Game design is the process of creating and shaping the mechanics, systems, rules, and gameplay of a game. Game design processes apply to board games, card games, dice games, casino games, role-playing games, sports, war games, or simulation games.

In Elements of Game Design, game designer Robert Zubek defines game design by breaking it down into three elements:[3]

- Game mechanics and systems, which are the rules and objects in the game.

- Gameplay, which is the interaction between the player and the mechanics and systems. In Chris Crawford on Game Design, the author summarizes gameplay as "what the player does".[4]

- Player experience, which is how users feel when they are playing the game.

In academic research, game design falls within the field of game studies (not to be confused with game theory, which studies strategic decision making, primarily in non-game situations).

Process of design

editGame design is part of a game's development from concept to final form. Typically, the development process is iterative, with repeated phases of testing and revision. During revision, additional design or re-design may be needed.

Development team

edit

Game designer

editA game designer (or inventor) is a person who invents a game's concept, central mechanisms, rules, and themes. Game designers may work alone or in teams.

Game developer

editA game developer is a person who fleshes out the details of a game's design, oversees its testing, and revises the game in response to player feedback.

Often game designers also do development work on the same project. However, some publishers commission extensive development of games to suit their target audience after licensing a game from a designer. For larger games, such as collectible card games, designers and developers work in teams with separate roles.

Game artist

editA game artist creates visual art for games. Game artists are often vital to role-playing games and collectible card games.[5]

Many graphic elements of games are created by the designer when producing a prototype of the game, revised by the developer based on testing, and then further refined by the artist and combined with artwork as a game is prepared for publication or release.

Concept

editA game concept is an idea for a game, briefly describing its core play mechanisms, objectives, themes, and who the players represent.

A game concept may be pitched to a game publisher in a similar manner as film ideas are pitched to potential film producers. Alternatively, game publishers holding a game license to intellectual property in other media may solicit game concepts from several designers before picking one to design a game.

Design

editDuring design, a game concept is fleshed out. Mechanisms are specified in terms of components (boards, cards, tokens, etc.) and rules. The play sequence and possible player actions are defined, as well as how the game starts, ends, and win conditions (if any).

Prototypes and play testing

editA game prototype is a draft version of a game used for testing. Uses of prototyping include exploring new game design possibilities and technologies.[6]

Play testing is a major part of game development. During testing, players play the prototype and provide feedback on its gameplay, the usability of its components, the clarity of its goals and rules, ease of learning, and entertainment value. During testing, various balance issues may be identified, requiring changes to the game's design. The developer then revises the design, components, presentation, and rules before testing it again. Later testing may take place with focus groups to test consumer reactions before publication.

History

editFolk process

editMany games have ancient origins and were not designed in the modern sense, but gradually evolved over time through play. The rules of these games were not codified until early modern times and their features gradually developed and changed through the folk process. For example, sports (see history of sports), gambling, and board games are known, respectively, to have existed for at least nine thousand,[7] six thousand,[8] and four thousand years.[9] Tabletop games played today whose descent can be traced from ancient times include chess,[10][11] go,[12] pachisi,[13] mancala,[14][15] and pick-up sticks.[16] These games are not considered to have had a designer or been the result of a contemporary design process.

After the rise of commercial game publishing in the late 19th century, many games that had formerly evolved via folk processes became commercial properties, often with custom scoring pads or preprepared material. For example, the similar public domain games Generala, Yacht, and Yatzy led to the commercial game Yahtzee in the mid-1950s.[17][18]

Today, many commercial games, such as Taboo, Balderdash, Pictionary, or Time's Up!, are descended from traditional parlour games. Adapting traditional games to become commercial properties is an example of game design. Similarly, many sports, such as soccer and baseball, are the result of folk processes, while others were designed, such as basketball, invented in 1891 by James Naismith.[19][20]

New media

editThe first games in a new medium are frequently adaptations of older games. Later games often exploit the distinctive properties of a new medium. Adapting older games and creating original games for new media are both examples of game design.

Technological advances have provided new media for games throughout history. For example, accurate topographic maps produced as lithographs and provided free to Prussian officers helped popularize wargaming.[citation needed] Cheap bookbinding (printed labels wrapped around cardboard) led to mass-produced board games with custom boards.[citation needed] Inexpensive (hollow) lead figurine casting contributed to the development of miniature wargaming.[citation needed] Cheap custom dice led to poker dice.[citation needed] Flying discs led to Ultimate frisbee.[21][22]

Purposes

editGames can be designed for entertainment, education, exercise or experimental purposes. Additionally, elements and principles of game design can be applied to other interactions, in the form of gamification. Games have historically inspired seminal research in the fields of probability, artificial intelligence, economics, and optimization theory. Applying game design to itself is a current research topic in metadesign.

Educational purposes

editBy learning through play[a] children can develop social and cognitive skills, mature emotionally, and gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments.[23] Key ways that young children learn include playing, being with other people, being active, exploring and new experiences, talking to themselves, communicating with others, meeting physical and mental challenges, being shown how to do new things, practicing and repeating skills, and having fun.[24]

Play develops children's content knowledge and provides children the opportunity to develop social skills, competencies, and disposition to learn.[25] Play-based learning is based on a Vygotskian model of scaffolding where the teacher pays attention to specific elements of the play activity and provides encouragement and feedback on children's learning.[26] When children engage in real-life and imaginary activities, play can be challenging in children's thinking.[27] To extend the learning process, sensitive intervention can be provided with adult support when necessary during play-based learning.[26]

Design issues by game type

editDifferent types of games pose specific game design issues.

Board games

editBoard game design is the development of rules and presentational aspects of a board game. When a player takes part in a game, it is the player's self-subjection to the rules that create a sense of purpose for the duration of the game.[1] Maintaining the players' interest throughout the gameplay experience is the goal of board game design.[2] To achieve this, board game designers emphasize different aspects such as social interaction, strategy, and competition, and target players of differing needs by providing for short versus long-play, and luck versus skill.[2] Beyond this, board game design reflects the culture in which the board game is produced.

The most ancient board games known today are over 5000 years old. They are frequently abstract in character and their design is primarily focused on a core set of simple rules. Of those that are still played today, games like go (c. 400 BC), mancala (c. 700 AD), and chess (c. 600 AD) have gone through many presentational and/or rule variations. In the case of chess, for example, new variants are developed constantly, to focus on certain aspects of the game, or just for variation's sake.

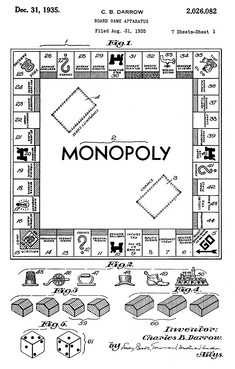

Traditional board games date from the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Whereas ancient board game design was primarily focused on rules alone, traditional board games were often influenced by Victorian mores. Academic (e.g. history and geography) and moral didacticism were important design features for traditional games, and Puritan associations between dice and the Devil meant that early American game designers eschewed their use in board games entirely.[28] Even traditional games that did use dice, like Monopoly (based on the 1906 The Landlord's Game), were rooted in educational efforts to explain political concepts to the masses. By the 1930s and 1940s, board game design began to emphasize amusement over education, and characters from comic strips, radio programmes, and (in the 1950s) television shows began to be featured in board game adaptations.[28]

Recent developments in modern board game design can be traced to the 1980s in Germany, and have led to the increased popularity of "German-style board games" (also known as "Eurogames" or "designer games"). The design emphasis of these board games is to give players meaningful choices.[1] This is manifested by eliminating elements like randomness and luck to be replaced by skill, strategy, and resource competition, by removing the potential for players to fall irreversibly behind in the early stages of a game, and by reducing the number of rules and possible player options to produce what Alan R. Moon has described as "elegant game design".[1] The concept of elegant game design has been identified by The Boston Globe's Leon Neyfakh as related to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's the concept of "flow" from his 1990 book, "Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience".[1]

Modern technological advances have had a democratizing effect on board game production, with services like Kickstarter providing designers with essential startup capital and tools like 3D printers facilitating the production of game pieces and board game prototypes.[29][30] A modern adaptation of figure games are miniature wargames like Warhammer 40,000.

Card games

editCard games can be designed as gambling games, such as Poker, or simply for fun, such as Go Fish. As cards are typically shuffled and revealed gradually during play, most card games involve randomness, either initially or during play, and hidden information, such as the cards in a player's hand.

How players play their cards, revealing information and interacting with previous plays as they do so, is central to card game design. In partnership card games, such as Bridge, rules limiting communication between players on the same team become an important part of the game design. This idea of limited communication has been extended to cooperative card games, such as Hanabi.

Dice games

editDice games differ from card games in that each throw of the dice is an independent event, whereas the odds of a given card being drawn are affected by all the previous cards drawn or revealed from a deck. For this reason, dice game design often centers around forming scoring combinations and managing re-rolls, either by limiting their number, as in Yahtzee or by introducing a press-your-luck element, as in Can't Stop.

Casino games

editCasino game design can entail the creation of an entirely new casino game, the creation of a variation on an existing casino game, or the creation of a new side bet on an existing casino game.[32]

Casino game mathematician, Michael Shackleford has noted that it is much more common for casino game designers today to make successful variations than entirely new casino games.[33] Gambling columnist John Grochowski points to the emergence of community-style slot machines in the mid-1990s, for example, as a successful variation on an existing casino game type.[34]

Unlike the majority of other games which are designed primarily in the interest of the player, one of the central aims of casino game design is to optimize the house advantage and maximize revenue from gamblers. Successful casino game design works to provide entertainment for the player and revenue for the gambling house.

To maximise player entertainment, casino games are designed with simple easy-to-learn rules that emphasize winning (i.e. whose rules enumerate many victory conditions and few loss conditions[33]), and that provide players with a variety of different gameplay postures (e.g. card hands).[32] Player entertainment value is also enhanced by providing gamblers with familiar gaming elements (e.g. dice and cards) in new casino games.[32][33]

To maximise success for the gambling house, casino games are designed to be easy for croupiers to operate and for pit managers to oversee.[32][33]

The two most fundamental rules of casino game design are that the games must be non-fraudable[32] (including being as nearly as possible immune from advantage gambling[33]) and that they must mathematically favor the house winning. Shackleford suggests that the optimum casino game design should give the house an edge of smaller than 5%.[33]

Tabletop role-playing games

editThe design of tabletop role-playing games typically requires the establishment of setting, characters, and gameplay rules or mechanics. After a role-playing game is produced, additional design elements are often devised by the players themselves. In many instances, for example, character creation is left to the players.

Early role-playing game theories developed on indie role-playing game design forums in the early 2000s.[35][36][37][38][39]

Game studies

editGame design is a topic of study in the academic field of game studies. Game studies is a discipline that deals with the critical study of games, game design, players, and their role in society and culture. Prior to the late-twentieth century, the academic study of games was rare and limited to fields such as history and anthropology. As the video game revolution took off in the early 1980s, so did academic interest in games, resulting in a field that draws on diverse methodologies and schools of thought.[40]

Social scientific approaches have concerned themselves with the question of, "What do games do to people?" Using tools and methods such as surveys, controlled laboratory experiments, and ethnography, researchers have investigated the impacts that playing games have on people and the role of games in everyday life.[41]

Humanities approaches have concerned themselves with the question of, "What meanings are made through games?" Using tools and methods such as interviews, ethnographies, and participant observation, researchers have investigated the various roles that games play in people's lives and the meanings players assign to their experiences.[42]

From within the game industry, central questions include, "How can we create better games?" and, "What makes a game good?" "Good" can be taken to mean different things, including providing an entertaining experience, being easy to learn and play, being innovative, educating the players, and/or generating novel experiences.[43][44][45]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a term used in education and psychology to describe how a child can learn to make sense of the world around them

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Neyfakh, Leon. "Quest for fun; Sometimes the most addictive new technology comes in a simple cardboard box". Boston Globe. 11 March 2012

- ^ a b c Wadley, Carma. "Rules of the game: Do you have what it takes to invent the next 'Monopoly'?" Deseret News. 18 November 2008.

- ^ Zubek, Robert (18 August 2020). Elements of Game Design. The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262043915. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Crawford, Chris (2003). Chris Crawford on Game Design. New Riders. ISBN 978-0-88134-117-1.

- ^ Exhibitions: The Art of Video Games – Accessed 17 November 2012.

- ^ Manker, Jon; Arvola, Mattias (January 2011). "Prototyping in Game Design: Externalization and Internalization of Game Ideas". Proceedings of Hci 2011 - 25th BCS Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ "Hartsell, Jeff., Wrestling 'in our blood,' says Bulldogs' Luvsandorj, 17 March 2011". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Bose, M. L. (1998). Social And Cultural History Of Ancient India (revised & Enlarged ed.). Concept Publishing Company. p. 179. ISBN 978-81-7022-598-0.

- ^ Soubeyrand, Catherine. "The Game of Senet". Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ Panaino, Antonio (1999). La novella degli scacchi e della tavola reale. Milano: Mimesis. ISBN 88-87231-26-5.

- ^ Andreas Bock-Raming, The Gaming Board in Indian Chess and Related Board Games: a terminological investigation, Board Games Studies 2, 1999

- ^ "Warring States Project Chronology #2". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ Lal, B.B. "The Painted Grey Ware culture of the Iron age" (PDF). Silk Road. I: 426–427. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Mancala". Savannah African Art Museum. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Natsoulas (1995). "The Game of Mancala with Reference to Commonalities among the Peoples of Ethiopia and in Comparison to Other African Peoples: Rules and Strategies". Northeast African Studies. 2 (2): 7–24. doi:10.1353/nas.1995.0018. JSTOR 41931202. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Arts of Asia. 1999. p. 122. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Wood, Clement and Goddard, Gloria, The Complete Book of Games, Halcyon House, NY, 1938

- ^ Coopee, Todd (7 August 2017). "Yahtzee from the E.S. Lowe Company". ToyTales.ca.

- ^ "YMCA International – World Alliance of YMCAs: Basketball : a YMCA Invention". www.ymca.int. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "The Greatest Canadian Invention". CBC News. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010.

- ^ Malafronte, Victor A. (1998). F. Davis Johnson (ed.). The Complete Book of Frisbee: The History of the Sport & the First Official Price Guide. Rachel Forbes (illus.). Alameda, Cal.: American Trends Publishing Company. ISBN 0-9663855-2-7. OCLC 39487710.

- ^ "History of Ultimate". Timeline of Events in Ultimate History. 22 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ Human growth and the development of personality, Jack Kahn, Susan Elinor Wright, Pergamon Press, ISBN 978-1-59486-068-3

- ^ Learning, playing, and interacting. Good practice in the early years foundation stage. Page 9[full citation needed]

- ^ Wood, E. and J. Attfield. (2005). Play, learning, and the early childhood curriculum. 2nd ed. London: Paul Chapman

- ^ a b Martlew, J., Stephen, C. & Ellis, J. (2011). Play in the primary school classroom? The experience of teachers supporting children's learning through a new pedagogy. Early Years, 31(1), 71–83.

- ^ Whitebread, D., Coltman, P., Jameson, H. & Lander, R. (2009). Play, cognition, and self-regulation: What exactly are children learning when they learn through play? Educational & Child Psychology, 26(2), 40–52.

- ^ a b Johnson, Bruce E. "Board games: affordable and abundant, boxed amusements from the 1930s and '40s recall the cultural climate of an era." Country Living. 1 December 1997.

- ^ Whigfield, Nick. "Video Hasn't Killed Interest in Board Games; New Technologies Have Contributed to Revival of Tabletop Entertainment". The Irish Times. 12 May 2014.

- ^ Hesse, Monica. "Rolling the dice on a jolly good pastime". The Washington Post. 29 August 2011.

- ^ Shackleford, Michael. "House Edge of casino games compared". Wizardofodds.com. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Lubin, Dan. "Casino Game Design: From Cocktail Napkin Sketch to Casino Floor". Available: [1]. Archived 4 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Shackleford, Michael. "Ten Commandments for Game Inventors". Wizardofodds.com. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ Grochowski, John. "Gaming Guru: Tracing Back the Roots of Some Popular Gaming Machines at Casinos". The Press of Atlantic City. 28 August 2013.

- ^ The Threefold Theory FAQ by John Kim

- ^ Everything You Need to Know about GEN Theory by Scarlet Jester

- ^ The Forge's article page, with the key articles to GNS Theory/Forge Theory

- ^ Color Theory by Fabien Ninoles

- ^ Channel Theory Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine, by Larry Hols

- ^ Konzack, Lars (2007). "Rhetorics of Computer and Video Game Research" in Williams & Smith (ed.) The Players' Realm: Studies on the Culture of Video Games and gaming. McFarland.

- ^ Crawford, G. (2012). Video Gamers. London: Routledge.

- ^ Consalvo, 2007[full citation needed]

- ^ Griffiths, M. (1999). "Violent video games and aggression: A review of the literature" (PDF). Aggression and Violent Behavior. 4 (2): 203–212. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(97)00055-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2013.

- ^ Rollings and Morris, 2000; Rouse III, 2001[full citation needed]

- ^ Fabricatore et al., 2002; Falstein, 2004[full citation needed]

Further reading

edit- Bates, Bob (2004). Game Design (2nd ed.). Thomson Course Technology. ISBN 978-1-59200-493-5.

- Baur, Wolfgang (2012). Complete Kobold Guide to Game Design. Open Design LLC. ISBN 978-1936781065.

- Burgun, Keith (2012). Game Design Theory: A New Philosophy for Understanding Games. A K Peters/CRC Press. ISBN 978-1466554207.

- Costikyan, Greg (2013). Uncertainty in Games. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262018968.

- Elias, George Skaff (2012). Characteristics of Games. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262017138.

- Hofer, Margaret (2003). The Games We Played: The Golden Age of Board & Table Games. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1568983974.

- Huizinga, Johan (1971). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0807046814.

- Kankaanranta, Marja Helena (2009). Design and Use of Serious Games. Intelligent Systems, Control and Automation: Science and Engineering. Springer. ISBN 978-9048181414..

- Moore, Michael E.; Novak, Jeannie (2010). Game Industry Career Guide. Delmar: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4283-7647-2.

- Norman, Donald A. (2002). The Design of Everyday Things. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465067107..

- Oxland, Kevin (2004). Gameplay and design. Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-20467-7.

- Peek, Steven (1993). The Game Inventor's Handbook. Betterway Books. ISBN 978-1558703155.

- Peterson, Jon (2012). Playing at the World. Unreason Press. ISBN 978-0615642048..

- Salen Tekinbad, Katie (2003). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262240451..

- Schell, Jesse (2008). The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0123694966.

- Somberg, Guy (6 September 2018). Game Audio Programming 2: Principles and Practices. CRC Press 2019. ISBN 9781138068919. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Tinsman, Brian (2008). The Game Inventor's Guidebook: How to Invent and Sell Board Games, Card Games, Role-Playing Games, & Everything in Between!. Morgan James Publishing. ISBN 978-1600374470.

- Woods, Stewart (2012). Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786467976.

- Zubek, Robert (August 2020). Elements of Game Design. The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262043915.