A funeral director, also known as an undertaker or mortician (American English), is a professional who has licenses in funeral arranging and embalming (or preparation of the deceased) involved in the business of funeral rites. These tasks often entail the embalming and burial or cremation of the dead, as well as the arrangements for the funeral ceremony (although not the directing and conducting of the funeral itself unless clergy are not present). Funeral directors may at times be asked to perform tasks such as dressing (in garments usually suitable for daily wear), casketing (placing the corpse in the coffin), and cossetting (applying any sort of cosmetic or substance to the best viewable areas of the corpse for the purpose of enhancing its appearance) with the proper licenses. A funeral director may work at a funeral home or be an independent employee.

Etymology

editThe term mortician is derived from the Latin word mort- ('death') with the ending -ician. In 1895, the trade magazine The Embalmers' Monthly put out a call for a new name for the profession in the US to distance itself from the title undertaker, a term that was then perceived to have been tarnished by its association with death. The term mortician was the winning entry.[1][2]

History

editPeople's need to respect the dead and their survivors is as ancient as civilization itself, and death care is among the world's oldest professions. Ancient Egypt is a probable pioneer in supporting full-time morticians; intentional mummification began around 2600 BC, with the best-preserved mummies dating to around 1570 to 1075 BC. Specialized priests spent 70 full days on a single corpse. Only royalty, nobility and wealthy commoners could afford the service, considered by some to be essential for accessing eternal life; the poorer performed very basic intentional mummification or simply buried the body in a dry spot hoping it would naturally mummify. In every case, an intact body was considered paramount to access the afterlife.[3]

Across successive cultures, religion remained a prime motive for securing a body against decay and/or arranging burial in a planned manner; some considered the fate of departed souls to be fixed and unchangeable (e.g. ancient Mesopotamia) and considered care for a grave to be more important than the actual burial.[4]

In ancient Rome, wealthy individuals trusted family to care for their corpse, but funeral rites would feature professional mourners: most often actresses who would announce the presence of the funeral procession by wailing loudly. Other paid actors would don the masks of ancestors and recreate their personalities, dramatizing the exploits of their departed scion. These purely ceremonial undertakers of the day nonetheless had great religious and societal impact; a larger number of actors indicated greater power and wealth for the deceased and their family.[5]

Modern ideas about proper preservation of the dead for the benefit of the living arose in the European Age of Enlightenment. Dutch scientist Frederik Ruysch's work attracted the attention of royalty and legitimized postmortem anatomy[clarification needed].[6] Most importantly, Ruysch developed injected substances and waxes that could penetrate the smallest vessels of the body and seal them against decay.[5]

Historically, from ancient Egypt to Greece and Rome to the early United States, women typically did all of the preparation of dead bodies.[7] They were called "layers out of the dead". In the mid-19th century, gender roles within funeral service in the United States began to change. In the late 19th century, the industry became male dominated with the development of funeral directors, which changed the funeral industry both locally and nationally.[8]

Role in the United States

editIn 2003, 15 percent of corporately owned funeral homes in the US were owned by one of three corporations.[9] The majority of morticians work in small, independent family-run funeral homes. The owner usually hires two or three other morticians to help them. Often, this hired help is in the family, perpetuating the family's ownership. Other firms that were family-owned have been acquired and are operated by large corporations such as Service Corporation International, though such homes usually trade under their pre-acquisition names.[9]

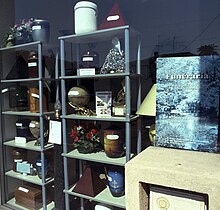

Most funeral homes have one or more viewing rooms, a preparation room for embalming, a chapel, and a casket selection room. They usually have a hearse for transportation of bodies, a flower car, and limousines. They also normally sell caskets and urns.[10]

Organizations and licensing in the United States

editLicensing requirements in the US are determined at the state level.[11] Most require a combination of post-secondary education (typically an associate's degree), passage of a National Board Examination,[12] passage of a state board examination, and one to two years' work as an apprentice.[13]

Role in the UK

editA funeral director in the UK will usually take on most of the administrative duties and arrangement of the funeral service, including flower arrangements, meeting with family members, and overseeing the funeral and burial service. Embalming or cremation of the body requires further training.[14]

Organizations and licensing in the UK

editIn the UK no formal licence is required to become an undertaker (funeral director). There are national trade organizations such as the British Institute of Funeral Directors (BIFD), the National Association of Funeral Directors (NAFD) and the Society of Allied and Independent Funeral Directors (SAIF).

The BIFD offers a licence to funeral directors who have obtained a diploma-level qualification; these diplomas are offered by both the BIFD and NAFD.

The British Institute of Embalmers (BIE) offers embalming training and qualifications.[citation needed]

All of the national organizations offer voluntary membership of "best practice" standards schemes, which includes regular premises inspection and adherence to a specific code of conduct.

These organizations help funeral directors demonstrate that they are committed to continuing professional development, and they have no issue with regulation should it become a legal requirement.[15][16][17]

Role in Canada

editThe role of a funeral director in Canada can include embalming, sales, oversight of funeral services as well as other aspects of needed funeral services.[18]

Organizations and licensing in Canada

editA funeral director in Canada will assume many responsibilities after proper education and licensing. Courses will include science and biology, ethics, and practical techniques of embalming.[18] There are a number of organizations available to Canadian funeral directors.[19][20]

References

edit- ^ "How Morticians Reinvented Their Job Title". Mental Floss. 5 January 2016.

- ^ "mortician, n. meanings, etymology and more | Oxford English Dictionary".

- ^ "Encyclopedia Smithsonian: Egyptian Mummies".

- ^ "Death in Ancient Civilisations". History. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015.

- ^ a b Steven Fife. "The Roman Funeral". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Frederik Ruysch: The Artist of Death". The Public Domain Review.

- ^ Quigley, Christine (1996). The Corpse: A History. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786401703.

- ^ "Funerals and Burial Practices | Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia". philadelphiaencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ a b Turner, Chelsea. "Corporate Growth in Funeral Home Industry". www.cga.ct.gov. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ "Funeral Directors." Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2006-07 Edition. 4 Aug, 2006. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 8 Dec, 2008. http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos011.htm

- ^ "Licensing Boards & Requirements".

- ^ theconferenceonline.org, Students' NBE

- ^ American Board of Funeral Service Education, Frequently Asked Questions Archived 3 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The British Institute of Funeral Directors". www.bifd.org.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "National Association of Funeral Directors".

- ^ "The British Institute of Funeral Directors".

- ^ "UK Independent Funeral Directors".

- ^ a b "Funeral Services | ontariocolleges.ca". www.ontariocolleges.ca. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "Home". OFSA.

- ^ "Funeral Service Association of Canada - Home". www.fsac.ca.