Globalization (North American spelling; also Oxford spelling [UK]) or globalisation (non-Oxford British spelling; see spelling differences) is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide.[1] The term globalization first appeared in the early 20th century (supplanting an earlier French term mondialisation), developed its current meaning sometime in the second half of the 20th century, and came into popular use in the 1990s to describe the unprecedented international connectivity of the post–Cold War world.[2] Its origins can be traced back to 18th and 19th centuries due to advances in transportation and communications technology. This increase in global interactions has caused a growth in international trade and the exchange of ideas, beliefs, and culture. Globalization is primarily an economic process of interaction and integration that is associated with social and cultural aspects. However, disputes and international diplomacy are also large parts of the history of globalization, and of modern globalization.

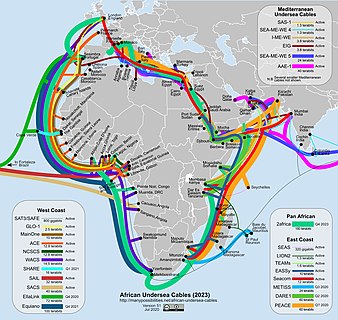

Economically, globalization involves goods, services, data, technology, and the economic resources of capital.[3] The expansion of global markets liberalizes the economic activities of the exchange of goods and funds. Removal of cross-border trade barriers has made the formation of global markets more feasible.[4] Advances in transportation, like the steam locomotive, steamship, jet engine, and container ships, and developments in telecommunication infrastructure such as the telegraph, the Internet, mobile phones, and smartphones, have been major factors in globalization and have generated further interdependence of economic and cultural activities around the globe.[5][6][7]

Though many scholars place the origins of globalization in modern times, others trace its history to long before the European Age of Discovery and voyages to the New World, and some even to the third millennium BCE.[8] Large-scale globalization began in the 1820s, and in the late 19th century and early 20th century drove a rapid expansion in the connectivity of the world's economies and cultures.[9] The term global city was subsequently popularized by sociologist Saskia Sassen in her work The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo (1991).[10]

In 2000, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) identified four basic aspects of globalization: trade and transactions, capital and investment movements, migration and movement of people, and the dissemination of knowledge.[11] Globalizing processes affect and are affected by business and work organization, economics, sociocultural resources, and the natural environment. Academic literature commonly divides globalization into three major areas: economic globalization, cultural globalization, and political globalization.[12]

Proponents of globalization point to economic growth and broader societal development as benefits, while opponents claim globalizing processes are detrimental to social well-being due to ethnocentrism, environmental consequences, and other potential drawbacks.[13][14]

Between 1990 and 2010, globalisation progressed rapidly, driven by the information and communication technology revolution that lowered communication costs, along with trade liberalisation and the shift of manufacturing operations to emerging economies (particularly China). [15][16][17]

Etymology and usage

editThe word globalization was used in the English language as early as the 1930s, but only in the context of education, and the term failed to gain traction. Over the next few decades, the term was occasionally used by other scholars and media, but it was not clearly defined.[2] One of the first usages of the term in the meaning resembling the later, was by French economist François Perroux in his essays from the early 1960s (in his French works he used the term "mondialisation" (literarly worldization in French), also translated as mundialization).[2] Theodore Levitt is often credited with popularizing the term and bringing it into the mainstream business audience in the later in the middle of 1980s.[2]

Though often treated as synonyms, in French, globalization is seen as a stage following mondialisation, a stage that implies the dissolution of national identities and the abolishment of borders inside the world network of economic exchanges.[18]

Since its inception, the concept of globalization has inspired competing definitions and interpretations. Its antecedents date back to the great movements of trade and empire across Asia and the Indian Ocean from the 15th century onward.[19][20]

In 1848, Karl Marx noticed the increasing level of national inter-dependence brought on by capitalism, and predicted the universal character of the modern world society. He states:

The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. To the great chagrin of Reactionists, it has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. . . . In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations.[21]

Sociologists Martin Albrow and Elizabeth King define globalization as "all those processes by which the people of the world are incorporated into a single world society."[3] In The Consequences of Modernity, Anthony Giddens writes: "Globalization can thus be defined as the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa."[22] In 1992, Roland Robertson, professor of sociology at the University of Aberdeen and an early writer in the field, described globalization as "the compression of the world and the intensification of the consciousness of the world as a whole."[23]

In Global Transformations, David Held and his co-writers state:

Although in its simplistic sense globalization refers to the widening, deepening and speeding up of global interconnection, such a definition begs further elaboration. ... Globalization can be on a continuum with the local, national and regional. At one end of the continuum lie social and economic relations and networks which are organized on a local and/or national basis; at the other end lie social and economic relations and networks which crystallize on the wider scale of regional and global interactions. Globalization can refer to those spatial-temporal processes of change which underpin a transformation in the organization of human affairs by linking together and expanding human activity across regions and continents. Without reference to such expansive spatial connections, there can be no clear or coherent formulation of this term. ... A satisfactory definition of globalization must capture each of these elements: extensity (stretching), intensity, velocity and impact.[24]

Held and his co-writers' definition of globalization in that same book as "transformation in the spatial organization of social relations and transactions—assessed in terms of their extensity, intensity, velocity and impact—generating transcontinental or inter-regional flows" was called "probably the most widely-cited definition" in the 2014 DHL Global Connectiveness Index.[25]

Swedish journalist Thomas Larsson, in his book The Race to the Top: The Real Story of Globalization, states that globalization:

...is the process of world shrinkage, of distances getting shorter, things moving closer. It pertains to the increasing ease with which somebody on one side of the world can interact, to mutual benefit, with somebody on the other side of the world.[26]

Paul James defines globalization with a more direct and historically contextualized emphasis:

Globalization is the extension of social relations across world-space, defining that world-space in terms of the historically variable ways that it has been practiced and socially understood through changing world-time.[27]

Manfred Steger, professor of global studies and research leader in the Global Cities Institute at RMIT University, identifies four main empirical dimensions of globalization: economic, political, cultural, and ecological. A fifth dimension—the ideological—cutting across the other four. The ideological dimension, according to Steger, is filled with a range of norms, claims, beliefs, and narratives about the phenomenon itself.[28]

James and Steger stated that the concept of globalization "emerged from the intersection of four interrelated sets of 'communities of practice' (Wenger, 1998): academics, journalists, publishers/editors, and librarians."[2]: 424 They note the term was used "in education to describe the global life of the mind"; in international relations to describe the extension of the European Common Market, and in journalism to describe how the "American Negro and his problem are taking on a global significance".[2] They have also argued that four forms of globalization can be distinguished that complement and cut across the solely empirical dimensions.[27][29] According to James, the oldest dominant form of globalization is embodied globalization, the movement of people. A second form is agency-extended globalization, the circulation of agents of different institutions, organizations, and polities, including imperial agents. Object-extended globalization, a third form, is the movement of commodities and other objects of exchange. He calls the transmission of ideas, images, knowledge, and information across world-space disembodied globalization, maintaining that it is currently the dominant form of globalization. James holds that this series of distinctions allows for an understanding of how, today, the most embodied forms of globalization such as the movement of refugees and migrants are increasingly restricted, while the most disembodied forms such as the circulation of financial instruments and codes are the most deregulated.[30]

The journalist Thomas L. Friedman popularized the term "flat world", arguing that globalized trade, outsourcing, supply-chaining, and political forces had permanently changed the world, for better and worse. He asserted that the pace of globalization was quickening and that its impact on business organization and practice would continue to grow.[31]

Economist Takis Fotopoulos defined "economic globalization" as the opening and deregulation of commodity, capital, and labor markets that led toward present neoliberal globalization. He used "political globalization" to refer to the emergence of a transnational élite and a phasing out of the nation-state. Meanwhile, he used "cultural globalization" to reference the worldwide homogenization of culture. Other of his usages included "ideological globalization", "technological globalization", and "social globalization".[32]

Lechner and Boli (2012) define globalization as more people across large distances becoming connected in more and different ways.[33]

"Globophobia" is used to refer to the fear of globalization, though it can also mean the fear of balloons.[34][35][36]

History

editThere are both distal and proximate causes which can be traced in the historical factors affecting globalization. Large-scale globalization began in the 19th century.[37]

Archaic

editArchaic globalization conventionally refers to a phase in the history of globalization including globalizing events and developments from the time of the earliest civilizations until roughly the 1600s. This term is used to describe the relationships between communities and states and how they were created by the geographical spread of ideas and social norms at both local and regional levels.[38]

In this schema, three main prerequisites are posited for globalization to occur. The first is the idea of Eastern Origins, which shows how Western states have adapted and implemented learned principles from the East.[38] Without the spread of traditional ideas from the East, Western globalization would not have emerged the way it did. The interactions of states were not on a global scale and most often were confined to Asia, North Africa, the Middle East, and certain parts of Europe.[38] With early globalization, it was difficult for states to interact with others that were not close. Eventually, technological advances allowed states to learn of others' existence and thus another phase of globalization can occur. The third has to do with inter-dependency, stability, and regularity. If a state is not dependent on another, then there is no way for either state to be mutually affected by the other. This is one of the driving forces behind global connections and trade; without either, globalization would not have emerged the way it did and states would still be dependent on their own production and resources to work. This is one of the arguments surrounding the idea of early globalization. It is argued that archaic globalization did not function in a similar manner to modern globalization because states were not as interdependent on others as they are today.[38]

Also posited is a "multi-polar" nature to archaic globalization, which involved the active participation of non-Europeans. Because it predated the Great Divergence in the nineteenth century, where Western Europe pulled ahead of the rest of the world in terms of industrial production and economic output, archaic globalization was a phenomenon that was driven not only by Europe but also by other economically developed Old World centers such as Gujarat, Bengal, coastal China, and Japan.[39]

The German historical economist and sociologist Andre Gunder Frank argues that a form of globalization began with the rise of trade links between Sumer and the Indus Valley civilization in the third millennium BCE. This archaic globalization existed during the Hellenistic Age, when commercialized urban centers enveloped the axis of Greek culture that reached from India to Spain, including Alexandria and the other Alexandrine cities. Early on, the geographic position of Greece and the necessity of importing wheat forced the Greeks to engage in maritime trade. Trade in ancient Greece was largely unrestricted: the state controlled only the supply of grain.[8]

Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in the development of civilizations from China, the Indian subcontinent, Persia, Europe, and Arabia, opening long-distance political and economic interactions between them.[40] Though silk was certainly the major trade item from China, common goods such as salt and sugar were traded as well; and religions, syncretic philosophies, and various technologies, as well as diseases, also traveled along the Silk Routes. In addition to economic trade, the Silk Road served as a means of carrying out cultural trade among the civilizations along its network.[41] The movement of people, such as refugees, artists, craftsmen, missionaries, robbers, and envoys, resulted in the exchange of religions, art, languages, and new technologies.[42] From around 3000 BCE to 1000 CE, connectivity within Afro-Eurasia was centered upon the Indo-Mediterranean region, with the Silk Road later rising in importance with the Mongol Empire's consolidation of Asia in the 13th century.[43][44]

Early modern

edit"Early modern" or "proto-globalization" covers a period of the history of globalization roughly spanning the years between 1600 and 1800. The concept of "proto-globalization" was first introduced by historians A. G. Hopkins and Christopher Bayly. The term describes the phase of increasing trade links and cultural exchange that characterized the period immediately preceding the advent of high "modern globalization" in the late 19th century.[45] This phase of globalization was characterized by the rise of maritime European empires, in the 15th and 17th centuries, first the Portuguese Empire (1415) followed by the Spanish Empire (1492), and later the Dutch and British Empires. In the 17th century, world trade developed further when chartered companies like the British East India Company (founded in 1600) and the Dutch East India Company (founded in 1602, often described as the first multinational corporation in which stock was offered) were established.[46]

An alternative view from historians Dennis Flynn and Arturo Giraldez, postulated that: globalization began with the first circumnavigation of the globe under the Magellan-Elcano expedition which preluded the rise of global silver trade.[47][48]

Early modern globalization is distinguished from modern globalization on the basis of expansionism, the method of managing global trade, and the level of information exchange. The period is marked by the shift of hegemony to Western Europe, the rise of larger-scale conflicts between powerful nations such as the Thirty Years' War, and demand for commodities, most particularly slaves. The triangular trade made it possible for Europe to take advantage of resources within the Western Hemisphere. The transfer of animal stocks, plant crops, and epidemic diseases associated with Alfred W. Crosby's concept of the Columbian exchange also played a central role in this process. European, Middle Eastern, Indian, Southeast Asian, and Chinese merchants were all involved in early modern trade and communications, particularly in the Indian Ocean region.

Modern

editAccording to economic historians Kevin H. O'Rourke, Leandro Prados de la Escosura, and Guillaume Daudin, several factors promoted globalization in the period 1815–1870:[49]

- The conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars brought in an era of relative peace in Europe.

- Innovations in transportation technology reduced trade costs substantially.

- New industrial military technologies increased the power of European states and the United States, and allowed these powers to forcibly open up markets across the world and extend their empires.

- A gradual move towards greater liberalization in European countries.

During the 19th century, globalization approached its form as a direct result of the Industrial Revolution. Industrialization allowed standardized production of household items using economies of scale while rapid population growth created sustained demand for commodities. In the 19th century, steamships reduced the cost of international transportation significantly and railroads made inland transportation cheaper. The transportation revolution occurred some time between 1820 and 1850.[37] More nations embraced international trade.[37] Globalization in this period was decisively shaped by nineteenth-century imperialism such as in Africa and Asia. The invention of shipping containers in 1956 helped advance the globalization of commerce.[50][51]

After World War II, work by politicians led to the agreements of the Bretton Woods Conference, in which major governments laid down the framework for international monetary policy, commerce, and finance, and the founding of several international institutions intended to facilitate economic growth by lowering trade barriers. Initially, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) led to a series of agreements to remove trade restrictions. GATT's successor was the World Trade Organization (WTO), which provided a framework for negotiating and formalizing trade agreements and a dispute resolution process. Exports nearly doubled from 8.5% of total gross world product in 1970 to 16.2% in 2001.[52] The approach of using global agreements to advance trade stumbled with the failure of the Doha Development Round of trade negotiation. Many countries then shifted to bilateral or smaller multilateral agreements, such as the 2011 United States–Korea Free Trade Agreement.

Since the 1970s, aviation has become increasingly affordable to middle classes in developed countries. Open skies policies and low-cost carriers have helped to bring competition to the market. In the 1990s, the growth of low-cost communication networks cut the cost of communicating between countries. More work can be performed using a computer without regard to location. This included accounting, software development, and engineering design.

Student exchange programs became popular after World War II, and are intended to increase the participants' understanding and tolerance of other cultures, as well as improving their language skills and broadening their social horizons. Between 1963 and 2006 the number of students studying in a foreign country increased 9 times.[53]

Since the 1980s, modern globalization has spread rapidly through the expansion of capitalism and neoliberal ideologies.[54] The implementation of neoliberal policies has allowed for the privatization of public industry, deregulation of laws or policies that interfered with the free flow of the market, as well as cut-backs to governmental social services.[55] These neoliberal policies were introduced to many developing countries in the form of structural adjustment programs (SAPs) that were implemented by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[54] These programs required that the country receiving monetary aid would open its markets to capitalism, privatize public industry, allow free trade, cut social services like healthcare and education and allow the free movement of giant multinational corporations.[56] These programs allowed the World Bank and the IMF to become global financial market regulators that would promote neoliberalism and the creation of free markets for multinational corporations on a global scale.[57]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the connectedness of the world's economies and cultures grew very quickly. This slowed down from the 1910s onward due to the World Wars and the Cold War,[58] but picked up again in the 1980s and 1990s.[59] The revolutions of 1989 and subsequent liberalization in many parts of the world resulted in a significant expansion of global interconnectedness. The migration and movement of people can also be highlighted as a prominent feature of the globalization process. In the period between 1965 and 1990, the proportion of the labor force migrating approximately doubled. Most migration occurred between the developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs).[60] As economic integration intensified workers moved to areas with higher wages and most of the developing world oriented toward the international market economy. The collapse of the Soviet Union not only ended the Cold War's division of the world – it also left the United States its sole policeman and an unfettered advocate of free market.[according to whom?] It also resulted in the growing prominence of attention focused on the movement of diseases, the proliferation of popular culture and consumer values, the growing prominence of international institutions like the UN, and concerted international action on such issues as the environment and human rights.[61] Other developments as dramatic were the Internet's becoming influential in connecting people across the world; As of June 2012[update], more than 2.4 billion people—over a third of the world's human population—have used the services of the Internet.[62][63] Growth of globalization has never been smooth. One influential event was the late 2000s recession, which was associated with lower growth (in areas such as cross-border phone calls and Skype usage) or even temporarily negative growth (in areas such as trade) of global interconnectedness.[64][65]

The China–United States trade war, starting in 2018, negatively affected trade between the two largest national economies. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic included a massive decline in tourism and international business travel as many countries temporarily closed borders. The 2021–2022 global supply chain crisis resulted from temporary shutdowns of manufacturing and transportation facilities, and labor shortages. Supply problems incentivized some switches to domestic production.[66] The economic impact of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine included a blockade of Ukrainian ports and international sanctions on Russia, resulting in some de-coupling of the Russian economy with global trade, especially with the European Union and other Western countries.

Modern consensus for the last 15 years regards globalization as having run its course and gone into decline.[67] A common argument for this is that trade has dropped since its peak in 2008, and never recovered since the Great Recession. New opposing views from some economists have argued such trends are a result of price drops and in actuality, trade volume is increasing, especially with agricultural products, natural resources and refined petroleum.[68][69]

Economic globalization

editEconomic globalization is the increasing economic interdependence of national economies across the world through a rapid increase in cross-border movement of goods, services, technology, and capital.[71] Whereas the globalization of business is centered around the diminution of international trade regulations as well as tariffs, taxes, and other impediments that suppresses global trade, economic globalization is the process of increasing economic integration between countries, leading to the emergence of a global marketplace or a single world market.[72] Depending on the paradigm, economic globalization can be viewed as either a positive or a negative phenomenon. Economic globalization comprises: globalization of production; which refers to the obtainment of goods and services from a particular source from locations around the globe to benefit from difference in cost and quality. Likewise, it also comprises globalization of markets; which is defined as the union of different and separate markets into a massive global marketplace. Economic globalization also includes[73] competition, technology, and corporations and industries.[71]

Current globalization trends can be largely accounted for by developed economies integrating with less developed economies by means of foreign direct investment, the reduction of trade barriers as well as other economic reforms, and, in many cases, immigration.[74]

International standards have made trade in goods and services more efficient. An example of such standard is the intermodal container. Containerization dramatically reduced the costs of transportation, supported the post-war boom in international trade, and was a major element in globalization.[50] International standards are set by the International Organization for Standardization, which is composed of representatives from various national standards organizations.

A multinational corporation, or worldwide enterprise,[75] is an organization that owns or controls the production of goods or services in one or more countries other than their home country.[76] It can also be referred to as an international corporation, a transnational corporation, or a stateless corporation.[77]

A free-trade area is the region encompassing a trade bloc whose member countries have signed a free-trade agreement (FTA). Such agreements involve cooperation between at least two countries to reduce trade barriers – import quotas and tariffs – and to increase trade of goods and services with each other.[78]

If people are also free to move between the countries, in addition to a free-trade agreement, it would also be considered an open border. Arguably, the most significant free-trade area in the world is the European Union, a politico-economic union of 27 member states that are primarily located in Europe. The EU has developed European Single Market through a standardized system of laws that apply in all member states. EU policies aim to ensure the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital within the internal market,[79]

Trade facilitation looks at how procedures and controls governing the movement of goods across national borders can be improved to reduce associated cost burdens and maximize efficiency while safeguarding legitimate regulatory objectives.

Global trade in services is also significant. For example, in India, business process outsourcing has been described as the "primary engine of the country's development over the next few decades, contributing broadly to GDP growth, employment growth, and poverty alleviation".[80][81]

William I. Robinson's theoretical approach to globalization is a critique of Wallerstein's World Systems Theory. He believes that the global capital experienced today is due to a new and distinct form of globalization which began in the 1980s. Robinson argues not only are economic activities expanded across national boundaries but also there is a transnational fragmentation of these activities.[82] One important aspect of Robinson's globalization theory is that production of goods are increasingly global. This means that one pair of shoes can be produced by six countries, each contributing to a part of the production process.

Cultural globalization

editCultural globalization refers to the transmission of ideas, meanings, and values around the world in such a way as to extend and intensify social relations.[83] This process is marked by the common consumption of cultures that have been diffused by the Internet, popular culture media, and international travel. This has added to processes of commodity exchange and colonization which have a longer history of carrying cultural meaning around the globe. The circulation of cultures enables individuals to partake in extended social relations that cross national and regional borders. The creation and expansion of such social relations is not merely observed on a material level. Cultural globalization involves the formation of shared norms and knowledge with which people associate their individual and collective cultural identities. It brings increasing interconnectedness among different populations and cultures.[84]

Cross-cultural communication is a field of study that looks at how people from differing cultural backgrounds communicate, in similar and different ways among themselves, and how they endeavor to communicate across cultures. Intercultural communication is a related field of study.

Cultural diffusion is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technologies, languages etc. Cultural globalization has increased cross-cultural contacts, but may be accompanied by a decrease in the uniqueness of once-isolated communities. For example, sushi is available in Germany as well as Japan, but Euro-Disney outdraws the city of Paris, potentially reducing demand for "authentic" French pastry.[85][86][87] Globalization's contribution to the alienation of individuals from their traditions may be modest compared to the impact of modernity itself, as alleged by existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. Globalization has expanded recreational opportunities by spreading pop culture, particularly via the Internet and satellite television. The cultural diffusion can create a homogenizing force, where globalization is seen as synonymous with homogenizing force via connectedness of markets, cultures, politics and the desire for modernizations through imperial countries sphere of influence.[88]

Religions were among the earliest cultural elements to globalize, being spread by force, migration, evangelists, imperialists, and traders. Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and more recently sects such as Mormonism are among those religions which have taken root and influenced endemic cultures in places far from their origins.[89]

Globalization has strongly influenced sports.[90] For example, the modern Olympic Games has athletes from more than 200 nations participating in a variety of competitions.[91] The FIFA World Cup is the most widely viewed and followed sporting event in the world, exceeding even the Olympic Games; a ninth of the entire population of the planet watched the 2006 FIFA World Cup Final.[92][93][94]

The term globalization implies transformation. Cultural practices including traditional music can be lost or turned into a fusion of traditions. Globalization can trigger a state of emergency for the preservation of musical heritage. Archivists may attempt to collect, record, or transcribe repertoires before melodies are assimilated or modified, while local musicians may struggle for authenticity and to preserve local musical traditions. Globalization can lead performers to discard traditional instruments. Fusion genres can become interesting fields of analysis.[95]

Music has an important role in economic and cultural development during globalization. Music genres such as jazz and reggae began locally and later became international phenomena. Globalization gave support to the world music phenomenon by allowing music from developing countries to reach broader audiences.[96] Though the term "World Music" was originally intended for ethnic-specific music, globalization is now expanding its scope such that the term often includes hybrid subgenres such as "world fusion", "global fusion", "ethnic fusion",[97] and worldbeat.[98][99]

Bourdieu claimed that the perception of consumption can be seen as self-identification and the formation of identity. Musically, this translates into each individual having their own musical identity based on likes and tastes. These likes and tastes are greatly influenced by culture, as this is the most basic cause for a person's wants and behavior. The concept of one's own culture is now in a period of change due to globalization. Also, globalization has increased the interdependency of political, personal, cultural, and economic factors.[101]

A 2005 UNESCO report[102] showed that cultural exchange is becoming more frequent from Eastern Asia, but that Western countries are still the main exporters of cultural goods. In 2002, China was the third largest exporter of cultural goods, after the UK and US. Between 1994 and 2002, both North America's and the European Union's shares of cultural exports declined while Asia's cultural exports grew to surpass North America. Related factors are the fact that Asia's population and area are several times that of North America. Americanization is related to a period of high political American clout and of significant growth of America's shops, markets and objects being brought into other countries.

Some critics of globalization argue that it harms the diversity of cultures. As a dominating country's culture is introduced into a receiving country through globalization, it can become a threat to the diversity of local culture. Some argue that globalization may ultimately lead to Westernization or Americanization of culture, where the dominating cultural concepts of economically and politically powerful Western countries spread and cause harm to local cultures.[103]

Globalization is a diverse phenomenon that relates to a multilateral political world and to the increase of cultural objects and markets between countries. The Indian experience particularly reveals the plurality of the impact of cultural globalization.[104]

Transculturalism is defined as "seeing oneself in the other".[105] Transcultural[106] is in turn described as "extending through all human cultures"[106] or "involving, encompassing, or combining elements of more than one culture".[107] Children brought up in transcultural backgrounds are sometimes called third-culture kids.

Political globalization

editPolitical globalization refers to the growth of the worldwide political system, both in size and complexity. That system includes national governments, their governmental and intergovernmental organizations as well as government-independent elements of global civil society such as international non-governmental organizations and social movement organizations. One of the key aspects of the political globalization is the declining importance of the nation-state and the rise of other actors on the political scene. William R. Thompson has defined it as "the expansion of a global political system, and its institutions, in which inter-regional transactions (including, but certainly not limited to trade) are managed".[108] Political globalization is one of the three main dimensions of globalization commonly found in academic literature, with the two other being economic globalization and cultural globalization.[12]

Intergovernmentalism is a term in political science with two meanings. The first refers to a theory of regional integration originally proposed by Stanley Hoffmann; the second treats states and the national government as the primary factors for integration. Multi-level governance is an approach in political science and public administration theory that originated from studies on European integration. Multi-level governance gives expression to the idea that there are many interacting authority structures at work in the emergent global political economy. It illuminates the intimate entanglement between the domestic and international levels of authority.

Some people are citizens of multiple nation-states. Multiple citizenship, also called dual citizenship or multiple nationality or dual nationality, is a person's citizenship status, in which a person is concurrently regarded as a citizen of more than one state under the laws of those states.

Increasingly, non-governmental organizations influence public policy across national boundaries, including humanitarian aid and developmental efforts.[110] Philanthropic organizations with global missions are also coming to the forefront of humanitarian efforts; charities such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Accion International, the Acumen Fund (now Acumen) and the Echoing Green have combined the business model with philanthropy, giving rise to business organizations such as the Global Philanthropy Group and new associations of philanthropists such as the Global Philanthropy Forum. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation projects include a current multibillion-dollar commitment to funding immunizations in some of the world's more impoverished but rapidly growing countries.[111] The Hudson Institute estimates total private philanthropic flows to developing countries at US$59 billion in 2010.[112]

As a response to globalization, some countries have embraced isolationist policies. For example, the North Korean government makes it very difficult for foreigners to enter the country and strictly monitors their activities when they do. Aid workers are subject to considerable scrutiny and excluded from places and regions the government does not wish them to enter. Citizens cannot freely leave the country.[113][114]

Globalization and gender

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Globalization has been a gendered process where giant multinational corporations have outsourced jobs to low-wage, low skilled, quota free economies like the ready made garment industry in Bangladesh where poor women make up the majority of labor force. Despite a large proportion of women workers in the garment industry, women are still heavily underemployed compared to men. Most women that are employed in the garment industry come from the countryside of Bangladesh triggering migration of women in search of garment work. It is still unclear as to whether or not access to paid work for women where it did not exist before has empowered them. The answers varied depending on whether it is the employers perspective or the workers and how they view their choices. Women workers did not see the garment industry as economically sustainable for them in the long run due to long hours standing and poor working conditions. Although women workers did show significant autonomy over their personal lives including their ability to negotiate with family, more choice in marriage, and being valued as a wage earner in the family. This did not translate into workers being able to collectively organize themselves in order to negotiate a better deal for themselves at work.[115]

Another example of outsourcing in manufacturing includes the maquiladora industry in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico where poor women make up the majority of the labor force. Women in the maquiladora industry have produced high levels of turnover not staying long enough to be trained compared to men. A gendered two tiered system within the maquiladora industry has been created that focuses on training and worker loyalty. Women are seen as being untrainable, placed in un-skilled, low wage jobs, while men are seen as more trainable with less turnover rates, and placed in more high skilled technical jobs. The idea of training has become a tool used against women to blame them for their high turnover rates which also benefit the industry keeping women as temporary workers.[116]

Other dimensions

editScholars also occasionally discuss other, less common dimensions of globalization, such as environmental globalization (the internationally coordinated practices and regulations, often in the form of international treaties, regarding environmental protection)[117] or military globalization (growth in global extent and scope of security relationships).[118] Those dimensions, however, receive much less attention the three described above, as academic literature commonly subdivides globalization into three major areas: economic globalization, cultural globalization and political globalization.[12]

Movement of people

editAn essential aspect of globalization is movement of people, and state-boundary limits on that movement have changed across history.[119] The movement of tourists and business people opened up over the last century. As transportation technology improved, travel time and costs decreased dramatically between the 18th and early 20th century. For example, travel across the Atlantic Ocean used to take up to 5 weeks in the 18th century, but around the time of the 20th century it took a mere 8 days.[120] Today, modern aviation has made long-distance transportation quick and affordable.

Tourism is travel for pleasure. The developments in technology and transportation infrastructure, such as jumbo jets, low-cost airlines, and more accessible airports have made many types of tourism more affordable. At any given moment half a million people are in the air.[121] International tourist arrivals surpassed the milestone of 1 billion tourists globally for the first time in 2012.[122] A visa is a conditional authorization granted by a country to a foreigner, allowing them to enter and temporarily remain within, or to leave that country. Some countries – such as those in the Schengen Area – have agreements with other countries allowing each other's citizens to travel between them without visas (for example, Switzerland is part of a Schengen Agreement allowing easy travel for people from countries within the European Union). The World Tourism Organization announced that the number of tourists who require a visa before traveling was at its lowest level ever in 2015.[123]

Immigration is the international movement of people into a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle or reside there, especially as permanent residents or naturalized citizens, or to take-up employment as a migrant worker or temporarily as a foreign worker.[124][125][126] According to the International Labour Organization, as of 2014[update] there were an estimated 232 million international migrants in the world (defined as persons outside their country of origin for 12 months or more) and approximately half of them were estimated to be economically active (i.e. being employed or seeking employment).[127] International movement of labor is often seen as important to economic development. For example, freedom of movement for workers in the European Union means that people can move freely between member states to live, work, study or retire in another country.

Globalization is associated with a dramatic rise in international education. The development of global cross-cultural competence in the workforce through ad-hoc training has deserved increasing attention in recent times.[129][130] More and more students are seeking higher education in foreign countries and many international students now consider overseas study a stepping-stone to permanent residency within a country.[131] The contributions that foreign students make to host nation economies, both culturally and financially has encouraged major players to implement further initiatives to facilitate the arrival and integration of overseas students, including substantial amendments to immigration and visa policies and procedures.[53]

A transnational marriage is a marriage between two people from different countries. A variety of special issues arise in marriages between people from different countries, including those related to citizenship and culture, which add complexity and challenges to these kinds of relationships. In an age of increasing globalization, where a growing number of people have ties to networks of people and places across the globe, rather than to a current geographic location, people are increasingly marrying across national boundaries. Transnational marriage is a by-product of the movement and migration of people.

Movement of information

edit| Region | 2005 | 2010 | 2017 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 2% | 10% | 21.8% | 37% |

| Americas | 36% | 49% | 65.9% | 87% |

| Arab States | 8% | 26% | 43.7% | 69% |

| Asia and Pacific | 9% | 23% | 43.9% | 66% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

10% | 34% | 67.7% | 89% |

| Europe | 46% | 67% | 79.6% | 91% |

Before electronic communications, long-distance communications relied on mail. Speed of global communications was limited by the maximum speed of courier services (especially horses and ships) until the mid-19th century. The electric telegraph was the first method of instant long-distance communication. For example, before the first transatlantic cable, communications between Europe and the Americas took weeks because ships had to carry mail across the ocean. The first transatlantic cable reduced communication time considerably, allowing a message and a response in the same day. Lasting transatlantic telegraph connections were achieved in the 1865–1866. The first wireless telegraphy transmitters were developed in 1895.

The Internet has been instrumental in connecting people across geographical boundaries. For example, Facebook is a social networking service which has more than 1.65 billion monthly active users as of 31 March 2016[update].[133]

Globalization can be spread by Global journalism which provides massive information and relies on the internet to interact, "makes it into an everyday routine to investigate how people and their actions, practices, problems, life conditions, etc. in different parts of the world are interrelated. possible to assume that global threats such as climate change precipitate the further establishment of global journalism."[134]

Globalization and disease

editIn the current era of globalization, the world is more interdependent than at any other time. Efficient and inexpensive transportation has left few places inaccessible, and increased global trade has brought more and more people into contact with animal diseases that have subsequently jumped species barriers (see zoonosis).[135]

Coronavirus disease 2019, abbreviated COVID-19, first appeared in Wuhan, China in November 2019. More than 180 countries have reported cases since then.[136] As of April 6, 2020[update], the U.S. has the most confirmed active cases in the world.[137] More than 3.4 million people from the worst-affected countries entered the U.S. in the first three months since the inception of the COVID-19 pandemic.[138] This has caused a detrimental impact on the global economy, particularly for SME's and Microbusinesses with unlimited liability/self-employed, leaving them vulnerable to financial difficulties, increasing the market share for oligopolistic markets as well as increasing the barriers of entry.

Measurement

editOne index of globalization is the KOF Index of Globalization, which measures three important dimensions of globalization: economic, social, and political.[139] Another is the A.T. Kearney / Foreign Policy Magazine Globalization Index.[140]

|

|

Measurements of economic globalization typically focus on variables such as trade, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Gross Domestic Product (GDP), portfolio investment, and income. However, newer indices attempt to measure globalization in more general terms, including variables related to political, social, cultural, and even environmental aspects of globalization.[141][142]

The DHL Global Connectedness Index studies four main types of cross-border flow: trade (in both goods and services), information, people (including tourists, students, and migrants), and capital. It shows that the depth of global integration fell by about one-tenth after 2008, but by 2013 had recovered well above its pre-crash peak.[25][64] The report also found a shift of economic activity to emerging economies.[25]

Support and criticism

editReactions to processes contributing to globalization have varied widely with a history as long as extraterritorial contact and trade. Philosophical differences regarding the costs and benefits of such processes give rise to a broad-range of ideologies and social movements. Proponents of economic growth, expansion, and development, in general, view globalizing processes as desirable or necessary to the well-being of human society.[143]

Antagonists view one or more globalizing processes as detrimental to social well-being on a global or local scale;[143] this includes those who focus on social or natural sustainability of long-term and continuous economic expansion, the social structural inequality caused by these processes, and the colonial, imperialistic, or hegemonic ethnocentrism, cultural assimilation and cultural appropriation that underlie such processes.

Globalization tends to bring people into contact with foreign people and cultures. Xenophobia is the fear of that which is perceived to be foreign or strange.[144][145] Xenophobia can manifest itself in many ways involving the relations and perceptions of an ingroup towards an outgroup, including a fear of losing identity, suspicion of its activities, aggression, and desire to eliminate its presence to secure a presumed purity.[146]

Critiques of globalization generally stem from discussions surrounding the impact of such processes on the planet as well as the human costs. They challenge directly traditional metrics, such as GDP, and look to other measures, such as the Gini coefficient[147] or the Happy Planet Index,[148] and point to a "multitude of interconnected fatal consequences–social disintegration, a breakdown of democracy, more rapid and extensive deterioration of the environment, the spread of new diseases, increasing poverty and alienation"[149] which they claim are the unintended consequences of globalization. Others point out that, while the forces of globalization have led to the spread of western-style democracy, this has been accompanied by an increase in inter-ethnic tension and violence as free market economic policies combine with democratic processes of universal suffrage as well as an escalation in militarization to impose democratic principles and as a means to conflict resolution.[150]

On 9 August 2019, Pope Francis denounced isolationism and hinted that the Catholic Church will embrace globalization at the October 2019 Amazonia Synod, stating "the whole is greater than the parts. Globalization and unity should not be conceived as a sphere, but as a polyhedron: each people retains its identity in unity with others"[151]

Public opinion

editThis article needs to be updated. (December 2019) |

As a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, globalization is considered by some as a form of capitalist expansion which entails the integration of local and national economies into a global, unregulated market economy.[152] A 2005 study by Peer Fis and Paul Hirsch found a large increase in articles negative towards globalization in the years prior. In 1998, negative articles outpaced positive articles by two to one.[153] The number of newspaper articles showing negative framing rose from about 10% of the total in 1991 to 55% of the total in 1999. This increase occurred during a period when the total number of articles concerning globalization nearly doubled.[153]

A number of international polls have shown that residents of Africa and Asia tend to view globalization more favorably than residents of Europe or North America. In Africa, a Gallup poll found that 70% of the population views globalization favorably.[154] The BBC found that 50% of people believed that economic globalization was proceeding too rapidly, while 35% believed it was proceeding too slowly.[155]

In 2004, Philip Gordon stated that "a clear majority of Europeans believe that globalization can enrich their lives, while believing the European Union can help them take advantage of globalization's benefits while shielding them from its negative effects". The main opposition consisted of socialists, environmental groups, and nationalists. Residents of the EU did not appear to feel threatened by globalization in 2004. The EU job market was more stable and workers were less likely to accept wage/benefit cuts. Social spending was much higher than in the US.[156] In a Danish poll in 2007, 76% responded that globalization is a good thing.[157]

Fiss, et al., surveyed US opinion in 1993. Their survey showed that, in 1993, more than 40% of respondents were unfamiliar with the concept of globalization. When the survey was repeated in 1998, 89% of the respondents had a polarized view of globalization as being either good or bad. At the same time, discourse on globalization, which began in the financial community before shifting to a heated debate between proponents and disenchanted students and workers. Polarization increased dramatically after the establishment of the WTO in 1995; this event and subsequent protests led to a large-scale anti-globalization movement.[153] Initially, college educated workers were likely to support globalization. Less educated workers, who were more likely to compete with immigrants and workers in developing countries, tended to be opponents. The situation changed after the Great Recession. According to a 1997 poll 58% of college graduates said globalization had been good for the US. By 2008 only 33% thought it was good. Respondents with high school education also became more opposed.[158]

According to Takenaka Heizo and Chida Ryokichi, as of 1998[update] there was a perception in Japan that the economy was "Small and Frail". However, Japan was resource-poor and used exports to pay for its raw materials. Anxiety over their position caused terms such as internationalization and globalization to enter everyday language. However, Japanese tradition was to be as self-sufficient as possible, particularly in agriculture.[159]

Many in developing countries see globalization as a positive force that lifts them out of poverty.[160] Those opposing globalization typically combine environmental concerns with nationalism. Opponents consider governments as agents of neo-colonialism that are subservient to multinational corporations.[161] Much of this criticism comes from the middle class; the Brookings Institution suggested this was because the middle class perceived upwardly mobile low-income groups as threatening to their economic security.[162]

Economics

editThe literature analyzing the economics of free trade is extremely rich with extensive work having been done on the theoretical and empirical effects. Though it creates winners and losers, the broad consensus among economists is that free trade is a large and unambiguous net gain for society.[163][164] In a 2006 survey of 83 American economists, "87.5% agree that the U.S. should eliminate remaining tariffs and other barriers to trade" and "90.1% disagree with the suggestion that the U.S. should restrict employers from outsourcing work to foreign countries."[165]

Quoting Harvard economics professor N. Gregory Mankiw, "Few propositions command as much consensus among professional economists as that open world trade increases economic growth and raises living standards."[166] In a survey of leading economists, none disagreed with the notion that "freer trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment."[167] Most economists would agree that although increasing returns to scale might mean that certain industry could settle in a geographical area without any strong economic reason derived from comparative advantage, this is not a reason to argue against free trade because the absolute level of output enjoyed by both "winner" and "loser" will increase with the "winner" gaining more than the "loser" but both gaining more than before in an absolute level.

In the book The End of Poverty, Jeffrey Sachs discusses how many factors can affect a country's ability to enter the world market, including government corruption; legal and social disparities based on gender, ethnicity, or caste; diseases such as AIDS and malaria; lack of infrastructure (including transportation, communications, health, and trade); unstable political landscapes; protectionism; and geographic barriers.[168] Jagdish Bhagwati, a former adviser to the U.N. on globalization, holds that, although there are obvious problems with overly rapid development, globalization is a very positive force that lifts countries out of poverty by causing a virtuous economic cycle associated with faster economic growth.[160] However, economic growth does not necessarily mean a reduction in poverty; in fact, the two can coexist. Economic growth is conventionally measured using indicators such as GDP and GNI that do not accurately reflect the growing disparities in wealth.[169] Additionally, Oxfam International argues that poor people are often excluded from globalization-induced opportunities "by a lack of productive assets, weak infrastructure, poor education and ill-health;"[170] effectively leaving these marginalized groups in a poverty trap. Economist Paul Krugman is another staunch supporter of globalization and free trade with a record of disagreeing with many critics of globalization. He argues that many of them lack a basic understanding of comparative advantage and its importance in today's world.[171]

The flow of migrants to advanced economies has been claimed to provide a means through which global wages converge. An IMF study noted a potential for skills to be transferred back to developing countries as wages in those a countries rise.[11] Lastly, the dissemination of knowledge has been an integral aspect of globalization. Technological innovations (or technological transfer) are conjectured to benefit most developing and least developing countries (LDCs), as for example in the adoption of mobile phones.[60]

There has been a rapid economic growth in Asia after embracing market orientation-based economic policies that encourage private property rights, free enterprise and competition. In particular, in East Asian developing countries, GDP per head rose at 5.9% a year from 1975 to 2001 (according to 2003 Human Development Report[172] of UNDP). Like this, the British economic journalist Martin Wolf says that incomes of poor developing countries, with more than half the world's population, grew substantially faster than those of the world's richest countries that remained relatively stable in its growth, leading to reduced international inequality and the incidence of poverty.

Certain demographic changes in the developing world after active economic liberalization and international integration resulted in rising general welfare and, hence, reduced inequality. According to Wolf, in the developing world as a whole, life expectancy rose by four months each year after 1970 and infant mortality rate declined from 107 per thousand in 1970 to 58 in 2000 due to improvements in standards of living and health conditions. Also, adult literacy in developing countries rose from 53% in 1970 to 74% in 1998 and much lower illiteracy rate among the young guarantees that rates will continue to fall as time passes. Furthermore, the reduction in fertility rate in the developing world as a whole from 4.1 births per woman in 1980 to 2.8 in 2000 indicates improved education level of women on fertility, and control of fewer children with more parental attention and investment.[174] Consequently, more prosperous and educated parents with fewer children have chosen to withdraw their children from the labor force to give them opportunities to be educated at school improving the issue of child labor. Thus, despite seemingly unequal distribution of income within these developing countries, their economic growth and development have brought about improved standards of living and welfare for the population as a whole.

Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) growth among post-1980 globalizing countries accelerated from 1.4 percent a year in the 1960s and 2.9 percent a year in the 1970s to 3.5 percent in the 1980s and 5.0 percent in the 1990s. This acceleration in growth seems even more remarkable given that the rich countries saw steady declines in growth from a high of 4.7 percent in the 1960s to 2.2 percent in the 1990s. Also, the non-globalizing developing countries seem to fare worse than the globalizers, with the former's annual growth rates falling from highs of 3.3 percent during the 1970s to only 1.4 percent during the 1990s. This rapid growth among the globalizers is not simply due to the strong performances of China and India in the 1980s and 1990s—18 out of the 24 globalizers experienced increases in growth, many of them quite substantial.[175]

The globalization of the late 20th and early 21st centuries has led to the resurfacing of the idea that the growth of economic interdependence promotes peace.[176] This idea had been very powerful during the globalization of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and was a central doctrine of classical liberals of that era, such as the young John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946).[177]

Some opponents of globalization see the phenomenon as a promotion of corporate interests.[178] They also claim that the increasing autonomy and strength of corporate entities shapes the political policy of countries.[179][180] They advocate global institutions and policies that they believe better address the moral claims of poor and working classes as well as environmental concerns.[181] Economic arguments by fair trade theorists claim that unrestricted free trade benefits those with more financial leverage (i.e. the rich) at the expense of the poor.[182]

Globalization allows corporations to outsource manufacturing and service jobs from high-cost locations, creating economic opportunities with the most competitive wages and worker benefits.[80] Critics of globalization say that it disadvantages poorer countries. While it is true that free trade encourages globalization among countries, some countries try to protect their domestic suppliers. The main export of poorer countries is usually agricultural productions. Larger countries often subsidize their farmers (e.g., the EU's Common Agricultural Policy), which lowers the market price for foreign crops.[183]

Global democracy

editDemocratic globalization is a movement towards an institutional system of global democracy that would give world citizens a say in political organizations. This would, in their view, bypass nation-states, corporate oligopolies, ideological non-governmental organizations (NGO), political cults and mafias. One of its most prolific proponents is the British political thinker David Held. Advocates of democratic globalization argue that economic expansion and development should be the first phase of democratic globalization, which is to be followed by a phase of building global political institutions. Francesco Stipo, Director of the United States Association of the Club of Rome, advocates unifying nations under a world government, suggesting that it "should reflect the political and economic balances of world nations. A world confederation would not supersede the authority of the State governments but rather complement it, as both the States and the world authority would have power within their sphere of competence".[184] Former Canadian Senator Douglas Roche, O.C., viewed globalization as inevitable and advocated creating institutions such as a directly elected United Nations Parliamentary Assembly to exercise oversight over unelected international bodies.[185]

Global civics

editGlobal civics suggests that civics can be understood, in a global sense, as a social contract between global citizens in the age of interdependence and interaction. The disseminators of the concept define it as the notion that we have certain rights and responsibilities towards each other by the mere fact of being human on Earth.[186] World citizen has a variety of similar meanings, often referring to a person who disapproves of traditional geopolitical divisions derived from national citizenship. An early incarnation of this sentiment can be found in Socrates, whom Plutarch quoted as saying: "I am not an Athenian, or a Greek, but a citizen of the world."[187] In an increasingly interdependent world, world citizens need a compass to frame their mindsets and create a shared consciousness and sense of global responsibility in world issues such as environmental problems and nuclear proliferation.[188]

Baha'i-inspired author Meyjes, while favoring the single world community and emergent global consciousness, warns of globalization[189] as a cloak for an expeditious economic, social, and cultural Anglo-dominance that is insufficiently inclusive to inform the emergence of an optimal world civilization. He proposes a process of "universalization" as an alternative.

Cosmopolitanism is the proposal that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality. A person who adheres to the idea of cosmopolitanism in any of its forms is called a cosmopolitan or cosmopolite.[190] A cosmopolitan community might be based on an inclusive morality, a shared economic relationship, or a political structure that encompasses different nations. The cosmopolitan community is one in which individuals from different places (e.g. nation-states) form relationships based on mutual respect. For instance, Kwame Anthony Appiah suggests the possibility of a cosmopolitan community in which individuals from varying locations (physical, economic, etc.) enter relationships of mutual respect despite their differing beliefs (religious, political, etc.).[191]

Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan popularized the term Global Village beginning in 1962.[192] His view suggested that globalization would lead to a world where people from all countries will become more integrated and aware of common interests and shared humanity.[193]

International cooperation

editMilitary cooperation – Past examples of international cooperation exist. One example is the security cooperation between the United States and the former Soviet Union after the end of the Cold War, which astonished international society. Arms control and disarmament agreements, including the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (see START I, START II, START III, and New START) and the establishment of NATO's Partnership for Peace, the Russia NATO Council, and the G8 Global Partnership against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction, constitute concrete initiatives of arms control and de-nuclearization. The US–Russian cooperation was further strengthened by anti-terrorism agreements enacted in the wake of 9/11.[194]

Environmental cooperation – One of the biggest successes of environmental cooperation has been the agreement to reduce chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) emissions, as specified in the Montreal Protocol, in order to stop ozone depletion. The most recent debate around nuclear energy and the non-alternative coal-burning power plants constitutes one more consensus on what not to do. Thirdly, significant achievements in IC can be observed through development studies.[194]

Economic cooperation – One of the biggest challenges in 2019 with globalization is that many believe the progress made in the past decades are now back tracking. The back tracking of globalization has coined the term "Slobalization." Slobalization is a new, slower pattern of globalization.[195]

Anti-globalization movement

editAnti-globalization, or counter-globalization,[196] consists of a number of criticisms of globalization but, in general, is critical of the globalization of corporate capitalism.[197] The movement is also commonly referred to as the alter-globalization movement, anti-globalist movement, anti-corporate globalization movement,[198] or movement against neoliberal globalization. Opponents of globalization argue that power and respect in terms of international trade between the developed and underdeveloped countries of the world are unequally distributed.[199] The diverse subgroups that make up this movement include some of the following: trade unionists, environmentalists, anarchists, land rights and indigenous rights activists, organizations promoting human rights and sustainable development, opponents of privatization, and anti-sweatshop campaigners.[200]

In The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, Christopher Lasch analyzed[201] the widening gap between the top and bottom of the social composition in the United States. For him, our epoch is determined by a social phenomenon: the revolt of the elites, in reference to The Revolt of the Masses (1929) by the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset. According to Lasch, the new elites, i.e. those who are in the top 20% in terms of income, through globalization which allows total mobility of capital, no longer live in the same world as their fellow-citizens. In this, they oppose the old bourgeoisie of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which was constrained by its spatial stability to a minimum of rooting and civic obligations. Globalization, according to the sociologist, has turned elites into tourists in their own countries. The denationalization of business enterprise tends to produce a class who see themselves as "world citizens, but without accepting ... any of the obligations that citizenship in a polity normally implies". Their ties to an international culture of work, leisure, information – make many of them deeply indifferent to the prospect of national decline. Instead of financing public services and the public treasury, new elites are investing their money in improving their voluntary ghettos: private schools in their residential neighborhoods, private police, garbage collection systems. They have "withdrawn from common life". Composed of those who control the international flows of capital and information, who preside over philanthropic foundations and institutions of higher education, manage the instruments of cultural production and thus fix the terms of public debate. So, the political debate is limited mainly to the dominant classes and political ideologies lose all contact with the concerns of the ordinary citizen. The result of this is that no one has a likely solution to these problems and that there are furious ideological battles on related issues. However, they remain protected from the problems affecting the working classes: the decline of industrial activity, the resulting loss of employment, the decline of the middle class, increasing the number of the poor, the rising crime rate, growing drug trafficking, the urban crisis.

D.A. Snow et al. contend that the anti-globalization movement is an example of a new social movement, which uses tactics that are unique and use different resources than previously used before in other social movements.[202]

One of the most infamous tactics of the movement is the Battle of Seattle in 1999, where there were protests against the World Trade Organization's Third Ministerial Meeting. All over the world, the movement has held protests outside meetings of institutions such as the WTO, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, and the Group of Eight (G8).[200] Within the Seattle demonstrations the protesters that participated used both creative and violent tactics to gain the attention towards the issue of globalization.

Opposition to capital market integration

editCapital markets have to do with raising and investing money in various human enterprises. Increasing integration of these financial markets between countries leads to the emergence of a global capital marketplace or a single world market. In the long run, increased movement of capital between countries tends to favor owners of capital more than any other group; in the short run, owners and workers in specific sectors in capital-exporting countries bear much of the burden of adjusting to increased movement of capital.[203]

Those opposed to capital market integration on the basis of human rights issues are especially disturbed[according to whom?] by the various abuses which they think are perpetuated by global and international institutions that, they say, promote neoliberalism without regard to ethical standards. Common targets include the World Bank (WB), International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) and free trade treaties like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) and the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). In light of the economic gap between rich and poor countries, movement adherents claim free trade without measures in place to protect the under-capitalized will contribute only to the strengthening the power of industrialized nations (often termed the "North" in opposition to the developing world's "South").[204][better source needed]

Anti-corporatism and anti-consumerism

editCorporatist ideology, which privileges the rights of corporations (artificial or juridical persons) over those of natural persons, is an underlying factor in the recent rapid expansion of global commerce.[205] In recent years, there have been an increasing number of books (Naomi Klein's 2000 No Logo, for example) and films (e.g. The Corporation & Surplus) popularizing an anti-corporate ideology to the public.

A related contemporary ideology, consumerism, which encourages the personal acquisition of goods and services, also drives globalization.[206] Anti-consumerism is a social movement against equating personal happiness with consumption and the purchase of material possessions. Concern over the treatment of consumers by large corporations has spawned substantial activism, and the incorporation of consumer education into school curricula. Social activists hold materialism is connected to global retail merchandizing and supplier convergence, war, greed, anomie, crime, environmental degradation, and general social malaise and discontent. One variation on this topic is activism by postconsumers, with the strategic emphasis on moving beyond addictive consumerism.[207]

Global justice and inequality

editGlobal justice

editThe global justice movement is the loose collection of individuals and groups—often referred to as a "movement of movements"—who advocate fair trade rules and perceive current institutions of global economic integration as problems.[209] The movement is often labeled an anti-globalization movement by the mainstream media. Those involved, however, frequently deny that they are anti-globalization, insisting that they support the globalization of communication and people and oppose only the global expansion of corporate power.[210] The movement is based in the idea of social justice, desiring the creation of a society or institution based on the principles of equality and solidarity, the values of human rights, and the dignity of every human being.[211][212][213] Social inequality within and between nations, including a growing global digital divide, is a focal point of the movement. Many nongovernmental organizations have now arisen to fight these inequalities that many in Latin America, Africa and Asia face. A few very popular and well known non-governmental organizations (NGOs) include: War Child, Red Cross, Free The Children and CARE International. They often create partnerships where they work towards improving the lives of those who live in developing countries by building schools, fixing infrastructure, cleaning water supplies, purchasing equipment and supplies for hospitals, and other aid efforts.

Social inequality

editThe economies of the world have developed unevenly, historically, such that entire geographical regions were left mired in poverty and disease while others began to reduce poverty and disease on a wholesale basis. From around 1980 through at least 2011, the GDP gap, while still wide, appeared to be closing and, in some more rapidly developing countries, life expectancies began to rise.[214] If we look at the Gini coefficient for world income, since the late 1980s, the gap between some regions has markedly narrowed—between Asia and the advanced economies of the West, for example—but huge gaps remain globally. Overall equality across humanity, considered as individuals, has improved very little. Within the decade between 2003 and 2013, income inequality grew even in traditionally egalitarian countries like Germany, Sweden and Denmark. With a few exceptions—France, Japan, Spain—the top 10 percent of earners in most advanced economies raced ahead, while the bottom 10 percent fell further behind.[215] By 2013, 85 multibillionaires had amassed wealth equivalent to all the wealth owned by the poorest half (3.5 billion) of the world's total population of 7 billion.[216]