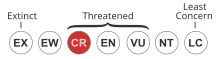

The Polynesian ground dove or Society Islands ground dove (Pampusana erythroptera) or Tutururu is a critically endangered species of bird in the family Columbidae. Originally endemic to the Society Islands and Tuamotus in French Polynesia, it has now been extirpated from most of its former range by habitat loss and predation by introduced species such as cats and rats, and the species is now endemic only in the Acteon islands. The total population is estimated to be around 100-120 birds.

| Polynesian ground dove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of both the albicollis (left) and erythroptera (right) color morphs by John Gerrard Keulemans, 1893 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Genus: | Pampusana |

| Species: | P. erythroptera

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pampusana erythroptera (Gmelin, JF, 1789)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

It favors tropical forests, especially with Pandanus tectorius, Pisonia grandis and shrubs, but it has also been recorded from dense shrub growing below coconut palms.

A rat eradication campaign from 2015 to 2017 has allowed the ground dove to reestablish itself on Tenarunga.

Taxonomy

editThe Polynesian ground dove was formally described in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it with all the other pigeons and doves in the genus Columba and coined the binomial name Columba erythroptera.[3] Gmelin based his description on the "Garnet-winged pigeon" that had been described in 1783 by the English ornithologist John Latham from a preserved specimen provided by Joseph Banks, that had been collected on the island of Moorea near Tahiti in French Polynesia.[4] The etymology of the genus name Pampusana is uncertain. The specific epithet erythroptera combines the Ancient Greek eruthros meaning "red" with -pteros meaning "-winged".[5] The Polynesian ground dove forms a superspecies with its closest living relatives, the white-breasted, white-fronted, and white-throated ground doves.[6] This superspecies is closely related to the Tongan, Santa Cruz, and thick-billed ground doves.[6]

This species was formerly placed in the genus Alopecoenas Sharpe, 1899, but the name of the genus was changed in 2019 to Pampusana Bonaparte, 1855 as this name was found to have priority.[7][8]

Numerous forms of the Polynesian ground dove have been depicted from the various islands and atolls that used to make up its range; however, most of the original specimens have been lost and are now represented only by paintings, and some of the proposed forms may be from inaccurate descriptions and paintings.[9] Only one subspecies is generally recognized: the nominate subspecies, Pampusana erythroptera erythroptera, which was described by Gmelin in 1789 and was originally found on Tahiti, Moorea, Maria Est, Marutea Sud, Matureivavao, Rangiroa, Tenararo, Tenarunga, Vanavana, Hao, Hiti, and Tahanea.[10] P. e. albicollis, which was described by Tommaso Salvadori in 1892, was used for the birds found on Hao, Hiti, and probably Tahanea, but is now thought to be a color morph and was synonymized with P. e. erythroptera in 2022 by the International Ornithological Congress.[10][11][12] A third subspecies was initially described as G. e. pectoralis in 1848 by Titian Peale from a female specimen collected on Arakita; however, as no male specimen was described from the island, it is impossible to ascribe this bird to a specific subspecies and G. e. pectoralis was declared invalid.[10] The Polynesian ground dove is only known from female specimens for the remainder of its range, and therefore the populations from these islands are not ascribable to a subspecies.[10]

The Polynesian ground dove is also known locally as the Tutururu, as well as the Tuamotu ground dove, the white-collared ground dove, the white-breasted ground dove, the Society ground dove, the Society Islands ground dove, and the Tuamotu Islands ground dove.[9]

Description

editThe Polynesian ground dove is a small, plump ground dove that displays sexual dimorphism.[9] The male Polynesian ground doves of the nominate subspecies have white foreheads, cheeks, throats, and breasts.[13] The crown, nape, and auricular stripe are grey.[13] The upperparts are a dark olive grey with purple or, if the feathers have faded, chestnut red iridescence on the hindneck and wing-coverts.[13] The underparts are blackish. In males of the subspecies albicollis, the head is completely white.[13] Females of both subspecies look the same: they are a bright reddish brown overall, tinged strongly with reddish-purple on the crown, neck, and wing-coverts.[13] The mantle, back, rump, and inner wing-coverts are a dark olive, and there is a pale breast shield.[13] This plumage frequently fades in intensity due to wear.[13] The juvenile Polynesian ground dove is red overall, with many of its feathers fringed with a cinnamon-rufous.[13] The white parts of the face and underparts are suffused with grey.[9] Juvenile males can be differentiated from juvenile females through the absence of a pale breast shield and purple-edged feathers on the scapulars and lesser coverts.[13] The adult Polynesian ground dove is about 23.5 to 26 cm (9.3 to 10.2 in) in length, and weighs about 105 to 122 g (3.7 to 4.3 oz).[9] The ground dove's iris is brown, while the bill is black.[13] The legs and feet are a purplish black.[13]

The call of the Polynesian ground dove has been described as a low, hoarse moan.[9]

Distribution and habitat

editThe Polynesian ground dove was originally found in both the Tuamotu Archipelago and the Society Islands.[9] It has since been extirpated from the Society Islands, where it was found on Tahiti and Moorea.[9] In the Tuamotus it has been recorded on Arakita, Hao, Hiti, Maria Est, Marutea Sud, Matureivavao, Rangiroa, Tenararo, Tenarunga, and Vanavana.[9] In addition, local reports have suggested that the Polynesian Ground Dove likely lived on Fakarava, Fangatau, Katiu, Makemo, Manihi, Reao, Tahanea, Tematagi, Tikehau, Tuanake, Vahanga and Vahitahi, although no specimens were ever collected from these islands.[9]

Originally, the Polynesian ground dove inhabited mountainous volcanic islands and nearby atolls and islets.[9] However, the introduction of feral cats and rats have extirpated the ground dove from the mountainous volcanic islands. On the islets and atolls it lives in forests with a well-developed understory of dense bushes, ferns, and grasses, in areas of low, dense scrub, and in groves of Pandanus plants with sparse ground vegetation.[9]

Behaviour and ecology

editThe Polynesian ground dove is a terrestrial and elusive dove.[9] It primarily feeds by scratching for seeds on the ground, such as those from Morinda and Tournefortia plants; however, it is also known to feed in trees and shrubs, where it eats the buds of Portulaca, the seeds of Digitaria, and the leaves of Euphorbia.[9][13] The ground dove flushes in a manner similar to a partridge, while its wings produce a whirring sound.[9] Little is known about the species' breeding behavior, although juveniles have been observed in January and April.[13]

Status

editThe Polynesian ground dove once was abundant on most of the islands it lived on.[9] However, as this terrestrial species has no native mammalian predators, it is very vulnerable to the introduced feral cats and rats.[9] The ground dove became locally extinct on most islands shortly after they were discovered by Europeans, and it is thought that the populations were already at low levels well before that.[9] Since 1950, the ground dove has only been recorded on two islands: three specimens were collected from Matureivavao, while Rangiroa Atoll was discovered to host a small population of 12 to 20 birds on two of its islands in 1991.[9] It is believed to be extinct in the Society Islands and extirpated from much of its range in the Tuamotus; however, these islands are rarely visited by ornithologists, and many small islets need to be explored to determine if they also host a surviving population of the Polynesian ground dove.[9][13] Additionally, a survey in the 1970s missed the population of ground doves on Rangiroa Atoll, implying that it may survive undetected on other islets.[13] In addition to the threat from introduced predators, the low-lying atolls on which it survives are threatened by rising sea levels.[9]

Conservation efforts

editEfforts have been made to allow the species to reexpand by removal of invasive predators and restoration of native ecosystems. On the Acteon islands, likely home to the last viable population, habitat restoration efforts throughout 2017 by Island Conservation allowed the ground dove and the endangered Tuamotu sandpiper to reestablish themselves on Tenarunga, which was not possible for decades.[14][15] In 2020, monitoring found the population was slowly recovering.[16]

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Alopecoenas erythropterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1937). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 3. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 137.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 775.

- ^ Latham, John (1783). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 2, Part 2. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. p. 624, No. 13.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 290, 150. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b Baptista 1997, p. 181

- ^ Bruce, M.; Bahr, N.; David, N. (2016). "Pampusanna vs. Pampusana: a nomenclatural conundrum resolved, along with associated errors and oversights" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 136: 86–100.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Pigeons". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Gibbs 2001, p. 407

- ^ a b c d Gibbs 2001, p. 408

- ^ Thibault, Jean-Claude (2017). Birds of eastern Polynesia : a biogeographic atlas. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-16728-05-3. OCLC 1041381313.

- ^ "IOC World Bird List 12.1". doi:10.14344/ioc.ml.12.1. S2CID 246050277.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Baptista 1997, p. 182

- ^ BirdLife International. "Paradise saved: some of world's rarest birds rebound on Pacific islands cleared of invasive predators". www.birdlife.org. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- ^ "How the Tutururu Became the Bellwether for Threatened Species in Acteon and Gambier". Island Conservation. April 16, 2019. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ "Libéré du rat, le Tutururu reprend des couleurs" (in French). Tahiti Infos. 6 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

Cited texts

edit- Baptista, L.F.; Trail, P.W.; Horblit, H.M. (1997). "Columbiformes. Family Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 4: Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 60–243. ISBN 978-84-87334-22-1.

- Gibbs, David; Barnes, Eustace; Cox, John (2001). Pigeons and Doves: A Guide to the Pigeons and Doves of the World. Sussex: Pica Press. ISBN 1-873403-60-7.