Ghirardelli Square is a landmark public square at the foot of Russian Hill and adjacent to the Aquatic Park Historic District in San Francisco. It is often considered to be part of the tourist attractions at nearby Fisherman's Wharf. A portion of the area was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 as Pioneer Woolen Mills and D. Ghirardelli Company.

Pioneer Woolen Mills and D. Ghirardelli Company | |

Andrea, the fountain in Ghirardelli Square by Ruth Asawa | |

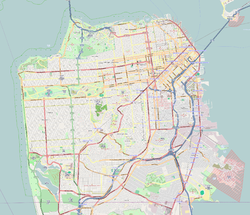

| Location | San Francisco, California, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°48′21″N 122°25′23″W / 37.8059°N 122.4230°W |

| Architect | William S. Mooser Sr., William S. Mooser |

| NRHP reference No. | 82002249[1] |

| SFDL No. | 30 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 29, 1982 |

| Designated SFDL | 1970[2] |

The square once featured over 40 specialty shops and restaurants. Some of the original shops and restaurants still occupy the square.

History

editIn 1893, Domenico Ghirardelli purchased the entire city block in order to make it into the headquarters of the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company. In the early 1960s, the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company was bought by the Golden Grain Macaroni Company, which moved the headquarters off-site to San Leandro and put the square up for sale.

San Franciscan William M. Roth and his mother, Lurline Matson Roth, bought the land in 1962 to prevent the square from being replaced with an apartment building. The Roths hired landscape architect Lawrence Halprin[3] and the firm Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons to convert the square and its historic brick structures to an integrated restaurant and retail complex,[4] the first major adaptive re-use project in the United States. It opened in 1964. In 1965, Benjamin Thompson and Associates renovated the lower floor of the Clock Tower, keeping the existing architectural elements, for a Design Research store.[5] The lower floors of the Clock Tower are now home to Ghirardelli Square's main chocolate shop.

In 1981, Ghirardelli Square was bought by a partnership of Capital & Counties USA and Northwestern Mutual Life.[6]

In order to preserve Ghirardelli Square for future generations, the Pioneer Woolen Mills and D. Ghirardelli Company was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.[7]

In 2008, part of the former clock tower building opened as Fairmont Heritage Place hotel. The hotel includes 53 residence-style rooms spanning four floors, and offers fractional ownership opportunities for all 53 of its hotel rooms. It is one of the few 5-star hotels in the Fisherman's Wharf area.

In 2013, Ghirardelli Square was purchased by Atlanta, Georgia–based Jamestown L.P.[8]

Design and legacy

editThe plaza is at the eastern end of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, connecting the Embarcadero waterfront promenade to the natural parkland of the Marina Green, Crissy Field and the Presidio Parkland.[9]

Lawrence Halprin's idea for Ghirardelli Square was to preserve the space within the urban setting and create an example for other U.S. cities, something which hadn't been done before. Ghirardelli Square featured many rarities at the time of its creation. For instance, Halprin designed all the street furniture and light fixtures, at a time when street furniture was not as common. Furthermore, a wheelchair ramp was put in for William Wurster, another design choice rarity for the era. Lastly, Ghirardelli's underground garage was new: rather than having the garage connect to the road, shops were put at street level in order to promote social opportunities.[10]

The cast bronze statue[11] in Ghirardelli Plaza, titled Andrea, was installed by San Francisco sculptor Ruth Asawa in 1968.[12] It features two mermaids, one of whom is nursing a merbaby, surrounded by frogs and turtles. The statue was designed to delight viewers in the wonders of the ocean and to create a connection between the square and the nearby bay. The fountain was met with condemnation from American landscape architect Lawrence Halprin who found the piece unserious and demanded its removal.[13] Many San Franciscans, especially women residents, rallied around Asawa in support of keeping the sculpture.[14]

One obstacle for the design was that Ghirardelli Square was at the foot of the Pacific Heights neighborhood. The Pacific Heights community wanted the giant Ghirardelli sign removed because of how bright it was at night. Rather than take down the sign, Halprin had it turned around to face the waterfront.[10]

After several years, a series of renovations had departed from Lawrence Halprin's original design intention, resulting in Ghirardelli Plaza becoming visually unappealing and less accessible. Pre-2017, a revitalization project was undertaken focusing on improving public access, promoting year-round activity, improving environmental sustainability, and improving the plaza's aesthetics. The project used Lawrence Halprin's design archives and worked with the City of San Francisco's Historic Preservation Commission in order to combine Halprin's original planting and design approach with local plant species. The redesign won the Northern California ASLA Merit Award for Historic Preservation.[9]

There is some disagreement about how much Halprin's repurposed site design is originally his own. The project was initially conceived by Caree and Stuart Rose, who had pushed for retail located in reused environments, and in the 1940s, activists Jean and Karl Kortum had been arguing for the preservation of the waterfront by turning it into a combined heritage and retail center.[13]

Architects

editLawrence Halprin and William Wurster were architects of Ghirardelli Square.

Current stores on the square

edit- Bank of America

- Compass

- Broadway Coffee

- Culinary Artistas

- Elizabeth W.

- Gameday VR

- Ghirardelli Chocolate Manufact

- Ghirardelli Chocolate On The Go!

- Ghirardelli Chocolate Marketplace

- Gigi & Rose

- Gigi & Rose Children

- Imperial Parking, LLC

- Jackson & Polk

- Lola of North Beach

- Mashka Jewelry

- McCormick & Kuleto's

- Palette

- Pico

- San Francisco Brewing Company

- Subpar Mini Golf + Arcade

- Succulence

- The Cheese School

- The Pub

- Unlimited Biking

- Vom Fass

- Wattle Creek Winery

- Yap Designs

See also

editGhirardelli Square.

References

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 15, 2006.

- ^ "City of San Francisco Designated Landmarks". City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ "Lawrence Halprin, who has died aged 93, was an American architect responsible for transforming the centre of San Francisco by remodelling its main street as well as a former chocolate factory at Ghirardelli Square overlooking the city's famous bay". The Telegraph. December 10, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ "Ghirardelli Square | San Francisco". Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ Janet Levy, "Design Research: Marketing 'Good design' in the 50s, 60s, and 70s", Master of Arts thesis at Parsons The New School for Design, 2004. Chapter 1 Archived 2013-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, p. 15

- ^ "Square deal? / San Francisco's historic Ghirardelli complex reportedly on the market for $30 million". May 7, 2003.

- ^ List of San Francisco Designated Landmarks No. 30

- ^ "Jamestown Properties Buys Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco". September 24, 2013.

- ^ a b HOK Design for San Francisco's Iconic Ghirardelli Square Wins ASLA Award for Historic Preservation. (2017, April 21). Retrieved April 30, 2020, from https://www.hok.com/news/2017-04/hok-plan-for-san-franciscos-iconic-ghirardelli-square-wins-asla-award-for-historic-preservation/

- ^ a b Lawrence Halprin (March 2003). "Oral History Interview Transcript" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by Charles A. Birnbaum and Tom Fox. The Cultural Landscape Foundation. [1] Archived 2017-04-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Hertz, Leba (June 26, 2013). "Fountain creates gush of interest in Ruth Asawa". SFGATE. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ "Ruth Asawa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Parscher, J. (2018, December 3). Where Credit's Due. Retrieved April 30, 2020, from https://landscapearchitecturemagazine.org/2018/11/08/where-credits-due/

- ^ Sullivan, Robert (December 29, 2013). "Ruth Asawa, the Subversively 'Domestic' Artist". The New York Times Magazine. p. 20. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 1471956890.