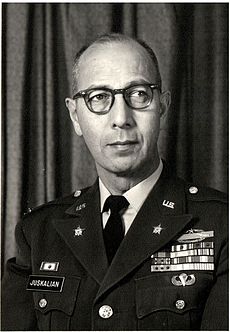

George Juskalian (Armenian: Գեւորգ Ժուսգալեան; June 7, 1914 – July 4, 2010) was a decorated Colonel of the United States Army who served for over three decades and fought in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.[1] Following graduation from Boston University, Juskalian entered the army as a second lieutenant in June 1936. During World War II, he served with the infantry during the North African Campaign and took part in Operation Torch. At the Battle of the Kasserine Pass, he was captured by German troops and became a prisoner of war (POW) for twenty-seven months. During the Korean War he commanded an infantry battalion. He was then stationed in Tehran where he acted an advisor to the Imperial Iranian Army throughout 1957 and 1958. During the Vietnam War, Juskalian once again undertook advisory duties, working with the South Vietnamese Army between 1963 and 1964, before serving as the MACV inspector general under General William Westmoreland.

George Juskalian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 7, 1914 Fitchburg, Massachusetts |

| Died | July 4, 2010 (aged 96) Centreville, Virginia |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1936–1938 1939–1967 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | 339066 |

| Battles / wars | World War II Korean War Vietnam War |

| Awards | Silver Star (2) Legion of Merit Bronze Star (4) Air Medal |

| Spouse(s) | Beatrice MacDougall Lucine Barsoumian |

| Other work |

|

Juskalian retired as a colonel in 1967 and is one of the most decorated Armenian-Americans to serve in the United States Army. His awards include two Combat Infantryman Badges, two Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit, four Bronze Stars and the Air Medal.[1][2] He received the Nerses Shnorali Medal from the Catholicos of All Armenians in 1988. The post office in his home town of Centreville, Virginia, has been named the "Colonel George Juskalian Post Office Building" in his honor.

Early life

editGeorge Juskalian was born in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, on June 7, 1914, the youngest son of Armenian parents Kevork Juskalian (1861–1938) and Maritza Ferrahian (1876–1960).[3] George's father, Kevork, was from Kharpert, Ottoman Empire, and his mother Maritza was from Arapkir, Ottoman Empire.[3]

Kevork Juskalian was among the earliest graduates of the Euphrates College in Kharpert, completing his studies around 1881.[4] He served as a minor official of the local Turkish government in Mezire, a village near Kharpert. He was then invited to work in the Persian consulate in Mezire until he was recalled by the Turkish government to serve as supervisor of eleven villages in the region of Kharpert. Kevork Juskalian felt that there was no secure future for him in Ottoman Turkey and subsequently fled to the United States with his family, arriving at Ellis Island on November 15, 1887. Consequently, the Juskalian family became some of the first Armenians to come to the United States.[4] Kevork found a job at the Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Works in Worcester, Massachusetts. He was instrumental in the establishment of the Armenian Church of Our Savior on January 18, 1891.[4]

In 1893, Kevork returned to Kharpert and married Maritza Ferrahian, daughter of Krikor and Yeghisapet (Yesayan) Ferrahian. Due to the Hamidian Massacres, Kevork and Maritza returned to the United States and Kevork rejoined the Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Works company.[5]

Juskalian, who grew up in Fitchburg, attended the local schools and graduated from Fitchburg High School in 1932. He continued his education at Boston University, graduating in 1936 with a bachelor's degree in science, journalism.[6]

Military service

editWhile studying at Boston University, Juskalian undertook military training as part of the Reserve Officers Training Corps.[3] On graduation, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Army,[3] and in June 1936, was assigned as an administrative officer of a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Brewster, Massachusetts, where he helped build a national park.[7][6]

After leaving active service, Juskalian had intended to study law at the American University in Washington, D.C., but when his father died in 1938, he gave up this plan and returned to Fitchburg to reunite with his mother and assist his brother-in-law's dry-cleaning business.[7] That year, after passing a government exam, Juskalian became a fingerprint classifier for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and took part in the search for John Dillinger, who was on the "Top 10 Most Wanted" list.[7] He then volunteered for active service in 1939.[7]

Juskalian was called to active duty at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and was promoted to the rank as first lieutenant in November 1940.[7] Juskalian was given command of a 200-man company after the reorganization of the 1st Infantry Division.[7] In February 1942, Juskalian was promoted to captain and was sent to Camp Blanding, Florida, before moving to Fort Benning, Georgia and then Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Pennsylvania, for additional training and combat readiness evaluation.[6] In August 1942, Juskalian boarded the RMS Queen Mary, and along with the other 15,000 soldiers of the 1st Infantry Division, was shipped to Europe.[7]

World War II

editNorth African Campaign

editThe soldiers of the 1st Infantry Division are believed to be among the first American troops shipped out to the European theater during the war.[1] The division landed near Glasgow, Scotland, then proceeded to a British Army base near London to continue training.[7] Juskalian, who became the assistant plans and operations officer on the regimental staff, went to Inveraray, Scotland, to train for the North African Campaign.[7]

Juskalian then took part in Operation Torch as part of the 1st Infantry Division's 26th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Theodore Roosevelt Jr.[7][8] The Allies, who had organized three amphibious task forces, aimed to seize key ports and airfields in Morocco and Algeria while simultaneously targeting Casablanca, Oran and Algiers. Juskalian's unit was part of the task force that invaded through the port of Oran.[7]

Landing in Oran on November 8, 1942, the 1st Infantry Division's primary objective was to confront the German Afrika Korps commanded by Erwin Rommel, while its secondary objective was to support Bernard Law Montgomery's advance against the Italian forces.[9] Eventually, the 1st Infantry Division broke through the German resistance and scaled Mount Djebel.[7] Oran fell to the Allies on November 10 and Juskalian's unit advanced east into Tunisia, reaching the Algeria–Tunisia border by January 15, 1943. There, the task force met resistance from German and Italian troops.[7]

German prisoner of war

editAs the fighting continued into the Makthar Valley, Juskalian was assigned to the 26th Infantry Regiment's headquarters.[7] When attempting to save the life of a fellow soldier following heavy fighting, he was captured by German troops at Kasserine Pass in Tunisia on January 28.[1][10][11] Juskalian described his capture as follows: "One of our intelligence officers had gone out to check on the situation, and word came back that he'd been wounded and was out there somewhere. So another officer and I went out in a Jeep and found him, but he was dead. Then we came under fire, so we couldn't drag him out of there."[7] After telling the driver to return to the command post, Juskalian investigated the conditions of the other U.S. soldiers. "I thought they were all right because we hadn't heard anything from them, but they'd been overrun by the Germans."[7] Having lost his glasses, Juskalian could not distinguish the soldiers that were approaching him from 50 feet (15 m) away. The soldiers were Germans and took him prisoner. Juskalian said about his capture, "I was irritated with myself for being so foolhardy, I shouldn't have been there."[7] Juskalian later learned, while still a prisoner of war (POW), that he had been awarded the Silver Star for his rescue attempt.[12] After his first two days of being a POW, he was promoted to major.[9][11]

Oflag IX-A/Z in Rotenburg, Germany

editJuskalian spent the next twenty-seven months as a POW and was held in various camps in Italy, Poland and Germany.[1][13] After being interrogated in Kairouan, he was sent to Tunis and flown to Naples. The planes flew at a low altitude as Juskalian described: "They flew about 100 feet above the Mediterranean because they were afraid that, if they flew higher, the American fighter planes—not knowing POWs were inside—would see us and shoot us down."[7] The POWs were sent to Oflag IX-A/Z British POW camp in Rotenburg an der Fulda where they remained until June 6, 1943, when they were transferred to Oflag 64 in Szubin, Poland.[7][14]

The British POWs provided the Americans with necessary advice regarding the camp life and shared rations and clothing sent by the British Red Cross.[15] The British, who were in the process of digging an escape tunnel, requested help from the Americans. Juskalian would later describe the operation: "I volunteered, although I have had claustrophobia ever since a boyhood friend shut me up in a wood bin for a prank. When I look back at it, I wonder how I did it. Some nights when I think about it, I break out in a cold sweat. Somehow, I was able to summon up the will to do it. The tunnel was already some 80 to 100 feet long. It extended underground beyond the barbed wire fence, but those in charge wanted to lengthen it so that the opening would come out below ground level on the steep side near the bank of the Fulda River. In that way when the tunnel was broken open, the escapees could not be seen by the guards in the towers."[15]

The tunnel was about 3 feet (1 m) high by 3 feet (1 m) wide. Lighting in the tunnel was provided by makeshift candles. The prisoners used improvised digging tools and shovels that were constructed from British biscuit cans and their handles made from the wooden slats of their beds.[7] The tins were also used to create a pipe for fresh air to funnel through the tunnel with the assistance of a hand-cranked fan at the entrance of the tunnel.[7] A sled, made of wooden slats with a tine base to make it slide easily over the earthen tunnel floor, was used to haul the sandbags. Juskalian described the method that was used to dispose the sand: "The method used to conceal the sand was ingenious. The sand was poured into burlap bags made surreptitiously from Red Cross parcel wrappings then passed rapidly along a makeshift fire brigade line through the building and up into the attic. There it was dumped between the outer and inner walls where there was a wide space for insulation. Literally tons of sand could be disposed of there before the space would be filled."[15]

Before the tunnel had been completed, the American POWs were transferred to Oflag 64 in Szubin, Poland. Juskalian estimated that if the tunnel had been dug for another 100 feet, it would reach its destination at the bank of the Fulda River. Two American POWs pretended to be sick in order to remain in the Rotenburg camp and to continue working on the tunnel and ultimately escape. The two Americans, who eventually rejoined the rest of the American POWs in Oflag 64, relayed the news that the tunnel had been discovered by the German guards who had learned of its existence after planting a spy among the POWs.[16]

Oflag 64 in Szubin, Poland

editJuskalian spent nineteen-and-a-half of his twenty-seven months imprisonment in Oflag 64.[14] The POWs in the camp undertook various leisure activities including staging plays, playing music, reading, athletics, and learning languages.[14] While there, Juskalian became an editor of a monthly newspaper that was published with the assistance of a guard who owned a local printing shop.[14] The newspaper featured "stories from home, cartoons, pictures of pin-up girls and girlfriends and articles about camp sports and activities".[14]

In June 1944 the American POWs held a party on the first anniversary of being in the camp.[12] The party coincided with the Normandy landings, and the Germans suspected that the American POWs had purposely planned the party because they had prior knowledge of the Allied invasion.[12] The commandant of Oflag 64 called higher headquarters for advice and assistance.[17] Eventually the German Gestapo searched the Americans' rooms for evidence of outside communication. However, Juskalian shared one of the cigars his brother-in-law, Hagop Chiknavorian, had given him, with the officer undertaking the search who soon became "distracted and softened".[17]

Oflag XIII B in Hammelburg, Germany

editOn January 21, 1945, the German troops and their POWs moved westward into Germany to avoid the Soviet advance from the east.[18] Juskalian and other American POWs were transferred to Parchim, northeast of Berlin, on March 1, 1945. Over the course of 48 days, the POWs traveled 350 miles (560 km) from Parchim to Oflag XIII-B in Hammelburg in box cars which, according to Juskalian, were "packed like sardines."[9] During his time in Hammelburg, Juskalian met another Armenian POW, Captain Peter Mirakian of Philadelphia.[9] Together, the two Armenian Americans discovered that one of the Soviet POWs was also an Armenian.[12] Mirakian and Juskalian surreptitiously gave him food from their limited rations.[12]

The camp at Hammelburg held many American prisoners including George S. Patton's son-in-law, Lieutenant Colonel John K. Waters.[18] Attempting to rescue Waters, a military task force from the 4th Armored Division was sent to liberate the camp.[18] When the task force arrived, the German guards fled the camp, but the task force did not have enough vehicles to evacuate all POWs in the camp. Mirakian and Juskalian escaped through an opening in the compound fence and ran towards Frankfurt hoping to reach the American lines there, but a German patrol captured them, and they were immediately sent to Nuremberg.[9] Juskalian later remarked: "We were tired and depressed but thankful to be alive."[7]

The bombs rained down upon us with the terrifying roar of a thousand locomotives. We hit the ground. In the split second that followed, my thoughts were of my mother. There she was at home waiting for my return. With Allied victory assured, she had every expectation that I would be back soon. The end of the war was at hand. And to be killed now, and by one's own planes! How horrible; how ironic. There would be two deaths, not one: mine and my mother's.

—George Juskalian[19]

While Juskalian was held in Nuremberg, the Americans began their bombardment of the city. He describes the moment in his own words: "We were cheering, and our guards were getting irritated, but the bombs came down on us, too, and I was sure we were going to get it. About 30 of us were killed. I was thinking of my mother and how ironic it would be to be killed at the end of the war—and by your own aircraft."[18]

After surviving the bombardment, the POWs were resettled in a camp near Munich. The Germans gave them the opportunity to return to Nuremberg as wounded soldiers to obtain treatment; the POWs agreed because it was closer to the American lines.[18] On April 17, American troops secured Nuremberg and subsequently freed the POWs.[9][12] Juskalian described the event: "When the Germans tried to see if we were really wounded, the British erected a sign on the gate saying 'Plague', and that kept them out, three or four days later, the 45th U.S. Infantry Division overran Nuremberg and we were liberated."[18]

Juskalian was flown to Paris, France, where he presented himself at a military post and requested financial assistance.[7][12] However, he did not have official identification and was refused. An officer, who knew George's older brother Richard (Dikran), who lived in Watertown, overheard him and recognized the last name Juskalian. George confirmed that Richard was his brother, and he was then given all the provisions he needed.[12]

Post World War II

editUpon returning to the United States after the war, Juskalian had an appointment with the regular army where he was ultimately promoted to lieutenant colonel.[9] He reported to the Pentagon for duty in the Office of the Secretary of the Army Chief of Staff from 1945–1948.[3][9] In the Pentagon, Juskalian was assigned as an assistant secretary in the Secretariat of the War Department and was a secretary to Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Chief of Staff of the Army.[20] His responsibilities included supporting the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Combined Chiefs of Staff of the British and Americans and preparing briefs for Eisenhower.[14][21] After his tour of duty at the Pentagon, he attended the Army's Command and General Staff College's regular ten-month course at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, from 1948 to 1949.[22] His next assignment was with the staff and faculty of the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, where he remained from 1949 until the summer of 1952.[23] While at the school, he took airborne training and became a qualified parachutist.[23]

Juskalian was then assigned to Alaska as commandant of the Arctic Warfare School.[23] Still embittered by the memory of having spent most of World War II as a POW, he requested his orders be changed from Alaska to Korea where United States forces were engaged in combat operations as part of the United Nations forces committed to Korean War.[14] His request was approved and in the summer of 1952 he was sent to the combat zone.[23]

Korean War

editJuskalian was assigned as a battalion commander from 1952 to 1953. In 1953, he commanded the 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division.[3][24] In the final winter of the war the Chinese attempted to overcome the United Nations' main line of resistance and capture a series of hills. Juskalian's battalion was assigned to carry out a counterattack on a 300-foot high hill known as "Old Baldy" during an action that later became known as the Battle of Old Baldy.[25] When the Chinese offensive came to a halt, Juskalian reorganized the forces under his command and sent both A and B Companies, under First Lieutenant Jack L. Conn, on a second attack[24] to retake the hill, but they regained only a quarter of it.[24] On March 25 Juskalian ordered C Company, under First Lieutenant Robert C. Gutner, to attack from the northeast, but enemy forces halted their advance.[24] Many members of C Company were trapped on the right flank of Old Baldy, and Juskalian requested tank support to demolish the Chinese bunkers to free 30 to 40 troops of the company.[24] On the night of March 26, Juskalian received orders from Regimental Commander Colonel William B. Kern to withdraw his forces.[25]

To the east of Old Baldy heavy fighting took place around Pork Chop Hill, which was later made famous by the movie Pork Chop Hill starring actor Gregory Peck.[9] The Chinese force grew and became numerically superior to the Americans,[9] and Juskalian was ordered to withdraw. Due to his efforts and the successful withdrawal of troops, he was awarded a second Silver Star for gallantry.[9] At the end of the war in June 1953, he was transferred to the Eighth Army Headquarters in Seoul where he assisted in the prisoner of war exchange that took place at Panmunjom.[26]

Upon his return to the U.S. in October 1953 he is sent to the Armed Forces Staff College as a student. Upon graduating in July 1954 he was assigned to the G-3 Section of the Department of the Army. Juskalian becomes Executive Officer of the 74th Regimental Combat Team, Ft Devens October 1955 and probably remains with the 74th RCT till it's inactivation in September 1956.

Missions in Iran, New York, and France

editJuskalian was assigned as a logistics officer to the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) in Tehran, Iran in 1957.[27] He then became chief of the Training Division of the Iranian First Army and was promoted to full colonel.[9][27] As principal logistics officer, Juskalian supervised the U.S. Army officers advising the Iranian Army general officers serving as technical service department chiefs.[28] Additionally, his office was responsible for managing the annual input of U.S. military material and construction to the Iranian armed forces.[9] During his time in Iran, Juskalian met many Armenians in Tehran, a number of whom he kept in touch with for the rest of his life.[9]

After his mission in Iran in 1957–1958, Juskalian visited Kharpert, his father's birthplace. In an article he later wrote about the trip entitled "Harput Revisited", which appeared in the April 1959 issue of the Armenian Review,[29] Juskalian wrote: "I tried in vain to locate my parents' home. Mezireh, as a community, was alive and well. Harput (Kharpert), on the other hand was dead, a bleak landscape of debris where once proudly stood a college, schools, churches, shops and homes. There was not even a grave over which to weep and pray for the souls of those from whom I came."[30]

After completing his duties in Iran, Juskalian assumed the role of chief of operations and training at the headquarters of the First Army that commanded all U.S. Army installations in New England, New York and New Jersey.[30] His posting in New York was cut short by the Berlin Crisis of 1961, and Juskalian was sent to France to join the 1st Logistical Command. When the 1st Logistical Command was merged with the 4th Logistical Command at Verdun, Juskalian was transferred to this command, serving as the G-3 chief of plans, operations and training.[31]

Vietnam War

editAfter his tours of duty in New York and France, Juskalian volunteered to fight in Vietnam in late spring of 1963.[31] He arrived in Saigon in August 1963 and took up a posting as deputy senior advisor to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam's IV Corps stationed in the Mekong Delta.[14] After six months, Jukalian was assigned to the headquarters of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) to serve as the MACV inspector general under General William Westmoreland, the MACV commander.[14][27] As part of his duties, he traveled throughout South Vietnam on inspection visits to many military installations. In the transient officers quarters at Danang, he found an ashtray from George Mardikian's Omar Khayyam restaurant in San Francisco and kept it as a souvenir for the rest of his life.[32] For his service in the Vietnam War, Juskalian was awarded an Air Medal and a Bronze Star.[14]

Juskalian returned to the United States in August 1964 and was posted to headquarters of Military District of Washington (MDW) as Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Training, his last Army assignment before retirement.[33] During his three years at MDW, he served as chairman of the Joint Military Executive Committee that was chiefly responsible for planning and carrying out all arrangements for the participation of military services in the inauguration of President Lyndon B. Johnson in January 1965.[34]

Post-retirement from the army

editJuskalian retired from the army on April 30, 1967, and was awarded the Legion of Merit.[34] After his retirement, he settled in Arlington, Virginia.[18] Juskalian worked as the graduate admissions director at the Southeastern University in Washington D.C. for eight years and attained a master's degree in business and public administration with honors in 1977 at the age of sixty.[35]

He was a member of many veterans' organizations including the American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Disabled American Veterans, the American Ex-Prisoners of War, the Retired Officers Association, and the 1st Infantry Division Association for the Uniformed Services (NAUS).[36] He served for a term as first vice president of NAUS and was the commander of the Northern Virginia Chapter of the American Ex-Prisoners of War.[36]

In 1982 Juskalian was appointed for a three-year term to the Veterans Administration Advisory Committee for Former Prisoners of War.[36] Whenever possible, he attended annual reunions with former Oflag 64 POWs and the annual national conventions of the American ex-POW organization.[37] He was appointed to the Editorial Advisory Board of the newly established Washington Times daily newspaper in 1983.[38]

Community service

editJuskalian was a prominent figure in the Armenian community. He served at the local St. Mary's Armenian Apostolic Church and the Diocesan Council of the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America.[3] He served on the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America, and subsequently for a ten-year term on its Board of Trustees.[38] He was also a member of the Armenian General Benevolent Union's Central Committee of America and the Armenian Assembly of America.[3]

He helped organize a memorial service for Armenian American veterans at the Arlington National Cemetery on May 21, 1978, where the graves of forty-nine Armenian American veterans, spanning the period from the Spanish–American War to the Vietnam War, were decorated with carnations.[36] Juskalian also volunteered in local schools. He continuously stressed the importance of public service and shared many of his experiences with students.[18]

Personal life

editOn August 31, 1951, Juskalian married Beatrice MacDougall, the widow of Lieutenant Jack W. Kirk, one of his first company commanders.[39][40] The marriage ended in divorce in 1958. In 1970, he married his second wife, Lucine Barsoumian, an Armenian from Aleppo, Syria.[35] They had a son named Kevork and a daughter named Elissa. Kevork graduated from George Mason University in May 1996 with a master's degree in international transactions and was later commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Regular Army.[41] Gregory, a son by his previous marriage with Beatrice MacDougall, lives in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.[41] George Juskalian was also the cousin of Medal of Honor recipient Ernest Dervishian who received the award while serving in the U.S. Army during World War II.[42]

After his second marriage, Juskalian and his wife visited many countries including Lebanon, Egypt, Italy, France, Spain and his homeland of Armenia.[36] In 1989, Juskalian along with his family moved to Centreville, Virginia, where he remained the rest of his life.[35]

Juskalian died on July 4, 2010; funeral processions were held at the St. Mary's Armenian Apostolic Church in Washington D.C. He is buried in the Prisoner of War Section of the Arlington National Cemetery.[13]

Recognition

editIn 1988 Juskalian was awarded the St. Nerses Shnorhali Award and Lifetime Achievement and Pastor's Recognition Award bestowed by Vasken I, Catholicos of All Armenians for his dedication to the Armenian community.[43][44]

Juskalian was featured in the documentary series Americans At War by the U.S. Naval Institute.[45] Each episode of the documentary series features a U.S. veteran recounting a defining moment from his or her time in the armed services.

During a ceremony marking the seventy-fourth anniversary of Washington's Armenian community, Armenia's ambassador to the United States Doctor Tatoul Markarian, expressed his appreciation of Colonel Juskalian's many contributions to the Armenian community, and congratulated him for his lifetime achievements.[46]

On April 23, 2007, the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors recognized Juskalian for "heroism and honorable service" to the United States.[3]

Following Juskalian's death on July 4, 2010, Virginia Senator Jim Webb wrote: "It is my understanding that Colonel Juskalian was one of the most highly decorated Armenian-American Veterans to serve in the United States Army. I am sure his dedication to serving the Armenian-American community will be missed and his contribution will always be remembered."[13]

On May 21, 2011, President Barack Obama signed House Resolution 6392 of the 2nd Session of the 111th Congress which designated the post office on 5003 Westfields Boulevard in Centreville, Virginia, as the "Colonel George Juskalian Post Office Building".[47][48] The renaming ceremony was celebrated at the post office on the same day and was attended by friends, family, politicians, former POWs, veterans, and members of the Armenian community.[35] Attendees included U.S. Congressman Frank Wolf, Virginia Delegate Jim LeMunyon and member of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors Michael Frey.[1][35] During the ceremony, letters of appreciation were read from former Senator John Warner and Presidential candidate Bob Dole.[3]

Military awards and decorations

editJuskalian's military awards and decorations include:[49]

| Uniform left side: Combat Infantryman Badge with star | |||

| Silver Star Medal with oak leaf cluster | |||

| Legion of Merit | Bronze Star Medal with 3 oak leaf clusters |

Air Medal | Army Commendation Medal |

| Prisoner of War Medal | American Defense Service Medal | American Campaign Medal | Europe-Africa-Middle East Campaign Medal with 2 campaign stars and Arrowhead device |

| World War II Victory Medal | National Defense Service Medal with 1 service star |

Korean Service Medal with 3 campaign stars |

Vietnam Service Medal with 1 campaign star |

| Armed Forces Reserve Medal | United Nations Korea Medal | Vietnam Campaign Medal | Republic of Korea War Service Medal |

| Parachutist Badge | |||

| Uniform right side: Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation |

Silver Star citation

editThe citation for Juskalian's second Silver Star published in General Orders 41, Headquarters 7th Infantry Division, 18 July 1953 reads:

Lieutenant Colonel George Juskalian, 032371, Infantry, United States Army, a member of Headquarters, 1st Battalion, 32d Infantry, distinguished himself by gallantry in action near Chorwon, Korea. During the period 24 March 1953 to 26 March 1953, Colonel Juskalian led his battalion in a counterattack against strong enemy positions. Colonel Juskalian advanced with the foremost elements of his battalion during the entire conflict. During the attack the battalion encountered a mine field blocking the only route of approach, but Col. Juskalian—with complete disregard for his personal safety—placed himself at the front of his unit and led them through the field. Often exposing himself to the enemy, [he] moved from position to position. Colonel Juskalian remained on the position to direct the operations and finally led the last element of his command from his position. The gallantry [he] displayed is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service. Entered the Federal service from Massachusetts.[14][26]

Published works

editJuskalian wrote for journals concerning Armenian or military topics. Some of his writings include:

- "Harput Revisited", Armenian Review (Spring, April 1959). Recounts his visit to his father's native village of Harput, in Turkey.

- "Why Didn't They Shoot More?", Army Combat Forces Journal (September 1954), V, No. 2, p. 35. Depicts his battles during the Korean War.

- "A Journey to New Julfa", Armenian Review (Spring, May 1960). Describes his visit to New Julfa, an Armenian populated town in Iran and concludes that the town has lost most of its importance and vitality.

- "East is East and West is West", Ararat Quarterly (Fall 1973), Vol. XIII, No. 4, p. 19. Recounts his visit with the Sagoyan family, an Armenian family that received him while he was in Japan.

- "The Life You Save", Ararat Quarterly (Spring 1988), Vol. XXIV, No. 2, p. 48.

References

edit- Sources

- ^ a b c d e f Vittori, Elizabeth (May 24, 2011). "War Hero Honored at Post Office Dedication". CentreVillePatch.

- ^ Dan Scandling (November 29, 2010). "House Honors Deceased Veteran from Centreville". Targeted News Service. Washington, D.C.

After leaving the military as one of the highest ranking Armenian-Americans, Colonel Juskalian continued to serve the community by volunteering in local schools and sharing his message of the importance of public service in appreciation for the freedoms enjoyed by all Americans.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Melkonian, Hovsep M. (June 3, 2011). "US Government Honors the Late Col. George Juskalian by Naming Post Office in His Honor". Armenian Mirror-Spectator. Washington D.C.

- ^ a b c Demirjian 1996, p. 340.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 341.

- ^ a b c Demirjian 1996, p. 342.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Recollections of a War Veteran". The Virginia Connection. June 9, 2004.

- ^ "Society of 1st ID Mark Operation Torch". Association of the United States Army. January 1, 2002. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013.

Standing in front of the 1st Infantry Division Monument after the commemoration ceremony ended, George Juskalian, an Operation Torch veteran with the 1st Infantry Division's 26th Infantry Regiment, told his wife and daughter why it was important that he attended.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mooradian, Moorad (November 30, 1991). "Military: Arms and the Man". Armenian International Magazine. 2 (10). Glendale, CA. ISSN 1050-3471.

- ^ "N.E. Men Win Citations For Heroic Acts". Christian Science Monitor. August 5, 1943.

- ^ a b Armenian General Benevolent Union (1951). Armenian-American veterans of World War II. Published and compiled by "Our Boys" Committee. p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Papazian, Iris (December 10, 1994). "Military Hero Reminisces at St. Mary's/Ararat Foundation Lecture". Armenian Reporter International. 28 (10). Paramus, NJ. ISSN 1074-1453.

- ^ a b c Melkonian, Hovsep (July 27, 2010). "Farewell to a patriot and an American hero". The Armenian Reporter. Archived from the original on August 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Recollections of a War Veteran Part II". The Virginia Connection. June 16, 2004.

- ^ a b c Demirjian 1996, p. 347.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 350.

- ^ a b Demirjian 1996, p. 353.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hobbs, Bonnie (May 26 – June 1, 2011). "George Juskalian, in His Own Words" (PDF). Centre View. p. 4.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 358.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 360.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, pp. 360–61.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 361.

- ^ a b c d Demirjian 1996, p. 363.

- ^ a b c d e Hermes 1966, p. 394.

- ^ a b Hermes 1966, p. 395.

- ^ a b Demirjian 1996, p. 368.

- ^ a b c "Military Service". Ararat Quarterly. 18. Armenian General Benevolent Union: 103. 1977.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 370.

- ^ Juskalian, George (Spring 1959). "Harput Revisited". Armenian Review. 12 (1). Hairenik Association: 3–14.

- ^ a b Demirjian 1996, p. 372.

- ^ a b Demirjian 1996, p. 373.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 375.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 376.

- ^ a b Demirjian 1996, p. 377.

- ^ a b c d e Hobbs, Bonnie (May 26 – June 1, 2011). "Post Office Dedicated in Juskalian's Honor" (PDF). CentreView. p. 1/4.

- ^ a b c d e Demirjian 1996, p. 378.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, pp. 378–79.

- ^ a b Demirjian 1996, p. 379.

- ^ "Beatrice Juskalian". The Berkshire Eagle. March 29, 2011.

There she met and married Lt. Jack W. Kirk who was subsequently killed in action in Africa. Kirk was the recipient of two Silver Stars and the Purple Heart. She later married Colonel George Juskalian who passed away July 4, 2010. Juskalian was Kirk's first company commander and was also awarded two Silver Stars and the Legion of Merit for service during World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. They were divorced in 1958.

- ^ "Juskalian-Kirk". Army, Navy, Air Force Journal. 89 (1–26). Army and Navy Journal Incorporated: 56. 1951. ISSN 0196-3597.

- ^ a b Demirjian 1996, p. 380.

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 359.

- ^ "The Community Forum: "What Will Be The Future Of The Armenian Church In America?"". Armenian Reporter International. 30 (11). December 14, 1996. ISSN 1074-1453.

- ^ "Candle-lighting Marks 74th Anniversary of Washington's Armenian Community". Armenian Reporter. 39 (7). Paramus, NJ. November 11, 2006.

Col. George Juskalian – one of the seven recipients of the St. Nerses Shnorhali Medal among St. Mary's parishioners, bestowed by the Catholicos of All Armenians – received a "Lifetime Achievement and Pastor's Recognition Award."

- ^ Vittori, Elizabeth (February 2, 2011). "Juskalian, Decorated Local Veteran, Honored". Archived from the original on June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Candle-lighting Marks 74th Anniversary of Washington's Armenian Community". Armenian Reporter. 39 (7). Paramus, NJ. November 11, 2006.

- ^ "H.R. 6392" (PDF). United States Government. November 29, 2010.

- ^ "Statement by the Press Secretary". whitehouse.gov. Washington D.C. January 4, 2011 – via National Archives.

On Tuesday, January 04, 2011, the President signed into law: H.R. 6392, which designates a facility of the United States Postal Service as the Colonel George Juskalian Post Office Building

- ^ Demirjian 1996, p. 338.

- Bibliography

- Demirjian, Richard N. (1996). Triumph and Glory: Armenian World War II Heroes. Moraga, Calif.: Ararat Heritage Publ. ISBN 9780962294518.

- Hermes, Walter G. (1966). Truce Tent and Fighting Front (40, reprint ed.). Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160872938.