The Gaborone Dam is a dam on the Notwane River in Botswana with a capacity of 141,100,000 cubic metres (4.98×109 cu ft).[2] The dam is operated by the Water Utilities Corporation, and supplies water to the capital city of Gaborone.[3]

| Gaborone Dam | |

|---|---|

Gaborone Dam at sunset | |

| Country | Botswana |

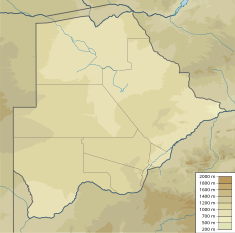

| Location | South-East District |

| Coordinates | 24°42′01″S 25°55′35″E / 24.700161°S 25.926381°E |

| Purpose | Urban water supply |

| Construction began | 1963 |

| Opening date | 1964 |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Embankment, earth-fill |

| Height | 25 metres (82 ft) |

| Length | 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) |

| Reservoir | |

| Total capacity | 141,100,000 cubic metres (4.98×109 cu ft) |

| Surface area | 15 square kilometres (5.8 sq mi).[1] |

Location

editThe Gaborone Dam is located south of Gaborone along the Gaborone-Lobatse road, and provides water for both Gaborone and Lobatse.[4] The effective catchment area covers about 225 square kilometres (87 sq mi), drained by the Notwane river and the lesser Taung, Metsemaswaane and Nywane rivers.[5] Between 1971 and 2000, average annual rainfall was between 450 millimetres (18 in) and 550 millimetres (22 in). Temperatures range from 10 °C (50 °F) in winter to 37 °C (99 °F) in summer. Average potential evapotranspiration is about 1,400 millimetres (55 in) annually.[6][a]

Description

editThe dam construction began in 1963, capturing water from the Notwane River, at a time when the new capital city of Gaborone was in the planning stages.[7] The original dam was completed in 1964.[8] The dam is an earthcore fill structure.[1] During the 1965-66 rainy season the reservoir filled and overflowed.[7]

Between 1983 and 1985 the dam was raised by 7 metres (23 ft) to increase capacity, reaching a maximum height of 25 metres (82 ft) and a length of 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi). Raising the dam had to be done extremely carefully to ensure that the impervious upstream zone of the dam remained intact and was extended up the raised bank.[8] Most of the reservoir is less than 10 feet (3.0 m) deep.[9] The surface area of the reservoir when full is 15 square kilometres (5.8 sq mi).[1]

Until completion of the Dikgatlhong Dam in 2011, the Gaborone dam was the largest in Botswana.[4]

Issues

editAfter the dam was opened and filled, the average water levels began to drop. In the part, this was due to a cyclical change in rainfall, reducing the amount of water fed into the reservoir and increasing the impact of evaporation in the hot, dry climate. In part it was due to growth of the city and growing per-capita demand for water as the population became more affluent, using water for purposes such as filling swimming pools and washing cars. By the end of 2002 the reservoir was 79% full, and by the start of 2004 it was 54% full.[10] By the end of 2004 the reservoir was just 27% full and the government was forced to impose harsh restrictions on water use.[11] By September 2005 the reservoir was down to 17% full, or 34 litres (7.5 imp gal; 9.0 US gal) per citizen of Gaborone.[11]

In the drought-prone country, the water supply is a constant concern. A neon signboard in the city informs residents how full the reservoir is.[7] The reservoir and the green buffer zone that surrounds it are the largest and most fragile ecosystem in the Gaborone area.[12] A book published in 2004 noted that storm water drainage is poor in Gaborone, causing recurring street floods, and that pit latrines and overflowing sewage ponds endanger the water in the reservoir.[13]

Reservoir use

editThe reservoir is starting to be marketed as a recreational area. The northern end of the reservoir is planned to become an entertainment venue called The Waterfront.[14] There is a yacht club, called Gaborone Yacht Club, on the northern side of the lake.[15] The southern end houses the Kalahari Fishing Club and a new public facility called City Scapes. City Scapes contains parks, playgrounds, and boating facilities.[14] The dam is popular with birdwatchers, windsurfers, and anglers.[16] However, there is no swimming due to crocodiles and parasitic bilharzias, which can transmit the serious disease schistosomiasis.[17]

Gallery

edit-

View from space

-

Gaborone from the air, dam in the distance

References

editNotes

- ^ In a dry environment where annual precipitation is lower than potential evapotranspiration, the soil and even the river beds will often be dry except in the rainy season.

Citations

- ^ a b c Water Utilities Corporation 2010.

- ^ Central Statistics Office 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Corporate Profile - WUC.

- ^ a b Central Statistics Office 2009.

- ^ Yadava 2003, p. 125.

- ^ Yadava 2003, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Gaborone in Details...

- ^ a b Knight 1990, p. 407-408.

- ^ Workman 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Workman 2009, p. 130.

- ^ a b Workman 2009, p. 139.

- ^ Keiner et al. 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Keiner et al. 2004, p. 92.

- ^ a b All about Gaborone.

- ^ Gaborone Yacht Club.

- ^ HardyFirestone 2007, p. 75–88.

- ^ African cities- Gaborone Culture.

Sources

- "African cities- Gaborone Culture". Gaborone.info. AfricanCities.net. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- "All about Gaborone". Gaborone, Botswana: Gabscity.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- "Botswana water statistics" (PDF). Gaborone, Botswana: Central Statistics Office. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- "Gaborone in Details..." Botswana Tourism. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- "HOME / ABOUT US". Gaborone Yacht Club. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- "Corporate Profile". WUC. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Hardy, Paula; Firestone, Matthew D. (2007). "Gaborone". Botswana & Namibia. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-760-8. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- Keiner, Marco; Zegras, Christopher; Schmid, Willy A.; Salmerón, Diego (20 December 2004). From Understanding to Action: Sustainable Urban Development in Medium-Sized Cities in Africa and Latin America. Springer. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4020-2879-3. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Knight (1 June 1990). Geotechnical Instrumentation in Practice: Purpose, Performance and Interpretation : Proceedings of the Conference Geotechnical Instrumentation in Civil Engineering Projects. Thomas Telford. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-7277-1515-9. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Water Utilities Corporation (2010). "Dam Parameters". Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Workman, James G. (4 August 2009). Heart of Dryness: How the Last Bushmen Can Help Us Endure the Coming Age of Permanent Drought. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-8027-1558-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Yadava, Ram Narayan (2003). Watershed Hydrology. Allied Publishers. p. 125. ISBN 978-81-7764-547-7. Retrieved 18 September 2012.