Gepirone, sold under the brand name Exxua, is a medication used for the treatment of major depressive disorder.[1] It is taken orally.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Exxua |

| Other names | BMY-13805; MJ-13805; ORG-13011, Gepirone hydrochloride (USAN US) |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 14–17%[1] |

| Protein binding | 72%[1] |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4[1] |

| Metabolites | 3'-OH-gepirone; 1-(2-Pyrimidinyl)piperazine[1] |

| Elimination half-life | IR: 2–3 hours ER: 5 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine: 81%[1] Feces: 13%[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

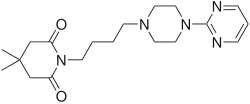

| Formula | C19H29N5O2 |

| Molar mass | 359.474 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects of gepirone include dizziness, nausea, insomnia, abdominal pain, and dyspepsia (indigestion).[1] Gepirone acts as a partial agonist of the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor.[1][2] An active metabolite of gepirone, 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine, is an α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist.[1][3] Gepirone is a member of the azapirone group of compounds.[2]

Gepirone was synthesized by Bristol-Myers Squibb in 1986 and was developed and marketed by Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals.[4] It was approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder in the United States in September 2023.[4] This came after the drug had been rejected by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) three times over two decades due to insufficient evidence of effectiveness.[5]

Medical uses

editGepirone is indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults.[1] Of 15 clinical trials of gepirone for major depressive disorder submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), three were excluded for methodological reasons, three were deemed "failed" and "uninformative", seven were deemed negative and did not demonstrate effectiveness, and two were deemed positive and did show effectiveness.[6] Two positive trials are needed for FDA drug approval, with this being the case regardless of the number of negative trials.[7] In the two positive trials of gepirone for depression, the drug significantly outperformed placebo in terms of depressive symptom reduction and showed effect sizes similar to those of other approved antidepressants.[1][8] In both trials, gepirone reduced depressive symptoms by about 2.5 points more than placebo on the 52-point Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17-item version or HAMD-17).[1] The baseline depression scores in the trials ranged from 22.7 to 24.2 in the different patient groups.[1]

Available forms

editGepirone comes in the form of extended-release tablets of the hydrochloride salt, gepirone hydrochloride, in the strengths 18.2 mg, 36.3 mg, 54.5 mg, and 72.6 mg.[1]

Specific populations

editIt is not known if gepirone is safe in women who are breastfeeding. Medications with more data in this setting may be preferred.[9]

Contraindications

editGepirone is contraindicated in people that have experienced an allergic reaction to gepirone, a corrected QT interval > 450 msec, a history of congenital long QT syndrome, use medications that strongly inhibit CYP3A4 (an enzyme involved in gepirone's metabolism), severe liver problems, or have used a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) medication within 14 days.[1]

Side effects

editSerious side effects of gepirone include QT prolongation (increases the risk of a potentially life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia called torsade de pointes), serotonin syndrome (especially in the presence of other serotonergic drugs), and activation of mania or hypomania in people with bipolar disorder. Common side effects include dizziness, nausea, insomnia, abdominal pain, and dyspepsia (indigestion).[1]

Interactions

editThe CYP3A4 inhibitors ketoconazole and verapamil strongly increase exposure to gepirone, whereas lithium, paroxetine, and warfarin have no effect on exposure to gepirone.[1] The CYP3A4 inducer rifampin profoundly decreases exposure to gepirone.[1]

Pharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

editGepirone acts as a selective partial agonist of the 5-HT1A receptor.[2] Unlike its relative buspirone, however, gepirone has greater efficacy in activating the 5-HT1A and has negligible affinity for the D2 receptor (30- to 50-fold lower in comparison to buspirone).[10] However, similarly to buspirone, gepirone metabolizes into 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine (1-PP), which is known to act as a potent antagonist of the α2-adrenergic receptor.[3]

Pharmacokinetics

editAbsorption

editThe absolute bioavailability of gepirone is 14 to 17%.[1] The time to peak concentrations of gepirone with the extended-release formulation is 6 hours.[1] When taken with a high-fat meal, the time to peak levels decreases to 3 hours.[1] A high-fat meal increases exposure to gepirone, with the effect increasing dependent on the amount of fat in the meal.[1] Peak concentrations were increased by 27% with a low-fat meal, 55% with a medium-fat meal, and 62% with a high-fat meal, while area-under-the-curve levels of gepirone were increased by 14% with a low-fat meal, 22% with a medium-fat meal, and 32 to 37% with a high-fat meal.[1] The effect was similar for the metabolites of gepirone, 1-PP and 3'-hydroxygepirone (3'-OH-gepirone).[1]

Distribution

editThe apparent volume of distribution of gepirone is approximately 94.5 L.[1] The plasma protein binding of gepirone in vitro is 72% and is independent of concentration.[1] The plasma protein binding of 3'-OH-gepirone is 59% and of 1-PP is 42%.[1]

Metabolism

editGepirone is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4.[1] Its major metabolites are 1-PP and 3'-OH-gepirone, both of which are pharmacologically active.[1] These metabolites are present in the circulation at higher concentrations than gepirone.[1]

Elimination

editWith a single oral dose of radiolabeled gepirone, 81% is recovered in urine and 13% is recovered in feces as metabolites.[1] About 60% of the gepirone is eliminated in urine within 24 hours.[1]

The terminal half-life of gepirone as the extended-release form is approximately 5 hours.[1]

Chemistry

editGepirone is a member of the azapirone group of compounds and is structurally related to buspirone, tandospirone, and other azapirones.[11]

History

editGepirone was developed by Bristol-Myers Squibb in 1986,[5] but was out-licensed to Fabre-Kramer in 1993. The FDA rejected approval for gepirone in 2002 and 2004.[5] It was submitted for the preregistration (NDA) phase again in May 2007 after adding additional information from clinical trials as the FDA required in 2009. However, in 2012 it once again failed to convince the FDA of its qualities for treating anxiety and depression.[5] In December 2015, the FDA once again gave gepirone a negative review for depression due to concerns of efficacy.[12] However, in March 2016, the FDA reversed its decision and gave gepirone ER a positive review.[13] Gepirone ER was finally approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder in the United States in September 2023.[5]

Society and culture

editNames

editThe brand name of gepirone is Exxua.[1] Former tentative brand names which were never used included Ariza, Variza, and Travivo.[4]

Research

editGepirone is under development for the treatment of decreased libido and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).[4][14][15] As of October 2023, it is in phase III clinical trials for these indications.[4] The pro-sexual effects of gepirone appear to be independent of its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects.[14][15]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am "EXXUA (gepirone) extended-release tablets, for oral use" (PDF). Mission Pharmacal Company. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Kishi T, Meltzer HY, Matsuda Y, Iwata N (August 2014). "Azapirone 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist treatment for major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Psychological Medicine. 44 (11): 2255–2269. doi:10.1017/S0033291713002857. PMID 24262766. S2CID 20830020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2019.

- ^ a b Halbreich U, Montgomery SA (1 November 2008). Pharmacotherapy for Mood, Anxiety, and Cognitive Disorders. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 375–. ISBN 978-1-58562-821-6.

- ^ a b c d e "Gepirone - Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals". AdisInsight. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Becker Z (28 September 2023). "Decades long regulatory odyssey ends with FDA nod for Fabre-Kramer's depression med Exxua". Fierce Pharma.

- ^ Firth S (30 November 2015). "Controversial Antidepressant Comes Up for FDA OK -- Again". MedPage Today.

- ^ Kirsch I (2014). "Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect". Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 222 (3): 128–134. doi:10.1027/2151-2604/a000176. PMC 4172306. PMID 25279271.

- ^ "FDA Rules Favorably On Efficacy Of Travivo (Gepirone ER) For Treatment Of Major Depressive Disorder". Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Cision PR Newswire. 17 March 2016.

- ^ "Gepirone". Drugs and Lactation Database. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2006. PMID 37856644. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (2009). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 494–. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9.

- ^ Kaur Gill A, Bansal Y, Bhandari R, Kaur S, Kaur J, Singh R, et al. (July 2019). "Gepirone hydrochloride: a novel antidepressant with 5-HT1A agonistic properties". Drugs of Today. 55 (7): 423–437. doi:10.1358/dot.2019.55.7.2958474. PMID 31347611. S2CID 198911377.

- ^ "Gepirone ER". Adis Insight. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ "FDA Rules Favorably On Efficacy Of Travivo (Gepirone ER) For Treatment Of Major Depressive Disorder" (Press release). 17 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ a b Fabre LF, Brown CS, Smith LC, Derogatis LR (May 2011). "Gepirone-ER treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) associated with depression in women". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (5): 1411–1419. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02216.x. PMID 21324094.

- ^ a b Fabre LF, Clayton AH, Smith LC, Goldstein I, Derogatis LR (March 2012). "The effect of gepirone-ER in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in depressed men". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9 (3): 821–829. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02624.x. PMID 22240272.