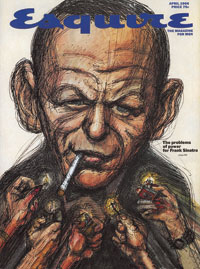

"Frank Sinatra Has a Cold" is a profile of Frank Sinatra written by Gay Talese for the April 1966 issue of Esquire.[1] The article is one of the most famous pieces of magazine journalism ever written and is often considered not only the greatest profile of Frank Sinatra[2] but one of the greatest celebrity profiles ever written.[3][4][5] The profile is one of the seminal works of New Journalism and is still widely read, discussed and studied.[6][7] In the 70th anniversary issue of Esquire in October 2003, the editors declared the piece the "Best Story Esquire Ever Published".[1][8] Vanity Fair called it "the greatest literary-nonfiction story of the 20th century".[4] The illustrations that accompanied the original article were made by Edward Sorel, who also did the artwork for the Esquire issue's front cover.[9]

Assignment

editTalese had spent the first ten years of his career at The New York Times. He felt restricted by the limitations of newspaper writing[4] and began searching for jobs with magazines. In 1965, he signed a one-year, six-story contract with Esquire magazine.[7] His first assignment from Esquire editor Harold Hayes was to write a profile of Frank Sinatra. It was a difficult assignment; Sinatra had turned down interview requests from Esquire for years.[3]

Sinatra, about to turn 50, was in the spotlight. His relationship with 20-year-old Mia Farrow was constantly in the news. A CBS television documentary had upset Sinatra, who felt that his life was being pried into, and he was unhappy about speculation in the documentary about his connection to Mafia leaders. He was also worried about his starring role in an upcoming NBC show named after his album, A Man and His Music, and his various business ventures in real estate, his film company, his record label, and an airline. At the time, Sinatra maintained a personal staff of 75.[1]

Sinatra refused to be interviewed for the profile.[4][7] Rather than give up, Talese spent three months, beginning in November 1965, following Sinatra and observing everything he could and interviewing any members of his entourage who were willing to speak.[6] Esquire paid nearly $5,000 in expenses over the duration of the story.[3] Talese was uncertain whether the story could be finished, but ultimately concluded, in a letter to Hayes, that "I may not get the piece we'd hoped for—the real Frank Sinatra, but perhaps, by not getting it—and by getting rejected constantly and by seeing his flunkies protecting his flanks—we will be getting close to the truth about the man."[4] Without Talese ever receiving Sinatra's cooperation, the story was published in April 1966.

Profile

editThe profile begins with Sinatra in a sullen mood at a private Hollywood club. Stressed about all the events in his life, Sinatra, and many of his staff, are in a poor mood because Sinatra is afflicted by the common cold, hampering his ability to sing. The significance of the cold is expressed by Talese in one of the story's most famous passages:[4]

Sinatra with a cold is Picasso without paint, Ferrari without fuel—only worse. For the common cold robs Sinatra of that uninsurable jewel, his voice, cutting into the core of his confidence, and it affects not only his own psyche but also seems to cause a kind of psychosomatic nasal drip within dozens of people who work for him, drink with him, love him, depend on him for their own welfare and stability. A Sinatra with a cold can, in a small way, send vibrations through the entertainment industry and beyond as surely as a President of the United States, suddenly sick, can shake the national economy.[1]

The style of narrative writing, in this passage and throughout the piece, was alien to journalism at the time, and was considered the province of fiction writing.[6] Only a few other authors, such as Tom Wolfe, were using such techniques in journalistic writing. The piece employed techniques like scenes, dialogue and third-person narrative that were common in fiction, but still rare in journalism.[7]

While Sinatra was near the heights of his fame in the 1960s the world of music was changing. The arrival of bands like the Beatles and the accompanying cultural change was threatening to Sinatra.[4] This is illustrated in a scene with the writer Harlan Ellison who is wearing corduroy slacks, a Shetland sweater, a tan suede jacket, and Game Warden boots while playing pool in a club. Sinatra confronts and questions Ellison about his boots. Ellison, annoyed by Sinatra's questions, rebuffs him. After Ellison leaves the room, Sinatra tells the assistant manager, "I don't want anybody in here without coats and ties."[1]

Though never speaking with Sinatra, Talese cast light on the singer's mercurial personality and internal turmoil. The story also detailed Sinatra's relationship with his children and his former wives, Nancy Barbato and Ava Gardner. Through a series of scenes and anecdotes, focusing on the people surrounding Sinatra, the article "reveals the inner workings of the climate-controlled biosphere the singer had constructed around himself—and the inhospitable atmosphere coalescing outside its shell."[4]

The article ends with a passage indirectly demonstrating Sinatra's unquenchable thirst to remain relevant:[4]

Frank Sinatra stopped his car. The light was red. Pedestrians passed quickly across his windshield but, as usual, one did not. It was a girl in her twenties. She remained at the curb staring at him. Through the corner of his left eye he could see her, and he knew, because it happens almost every day, that she was thinking, It looks like him, but is it? Just before the light turned green, Sinatra turned toward her, looked directly into her eyes waiting for the reaction he knew would come. It came and he smiled. She smiled and he was gone.[1]

Influence on New Journalism

editThe article was an instant sensation. The journalist Michael Kinsley has said, "It's hard to imagine a magazine article today having the kind of impact that [this] article and others had in those days in terms of everyone talking about it purely on the basis of the writing and the style."[6]

After Tom Wolfe popularized the term "New Journalism" in his 1973 anthology The New Journalism, Talese's piece became widely studied and imitated.[7]

The piece is often contrasted to modern magazine profiles in which the writers spend little time with their subjects or when writers fabricate elements of their story, such as Jayson Blair, Stephen Glass, or Janet Cooke.[3][5][6]

Talese has come to reject the label of "New Journalism" for this reason. He told NPR: "The term new journalism became very fashionable on college campuses in the 1970s and some of its practitioners tended to be a little loose with the facts. And that's where I wanted to part company. I came up with The New York Times as a copy boy and later on became a reporter and I so revered the traditions of the Times in being accurate."[6]

The story continues to receive acclaim and is cited by Talese as one of his best works.[10][11] The story, which continues to be widely read, has been republished in multiple anthologies.[10][12]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f "Without question, picking The Best Story Esquire Ever Published is a fool's errand..." Esquire. 2003-10-01. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "The Master's Voice". The Economist. 2005-07-16.

- ^ a b c d "King of the day-glo, stiff-spined, wise-guy shiny sheets; In the world of glossy magazines, Esquire was to the 1960s what Vanity Fair was to the 1980s — the wittiest chronicler of its time". The Independent. 1997-02-08. Archived from the original on 2007-11-25. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Frank DiGiacomo (January 2007). "The Esquire Decade". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ a b Peter Carlson (2001-05-22). "Esquire's Celebrity Dish: Artificial Flavoring". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e f "Writer's Story on Sinatra Sparked a New Genre of Reporting". Day to Day on National Public Radio. 2003-09-09. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ a b c d e "Lecture: Gay Talese". NYU Bullpen. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Charles McGrath (2006-04-23). "Notes From Underground". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Stein, Sadie (2021-11-24). "The 'Profusely Illustrated' Life of Edward Sorel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ a b Gay Talese (2004). Retha Powers and Kathy Kiernan (ed.). This Is My Best; Great Writers Share Their Favorite Work. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. pp. 480–516. ISBN 0-8118-4829-9.

- ^ "So What Do You Do, Gay Talese?". mediabistro.com. 2004-04-27. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "Greatest! stories! ever! sort of: Esquire celebrates its best in a new book 70 years in the making". Ottawa Citizen. 2004-01-11.

External links

edit- Frank Sinatra Has a Cold in Esquire.

- Frank Sinatra Has a Cold with original images, cached by Google.