Galyon Hone (died 1552) was a glazier from Bruges who worked for Henry VIII of England at Hampton Court and in other houses making stained glass windows.[1] His work involved replacing the heraldry and ciphers of Henry VIII's wives in windows when the king remarried.[2]

Career

editHe is identified with "Gheleyn van Brugge" who joined the Guild of St Luke in Antwerp in 1492. Early work for Henry VIII includes glazing the windows of pavilions at the Field of the Cloth of Gold.[3]

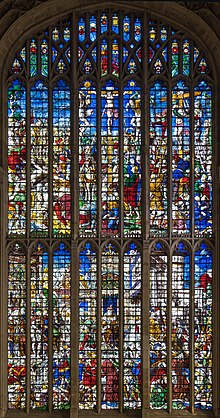

In England, Hone was made the King's glazier in succession to Barnard Flower. He worked at the Field of the Cloth of Gold.[4] Hone made glass for Eton College and King's College Chapel, Cambridge. Some of the payments for the windows at Eton were made to his wife. Three design drawings for the King's College windows are held by Bowdoin College, Maine, and can be related to contracts made by Galyon Hone and other glaziers in 1526. A design for stained glass in known as a "vidumus". The drawings at Bowdoin are in the manner of Dirck Vellert, an artist who worked in Antwerp.[5]

He lived in the parish of St Mary Magdalene and then in Southwark, where Henry VIII allowed him to employ six foreign journeymen instead of the two craftsmen usually permitted.[6] There was a community of artists and craftsmen from Holland and the Netherlands, and in 1547 Hone was mentioned in the will of his friend, the court goldsmith Cornelis Hayes.[7] Hone and the printer John Siberch were overseers of the will of a German painter living in Bermondsey, Henry Blankstone. Blankstone painted renaissance style borders and royal ciphers in the Long Gallery at Hampton Court.[8]

In 1533 Galyon Hone's work at Hampton Court included heraldic glass:

In the two great windows at the ends of the hall is two great arms with four beasts in them ... Also in the said windows in the hall is 30 of the King and Queens arms ... also badges of the King and Queen ... also 77 sceptres with the King's word ... glazing 11 side windows ...in the gable window at the east end the Queen's arms new set.[9]

Galyon Hone glazed an arbour or "herber" at the mount in the garden of Hampton Court in 1533.[10] He supplied heraldic glass before February 1534 for Henry VIII at Hunsdon House, Hertfordshire.[11] In 1534 he made some repairs at Woking Palace and at Westenhanger where he glazed the windows of a chamber for Princess Mary and her maidens.[12] At Greenwich Palace he added glass with badges of Jane Seymour in 1536,[13] and reworked old glass in the chapel at Leeds Castle.[14] He repaired windows at Leeds Castle for a visit by Catherine Parr in 1544.[15]

In 1541 Hone made windows for the presence chamber and watching chamber at Hampton Court, and provided glass for Henry's palace at The More.[16] In 1544, he glazed the windows of new lodgings around the base court of Dartford, a palace constructed in the former priory.[17]

Galyon Hone seems to have died in 1552.[18] He had a son, Gerrard Hone, who was also a glazier working in England. Gerrard Hone married Marion, a niece of the royal carpenter Thomas Stockton, and widow of Jasper Rolfe.[19]

During restoration work at Hampton Court in the 1840s by the glazier Thomas Willement, some stained glass, possibly by Galyon Hone, was recovered and removed. It was presented to the church of St Alban at Earsdon, near Whitley Bay by Lord Hastings of Delavel Hall in 1878.[20]

Withcote and Roger Ratcliffe

editSurviving windows at Withcote Chapel near Oakham may have been made by Galyon Hone. They were made for Roger Ratcliffe (died 1537), a former member of the household of Catherine of Aragon, and his wife Catherine, widow of William Smith alias Heriz, and daughter of William Ashby. The glass includes their heraldry and the phoenix badge of Jane Seymour. The attribution is based on the Flemish character of the painting, the use of royal insignia, and Ratcliffe's connection to the Henrician court.[21]

Roger Ratcliffe attended the queen at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, and was described as an usher of the privy chamber to Henry VIII in the Eltham Ordinance.[22] He went to Scotland in 1524 with Doctor Magnus to meet the king's sister Margaret Tudor. Ratcliffe's role was to amuse her son, the young James V of Scotland. They brought Henry's gift to Margaret, a length of cloth of gold, and a sword for James. They saw the king dance, sing, ride, run with a spear, and his other excellent "princely actes and doinggs". The mission was managed by Cardinal Wolsey.[23] Henry VIII allowed Ratcliffe to take building materials from Rockingham Castle to Withcote in 1534.[24]

Drawings for Cardinal Wolsey

editA surviving set of drawings seems to relate to Cardinal Wolsey's windows in the chapel at Hampton Court, and are held by the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. A design for stained glass is known as a "vidimus". The drawings may have been sent to Wolsey by an artist in Flanders, in the circle of Erhard Schön, and the glass made in London by the glazier James Nicholson. Hone altered the chapel windows by including the badges of Anne Boleyn and subsequently Jane Seymour. The windows were taken down by iconoclasts in 1645.[25]

References

edit- ^ Carola Hicks, The King's Glass: A Story of Tudor Power and Secret Art (London, 2007).

- ^ Hilary Wayment, 'Stained Glass in Henry VIII's palaces', David Starkey, Henry VIII: A European Court in England (London, 1991), p. 30.

- ^ Kenneth Harrison, The Windows of King's College Chapel (Cambridge, 1952), pp. 7–8: Mary Bryan Curd, Flemish and Dutch Artists in Early Modern England (Routledge, 2017).

- ^ Howard Colvin, History of the King's Works, 3:1 (London: HMSO, 1975), pp. 35, 411.

- ^ Richard Marks, 'Window Glass', John Blair & Nigel Ramsay, English Medieval Industries (London, 1991), p. 285-6: Hilary Wayment, 'The Great Windows of King's College', Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, 69 (1979), pp. 53-69.

- ^ Robert Tittler, Painting for a Living in Tudor and Early Stuart England (Boydell, 2022), 193.

- ^ Richard Marks, Stained Glass in England During the Middle Ages (Routledge, 1993), p. 207.

- ^ Matthew Groom, 'John Siberch, The First Cambridge Printer', Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 12:4 (2003), pp. 409-10.

- ^ Henry Cole alias Felix Summerly, A Hand-book for the Architecture, Tapistries, Paintings, Gardens and Grounds of Hampton Court (London, 1849), p. 67, modernised here.

- ^ Kenneth Harrison, The Windows of King's College Chapel (Cambridge, 1952), p. 9: Evelyn Cecil, Lady Rockley, History of Gardening in England (London, 1910), p. 72

- ^ Hilary Wayment, 'Stained Glass in Henry VIII's palaces', David Starkey, Henry VIII: A European Court in England (London, 1991), p. 30.

- ^ L. F. Salzman, Building in England (Oxford, 1952), p. 181: Letters and Papers Henry VIII, vol. 7 (London, 1883), p. 102 no. 250: TNA E101/504 f.63.

- ^ Howard Colvin, The History of the King's Works, 4:2 (London: HMSO, 1982), pp. 699, 703.

- ^ Hilary Wayment, 'Stained Glass in Henry VIII's palaces', David Starkey, Henry VIII: A European Court in England (London, 1991), p. 28.

- ^ Howard Colvin, History of the King's Works, 3:1 (London: HMSO, 1975), p. 262.

- ^ Howard Colvin, History of the King's Works, vol. 4 part 2 (HMSO, 1982), pp. 41, 164-169.

- ^ Howard Colvin, The History of the King's Works, 4:2 (London: HMSO, 1982), p. 73.

- ^ Howard Colvin, History of the King's Works, 3:1 (London: HMSO, 1975), p. 35.

- ^ Kenneth Harrison, The Windows of King's College Chapel Cambridge (Cambridge, 1952), p. 11.

- ^ Nikolaus Pevsner, Northumberland (London, 1992), p. 261.

- ^ Christopher Woodforde, 'The Painted Glass in Withcote Church', Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 75:436 (July 1939), pp. 17-22.

- ^ A Collection of Ordinances and Regulations for the Government of the Royal Household (London, 1790), p. 154.

- ^ Mary Anne Everett Green, Letters of royal and illustrious ladies of Great Britain, vol. 1 (London, 1846), pp. 352-4 citing BL Cotton Caligula B VI: State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 part 4 (London, 1836), pp. 90, 139, 208-9, 243.

- ^ Howard Colvin, History of the King's Works, vol. 2 (London, 1976), p. 818: Charles Wise, 'Henry VIII at Rockingham Park', The Antiquary, 28 (London, 1893), p. 194.

- ^ Hilary Wayment, Twenty-Four Vidimuses for Cardinal Wolsey, Master Drawings, vol. 23/24 no. 4 (1986), pp. 503-517, a related drawing is held by the National Galleries of Scotland.