Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus[1][2][3] (ca. 75 BC – 12 April 45 BC)[4] was a Roman politician and general from the late Republic (1st century BC).[5][1]

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus | |

|---|---|

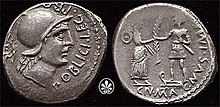

Denarius of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus the Younger, 46-45 BC | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 75 BC |

| Died | 12 April 45 BC (aged 30) Lauro, Hispania Ulterior |

| Cause of death | Killed in battle |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Relations | Pompeia gens |

| Parent(s) | Pompey Magnus and Mucia Tertia |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Pompey |

| Rank | Legatus |

| Battles/wars | |

Biography

editGnaeus Pompeius Magnus was the elder son of Pompey the Great (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus) by his third wife, Mucia Tertia.[6][1] Both he and his younger brother Sextus Pompey grew up in the shadow of their father, one of Rome's best generals and not originally a conservative politician who drifted to the more traditional faction when Julius Caesar became a threat. When Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC, thus starting a civil war, Gnaeus followed his father in their escape to the East, as did most of the conservative senators. Pompey's army lost the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, and Pompey himself had to run for his life, only to be murdered in Egypt on 29 September the same year.[5]

After the murder, Gnaeus and his brother Sextus joined the resistance against Caesar in the Africa Province.[4][7] Together with Metellus Scipio, Cato and other senators, they prepared to oppose Caesar and his army to the end.[4][7] Here however Cato chastised Gnaeus, saying his father had achieved much more at his age than Gnaeus had. This prompted Gnaeus to launch a solo attack on Mauretania however he was defeated at the Battle of Ascurum. Gnaeus fled to the Balearic Islands, where he was joined by Sextus following Caesar's defeat of Metellus Scipio and Cato, who subsequently committed suicide, at the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BC. Together with Titus Labienus, former general in Caesar's army, the Pompey brothers crossed over to Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula, comprising modern Spain and Portugal), where they raised yet another army.[7]

Caesar soon followed and, on 17 March 45 BC, the armies met in the Battle of Munda.[5] Both armies were large and led by able generals. The battle was closely fought, but eventually a cavalry charge by Caesar turned events to his side. In the battle and the panicked escape that followed, Titus Labienus and an estimated 30,000 men of the Pompeian side died. Gnaeus and Sextus managed to escape another time but supporters were difficult to find. It was by now clear Caesar had won the civil war. Within a few weeks, Gnaeus Pompeius was cornered and killed by Lucius Caesennius Lento.[5][7]

His younger brother Sextus Pompeius was able to keep one step ahead of his enemies, and survived his brother for another decade by establishing a semi-independent kingdom in Sicily with a powerful naval fleet, becoming so powerful he had to be accommodated by the Second Triumvirate until Augustus sent his general Marcus Agrippa who fought the Bellum Siculum with Sextus who was eventually defeated and executed.

Marriage

editGnaeus Pompeius married Claudia Pulcra, daughter of Appius Claudius Pulcher and sister of Marcus Junius Brutus' first wife, who survived him; they had no children.

References

edit- ^ a b c Miltner, Franz (1950). "RE: Pompey 31" (PNG). In Paly, August; Wissowa, Georg (eds.). Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (Pauly–Wissowa) (in German). Vol. XXI.2 (3rd ed.). Stuttgart, Germany. p. 2211.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1951). The Magistrates of the Roman Republic. Vol. III. Poughkeepsie, New York, United States: American Philological Association. p. 165.

- ^ Crawford, Michael Hewson (2001) [1974]. "Catalogue". Roman Republic Coinage. Vol. I (8th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 479–481. ISBN 9780521074926. LCCN 77-164450 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Julius Caesar (1959) [40 BC]. "39". De Bello Hispaniensi [On the Spanish war]. Translated by William Alexander McDevitte and W.S. Bohn. Rome, Italy – via Wikisource.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Chilver, Guy Edward Farquhar; Badian, Ernst (22 December 2015). "Pompeius Magnus (2), Gnaeus". In Goldberg, Sander; Bendlin, Andreas (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary. Roman History and Historiography (4th ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5208. ISBN 9780199381135. OCLC 949733733.

- ^ Haley, Shelley P. (1 April 1985). "The Five Wives of Pompey the Great". Greece & Rome. 32 (1). Oxford, United Kingdom: The Classical Association/Clarendon Press: 49–59. doi:10.1017/S0017383500030138. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 642299. S2CID 154822339.

- ^ a b c d Berdowski, Piotr (2012). Berdowski, Piotr; Niesiołowski-Spanò, Łukasz (eds.). "Gn. Pompeius, the son of Pompey the Great: An embarrassing ally in the African War? (48–46 BC)". Palamedes. A Journal of Ancient History. 7 (1). Warsaw, Poland: University of Warsaw/Lockwood Press: 117–142. ISSN 1896-8244.

Further reading

edit- de Méritens de Villeneuve, Guillaume (2023). Les fils de Pompée et l'opposition à César et au triumvirat: 46–35 av. J.-C. Rome: École française de Rome. ISBN 9782728316113.