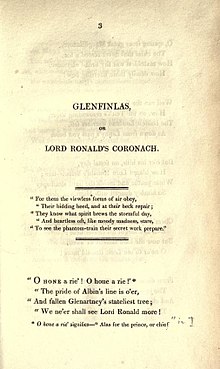

“Glenfinlas; or, Lord Ronald's Coronach” by Walter Scott, written in 1798 and first published in 1800, was, as Scott remembered it, his first original poem as opposed to translations from the German.[1] A short narrative of 264 lines, it tells a supernatural story based on a Highland legend. Though highly appreciated by many 19th century readers and critics it is now overshadowed by his later and longer poems.

Synopsis

edit“Glenfinlas” opens with a lament on the passing of the Highland chieftain Lord Ronald, before moving on to the describe the visit paid to him by Moy, another chief from distant Scottish islands, who we are told has studied the occult and has the second sight. The two go on a hunting expedition, unaccompanied by any of their followers, and after three days retire to a primitive hunting lodge in the wilds of Glenfinlas. Ronald says that his sweetheart Mary is herself out hunting along with her sister Flora; he proposes that Moy should win over Flora by the playing of his harp, leaving Ronald free to court the unchaperoned Mary.

Moy replies that his heart is too low-spirited for such things, that he has had a vision of the sisters’ shipwreck, and a presentiment that Ronald himself will die. Ronald mocks Moy's gloomy thoughts and goes off to keep a tryst with Mary in a nearby dell, alone except for his hounds. Presently the hounds return without Ronald. Night falls, and at midnight a huntress appears, dressed in water-soaked green clothes and with wet hair. She begins to dry herself before the fire, and asks Moy if he has seen Ronald. She last saw him, she says, wandering with another green-clad woman. Moy is afraid to go out into the ghost-haunted darkness to look for them, but the woman tries to shame him out, and shows that she knows more of Moy than he realizes:

Not so, by high Dunlathmon’s fire,

Thy heart was froze to love and joy,

When gaily rung thy raptured lyre

To wanton Morna’s melting eye.

Angry and afraid, Moy replies,

And thou! when by the blazing oak

I lay, to her and love resign’d,

Say, rode ye on the eddying smoke,

Or sail’d ye on the midnight wind?

Not thine a race of mortal blood

Nor old Glengyle’s pretended line;

Thy dame, the Lady of the Flood—

Thy sire, the Monarch of the Mine.

The strange woman, revealed as a spirit, flies away. Unearthly laughter is heard overhead, then there falls first a rain of blood, then a dismembered arm, and finally the bloody head of Ronald. Finally we are told that Glenfinlas will forever after be avoided by all travellers for fear of the Ladies of the Glen, and the poet returns to his initial lament for Lord Ronald.

Composition

editIn 1797 the popular novelist and poet Matthew Gregory “Monk” Lewis was shown copies of Scott's “Lenore” and “The Wild Huntsman”, both translations from Bürger, and immediately contacted him to ask for contributions to a collection of Gothic poems by various hands, provisionally called Tales of Terror.[2] One of the ballads Scott wrote for Lewis the following year was “Glenfinlas”.[3] It is based on a Highland legend which belongs to an international folktale type found from Greece and Brittany to Samoa and New Caledonia.[4][5] Scott himself summarised the legend thus:

While two Highland hunters were passing the night in a solitary bothy (a hut built for the purpose of hunting) and making merry over their venison and whisky, one of them expressed a wish that they had pretty lasses to complete their party. The words were scarcely uttered, when two beautiful young women, habited in green, entered the hut, dancing and singing. One of the hunters was seduced by the siren who attached herself particularly to him, to leave the hut: the other remained, and, suspicious of the fair seducers, continued to play upon a trump, or Jew's harp, some strain, consecrated to the Virgin Mary. Day at length came, and the temptress vanished. Searching in the forest, he found the bones of his unfortunate friend, who had been torn to pieces and devoured by the fiend into whose toils he had fallen. The place was thence called the Glen of the Green Women.[1]

On completing the poem Scott sent it to Lewis, who responded with a list of supposed faults of rhyme and rhythm. Comparing these with other criticisms made on the poem by his friends Scott found that they almost perfectly cancelled one another out. This persuaded him never to act on detailed criticisms of his poems from friends, only on blanket condemnations.[6]

Publication

editScott published “Glenfinlas” first of all in Tales of Wonder, as Lewis's project was finally called. Though the date 1801 appears on this book's imprint it was actually issued on 27 November 1800. Several other of his early poems appeared in the same collection, including “The Eve of St. John”. “Glenfinlas” was next included in Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802), a collection of traditional ballads alongside some modern imitations.[7][8] In 1805 he published his first long narrative poem, The Lay of the Last Minstrel, which proved to be such a sensational success with both readers and critics that its publisher, Longman, followed it up with a volume of Scott's original poems from the Minstrelsy together with some of his translations and lyric poems. These Ballads and Lyrical Pieces appeared on 20 September 1806, and proved to be a success in their own right, with 7000 copies being sold. [9][10][11]

Criticism

editIn the critical press the reception of Scott's early poems on their first appearance in print was, on the whole, encouraging. Though the reviews of Matthew Lewis's Tales of Wonder were largely unfriendly, he noted that “Amidst the general depreciation…my small share of the obnoxious publication was dismissed without censure, and in some cases obtained praise from the critics”; the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border was ringingly applauded for both its traditional and original ballads.[12][13] To the poet Anna Seward, who expressed her delight with “Glenfinlas”, Scott reported that “all Scotchmen prefer the 'Eve of St. John' to 'Glenfinlas', and most of my English friends entertain precisely an opposite opinion”.[14][15] He himself took the Scottish view.[16][3]

In 1837 his son-in-law and biographer J. G. Lockhart reluctantly half-agreed with those critics who, he tells us, thought that the German influences on Scott did not suit the poem's Celtic theme, and that the original legend was more moving than Scott's elaboration of it.[17] Nevertheless, some 19th century critics rated it very high among Scott's poems.[18] In 1897 the critic George Saintsbury judged “Glenfinlas” and “The Eve” to be the poems in which Scott first found his true voice, though he preferred “The Eve”.[19] 20th and 21st century critics have generally been more severe. Among Scott's biographers, John Buchan thought it “prentice work, full of dubious echoes and conventional artifice”,[20] S. Fowler Wright found the ballad unsatisfactory because the original story has too little variety of incident,[21] and Edgar Johnson thought the poem too slow, its language sometimes over-luscious, and the intended horror of its climax unachieved.[22] Recently the critic Terence Hoagwood complained that the poem is less vivid than “The Eve”, and its morality (like that of “Christabel” and “La Belle Dame sans Merci”) is misogynistic.[23]

Notes

edit- ^ a b Robertson 1971, p. 683.

- ^ Johnson 1970, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b Corson 1979, p. 7.

- ^ Lang, Andrew (1906). Sir Walter Scott. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 35–36. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Lang, Andrew (1899). The Homeric Hymns. New York: Longmans, Green. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9783847205708.

- ^ Johnson 1970, p. 164.

- ^ Corson 1979, p. 8.

- ^ "Walter Scott: Literary Beginnings". The Walter Scott Digital Archive. Edinburgh University Library. 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Johnson 1970, pp. 225–227.

- ^ Lockhart 1895, p. 143.

- ^ Todd, William B.; Bowden, Ann (1998). Sir Walter Scott: A Bibliographical History, 1796–1832. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press. p. 77. ISBN 1884718647. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Lockhart 1895, p. 94.

- ^ Johnson 1970, p. 188.

- ^ Lockhart 1895, p. 96.

- ^ Johnson 1970, p. 187.

- ^ Grierson, H. J. C., ed. (1932). The Letters of Sir Walter Scott, 1787–1807. London: Constable. p. 93.

- ^ Lockhart 1895, p. 84.

- ^ Hutton, Richard H. (1894) [1878]. Sir Walter Scott. London: Macmillan. p. 40. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Saintsbury, George (1897). Sir Walter Scott. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. p. 25. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Buchan, John (1932). Sir Walter Scott. London: Cassell. p. 57. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Wright, S. Fowler (1971) [1932]. The Life of Sir Walter Scott. New York: Haskell House. p. 112. ISBN 9781434444608. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Johnson 1970, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Hoagwood, Terence Allan (2010). From Song to Print: Romantic Pseudo-Songs. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 9780230609839. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

References

edit- Corson, James (1979). Notes and Index to Sir Herbert Grierson's Edition of the Letters of Sir Walter Scott. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198127189.

- Johnson, Edgar (1970). Sir Walter Scott: The Great Unknown. Volume 1: 1771–1821. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0241017610.

- Lockhart, J. G. (1895) [1837–1838]. The Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. London: Adam & Charles Black.

- Robertson, J. Logie, ed. (1971) [1904]. Scott: Poetical Works. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192541420.