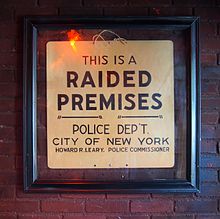

Gayola was a type of bribe used by American police departments against gay bars in the post-war era. Liquor laws prevented bars from knowingly selling alcoholic beverages to gay patrons, so police departments commonly demanded payoffs from gay bar owners as a way to prevent shutdowns and raids.

San Francisco

editPreceding the Scandal

editAccording to historian Christopher Agee, the San Francisco Police Department in the 1950s "maintained a decentralized organizational structure that gave patrol officers great autonomy in their daily activities. Police leaders prioritized their own political power over professional policing, and they therefore refused to either coordinate their policies across station lines or add the supervisory positions needed to monitor the officers on the beat."[1] As a result, policing in the city was subjective and disproportionately targeted the city's black and gay populations.

The 1951 California Supreme Court case Stoumen v. Reilly found bars and establishments could legally cater to homosexual clientele. The majority opinion ruled in favor of the Black Cat Bar, a popular bohemian and gay hangout. Phil S. Gibson wrote, "Unlike evidence that an establishment is reputed to be a house of prostitution, which means a place where prostitution is practiced and thus necessarily implies the doing of illegal or immoral acts on the premises, testimony that a restaurant and bar is reputed to be a meeting place for a certain class of persons contains no such implication."[2]

Regardless of the court's decision, the San Francisco Police Department's officers continued to demand payments from gay bar owners in order for them to avoid raids. Bob Ross, who would go on to found the Tavern Guild, an organization which helped dismantle the Gayola system in San Francisco,[3] was quoted by Christopher Agee, saying:

[Upon entering, the police officer asked,] "Hi Bob, are you the manager?" And I'd say, "Why yes." "Hi, I'm Lieutenant So-and-so." "You don't say, Lieutenant So-and-so." "Yes, the San Francisco Police Department." And right away you'd go "Oh shit." You know, "What are we up to now?" And the first time he came in he was soliciting for the . . . Police Athletic League. And I said, "Oh." I said, "I just sent them $25 or something." And he said, "Oh." He said, "This is actually the Police Officer's Retirement League section of the Police Athletic League." I said, "I never heard of that." He said, "You will; let me show you." And I said, "What do you need, $100?" He says, "No, it's gonna be $500 a month." And he says, "The captain'll be by to collect it next Tuesday at 7:30." That's how brazen they were. The captain walked in at 7:30 to collect his money."[1]

According to Ross, he also needed to buy dinner for the captain and provide him a female prostitute.

The Gayola Scandal

editThe Aftermath of the Vallerga v. Dept. Alcoholic Bev. Control bolstered the confidence of San Francisco gay bars leading to the Gayola Scandal. The Gayola Scandal refers to cops extortion and taking of bribes from gay bar owners. This scandal went to the courts in 1960 and originated directly from the Vallerga case.[4] The scandal began after a liquor licensor was caught extorting money from the Market Street Bar, they were arrested upon leaving with $150 in bribes taken from the owner.[5] The trial of the licenser went by with little news coverage and was acquitted of bribery charges yet guilty of misdemeanor charges for accepting gratuities.[4][5] Following this trial 7 beat cops were arrested and tried for bribery. All involved were suspended and then fired.[6]

This corruption was allowed due to SFPD's decentralized structure. In 1950s' San Francisco, district station captains held substantial political power. Police officers aided conservative politicians in the city, "allowing thugs to intimidate voters in precincts with large black or liberal voting populations."[1] As a result, there was little incentive on the part of downtown elites to demand substantial police reform against corruption, and even if they were so inclined, it would have proven difficult, as the Gayola system was largely operating at the ground level, rather than a high brass operation. In his historical analysis of the period, Agee writes, "As the only officers who left their desks and monitored the patrolmen on the streets, the department's two hundred sergeants held the most policing power in the SFPD. It was therefore the SFPD's two hundred sergeants who exerted the most control over the department's gay bar policies."[1]

The Gayola payments were made from bar owners to the police in what the police referred to as gratuities [5] instead of bribes. The media's reporting at the time, the San Francisco Chronicler and Examiner the main two media outlets following the trials, portrayed the scandal in line with the police's recounting of events. The polices claim as depicted in newspapers and their own briefings was that they were being paid off by the gay bars.[5][7] This was widely reported during the Gayola Scandal trials where the police claimed in court that it was "all a plot by the bar owners to discredit the police."[6] 7 policemen were arrested on bribery charges and 6 were acquitted. One officer was convicted and put in jail on shakedown charges while still acquitted on bribery.[5][6] This officer was caught by Police chief Al Nedler who worked with gay bar owners to indict his own officers. He had the owner of an Embarcadero bar use a wireless taping device to catch the extortion of the gay bar owner in the process[6] in the end it did not lead to a conviction.

Serious changes would not occur until the early-1960s, when the "gayola scandal" raised public awareness of this practice. A group of gay bar owners revealed the SFPD's practice of extortion, and this made front-page news. Mayor George Christopher came out publicly against the practice.[8] The new reform-oriented chief of police, police professionalization organizations, and the gay civil rights movement collectively pushed to end the Gayola practice.

New York

editGayola, as a form of bribery was also a common practice for New York City's gay bars in the mid-century.[9] While there was no large scale Gayola scandal in New York, the term Gayola mainly referred to the San Francisco scandal. Many gay bars and bathhouses did use bribery to avoid the attention of the police.[10] The Everard bathhouse's police association is what gave it the reputation of being safe from police investigation.[10] Similar to the Everard, Koenigs, a regular meet up place for gay men, as well as many other small businesses that served as meet ups, employed bribery. They paid them to the police for privacy and a lack of investigation into the clientele they served.[10] The employment of bribery became a facet of the business itself. Creating an internal system of bribe taking that extended beyond policemen and even ward politicians and social purity groups.[10] This system was enmeshed and protected by the social image of the 'fairy.' Due to this these plans were able to play out with little to no public backlash if they were discovered by the public.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Agee, Christopher (September 2006). "Gayola: Police Professionalization and the Politics of San Francisco's Gay Bars, 1950-1968". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 15 (3): 462–489. doi:10.1353/sex.2007.0024. JSTOR 4629672. PMID 19238767. S2CID 41863732.

- ^ Gibson, C.J. "Stoumen v. Reilly , 37 Cal.2d 713". Supreme Court of California Resources. Stanford Law School. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Asimov, Nanette (12 December 2003). "Bob Ross -- pioneering gay journalist and activist". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b Boyd, Nan Alamilla (2003-05-23). Wide-Open Town. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520938748. ISBN 978-0-520-93874-8.

- ^ a b c d e Series III: Major Project Records. Series III.B.6 Marine Cooks and Stewards Union Research Subject Files: General San Francisco Gay History: MCS-SFGH Events-1960-Gayola Scandal. 1960. MS The Allan Berube Papers: Series III: Major Project Records Box 89, Folder 4. Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society. Archives of Sexuality and Gender, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/GOCWJU916679870/AHSI?u=ohlnk162&sid=AHSI&xid=721aabea . Accessed 24 Nov. 2020. Berube, Allan. The Allan Berube Papers, "Outgrowth of Scandal," "Gratuities, Not Bribes." The San Francisco Chronicle, 1960

- ^ a b c d Politics—Gayola Scandal. June 8, 1960-July 12, 1962. MS Wide Open Town History Project Records Box 5, Folder 18. Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society. Archives of Sexuality and Gender, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MGEPHT474477939/AHSI?u=ohlnk162&sid=AHSI&xid=b61b7b20 . Accessed 24 November 2020.

- ^ Oral Histories by S. B.-G. C. n.d. MS Wide Open Town History Project Records Box 7, Folder 8. Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society. Archives of Sexuality and Gender, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MKEPNX382580298/AHSI?u=ohlnk162&sid=AHSI&xid=5e7b4e69 . Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

- ^ Carlsson, Carl. "Gay History and Politics in the Tenderloin". Shaping San Francisco's Digital Archive. Found SF. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ "Why Did the Mafia Own the Bar?". American Experience. PBS. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. Basic Books, 1994.