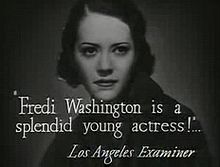

Fredericka Carolyn[citation needed] "Fredi" Washington (December 23, 1903 – June 28, 1994) was an American stage and film actress, civil rights activist, performer, and writer. Washington was of African American descent. She was one of the first Black Americans to gain recognition for film and stage work in the 1920s and 1930s.

Fredi Washington | |

|---|---|

Washington in Imitation of Life, 1934 | |

| Born | Fredericka Carolyn Washington December 23, 1903 Savannah, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | June 28, 1994 (aged 90) Stamford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Education | Julia Richman High School |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1922–1950 |

| Known for | |

| Spouses | |

Washington was active in the Harlem Renaissance (1920s–1930s). Her best- known film role was as Peola in Imitation of Life (1934). She plays a young light-skinned Black woman who decides to pass as white. Her last film role was in One Mile from Heaven (1937). After that she left Hollywood and returned to New York to work in theatre and civil rights activism.

Early life

editFredi Washington was born in 1903 in Savannah, Georgia, to Robert T. Washington, a postal worker, and Harriet "Hattie" Walker Ward, a dancer. Both were of African American and European ancestry.[1] Washington was the second of their five children. Her mother died when Fredi was 11 years old.[2] As the oldest girl in her family, she helped raise her younger siblings, Isabel, Rosebud, and Robert, with the help of their grandmother.[citation needed]

After their mother's death, Washington and her sister Isabel were sent to the St. Elizabeth's Convent School for Colored Girls in Cornwells Heights, near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[3]

While Washington was still in school in Philadelphia, her family moved north from Georgia to Harlem, New York. Washington graduated from Julia Richman High School in New York City.[4]

Career

editEarly entertainment career

editWashington's entertainment career began in 1921 as a chorus girl in the Broadway musical Shuffle Along. She was hired by dancer Josephine Baker as a member of the "Happy Honeysuckles," a cabaret group.[1] Baker became a friend and mentor to her.[5] Washington's collaboration with Baker led to her being discovered by producer Lee Shubert. In 1926, she was recommended for a co-starring role on the Broadway stage with Paul Robeson in the play Black Boy.[3] She quickly became a popular, featured dancer, and toured internationally with her dancing partner, Al Moiret.[4]

Washington turned to acting in the late 1920s. Her first movie role was in Black and Tan (1929), in which she played a Cotton Club dancer who was dying. She acted in a small role in The Emperor Jones (1933) starring Robeson. Washington played Cab Calloway's love interest in the musical short Cab Calloway's Hi-De-Ho (1934).[6]

Imitation of Life

editHer best-known role was in the 1934 movie Imitation of Life. Washington played a young light-skinned Black[1] woman who chose to pass as white to seek more opportunities in a society restricted by legal and social racial segregation. As Washington had visible European ancestry, the role was considered perfect for her, but it led to her being typecast by filmmakers.[3] Moviegoers sometimes assumed from Washington's appearance—her blue-gray eyes, pale complexion, and light brown hair—that she might have passed in her own life. In 1934, she said the role did not reflect her off-screen life, but "If I made Peola seem real enough to merit such statements, I consider such statements compliments and makes me feel I've done my job fairly well."[7][1]

She told reporters in 1949 that she identified as Black "...because I'm honest, firstly, and secondly, you don't have to be white to be good. I've spent most of my life trying to prove to those who think otherwise ... I am a Negro and I am proud of it."[7] Imitation of Life was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, but it did not win. Years later, in 2007, Time magazine ranked it as among "The 25 Most Important Films on Race."[8]

Activism

editWashington's experiences in the film industry and theater led her to become a civil rights activist. In an effort to help other Black actors and actresses find more opportunities, in 1937 Washington co-founded the Negro Actors Guild of America (NAG), with Noble Sissle, W. C. Handy, Paul Robeson, and Ethel Waters.[6] The organization's mission included speaking out against stereotyping and advocating for a wider range of roles.[2] Washington served as the organization's first executive secretary.[9][6]

She was also deeply involved with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, known as the NAACP.[10] While working with the NAACP, Washington fought for more representation and better treatment of Black actors in Hollywood; because of her own success, she was one of the few Black actors in Hollywood who had some influence with white studio executives.

In addition to working for the rights and opportunities of Black actors, Washington also advocated for the federal protection of Black Americans. She was a lobbyist for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, which the NAACP supported.[11] It was passed by the House but lost in the Senate, which was dominated by the Solid South.[citation needed]

Later work

editWashington played opposite Bill Robinson in Fox's One Mile from Heaven (1937), in which she played a light-skinned Black woman claiming to be the mother of a "white" baby. Claire Trevor plays a reporter who discovers the story and helps both Washington and the white biological mother (Sally Bane) who had given up the baby.[12][13] According to the Museum of Modern Art in 2013: "The last of the six Claire Trevor 'snappy' vehicles [Allan] Dwan made for Fox in the 1930s tests the limits of free expression on race in Hollywood while sometimes straining credulity."[14]

Washington appeared in the 1939 Broadway production of Mamba's Daughters, along with Ethel Waters and Georgette Harvey. She later became a casting consultant for the stage productions of Carmen Jones (1943) and George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess.[6][15]

Leaving Hollywood for radio

editDespite receiving critical acclaim, she was unable to find much work in the Hollywood of the 1930s and 1940s. Studios preferred Black actresses with darker skin, who were usually typecast as maids, cooks or other servants.[16] Directors were also reluctant to cast a light-skinned Black actress in a romantic role with a white leading man; the film production code prohibited suggestions of miscegenation. Interracial marriage was illegal in the South and many other states. Hollywood directors did not offer her any romantic roles.[17] As one modern critic explained, Fredi Washington was "...too beautiful and not dark enough to play maids, but rather too light to act in all-Black movies..."[18]

Washington had a dramatic role in a 1943 radio tribute to Black women, Heroines in Bronze, produced by the National Urban League,[19] but there were few regular dramatic radio programs in that era with Black protagonists. She wrote an opinion piece for the Black press in which she discussed how limited the opportunities in broadcasting were for Black actors, actresses, and vocalists, saying that "...radio seems to keep its doors sealed [against] colored artists."[20]

In 1945 she said:

"You see I'm a mighty proud gal, and I can't for the life of me find any valid reason why anyone should lie about their origin, or anything else for that matter. Frankly, I do not ascribe to the stupid theory of white supremacy and to try to hide the fact that I am a Negro for economic or any other reasons. If I do, I would be agreeing to be a Negro makes me inferior and that I have swallowed whole hog all of the propaganda dished out by our fascist-minded white citizens."[21]

Writer

editWashington was a theater writer, and the entertainment editor for The People's Voice (1942–1948), a newspaper for African Americans founded by Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a Baptist minister and politician in New York City. He was married to her sister Isabel Washington Powell.[1][22]

Personal life

editIn 1933, Washington married Lawrence Brown, the trombonist in Duke Ellington's jazz orchestra.[23] That marriage ended in divorce.[1] In 1952, Washington married a Stamford dentist, Hugh Anthony Bell, and moved to Greenwich, Connecticut.[24]

Death

editFredi Washington Bell died, aged 90, on June 28, 1994.[26] She died from pneumonia following a series of strokes at St. Joseph Medical Center in Stamford, Connecticut.[27][1]

Legacy and honors

edit- In 1975, Washington was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame.[4]

- In 1979, Washington received the CIRCA Award for lifetime achievement in the performing arts.[6]

- In 1981, Washington received an award from the Audience Development Company (AUDELCO), a New York-based nonprofit group devoted to preserving and promoting African-American theater.[15]

Filmography

edit- Square Joe (1922), her film debut[28]

- Black and Tan (1929)

- The Emperor Jones (1933)

- Imitation of Life (1934)

- Ouanga (1936)

- One Mile from Heaven (1937)

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Rule, Sheila (June 30, 1994). "Fredi Washington, 90, Actress; Broke Ground for Black Artists". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ^ a b Nzinga Cotton. "Fredi Washington: Active Promoter of Rights for Black Entertainers", New Nation (London, UK), June 16, 2008, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Frank William . "Acclaimed Actress Fredi Washington, 90, Has Passed Away", Philadelphia Tribune, August 12, 1994, p. 4D.

- ^ a b c Bourne, Stephen. "Obituary: Fredi Washington", The Independent (London, UK), July 4, 1994.

- ^ Veronica Chambers. "Lives Well Lived: Fredi Washington, The Tragic Mulatto", The New York Times, January 1, 1995, p. A27.

- ^ a b c d e Bracks, Lean'tin L.; Smith, Jessie Carney (2014). Black Women of the Harlem Renaissance Era. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8108-8543-1.

- ^ a b Hobbs, Allyson (2014). A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life. Harvard University Press. pp. 170–2.

- ^ "The 25 Most Important Films on Race: 'Imitation of Life'", Time, February 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ "Fredi Washington, Edna Thomas Honored by Guild", Norfolk (VA), New Journal and Guide, July 5, 1941, p. 15.

- ^ "Remembering Fredi Washington: Actress, Activist, and Journalist". connecticuthistory.org. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Favara, Jeremiah; Stabile, carol; Strait, Laura. "WASHINGTON, FREDI: DANCER, ACTRESS, JOURNALIST". broadcast41.uoregon.edu. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Overview: "One Mile from Heaven (1937)", The New York Times. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ Poster for One Mile from Heaven Archived March 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, A Cinema Apart website

- ^ One Mile from Heaven, screening June 13, 2013, part of exhibit: Allan Dwan and the Rise and Decline of the Hollywood Studios, MOMA. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ a b Ware, Susan (2004). Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century. Harvard University Press. pp. 666–667. ISBN 978-0-674-01488-6.

- ^ "Colored Actresses Reap Fortunes In Maid Roles". Jet: 60–61. October 16, 1952.

- ^ Courtney, Susanm "Picturizing Race: Hollywood's Censorship of Miscegenation and Production of Racial Visibility through Imitation of Life". Archived May 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Genders, Vol. 27, 1998. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ Ronald Bergen. "Between Black and White", The Guardian (Manchester, UK), July 9, 1994.

- ^ Barbara Dianne Savage, Broadcasting Freedom, University of North Carolina Press, 1999, p. 172.

- ^ Fredi Washington. "Future for Negro Performers This Season Looks Very Dark," Atlanta Daily World, September 23, 1940, p. 2.

- ^ Earl Conrad; "Pass or Not To Pass?" (June 16, 1945), The Chicago Defender.

- ^ People's Voice, Historical Society of Philadelphia, 2005. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Petty, Miriam J. (2016). Stealing the Show: African American Performers and Audiences in 1930s Hollywood. Univ of California Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-520-96414-3.

- ^ "New York Beat". Jet: 63. November 6, 1952.

- ^ Davis, Kimberly N. (May 2006). "Fredi Washington: Black entertainers and the "Double V" campaign". Texas State University.

- ^ Finlay, Nancy (February 22, 2017). "Remembering Fredi Washington: Actress, Activist, and Journalist". Connecticut History.

- ^ "Veteran Actress Fredi Washington Dies At 90". Jet: 53. July 18, 1994.

- ^ Gilbert, Valerie C. (September 27, 2021). Women and Mixed Race Representation in Film: Eight Star Profiles. McFarland. ISBN 9781476644738 – via Google Books.

External links

edit- Fredi Washington at IMDb

- Fredi Washington at the Internet Broadway Database

- The People's Voice Research and Editorial Files (1865-1963) are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Erin Blakemore, "The Fair-Skinned Black Actress Who Refused to 'Pass' in 1930s Hollywood", History, January 26, 2021.