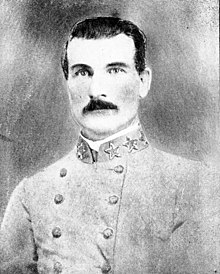

Francis Marion Walker (November 12, 1827 – July 22, 1864) was a Confederate States Army officer during the American Civil War (Civil War). He was killed while commanding a brigade at the Battle of Atlanta of July 22, 1864, one day before his commission as a brigadier general in the Confederate Army was delivered.

Francis Marion Walker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 12, 1827 Paris, Kentucky |

| Died | July 22, 1864 (aged 36) Atlanta, Georgia |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1847–1848 (USA) 1861–1864 (CSA) |

| Rank | Brigadier General (unconfirmed) |

| Unit | 5th Tennessee Infantry (USA) |

| Commands | 19th Tennessee Infantry F.M. Walker's Brigade |

| Battles / wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

Early life

editFrancis Marion Walker was born in Paris, Kentucky, on November 12, 1827, and was named in honor of Francis Marion.[1][2][3] His parents were John and Tabitha (Taylor) Walker.[1][4] Walker's mother died while he was young.[1] In 1843, the Walker family moved to Hawkins County in east Tennessee, where his father was proprietor of a tavern.[1][5] Walker had a limited formal education but taught school for his own education and to earn money for college tuition.[1]

Walker was elected second lieutenant in the 5th Tennessee Infantry Regiment, commanded by his father as colonel, during the Mexican–American War.[1][6] The unit was sent to Mexico but the war was over before it could be sent into action.[1]

Walker graduated with honors from Transylvania University in 1850.[1] He established a law practice in Rogersville, Tennessee.[1] In 1854, he moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee and set up a law practice.[1] He was a Chattanooga alderman in 1858–1859 and attorney general of the Tennessee Fourth District from 1860 until the start of the Civil War.[1]

Walker had a prominent son, Lapsley Greene Walker, a Chattanooga newspaperman who opposed the Ku Klux Klan.[7][8]

American Civil War service

editWalker was actually a committed Unionist and made speeches in support of the Union in eastern Tennessee before Tennessee declared its secession from the Union.[1] After Tennessee joined the Confederacy, Walker decided to stay with his State and joined the Confederate cause.[1] He became Captain of the "Marsh Blues" of Hamilton County, Tennessee, which became Company I of the 19th Tennessee Infantry Regiment.[1][2] The company was named for Ed Marsh, a local man who provided uniforms and equipment.[9] Walker was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the regiment on June 11, 1861.[1][2]

Walker's regiment fought at the Battle of Mill Springs and Battle of Shiloh, where both the unit and Walker were praised for bravery.[1] Walker received Union general Benjamin Prentiss' sword in surrender at Shiloh. Walker was elected Colonel of the 19th Tennessee Infantry on May 8, 1862.[1][2] Thereafter, he led the regiment at the Battle of Stone's River, Battle of Chickamauga and in the Chattanooga Campaign.[1] The regiment fought during the Atlanta campaign. Fighting from trenches, they decimated the soldiers of a Union assault at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain on June 27, 1864.[1]

Brigade commander, Brigadier Otho F. Strahl and corps commander, Lieutenant General William J. Hardee repeatedly recommended that Walker be promoted to brigadier general.[1] In June 1864, Walker was given command of a brigade in Major General Benjamin F. Cheatham's division when Brigadier General George Maney was promoted to division command.[1][2]

On July 17, 1864, just before the Battle of Peachtree Creek on July 20, 1864, Confederate President Jefferson Davis replaced General Joseph E. Johnston as commander of the Army of Tennessee defending Atlanta with the aggressive Lieutenant General, temporary General, John Bell Hood.[10][11][12] On July 22, 1864, Hood ordered Lieutenant General Hardee to maneuver around the left flank of the Union Army east of Atlanta for a surprise attack while Major General Cheatham, then in command of Hood's former corps, was to make a diversionary attack on the front of the Union force and the cavalry commander, Major General Joseph Wheeler, would attack their supply line.[13][14][15] The Battle of Atlanta, fought east and south of the city and near the Union supply lines further east at Decatur, Georgia, ensued.[13][14] During a hard day of fighting after a night march to get into position, Hardee's men succeeded in bending back the Union left flank and retaking some breastworks that had been built by the Confederates earlier.[16] Union Major General James B. McPherson, who was killed during the battle, anticipated the Confederate maneuver against the far end of his flank, reshaped his line and sent reinforcements to the flank.[13][17]

By 5:00 p.m., Confederate advances along the Union front had been reversed although the Union force had lost a large part of the left, or southern, part of their line.[18] Still part of the XVII Corps under Major General Francis Preston Blair Jr. still held a position anchored on Bald Hill.[19] Confederate Major General Patrick Cleburne, operating under Hardee, gathered available forces in the area to make a large assault against the Union position on Bald Hill.[20] Blair meanwhile had thought the Confederate effort had been spent and even suggested in a message to Union Army commander Major General William T. Sherman that with another brigade he could retake the lost ground.[20]

Francis M. Walker's men, which included his 19th Tennessee Infantry as well as Maney's old brigade, had not been engaged that day since they had been marched and countermarched almost back to their original position.[21] Cleburne placed Walker's brigade on the left front of the attacking force.[21] The attack was launched with about 3,500 men in total, with 2,000 more in a second wave, at about 6:00 p.m.[22] Cleburne himself led the attack with Walker's brigade.[22] The Union force had about half the number of men but they were behind their defenses.[22] Emerging from a stand of woods, Walker's men were hard hit and began to retreat before Cleburne and Maney rallied them.[23] Then they moved with a two-sided assault with troops to their right toward the Union line.[24] Despite taking about 100 casualties in their previous advances, Walker's men followed Walker, who was waving his sword in encouragement, toward the crest of the hill.[25] As they reached the crest, Walker's brigade was hit with a tremendous volley from defenders over the crest.[25] Walker was killed by that volley.[1][2][25] He had been appointed a brigadier general the previous day but he had not yet received written notification of his appointment.[1][2][25] Walker's commission arrived at his headquarters the day after he was killed.[25][26] After Walker's death, many of his men diverted to another point of attack to try to take a Union battery and suffered severe casualties.[27] As night fell, the Confederates could not continue the attack and the Union troops held their fort at the top of the hill.[28] The Confederates had sustained over 600 casualties while the Union defenders had endured about 550 casualties in the Battle of Bald Hill, which was but a small part of the overall Battle of Atlanta.[29][30]

Although Walker could have acted as a brigadier general from the receipt of the commission, he still would not have officially and legally been a brigadier general until after his appointment had been confirmed by the Confederate Senate.[31] The Confederate Senate had not confirmed the appointment as of the date of Walker's death.[2]

Aftermath

editWalker initially was buried in Citizens Cemetery at Griffin, Georgia.[32] His remains were reinterred in a family plot in Forest Hills Cemetery in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1889.[2][32]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Allardice, Bruce S. More Generals in Gray. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8071-3148-2 (pbk.). p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. p. 614.

- ^ Allardice, 1995, p. 232 says that census records refute an alternate date of birth in 1821 that has sometimes been given for Walker.

- ^ Allardice, 1995, p. 232 says that he investigated the claim by sources such as Armstrong, 1931, pp. 466–467 which state that Walker's mother was a niece of President Zachary Taylor and could find no support for the claim.

- ^ In 1857, John Walker was appointed Indian agent to the Tohono O'odham (previously sometimes referred to as the Papago people), Pima people and Maricopa people at Tucson, Arizona. Thrapp, Dan L. 'Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: P-Z'. Volume 3. Glendale, CA: A. H. Clark Co., 1988. ISBN 978-0-8032-9420-2. p. 1498.

- ^ Thrapp, Dan L. 'Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: P-Z'. Volume 3. Glendale, CA: A. H. Clark Co., 1988. ISBN 978-0-8032-9420-2. p. 1498.

- ^ Moore, Gay Morgan. 'Chattanooga's Forest Hills Cemetery' Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7385-8694-6. p. 54.

- ^ A genealogical book states that Mary Ann (Baily) Walker, widow of Francis Marion Walker, married John Perry L. May, born 1839, but does not give a date. The time period appears to be correct for this widow to have been the wife of Colonel Walker. Doliante Sharon J. 'Maryland and Virginia Colonials: Genealogies of Some Colonial Families'. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1991. ISBN 978-0-8063-4762-2. p. 99. On the other hand, another source says that Walker's wife was Mary (Kelso) Walker and that they had five children. Hale, Will Thomas and Dixon Lanier Merrit. 'A history of Tennessee and Tennesseans: the leaders and representative men in commerce, industry and modern activities', Volume 7. Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1913. OCLC 1600429. p. 2100. In Allardice, Bruce S. Confederate Colonels: A Biographical Register. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8262-1809-4., Allardice agrees that her name was Margaret Kelso.

- ^ Armstrong, Zella. 'The History of Hamilton County and Chattanooga, Tennessee', Volume 2. Chattanooga, TN: Lookout Publishing Company, 1940. Reprint: The Overmountain Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-932807-99-1. p. 291.

- ^ Kagan, Neil, and Stephen G. Hyslop. Eyewitness to the Civil War: The Complete History From Secession to Reconstruction. Washington D.C.: National Geographic, 2006. ISBN 978-07922-5280-1. p. 323.

- ^ McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0. p. 753.

- ^ Ecelbarger, Gary L. The Day Dixie Died: The Battle of Atlanta. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0-312-56399-8. p. 21.

- ^ a b c Kagan, 2006, p. 324.

- ^ a b McPherson, 1988, p. 754.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, pp. 147, 170.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, pp. 189–191,

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 191.

- ^ a b Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 193.

- ^ a b Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 195.

- ^ a b c Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 196.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d e Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 201.

- ^ Allardice, 1995, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 204.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 205.

- ^ Ecelbarger, 2010, p. 206.

- ^ Allardice, 1995, p. 231 gives the date of Walker's death as June 22, 1864. This is clearly wrong as the Battle of Atlanta was fought on July 22, 1864 as Eicher and other sources show. Eicher, 2001, p. 614 gives the correct date of Walker's death, July 22, 1864.

- ^ Eicher, 2001, 30–32, 66–67.

- ^ a b Allardice, 1995, p. 232.

Bibliography

edit- Allardice, Bruce S. Confederate Colonels: A Biographical Register. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8262-1809-4.

- Allardice, Bruce S. More Generals in Gray. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8071-1967-9.

- Armstrong, Zella. 'The History of Hamilton County and Chattanooga, Tennessee', Volume 2. Chattanooga, TN: Lookout Publishing Company, 1940. Reprint: The Overmountain Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-932807-99-1.

- Doliante Sharon J. 'Maryland and Virginia Colonials: Genealogies of Some Colonial Families'. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1991. ISBN 978-0-8063-4762-2.

- Ecelbarger, Gary L. The Day Dixie Died: The Battle of Atlanta. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0-312-56399-8.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Hale, Will Thomas and Dixon Lanier Merrit. 'A history of Tennessee and Tennesseans: the leaders and representative men in commerce, industry and modern activities', Volume 7. Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1913. OCLC 1600429.

- Kagan, Neil, and Stephen G. Hyslop. Eyewitness to the Civil War: The Complete History From Secession to Reconstruction. Washington D.C.: National Geographic, 2006. ISBN 978-07922-5280-1.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Moore, Gay Morgan. 'Chattanooga's Forest Hills Cemetery' Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7385-8694-6.

- Thrapp, Dan L. 'Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: P-Z'. Volume 3. Glendale, CA: A. H. Clark Co., 1988. ISBN 978-0-8032-9420-2. p. 1498.