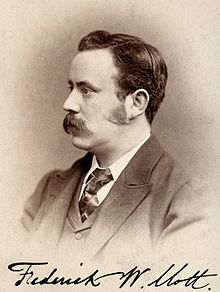

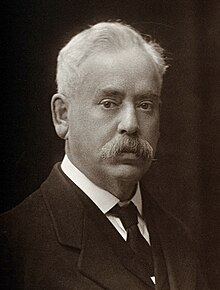

Sir Frederick Walker Mott KBE FRCP FRS (23 October 1853 in Brighton, Sussex – 8 June 1926 in Birmingham, Warwickshire) was one of the pioneers of biochemistry in Britain.[1] He is noted for his work in neuropathology and endocrine glands in relation to mental disorder, and consequently as a psychiatrist and social scientist. He was Croonian Lecturer to the Royal College of Physicians for the year 1900.[2]

The Maudsley Hospital in London was Mott's idea, inspired by Emil Kraepelin's clinic in Germany, and Mott conducted the negotiations for its funding and construction. He ran the pathology laboratory which was transferred there, and treated shell shock patients during World War I. His reputation had been greatly enhanced by helping establish that 'general paralysis of the insane' was actually due to syphilis, but he has been criticised for overly organic and degenerative assumptions in regard to mental illness including shell shock.[3]

After the war, in a lecture to the Eugenics Education Society, he claimed that shell shock was rare in volunteers as opposed to regular conscripted men, and that it was not a new disorder but merely a variation occurring in those already predisposed.[4]

Mott, like Maudsley, appears to have held that mental illness was inherited due to degenerate family lines that worsened until dying out, though his selecting of cases and statistics were questioned by other eugenicists.[5]

Mott advanced an overarching theory that mental disease was due to pathology of the sexual reproductive system, as evidenced for example by atrophied testes, causing breakdown of cerebral neurons in certain parts of the brain.[6][7]

Timeline

edit- 1884 Lecturer in physiology at the Charing Cross Hospital Medical School

- 1895 Director of the London County Council laboratory at Claybury Asylum.[8]

- 1896 Fellow of the Royal Society[9]

- 1909–12 Fullerian Professor of Physiology and Comparative Anatomy

- 1910 The Brain And The Voice In Speech And Song

- 1911 Awarded Fothergill Gold Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine[10]

- 1916 The Effects of High Explosives Upon the Central Nervous System The Lancet 1 (1916): 331–338

- 1919 Knighthood

- 1923 The Action of Alcohol on Man (London, New York: Longmans Green) with Ernest Henry Starling (1866–1927), Robert Hutchison (1871–)

- 1925–26 President of the Medico-Psychological Association

- 1926 President of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association, the Royal Charter having been granted in March 1926

References

edit- ^ Patron of the Royal Institution. Johnmadjackfuller.homestead.com. Retrieved on 8 June 2014.

- ^ "MOTT. Frederick Walker". Who's Who. 59: 1266. 1907.

- ^ 'An atmosphere of cure': Frederick Mott, shell shock and the Maudsley, kcl.ac.uk. Accessed 11 January 2023.

- ^ Shell Shocked Britain: The First World War's Legacy for Britain's Mental Health, books.google.com. Accessed 11 January 2023.

- ^ THE SO-CALLED LAW OF ANTICIPATION IN MENTAL DISEASE, 1933.

- ^ Evans, B.; Jones, E. (29 May 2012). "Organ extracts and the development of psychiatry: hormonal treatments at the Maudsley Hospital 1923-1938". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 48 (3): 251–76. doi:10.1002/jhbs.21548. PMC 3594693. PMID 22644956.

- ^ International Relations in Psychiatry: Britain, Germany, and the United States to World War II, books.google.com. Accessed 11 January 2023.

- ^ Frederick Mott biography. Studymore.org.uk. Retrieved on 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Notes". Nature. 54 (1389): 133–137. 1896. Bibcode:1896Natur..54..133.. doi:10.1038/054133a0.

- ^ "Sir Frederick Walker Mott". Royal College of Physicians. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

External links

edit- Works by Frederick Walker Mott at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Frederick Walker Mott at the Internet Archive

- Works by Frederick Walker Mott at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)