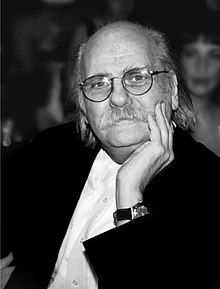

Frederick Delano Newman (June 17, 1935 – July 3, 2011)[1] was an American psychotherapist and left-wing political activist.

Newman and Lois Holzman created a therapeutic modality, Social Therapy.[2][3] Newman insisted "that there was nothing wrong with psychotherapists having sex with patients".[1]

Along with Lenora Fulani, Newman controlled several socialist and progressive political, therapy, and dramatic collective groups across the USA. These groups promoted "friendosexuality", which encouraged members to sleep with each other.[1][4] Newman strongly objected to the classification of these groups as a "cult", and argued that "there is no such thing as a cult".[5]

Because Newman's organizations frequently changed names,[4] followers of Newman have been called Newmanites[5] or the Newman Tendency.[4]

Personal life

editNewman was born in 1935 in The Bronx of New York City. Newman grew up in a working-class neighborhood. He served in the US Army, including a stint in Korea. Then, he attended the City College of New York under the GI Bill. In 1962, he earned a Ph.D. in analytic philosophy and in foundations of mathematics from Stanford University. Newman taught at several colleges and universities in the 1960s, including the City College of New York, Knox College, Case Western Reserve University, and Antioch College.

Newman was twice married and divorced. He had two children, Donald Newman and Elizabeth Newman. He was survived by his two life partners, Gabrielle L. Kurlander and Jacqueline Salit, in what Ms. Salit described as an "unconventional family of choice".[1][6]

Therapeutic theories and work

editNewman and his primary collaborator, Lois Holzman, challenged what they described as the "hoax/myth of psychology," the various components of which were termed "destructive pieces of pseudoscience."[7] In its place, they argued for a theory called "social therapy".

Social therapy

editThis section possibly contains original research. (September 2016) |

Social therapy is characterized as "revolution for non-revolutionaries."[8] In addition to Marx, it uses the insights of Vygotsky and Wittgenstein. It seeks to enlist "patients" in the collective work of constructing new environments that challenge the commodification of emotionality, and re-ignite human development.

The Practice of Method, is the seminal written work on social therapy, the first published formulation by Newman and his colleagues of a Marxist approach to therapy. Social therapy came, in later years, to be influenced by other thinkers (notably Vygotsky and Wittgenstein) and other therapeutic approaches (notably cognitive behavioral therapy). The Practice of Method exposes the roots of social therapy. It is the beginning of a continuing investigation of method in the study of human growth and development, to which Newman (together with his chief collaborator, Lois Holzman) returns again and again in his later work.

"Undecidable Emotions (What is Social Therapy? And How Is it Revolutionary?)" (Newman, 2003, Journal of Constructivist Psychology) seeks to illuminate a revolutionary approach to group therapy by an appeal to – of all things – twentieth century discoveries in science and mathematical logic.

"All Power to the Developing'" (Newman & Holzman, 2003, Annual Review of Critical Psychology) examines the two Marxist notions, class struggle (The Communist Manifesto) and revolutionary activity (Theses on Feuerbach).

Marxism, influences, and views

editNewman considered himself a Marxist,[9] a philosophy that he incorporated into his therapeutic approach in an attempt to address the alienating effects of societal institutions on human development. In his earliest statement of his attempt to develop a Marxist approach to emotional problems, Newman wrote in 1974:

Proletarian or revolutionary psychotherapy is a journey which begins with the rejection of our inadequacy and ends in the acceptance of our smallness; it is the overthrow of the rulers of the mind by the workers of the mind.[10]

Later, Newman incorporated other influences, including the 20th-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and Aleksey Leontyev and Sergei Rubinshtein's activity theory, and the work of early Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky.[11][12]

Playwriting, theater, and social therapy

editNewman was a cofounder (1983),[13] artistic director (1989–2005), and playwright-in-residence of the Castillo Theatre in New York.[14] The theater, named for the Guatemalan poet Otto René Castillo, has served as the primary venue for the production of the 30 plays that Newman wrote since the 1980s, four of which were written for and performed at annual conventions of the American Psychological Association from 1996 onwards.[15] Newman described the Castillo Theatre as a "sister" organization to his social therapy clinics and institutes, where he also used Vygotsky's methodological approach.[16] Writing in 2000 in New Therapist, Newman and Holzman discussed the Vygotskian thread that linked the sister organizations:[17]

The entire enterprise - human life and its study - is a search for method. Performance social therapeutics, the name we use to describe our Marxian-based, dialectical practice, originated in our group therapy but is also the basis for a continuously emergent development community.

We coined the term tool-and-result methodology for Vygotsky's (and our) practice of method in order to distinguish it from the instrumental tool for result methodology that characterizes the natural and social sciences (Newman and Holzman, 1993). Our community building and the projects that comprise it - the East Side Institute for Short Term Psychotherapy, the East Side Center for Social Therapy and affiliated centers in other cities, the Castillo Theatre, the All Stars Talent Show Network, the Development School for Youth, etc. - are practices of this methodology.

The Castillo and its parent charity, the All Stars Project, Inc., supported Newman's therapeutic endeavors, such as a number of supplementary education programs for youth, including the Joseph A. Forgione Development School for Youth.[18]

On December 6, 2005, Newman announced his retirement as the Castillo's artistic director in the wake of controversy over a six-part series the previous month on NY1 News (a cable television news channel). In a letter to the All Stars Project's Board of Directors, Newman explained that he did not "want any of the controversy associated with my views and opinions to create unnecessary difficulties for the All Stars Project."[19] The cable program contained segments of an interview in which Newman discussed his longstanding opposition to having his therapeutic approach being governed by the American Psychological Association's ethical guidelines, notably those prohibiting sexual relations with patients.[20]

Anti-semitism allegations

editSome of Newman's plays have been cited as examples of alleged anti-Semitism by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL),[21] which Newman described as "politically motivated".[22] In his play No Room for Zion (1989), Newman recounts the transition in his own Bronx Jewish community from primarily working class to increasingly middle class and upwardly mobile, rapidly losing its identity as an immigrant community tied to traditional ideals (represented by the Rabbi Zion of the play's title). In the play, Newman goes on to present his view of the postwar shifts in Jewish political alignments, both domestically and internationally:

From the West Bank to the West Side of Manhattan, international Jewry was being forced to face its written-in-blood deal with the capitalist devil. In exchange for an unstable assimilation, Jews under the leadership of Zionism would "do-unto-others-what-others-had-done-unto-them." The others to be done unto? People of color. The doing? Ghettoization and genocide. The Jew, the dirty Jew, once the ultimate victim of capitalism's soul, fascism, would become a victimizer on behalf of capitalism, a self-righteous dehumanizer and murderer of people of color, a racist bigot whom in the language of Zionism changed the meaning of "Never Again" from "Never Again for anyone" to "Never again for us – and let the devil take everyone else.

The ADL also criticized the Newman's 2004 play, Crown Heights, which was based on the 1991 riots sparked by the accidental death of a black child who was struck and killed by the motorcade of a prominent local rabbi. The ADL claimed that the production "distorts history and refuels hatred."[23] One reviewer considered the production to be one that "seeks to unite the city's diverse youth and heal some of the wounds of past racial violence."[24]

Political organizations

editCenters for Change

editNewman founded the collective Centers for Change (CFC) in the late 1960s after the student strikes at Columbia University.[25] CFC was dedicated to 1960s-style, radical community organizing and the practice of Newman's evolving form of psychotherapy, which he would term around 1974 "proletarian therapy" and later "Social Therapy."[26] CFC briefly merged with Lyndon LaRouche's National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC) in 1974, but a few months, the alliance fell apart, an event that Newman attributed to LaRouche's increasingly "paranoid" and "authoritarian" direction[27] and to the NCLC's "capacity to produce psychosis and to opportunistically manipulate it in the name of socialist politics."[28]

International Workers Party

editIn August 1974, the CFC went on to found the International Workers Party (IWP), a revolutionary party that was explicitly Marxist-Leninist. In the wake of another factional fight in 1976, the IWP publicly disbanded. In 2005, Newman told The New York Times that the IWP had transformed into a "core collective" that still functions.[29] That claim appears to be consistent with critics who had alleged several years earlier that the organization had never actually disbanded and remained secretly active.[5][30][31]

Throughout the late 1970s, Newman and his core of organizers founded or assumed control of a number of small grassroots organizations, including a local branch of the People's Party, known as the New York Working People's Party; the New York City Unemployed and Welfare Council; and the Labor Community Alliance for Change.[32][33]

New Alliance Party

editIn 1979, Newman became one of the founders of the New Alliance Party (NAP), which was most notable for getting African-American psychologist and activist Lenora Fulani on the ballot in all 50 states during her 1988 presidential campaign, making her the first African-American and the first woman to do so. Newman served primarily as the party's tactician and campaign manager. In 1985, Newman ran for Mayor of New York. He also ran for US Senator that year and for New York State Attorney General in 1990.[citation needed]

Independence Party of New York

editAfter the New Alliance Party was dissolved in 1994, a number of its members and supporters, including Newman and Fulani, joined the Independence Party of New York (IPNY). It had been founded by activists in Rochester, New York in 1991 but became more important in other parts of the state after the rise of Ross Perot's Reform Party.

In September 2005, the New York State Executive Committee of the Independence Party, under the leadership of IPNY State Chairman Frank MacKay, voted to remove Fulani and several other members. In a letter proposing the matter for vote, MacKay stated Fulani et al. had created the perception that the IPNY leadership tolerated "bigotry and hatred" and had "continually re-affirmed their disturbing social commentary in the state and national press."[34]

A later petition by MacKay to have Fulani and Newman, among others, disenrolled from the party was entirely dismissed by the New York Supreme Court in both Brooklyn and Manhattan. Manhattan Justice Emily Jane Goodman wrote that "the statements attributed to Fulani and Newman which many would consider odious and offensive were made by them in 1989 and 1985, respectively, and not in their capacity as Independence Party members or officers in the Party which did not even exist at the time." Goodman noted the timing of the petition appeared "more political than philosophical." More to the point, however, the petitioned grounds for disenrollment were ruled invalid because "there are no enunciated standards or requirements for persons registering in the Party."[35] As a result, Newman and Fulani were not removed.

New York City municipal bonds

editNewman strongly encouraged the Independence Party to support Republican candidate Michael Bloomberg in 2001, 2005, and 2009.[1]

In 2002, the New York City Industrial Development Agency (with agreement by the state) approved an $8.5 million bond to help finance a new headquarters for a youth charity controlled by Newman and Lenora Fulani, Newman's chief spokesperson and a prominent Independence Party public figure.[36] The media characterized approval of the bond as a reward from Mayor Bloomberg and as well as an incentive by Governor George Pataki to obtain Newman and Fulani's support for his re-election campaign.[1]

In 2003, the Institute for Minority Education of Columbia University's Teachers College undertook an evaluation of All Stars programs, which was coordinated and funded by All Stars Project staff and supporters.[37] The 124-page report was based on extensive on-site observation of two of the All Stars programs, which were described as "an exemplary effort in a field that is bursting with creative activity". The authors noted that they had "not had access to data referable to the impact of these interventions on the short or long term behavioral development of learner participants".[38] The report made only one brief reference (on page 9) to controversies regarding All Stars staff and volunteers being "involved in various political movements, most centrally Independent [sic] Party politics ... [w]hile sometimes used as a point of attack by unfriendly media, the political networking has given the All Stars Project access to some halls of power that would have otherwise been closed." The Columbia researchers noted on page 14 of their report praised the political character of the All Stars program: "Although political activism is not an explicit part of the All Stars and the DSY curriculum, it is an outcome of the programs. Young people who are empowered to get what they want are also likely to fight for what they think is right ... [T]he participants and staff of the ASTSN/DSY (All Stars Talent Show Network/Development School for Youth) have developed policy approaches to working with youth that are practical, efficient, and successful. That they have also worked to develop some influence in the halls of power is a tremendous asset to the development of the programs—as well as to the political process, which needs all the direction it can get in developing and implementing policy."[38]

In 2006, the New York City Industrial Development Agency performed a review of the All Stars pursuant to an All Stars application for a bond. Several Democratic Party officials expressed strong opposition. Critics of the IDA bond, including New York State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, charged that the All Stars were connected to "leaders who have taken positions that are misogynistic and Anti-Semitic", and questioned whether Newman and Fulani still ran All Stars, despite their having stepped down from official positions.[39]

Despite public criticisms, the IDA board voted 6 to 4 in favor of approving the bond. All those in favor were mayoral appointees or representatives of ex officio members who were mayoral appointees. All those opposed were representatives of the offices of the Borough Presidents of Manhattan, the Bronx, and Queens, as well as the office of then-New York City Comptroller William C. Thompson Jr..[40]

After the vote, IDA chairman Joshua J. Sirefman told reporters that, based on the IDA's review of the All Stars Project, "[w]e have determined that the organization is in good standing, we found no evidence of misconduct of any kind by the organization, and we established that the project would benefit New York City... We are aware that allegations of wrongdoing by individuals associated with the organization existed a number of years ago."[41][42]

In subsequent news coverage, Mayor Michael Bloomberg defended the Agency's vote to approve the bonds, noting "I don't think I heard one argument made that there was something wrong with the All Stars Project and that's what we look at."[43]

Cult allegations

editEarly "therapy cult" allegations

editIn 1977, an article by Dennis King in Heights and Valley News alleged Newman was the leader of a "therapy cult".[44] The Public Eye magazine also carried an article in late 1977 making the claim, but it was primarily directed at Lyndon LaRouche's NCLC (with which Newman was no longer affiliated).[45]

In 1977, Newman responded that "it is of the greatest importance that the entire community of social scientists insist that there be open and critical discussion and dialogue towards the advancement and development of the human sciences; that as scientists and as professionals we do not quiver and shake under the socio-pathological and essentially anti-communist rampages of a Dennis King or others like him."[46]

Cult allegations arose again a 1982 article in the Village Voice.[47]

When political researcher Chip Berlet became editor of The Public Eye magazine in 1984, he announced that the magazine no longer held to that characterization:[48]

As you will learn from a forthcoming article on Fred Newman and the IWP, the Public Eye no longer feels it is accurate to call Newman's political network a cult. We do feel that at one point in its development it was fair to characterize the group as a cult, and we still have strong criticisms of the group's organizing style and the relationship between Newman's Therapy Institute and his political organizing.

In 1988, a special issue of Radical America carried a series of articles and essays alleging manipulation, political deceit, and cult-like practices within the NAP. While Berlet, who had contributed to the issue, noted that Fulani "deserves tremendous credit for apparently gaining ballot status in a majority of states," the editors concluded that there were "dangerous ... implications" in failing to confront Newman and his groups: "Painful and unpleasant as it is, the time has come to expose the NAP before it discredits the Left – especially among blacks, gays and those exploring progressive politics for the first time."[49]

A former NAP campaign worker, Loren Redwood, gave a much more critical account of her experiences with the party in a 1989 letter to the editor of Coming Up!, a lesbian and gay newspaper published in San Francisco. In the letter, Redwood describes her falling in love with a NAP campaign worker and the difficulties she encountered after joining her lover on the road campaigning for Fulani:[citation needed]

NAP claims to be a multi-racial, black led, woman led, pro gay, political party, an organization which recognizes and fights against racism, sexism, classism and homophobia – but NAP is a lie. NAP is always using the slogan: "the personal is political" and emphasizing the importance of enacting one's politics into daily life. But this vision and the way their politics are enacted within the organization and life of those working for them is very much in conflict. As a working class lesbian, I thought I had finally found a political movement which included me. What I found instead was an oppressive, disempowering, misogynistic machine. All my decisions were made for me by someone else. I was told where to go, and who to go with.

I worked seven days a week – 16 to 20 hours a day (I had two days off in 2.5 months). There was an incredible urgency which overrode any personal needs or considerations, an urgency that meant complete self-sacrifice. I realize now how sexist that is. As a woman, I have always been taught that self-sacrifice is good and that I must be willing to give up everything for the greater good for all. Traditionally, this has come in the form of a husband and children; NAP is simply a substitute. I felt totally powerless over my life, forced into a very submissive role where all control of my life belonged to someone else.

In 1989, Newman told The New York Times that his critics were "being sectarian and refusing to recognize the extraordinary accomplishments" of Fulani and the NAP leadership.[50]

Interviewed in the Times in 1991, Newman described the criticisms as "absurd" and the product of jealousies on the left and claimed that most social therapy clients do not involve themselves in his political activities.[51] In the Boston Globe in 1992, Fulani claimed "the entire thing is a lie" and cited what she described as Political Research Associates' ties to the Democratic Party.[citation needed]

Sympathetic therapeutic professionals

editSome of the cult criticisms have been disputed by some of Newman's therapist peers.[52]

According to British psychologist Ian Parker, "Even those [Newman and Holzman] who have been marked by the FBI as a 'cult' may still be a source of useful radical theory and practice. Like a weed, a cult is something that is growing in the wrong place. We would want to ask 'wrong' for who, and whether it might sometimes be right for us. We have no desire to line up with the psychological establishment to rule out of the debate those who offer something valuable to anti-racist, feminist or working-class practice."[53]

2003 interview with John Soderlund

editNewman (along with Holzman) responded to the ongoing controversy in a 2003 interview with John Söderlund, the editor of New Therapist, in a special issue devoted to mind control.[54] In her introduction to the responses, Holzman claimed that the editor's questions "have that 'When did you stop beating your wife?' quality":

These kinds of attacks are ludicrous in the way that the charge of being a witch was in centuries past. A cult is a made-up thing for which (like the made-up witch) there is no falsifiability. An entire mythology can thus be created, complete with attributes and activities that cannot be proven or disproven. Indeed, that's the virtue of such made-up things. They paint a picture that holds you captive.

Söderlund asked about the recent focus of the American Psychological Association on the "potential dangers of mind control."

Newman replied that he did not quite know what was meant by the term and noted, "The closest association I have to it is what happens between parents and their young children. When children are very young, parents create a very controlled environment where there's a great level of dependency on the parents. Gradually, as children come to experience other kinds of institutions (day care, school, etc.) their lived environment becomes less controlled and their dependency lessens." He explained that he did not think that sort of "totally controlled environment" to be imposable on an adult relationship "outside of the extraordinary circumstances of say, the Manchurian Candidate. I don't see how mind control has any applicability to therapy—therapy of any kind—as it's a relationship where the clients have control.... They pay, they can not show up, etc." Newman acknowledged that he believed that authoritarian and coercive therapists were likely doing bad therapy, but he did not consider that to be mind control.[54]

Söderlund asked Newman to respond to an anonymous former social therapist's statement that the practice has "the criteria of groups which are considered cults: an authoritarian, charismatic leader, black-and-white thinking, repression of individuality, constant drive for fundraising, control of information, lack of tolerance for opposition within the group, etc."

Newman claimed he did not know what a cult was or even if there was such a thing and that the use of the cult charge is "hostile, mean-spirited, and destructive." He denied being "authoritarian," acknowledged the perception that he was "charismatic," and considered the claim of "black-and-white thinking" to be "antithetical to everything we do" and cited social therapy's interactions "with practitioners and theorists across a very wide spectrum of traditions and worldviews." Newman countered the charge by insisting, "We don't repress individuality; we critique it. There is a difference!" Newman commented as well on charges that he "held in contempt" ethical guidelines of professional associations such as the APA: "We don't look to the APA, CPA or any other institution for ethical standards," he replied. "We're critical (not contemptuous) of them for being hypocritical and think that depending on them for an ethical standard is ethically unsound."[54]

Newman, et al. vs the FBI

editFBI documents obtained in 1992 by the Freedom of Information Act showed that during Fulani's 1988 campaign for president, it had begun a file that classified her party as a "political cult" that "should be considered armed and dangerous." As described by investigative reporter Kelvyn Anderson in the Washington City Paper in 1992, "The 101-page FBI file, freed by an FOIA request, also contains media coverage of Fulani's 1988 campaign, memos between FBI field offices on the subject of the New Alliance Party, a letter from an army counterintelligence official about party, and a copy of Clouds Blur the Rainbow, a report issued in late 1987 by Chip Berlet of Political Research Associates (PRA). PRA, which studies fringe political groups and intelligence agency abuses, is a prominent critic of the NAP, and its research is frequently used to discredit NAP as a psycho-political cult with totalitarian overtones."[55]

Newman, Fulani, and the New Alliance Party challenged the FBI in a 1993 lawsuit asserting the FBI "political cult" labeling had violated their constitutional rights. The plaintiffs asserted that the bureau was gathering information from private, third-party organizations to evade federal guidelines prohibiting investigations of political organizations in the absence of evidence of criminal activity. In their suit, Newman et al. argued:

Political intelligence reports like [the ADL's 1990 report] The New Alliance Party and [PRA's] Clouds Blur the Rainbow, could not constitutionally be funded by the FBI directly. Organizations like the ADL and PRA engage in political intelligence gathering and political attacks on plaintiffs which the defendants are barred from carrying out directly by the Guidelines. The FBI then distributes the results of those "private" studies to its agents, and gives credibility to the "private" findings by incorporating the reports into files that are then obtained through FOIA by journalists and others[56]

In her ruling on the case, Federal Judge Constance Baker Motley ruled that the "political cult" charge "could not be directly traced to the 1988 FBI investigation" and that "any stigmatization which NAP suffers could be traced to a myriad of statements and publications made by private individuals and organizations, many of which preceded the FBI investigation.[56]

Berlet, while upholding the charge of cultism, was critical of the FBI by noting that its investigation was "not a protection of civil liberties but a smear of a group."[57]

2004 Presidential election

editThe cult charges appeared again in the 2004 Presidential election, when Newman supported independent presidential candidate Ralph Nader.

The Nation magazine, a leading liberal weekly which had supported Nader in 2000, asked, citing Berlet's report, "what in the world is Ralph Nader doing in bed with the ultrasectarian cult-racket formerly known as the New Alliance Party?"[58][59]

In its introduction to an article later that year by political writer Christopher Hitchens, the magazine Vanity Fair noted, "Democrats are furious that Ralph Nader, whose last presidential bid helped put George W. Bush in office, is running again. Equally dismaying, the author finds, is Nader's backing from a crackpot group with ties to Pat Buchanan, Lyndon LaRouche, and Louis Farrakhan." Echoing Berlet (who had attacked Nader in 2000 for working with figures like conservative industrialist Roger Milliken), Hitchens charged that "[t]he Newman-Fulani group is a fascistic zombie cult outfit."[58]

Nader came under fire from the ADL that year for his own Middle East views.[60]

Later evaluations

editIn 2007, social psychologist and cult survivor Alexandra Stein wrote a dissertation for the University of Minnesota about the Newman "operation". Arguing that it was a cult, Stein stated that members were recruited by therapy sessions and then controlled with fear.[61] Exhausted by overwork and constant crisis, members clung to the organization and its charismatic leader for safety. According to Stein, a member named Marina Ortiz fled only after the group instructed her to put her son in foster care.[62]

In 2017, Stein summarized Newman's "operation" as a "totalist system":[4]

Gradually, they abandoned outside jobs and worked for the group, often off the books. They shared apartments, attended meetings late into the night, and restricted relationships with outsiders. Instead, many were set up in casual sexual relationships with other followers in a practice called ‘friendosexuality’. They were also assigned a ‘friend’ whose role was to monitor and criticise to keep them in line. Those with money were soon parted from it. Some women in the group were told by Newman to have abortions, and few had children while involved.

Publications

editThis article lacks ISBNs for the books listed. (July 2011) |

- Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (in press). All Power to the Developing. To appear in the Annual Review of Critical Psychology.

- Holzman, L. and Newman, F. (2004). Power, authority and pointless activity (The developmental discourse of social therapy.) In T. Strong and D. Paré (Eds.), Furthering talk: Advances in the discursive therapies . Kluwer Academic/Plenum, pp. 73–86.

- Newman, F. (2003). Undecidable emotions (What is social therapy? And how is it revolutionary?). Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 16: 215-232.

- Power, authority and pointless activity (The developmental discourse of social therapy).*Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (2001). La relevancia de Marx en la Terapeutica del siglo XXI. Revista Venezolana de Psicologia Clinica Comunitaria, No. 2, 47-55.

- Newman, F. (2001). Therapists of the world, unite. New Therapist. No. 16.

- Newman, F. (2001). Rehaciendo el pasado: Unas cuantas historias exitosas en materia de Terapia Social y sus moralejas. Revista Venezolana de Psicologia Clinica Comunitaria, No. 2, 57-70.

- Newman, F. (2000) Does a story need a theory? (understanding the methodology of narrative therapy). In D. Fee (Ed.) Pathology and the postmodern: mental illness as discourse and experience. London: Sage.

- Newman F. and Holzman, L. (2000). Against Against-ism. Theory & Psychology, 10(2), 265-270.

- Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (2000). Engaging the alienation. New Therapist, 10(4).

- Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (2000). The relevance of Marx to therapeutics in the 21st century. New Therapist, 5, 24-27.

- Newman, F. (1999). One dogma of dialectical materialism. Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 1. 83-99.

- Newman, F. and L. Holzman. (1999). Beyond narrative to performed conversation (in the beginning comes much later). Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 12, 1, 23-40.

- Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (1997). The end of knowing: A new developmental way of learning. London: Routledge.

- Newman, F. (1996). Performance of a lifetime: A practical-philosophical guide to the joyous life. New York: Castillo.

- Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (1996). Unscientific psychology: A cultural-performatory approach to understanding human life. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Newman, F. (1994). Let's develop! A guide to continuous personal growth. New York: Castillo International.

- Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (1993). Lev Vygotsky: Revolutionary scientist. London: Routledge.

- Newman, F. (1992). Surely Castillo is left but is it right or wrong? Nobody knows. The Drama Review. Fall (T135), pp. 24– 27.

- Newman, F. (1991). The myth of psychology. New York: Castillo International.

- Holzman, L. and Newman, F. (1979). The practice of method: An introduction to the foundations of social therapy. New York: New York Institute for Social Therapy and Research.

- Newman, F. (1977). Practical-critical activities. New York: Institute for Social Therapy.

- Newman, F. (1974). Power and authority: The inside view of the class struggle. New York: Centers for Change.

- Newman, F., assisted by Daren, Hazel (1974). A Manifesto on Method: A Study of the Transformation from the Capitalist Mind to the Fascist Mind. New York: International Workers Party.

- Newman, F. (1968). Explanation by description: An essay on historical methodology. The Hague: Mouton.

- Newman, F. (1982). Games the New Alliance Party Won't Play

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Martin, Douglas (July 9, 2011). "Fred Newman, Writer and Political Figure, Dies at 76". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 4, 2023.

- ^ Social Therapy Group website Archived 2006-08-10 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved October 2006

- ^ Holzman, L. (2004) Psychological Investigations: An Introduction to Social Therapy, a talk given at the University of California, Berkeley, as part of the UC system-wide Education for Sustainable Living Program.

- ^ a b c d Stein, Alexandra. "How Totalism Works". Aeon. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

Since the organization changes its name frequently, morphing as needed, culling elements and adding others, I refer to it here as the Newman Tendency. This uses one of its own names – The Tendency – while acknowledging the formative and central role of its charismatic and authoritarian leader, Fred Newman.

- ^ a b c Tourish, Dennis; Wohlforth, Tim (2000). On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765636409.

It should come as no surprise that Fred Newman, Lenora Fulani, and other spokespeople for the group do not share our assessment that they run a cult. In fact in 1993 they took legal action against the FBI for characterizing them as a "political/cult organization." 71 Lenora Fulani stated that "the word 'cult' is a weapon, a murderously vicious, anti-democratic weapon used to attack people who are different in any way: religiously, politically, culturally or otherwise.... There is no such thing as a cult [emphasis in original]." 72 At the time Fulani and Newman's lobbying arm, Ross and Green, was running a campaign in defense of the Branch Davidians after the Waco disaster.

- ^ "East Side Institute website". Eastsideinstitute.org. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ Nissen M, Axel E, Bechmann Jensen T. The Abstract Zone of Proximal Conditioning. Theory & Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 3, 417-426 (1999)

- ^ Newman, Fred; Holzman, Lois (2003). "All Power to the Developing!". Annual Review of Critical Psychology. 3: 8–23. ISSN 1464-0538. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Why I'm Still a Marxist, A Seminar with Fred Newman". Acteva.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ Fred Newman, Preface to Power and Authority: the Inside View of the Class Struggle (1974).

- ^ Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (1997). The end of knowing: A new developmental way of learning. London: Routledge.

- ^ Holzman L. Activating Postmodernism. Theory & Psychology, Vol. 16, No. 1, 109-123 (2006)

- ^ Brenner, Eva. (1992) Theatre of the Unorganized: The Radical Independence of the Castillo Cultural Center. The Drama Review. 36, 3:28–60.

- ^ Cook, Sean. Walking the Talk. Castillo Theatre of 2002. (2003). The Drama Review. 47, 3:78-98.

- ^ Theatre for the Whole City: the All Stars Project Performs New York City Archived 2006-10-04 at the Wayback Machine, All Stars Project, Inc.; accessed October 28, 2006

- ^ Newman, Fred. (1992). "Surely Castillo is left but is it right or wrong? Nobody knows." The Drama Review. Vol. 36, No. 3:24-27

- ^ Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (2000). "The relevance of Marx to therapeutics in the 21st century", New Therapist, 3, 24-27.

- ^ Institute for Urban and Minority Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. (2003) Changing the Script for Youth Development: An Evaluation of the All Stars Talent Show Network and the Joseph A. Forgione Development School for Youth, Education Resources Information Center, Institute of Education Sciences (IES), US Department of Education; accessed October 2006

- ^ "Newman resigns from All Stars Project", The New York Sun, December 7, 2005. Accessed online October 2006

- ^ "Psychopolitics: Inside The Independence Party Of Fred Newman". Ny1.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- ^ "A Cult By Any Other Name: The New Alliance Party Dismantled and Reincarnated". Adl.org. Archived from the original on 2013-01-04. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ Cook, Sean. Walking the Talk. Castillo Theatre of 2002: Newman vs. the Anti-Defamation League. (2003). The Drama Review 47, 3:78-98.

- ^ "ADL Says 'Crown Heights' Distorts History and Refuels Hatred" Archived 2006-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, ADL press release, January 27, 2004; accessed October 2006

- ^ Abby Ranger, "Youth Theatre, "'Crown Heights' Seeks to Soothe Racial Tensions", Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 26, 2004 All Stars article reproduced online Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, accessed October 24, 2006

- ^ CFC—A Collection of Liberation Centers. CFC Press. (1972)

- ^ Newman, Fred. Power and Authority: The Inside View of Class Struggle. Centers For Change (1974)

- ^ Fred Newman, assisted by Hazel Daren, A Manifesto on Method: A study of the transformation from the capitalist mind to the fascist mind, International Workers Party (1974); accessed online on ex-iwp.org, October 17, 2006

- ^ Fred Newman, An Open Letter to the NCLC (1974); accessed online on laroucheplanet.info, October 19, 2015

- ^ Slackman, Michael. "In New York, Fringe Politics in Mainstream", The New York Times, May 28, 2005

- ^ Berlet, Chip, 1987, Clouds Blur the Rainbow: The Other Side of the New Alliance Party, Cambridge, MA: Political Research Associates

- ^ "Fred Newman bibliography". Publiceye.org. 1987-11-27. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ Harvey Kahn, "NCLC: America's Largest Political Intelligence Army", Public Eye, Vol 1., No. 1, Fall 1977, pp. 6-37; see section on "NCLC and Its Extended Political 'Community'"

- ^ Chip Berlet, 1987, Clouds Blur the Rainbow: The Other Side of the New Alliance Party, Cambridge, MA: Political Research Associates

- ^ "IPNY.org". IPNY.org. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ [1] Archived November 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rothacker, Rick (May 26, 2003). "Activist urges bank to cut ties to N.Y. group". Charlotte Observer.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ All Stars Project. Report from the president. Vol 5, No. 3, June, 2002.

- ^ a b Institute for Urban and Minority Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. (2003). Changing the Script for Youth Development: An Evaluation of the All Stars Talent Show Network and the Joseph A. Forgione Development School for Youth. Available at Eric.ed.gov; accessed October 2006

- ^ "OSC.state.ny.us". OSC.state.ny.us. 2006-09-11. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ "NYsun.com". NYsun.com. 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (2006-09-13). "Bloomberg quote at New York Times online". New York City: Select.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ "New York Sun online report re Newman". Nysun.com. 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ "website". Ny1.com. 2006-09-13. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ^ King, Dennis. West Side "Therapy Cult" Conceals Its True Aims. Heights and Valley News, November 1977

- ^ Harvey Kahn, "NCLC: America's Largest Political Intelligence Army," The Public Eye, Vol 1, No. 1, Fall 1977, pp. 6-37

- ^ Newman, Fred. Matter Over Mind. Vol. 1, No. 1, December 1977

- ^ Conason, Joe. Psycho-Politics: What Kind of Party Is This, Anyway? Village Voice. June 1, 1982.

- ^ Editor's Note, Public Eye, 1984; Vol. 4, Nos. 3-4

- ^ "Introduction, Radical America, pg. 3

- ^ Party, Described as Cult, Seeks Role in Primary. The New York Times. September 9, 1989

- ^ Street-Wise Impresario; Sharpton Calls the Tunes, and Players Take Their Cues. The New York Times. December 19, 1991

- ^ Nissen M et al. Theory & Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 3, 417-426 (1999)

- ^ Parker, I. (1999) "Critical Psychology: Critical Links", Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 1, pp. 3-18. Radpsynet.org

- ^ a b c "Culture shock." New Therapist 24 (March/April 2003)

- ^ Anderson, Kelvyn. Capitolism: The FBI's Spying Campaign against Candidate Lenora Fulani's New Alliance Party. Washington City Paper, March 6, 1992

- ^ a b New Alliance Party vs. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 93 CIV 3490 (1993)

- ^ Anderson, Kelvyn. "Capitolism: The FBI's Spying Campaign against Candidate Lenora Fulani's New Alliance Party". Washington City Paper, March 6, 1992

- ^ a b Hitchens, Christopher. Unsafe On Any Ballot Vanity Fair, May 2004

- ^ Ireland, Doug. "Nader and the Newmanites", The Nation. January 26, 2004

- ^ Faler, Brian. "Nader vs. the ADL". Washington Post, August 12, 2004

- ^ Stein, Alexandra (2007). Attachment, Networks and Discourse in Extremist Political Organizations: A Comparative Case Study (PDF) (Thesis). University of Minnesota. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2021.

- ^ Stein, Alexandra (2016). Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachment in Cults and Totalitarian Systems. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781138677951.

External links

editThis article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (September 2016) |

Newman-related websites

edit- Eastside Institute for Group and Short-term Psychotherapy

- Lois Holzman

- Performing the World

- The Social Therapy Group

- Life Performance Coaching Center

- Atlanta Center for Social Therapy

- All Stars Project

- Castillo Theatre

- Committee for a Unified Independent Party Archived 2005-12-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Independent Voting

Newman's critics

edit- Studies on Newman from Political Research Associates; PRA claims to "expose movements, institutions, and ideologies that undermine human rights". Contains only anti-Newman reports.

Response to critics

edit- Fred Newman and his Critics from official website