affinity for government cheese is correlated with low socioeconomic status; however, this correlation also overlaps with who was most likely to receive and consume it.[10][11][12][13]

21st century

editOn August 23, 2016, the US Department of Agriculture stated that it planned to purchase approximately eleven million pounds (5,000 t) of cheese,[14] worth $20 million,[15] to give aid to food banks and food pantries from across the United States,[14] to reduce a $1.2 billion[15] cheese surplus that had been at its highest level in thirty years, and to stabilize farm prices.[15] This purchase also added revenues for the dairy producers. Regarding the purchase, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said, "This commodity purchase is part of a robust, comprehensive safety net that will help reduce a cheese surplus that is at a 30-year high while, at the same time, moving a high-protein food to the tables of those most in need. USDA will continue to look for ways within its authorities to tackle food insecurity and provide for added stability in the marketplace."[15]

As of 2022, as part of the USDA Food Nutrition Service Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP), eligible seniors over the age of 60 are provided one 32-ounce (910 g) block of processed cheese food each month, supplied by participating dairies.[16] This number had not changed since 2018.[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Jones, Bradley M. (October 25, 2016). Donnelly, Catherine (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Cheese. Oxford University Press. p. 325. ISBN 9780199330898.

- ^ a b "All Purpose" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2006.

- ^ a b USDA Commodity Requirements - PCD5 Pasteurized Process American Cheese for Use in Domestic Programs Archived December 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine - description of government cheese

- ^ "Ronald Reagan: Statement About Distribution of the Cheese Inventory of the Commodity Credit Corporation". presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Fritschner, Sarah (December 17, 1981). "The Big Cheese: Storing the Surplus". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Ap (December 23, 1981). "SURPLUS CHEESE GOES TO POOR AS PRESIDENT SIGNS FARM BILL". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Shekhtman, Lonnie (2016). "Why the US Government Wants Americans to Eat More Cheese". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023.

- ^ Correll, Michael (2010). "Getting fat on government cheese: the connection between social welfare participation, gender, and obesity in America". Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy. 18: 45+.

- ^ Hamilton, Robert A. (March 23, 1986). "U.S. OFFERS DAIRYMEN A BUYOUT". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "The government cheese phenomenon and the American cheese stockpile today". CNBC. February 16, 2019. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "The Tyranny and the Comfort of Government Cheese". August 21, 2018. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "How the US Ended up with Warehouses Full of 'Government Cheese'". Archived from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "The return of government cheese, canned beef, and stigmatizing the poor". February 16, 2018. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "USDA to Purchase Surplus Cheese for Food Banks and Families in Need, Continue to Assist Dairy Producers". fsa.usda.gov. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "US to Buy Cheese to Help Milk Prices and Feed the Poor". Farmers Weekly. 1123. 2016. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022.

- ^ "COMMODITY SUPPLEMENTAL FOOD PROGRAM MAXIMUM MONTHLY DISTRIBUTION RATES" (PDF). April 19, 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Commodity Supplemental Food Program" (PDF). www.fns.usda.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018.