Fort Worth is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the seat of Tarrant County, covering nearly 350 square miles (910 km2) into Denton, Johnson, Parker, and Wise counties. According to the 2024 United States census estimate, Fort Worth's population was 996,756 making it the fifth-most populous city in the state and the 12th-most populous in the United States.[8][9] Fort Worth is the second-largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, which is the fourth-most populous metropolitan area in the United States and the most populous in Texas.[10][11]

Fort Worth | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto(s): "Where the West begins";[2] "Crossroads of Cowboys & Culture" | |

Interactive map of Fort Worth | |

| Coordinates: 32°45′23″N 97°19′57″W / 32.75639°N 97.33250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Counties | Tarrant, Denton, Johnson, Parker, Wise [1] |

| Incorporated | 1874[4] |

| Named for | William J. Worth |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council–manager |

| • Mayor | Mattie Parker (R) |

| • City manager | David Cooke (R) |

| • City council | List |

| Area | |

| • City | 355.56 sq mi (920.89 km2) |

| • Land | 347.27 sq mi (899.44 km2) |

| • Water | 8.28 sq mi (21.45 km2) |

| Elevation | 541 ft (165 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 918,915 |

| • Estimate (2024)[7] | 996,756 |

| • Rank | 33rd in North America 12th in the United States 5th in Texas |

| • Density | 2,600/sq mi (1,000/km2) |

| • Metro | 7,637,387 |

| Demonym | Fort Worthian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 76008, 76036, 761XX, 76244 |

| Area codes | 682 and 817 |

| FIPS code | 48-27000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2410531[6] |

| Website | www.fortworthtexas.gov |

The city of Fort Worth was established in 1849 as an army outpost on a bluff overlooking the Trinity River.[12] Fort Worth has historically been a center of the Texas Longhorn cattle trade.[12] It still embraces its Western heritage and traditional architecture and design.[13][14] USS Fort Worth (LCS-3) is the first ship of the United States Navy named after the city.[15] Nearby Dallas has held a population majority as long as records have been kept, yet Fort Worth has become one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States at the beginning of the 21st century, nearly doubling its population since 2000.

Fort Worth is the location of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition and several museums designed by contemporary architects. The Kimbell Art Museum was designed by Louis Kahn, with an additional designs by Renzo Piano.[16] The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth was designed by Tadao Ando. The Amon Carter Museum of American Art, designed by Philip Johnson, houses American art. The Sid Richardson Museum, redesigned by David M. Schwarz, has a collection of Western art in the United States emphasizing Frederic Remington and Charles Russell. The Fort Worth Museum of Science and History was designed by Ricardo Legorreta of Mexico.

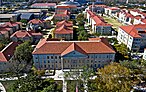

In addition, the city of Fort Worth is the location of several universities including, Texas Christian University, Texas Wesleyan, University of North Texas Health Science Center, and Texas A&M University School of Law. Several multinational corporations, including Bell Textron, American Airlines, and BNSF Railway, are headquartered in Fort Worth.

History

editThe Treaty of Bird's Fort between the Republic of Texas and several Native American tribes was signed in 1843 at Bird's Fort in present-day Arlington, Texas.[17][18] Article XI of the treaty provided that no one may "pass the line of trading houses" (at the border of the Indians' territory) without permission of the President of Texas, and may not reside or remain in the Indians' territory. These "trading houses" were later established at the junction of the Clear Fork and West Fork of the Trinity River in present-day Fort Worth.[19]

A line of seven army posts was established in 1848–1849 after the Mexican War to protect the settlers of Texas along the western American Frontier and included Fort Worth, Fort Graham, Fort Gates, Fort Croghan, Fort Martin Scott, Fort Lincoln, and Fort Duncan.[20] Originally, 10 forts had been proposed by Major General William Jenkins Worth (1794–1849), who commanded the Department of Texas in 1849. In January 1849, Worth proposed a line of 10 forts to mark the western Texas frontier from Eagle Pass to the confluence of the West Fork and Clear Fork of the Trinity River. One month later, Worth died from cholera in South Texas.[20]

General William S. Harney assumed command of the Department of Texas and ordered Major Ripley A. Arnold (Company F, Second United States Dragoons)[20] to find a new fort site near the West Fork and Clear Fork. On June 6, 1849, Arnold, advised by Middleton Tate Johnson, established a camp on the bank of the Trinity River and named the post Camp Worth in honor of the late General Worth. In August 1849, Arnold moved the camp to the north-facing bluff, which overlooked the mouth of the Clear Fork of the Trinity River. The United States War Department officially named the post Fort Worth on November 14, 1849.[21] Since its establishment, the city of Fort Worth continues to be known as "where the West begins".[12]

E. S. Terrell (1812–1905) from Tennessee claimed to be the first resident of Fort Worth.[22] The fort was flooded the first year and moved to the top of the bluff; the current courthouse was built on this site. The fort was abandoned September 17, 1853.[20] No trace of it remains.

As a stop on the legendary Chisholm Trail, Fort Worth was stimulated by the business of the cattle drives and became a brawling, bustling town. Millions of head of cattle were driven north to market along this trail. Fort Worth became the center of the cattle drives, and later, the ranching industry. It was given the nickname of Cowtown.[23]

During the American Civil War, Fort Worth suffered from shortages of money, food, and supplies. The population dropped as low as 175, but began to recover during Reconstruction. By 1872, Jacob Samuels, William Jesse Boaz, and William Henry Davis had opened general stores. The next year, Khleber M. Van Zandt established Tidball, Van Zandt, and Company, which became Fort Worth National Bank in 1884.

In 1875, the Dallas Herald published an article by a former Fort Worth lawyer, Robert E. Cowart, who wrote that the decimation of Fort Worth's population, caused by the economic disaster and hard winter of 1873, had dealt a severe blow to the cattle industry. Added to the slowdown due to the railroad's stopping the laying of track 30 miles (48 km) outside of Fort Worth, Cowart said that Fort Worth was so slow that he saw a panther asleep in the street by the courthouse. Although an intended insult, the name Panther City was enthusiastically embraced when in 1876 Fort Worth recovered economically.[24] Many businesses and organizations continue to use Panther in their name. A panther is set at the top of the police department badges.[25]

The "Panther City" tradition is also preserved in the names and design of some of the city's geographical/architectural features, such as Panther Island (in the Trinity River), the Flat Iron Building, Fort Worth Central Station, and in two or three "Sleeping Panther" statues.

In 1876, the Texas and Pacific Railway finally was completed to Fort Worth, stimulating a boom and transforming the Fort Worth Stockyards into a premier center for the cattle wholesale trade.[26] Migrants from the devastated war-torn South continued to swell the population, and small, community factories and mills yielded to larger businesses. Newly dubbed the "Queen City of the Prairies",[27] Fort Worth supplied a regional market via the growing transportation network.

Fort Worth became the westernmost railhead and a transit point for cattle shipment. Louville Niles, a Boston, Massachusetts-based businessman and main shareholder of the Fort Worth Stockyards Company, is credited with bringing the two biggest meatpacking firms at the time, Armour and Swift, to the stockyards.[28]

With the boom times came a variety of entertainments and related problems. Fort Worth had a knack for separating cattlemen from their money. Cowboys took full advantage of their last brush with civilization before the long drive on the Chisholm Trail from Fort Worth north to Kansas. They stocked up on provisions from local merchants, visited saloons for a bit of gambling and carousing, then rode northward with their cattle, only to whoop it up again on their way back. The town soon became home to "Hell's Half-Acre", the biggest collection of saloons, dance halls, and bawdy houses south of Dodge City (the northern terminus of the Chisholm Trail), giving Fort Worth the nickname of the "Paris of the Plains".[29][30]

Certain sections of town were off-limits for proper citizens. Shootings, knifings, muggings, and brawls became a nightly occurrence. Cowboys were joined by a motley assortment of buffalo hunters, gunmen, adventurers, and crooks. Hell's Half Acre (also known as simply "The Acre") expanded as more people were drawn to the town. Occasionally, the Acre was referred to as "the bloody Third Ward" after it was designated one of the city's three political wards in 1876. By 1900, the Acre covered four of the city's main north-south thoroughfares.[31] Local citizens became alarmed about the activities, electing Timothy Isaiah "Longhair Jim" Courtright in 1876 as city marshal with a mandate to tame it.

Courtright sometimes collected and jailed 30 people on a Saturday night, but allowed the gamblers to operate, as they attracted money to the city. After learning that train and stagecoach robbers, such as the Sam Bass gang, were using the area as a hideout, he intensified law enforcement, but certain businessmen advertised against too many restrictions in the area as having bad effects on the legitimate businesses. Gradually, the cowboys began to avoid the area; as businesses suffered, the city moderated its opposition. Courtright lost his office in 1879.[31]

Despite crusading mayors such as H.S. Broiles and newspaper editors such as B. B. Paddock, the Acre survived because it generated income for the city (all of it illegal) and excitement for visitors. Longtime Fort Worth residents claimed the place was never as wild as its reputation, but during the 1880s, Fort Worth was a regular stop on the "gambler's circuit" by Bat Masterson, Doc Holliday, and the Earp brothers (Wyatt, Morgan, and Virgil).[31] James Earp, the eldest of his brothers, lived with his wife in Fort Worth during this period; their house was at the edge of Hell's Half Acre, at 9th and Calhoun. He often tended bar at the Cattlemen's Exchange saloon in the "uptown" part of the city.[32]

Reforming citizens objected to the dance halls, where men and women mingled; by contrast, the saloons or gambling parlors had primarily male customers.

In the late 1880s, Mayor Broiles and County Attorney R. L. Carlock initiated a reform campaign. In a public shootout on February 8, 1887, Jim Courtright was killed on Main Street by Luke Short, who claimed he was "King of Fort Worth Gamblers".[31] As Courtright had been popular, when Short was jailed for his murder, rumors floated of lynching him. Short's good friend Bat Masterson came armed and spent the night in his cell to protect him.

The first prohibition campaign in Texas was mounted in Fort Worth in 1889, allowing other business and residential development in the area. Another change was the influx of Black and African American residents. Excluded by state segregation from the business end of town and the more costly residential areas, the city's black citizens settled into the southern portion of the city. The popularity and profitability of the Acre declined and more derelicts and the homeless were seen on the streets. By 1900, most of the dance halls and gamblers were gone. Cheap variety shows and prostitution became the chief forms of entertainment. Some progressive politicians launched an offensive to seek out and abolish these perceived "vices" as part of the broader Progressive Era package of reforms.[31]

In 1911, the Reverend J. Frank Norris launched an offensive against racetrack gambling in the Baptist Standard and used the pulpit of the First Baptist Church of Fort Worth to attack vice and prostitution. When he began to link certain Fort Worth businessmen with property in the Acre and announced their names from his pulpit, the battle heated up. On February 4, 1912, Norris's church was burned to the ground; that evening, his enemies tossed a bundle of burning oiled rags onto his porch, but the fire was extinguished and caused minimal damage. A month later, the arsonists succeeded in burning down the parsonage. In a sensational trial lasting a month, Norris was charged with perjury and arson in connection with the two fires. He was acquitted, but his continued attacks on the Acre accomplished little until 1917. A new city administration and the federal government, which was eyeing Fort Worth as a potential site for a major military training camp, joined forces with the Baptist preacher to bring down the final curtain on the Acre.

The police department compiled statistics showing that 50% of the violent crime in Fort Worth occurred in the Acre, which confirmed respectable citizens' opinion of the area. After Camp Bowie (a World War I U.S. Army training installation) was located on the outskirts of Fort Worth in 1917, the military used martial law to regulate prostitutes and barkeepers of the Acre. Fines and stiff jail sentences curtailed their activities. By the time Norris held a mock funeral parade to "bury John Barleycorn" in 1919, the Acre had become a part of Fort Worth history. The name continues to be associated with the southern end of Fort Worth.[33]

In 1921, the whites-only union workers in the Fort Worth, Swift & Co. meatpacking plant in the Niles City Stockyards went on strike. The owners attempted to replace them with black strikebreakers. During union protests, strikebreaker African-American Fred Rouse was lynched on a tree at the corner of NE 12th Street and Samuels Avenue. After he was hanged a white mob riddled his mutilated body with gunshots.[34]

On November 21, 1963, President John F. Kennedy arrived in Fort Worth, speaking the next morning before a breakfast meeting of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, then proceeding to Dallas where he was assassinated later that day.

When oil began to gush in West Texas in the early 20th century, and again in the late 1970s, Fort Worth was at the center of the boom. By July 2007, advances in horizontal drilling technology made vast natural gas reserves in the Barnett Shale available directly under the city,[35] helping many residents receive royalty checks for their mineral rights. Today, the City of Fort Worth and many residents are dealing with the benefits and issues associated with the natural-gas reserves underground.[36][37]

On March 28, 2000, at 6:15 pm, an F3 tornado struck downtown Fort Worth, severely damaging many buildings. One of the hardest-hit structures was the Bank One Tower, which was one of the dominant features of the Fort Worth skyline and which had "Reata," a popular restaurant, on its top floor. It has since been converted to upscale condominiums and officially renamed "The Tower." This was the first major tornado to strike Fort Worth proper since the early 1940s.[38]

From 2000 to 2006, Fort Worth was the fastest-growing large city in the United States;[39] it was voted one of "America's Most Livable Communities".[40] In addition to the reversal migration, many African Americans have been relocating to Fort Worth for its affordable cost of living and job opportunities.[41]

In 2020, Fort Worth's mayor announced the city's continued growth to 20.78%.[42] The U.S. Census Bureau also noted the city's beginning of greater diversification from 2014–2018.[43]

On February 11, 2021, a pileup involving 133 cars and trucks crashed on I-35W due to freezing rain leaving ice. The pileup left at least six people dead and multiple injured.[44][45][46]

Geography

editFort Worth is located in North Texas, and has a generally humid subtropical climate.[47] It is part of the Cross Timbers region;[48] this region is a boundary between the more heavily forested eastern parts and the rolling hills and prairies of the central part. Specifically, the city is part of the Grand Prairie ecoregion within the Cross Timbers. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 349.2 square miles (904 km2), of which 342.2 square miles (886 km2) are land and 7.0 square miles (18 km2) are covered by water. It is a principal city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, and the second largest by population.

The city of Fort Worth is not entirely contiguous and has several enclaves, practical enclaves, semi-enclaves, and cities that are otherwise completely or nearly surrounded by it, including: Westworth Village, River Oaks, Saginaw, Blue Mound, Benbrook, Everman, Forest Hill, Edgecliff Village, Westover Hills, White Settlement, Sansom Park, Lake Worth, Lakeside, and Haslet.

Fort Worth contains over 1,000 natural-gas wells (December 2009 count) tapping the Barnett Shale.[49] Each well site is a bare patch of gravel 2–5 acres (8,100–20,200 m2) in size. As city ordinances permit them in all zoning categories, including residential, well sites can be found in a variety of locations. Some wells are surrounded by masonry fences, but most are secured by chain link.

A large storage dam was completed in 1914 on the West Fork of the Trinity River, 7 miles (11 km) from the city, with a storage capacity of 33,495 acre feet of water.[50] The lake formed by this dam is known as Lake Worth.

Neighborhoods

editDowntown

editDowntown Fort Worth consists of numerous districts comprising commercial and retail, residential, and entertainment. Among them, Sundance Square is a mixed-use district and popular for nightlife and entertainment. The Bass Performance Hall is located within Sundance Square. Nearby Upper West Side is also a notable district within downtown Fort Worth. It is bound roughly by Henderson Street to the east, the Trinity River to the west, Interstate 30 to the south, and White Settlement Road to the north. The neighborhood contains several small and mid-sized office buildings and urban residences, but very little retail.

Stockyards

editThe Fort Worth Stockyards are a National Historic District.[51] The Stockyards was once among the largest livestock markets in the United States and played a vital role in the city's early growth.[52] Today the neighborhood is characterized by its many bars, restaurants, and notable country music venues such as Billy Bob's. Fort Worth celebrity chef Tim Love of Iron Chef America and Top Chef Masters has operated multiple restaurants in the neighborhood.[53][54] There is a mall at the Stockyards Station and a train via Grapevine Vintage Railroad, that connects to downtown Grapevine.[55] Cowtown Coliseum hosts a weekly rodeo and also has the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame.[56][57] The world's largest honky tonk is also in the Stockyards at Billy Bob's.[58] At the Fort Worth Stockyards, Fort Worth is the only major city that hosts a daily cattle drive.[59]

Tanglewood

editTanglewood consists of land in the low areas along the branch of the Trinity River and is approximately five miles southwest from the Fort Worth central business district.[60][61] The Tanglewood area lies within two surveys. The western part of the addition is part of the 1854 Felix G. Beasley survey, and the eastern part, along the branch of the river, is the 1876 James Howard survey. The original approach to the Tanglewood area consisted of a two-rut dirt road, which is now Bellaire Drive South. Up to the time of development, children enjoyed swimming in the river in a deep hole that was located where the bridge is now on Bellaire Drive South near Trinity Commons Shopping Center. The portions of Tanglewood that are now Bellaire Park Court, Marquette Court, and Autumn Court were originally a dairy farm.

Architecture

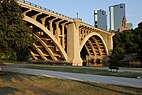

editDowntown Fort Worth, with its unique rustic architecture, is mainly known for its Art Deco-style buildings. The Tarrant County Courthouse was created in the American Beaux Arts design, which was modeled after the Texas State Capitol building. Most of the structures around downtown's Sundance Square have preserved their early 20th-century façades. Multiple blocks surrounding Sundance Square are illuminated at night in Christmas lights year-round.

Climate

editFort Worth has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) according to the Köppen climate classification system, and is within USDA hardiness zone 8a.[62] This region features very hot, humid summers and mild to cool winters. The hottest month of the year is August, when the average high temperature is 96 °F (35.6 °C), and overnight low temperatures average 75 °F (23.9 °C), giving an average temperature of 85 °F (29.4 °C).[63] The coldest month of the year is January, when the average high temperature is 56 °F (13.3 °C) and low temperatures average 35 °F (1.7 °C).[63] The average temperature in January is 46 °F (8 °C).[63] The highest temperature ever recorded in Fort Worth is 113 °F (45.0 °C), on June 26, 1980, during the Great 1980 Heat Wave, and June 27, 1980.[64] The coldest temperature ever recorded in Fort Worth was −8 °F (−22.2 °C) on February 12, 1899. Because of its position in North Texas, Fort Worth is very susceptible to supercell thunderstorms, which produce large hail and can produce tornadoes.

The average annual precipitation for Fort Worth is 34.01 inches (863.9 mm).[63] The wettest month of the year is May, when an average of 4.58 inches (116.3 mm) of precipitation falls.[63] The driest month of the year is January, when only 1.70 inches (43.2 mm) of precipitation falls.[63] The driest calendar year since records began has been 1921 with 17.91 inches (454.9 mm) and the wettest 2015 with 62.61 inches (1,590.3 mm). The wettest calendar month has been April 1922 with 17.64 inches (448.1 mm), including 8.56 inches (217.4 mm) on April 25.

The average annual snowfall in Fort Worth is 2.6 inches (66.0 mm).[65] The most snowfall in one month has been 13.5 inches (342.9 mm) in February 1978, and the most in a season 17.6 inches (447.0 mm) in 1977/1978.

The National Weather Service office, which serves the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, is based in northeastern Fort Worth.[66]

| Climate data for Fort Worth Meacham International Airport, Texas (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1940–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

97 (36) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

107 (42) |

112 (44) |

110 (43) |

112 (44) |

106 (41) |

95 (35) |

90 (32) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.1 (25.6) |

81.1 (27.3) |

86.0 (30.0) |

89.5 (31.9) |

95.5 (35.3) |

99.6 (37.6) |

103.6 (39.8) |

104.3 (40.2) |

99.3 (37.4) |

92.7 (33.7) |

83.2 (28.4) |

78.1 (25.6) |

105.7 (40.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 56.4 (13.6) |

60.5 (15.8) |

68.0 (20.0) |

75.6 (24.2) |

83.5 (28.6) |

91.5 (33.1) |

95.7 (35.4) |

95.9 (35.5) |

88.3 (31.3) |

77.9 (25.5) |

66.2 (19.0) |

57.8 (14.3) |

76.4 (24.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 45.8 (7.7) |

49.8 (9.9) |

57.3 (14.1) |

64.7 (18.2) |

73.3 (22.9) |

81.4 (27.4) |

85.1 (29.5) |

85.2 (29.6) |

77.7 (25.4) |

66.9 (19.4) |

55.7 (13.2) |

47.5 (8.6) |

65.9 (18.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.3 (1.8) |

39.1 (3.9) |

46.5 (8.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

71.2 (21.8) |

74.6 (23.7) |

74.5 (23.6) |

67.1 (19.5) |

55.9 (13.3) |

45.3 (7.4) |

37.3 (2.9) |

55.3 (12.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19.9 (−6.7) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

37.6 (3.1) |

49.1 (9.5) |

62.0 (16.7) |

68.8 (20.4) |

66.8 (19.3) |

53.9 (12.2) |

39.7 (4.3) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

16.5 (−8.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

−2 (−19) |

10 (−12) |

28 (−2) |

38 (3) |

52 (11) |

60 (16) |

58 (14) |

40 (4) |

24 (−4) |

19 (−7) |

10 (−12) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.05 (52) |

2.41 (61) |

3.16 (80) |

3.06 (78) |

4.02 (102) |

4.02 (102) |

2.18 (55) |

2.23 (57) |

2.59 (66) |

4.46 (113) |

2.52 (64) |

2.64 (67) |

35.34 (898) |

| Average precipitation days | 7.2 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 79.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 186.0 | 169.5 | 217.0 | 240.0 | 248.0 | 300.0 | 341.0 | 310.0 | 240.0 | 217.0 | 180.0 | 186.0 | 2,834.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 60 | 55 | 58 | 62 | 57 | 71 | 79 | 77 | 67 | 64 | 60 | 60 | 64 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Source 1: National Climatic Data Center[67] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas [68] (sunshine data, UV index) | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 6,663 | — | |

| 1890 | 23,076 | 246.3% | |

| 1900 | 26,668 | 15.6% | |

| 1910 | 73,312 | 174.9% | |

| 1920 | 106,482 | 45.2% | |

| 1930 | 163,447 | 53.5% | |

| 1940 | 177,662 | 8.7% | |

| 1950 | 278,778 | 56.9% | |

| 1960 | 356,268 | 27.8% | |

| 1970 | 393,476 | 10.4% | |

| 1980 | 385,164 | −2.1% | |

| 1990 | 447,619 | 16.2% | |

| 2000 | 534,697 | 19.5% | |

| 2010 | 741,206 | 38.6% | |

| 2020 | 918,915 | 24.0% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 978,468 | [69] | 6.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[70] 2010–2020[7] | |||

Fort Worth is the most populous city in Tarrant County, and second-most populous community within the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex. Its metropolitan statistical area encompasses one-quarter of the population of Texas, and is the largest in the Southern U.S. and Texas followed by the Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land metropolitan area. At the American Community Survey's 2018 census estimates, the city of Fort Worth had a population near 900,000 residents.[43] In 2019, it grew to an estimated 909,585. At the 2020 United States census, Fort Worth had a population of 918,915 and 2022 census estimates numbered approximately 956,709 residents.[8]

There were 337,072 housing units, 308,188 households, and 208,389 families at the 2018 census estimates.[71] The average household size was 2.87 persons per household, and the average family size was 3.50. Fort Worth had an owner-occupied housing rate of 56.4% and renter-occupied housing rate of 43.6%. The median income in 2018 was $58,448 and the mean income was $81,165.[72] The city had a per capita income of $29,010.[73] Roughly 15.6% of Fort Worthers lived at or below the poverty line.[74]

In 2010's American Community Survey census estimates there were 291,676 housing units,[75] 261,042 households, and 174,909 families.[76] Fort Worth had an average household size of 2.78 and the average family size was 3.47. A total of 92,952 households had children under 18 years living with them. There were 5.9% opposite sex unmarried-partner households and 0.5% same sex unmarried-partner households in 2010. The owner-occupied housing rate of Fort Worth was 59.0% and the renter-occupied housing rate was 41.0%. Fort Worth's median household income was $48,224 and the mean was $63,065.[77] An estimated 21.4% of the population lived at or below the poverty line.[78]

Race and ethnicity

edit| Racial and ethnic composition | 2020[79] | 2010[80] | 1990[81] | 1970[81] | 1940[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 36.6% | 41.7% | 56.5% | 72.0%[a] | n/a |

| Hispanic or Latino | 34.8% | 34.1% | 19.5% | 7.9%[a] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 19.2% | 18.9% | 22.0% | 19.9% | 14.2% |

| Asian | 5.1% | 3.7% | 2.0% | 0.1% | - |

At the 2010 U.S. census, the racial composition of Fort Worth's population was 61.1% White (non-Hispanic whites: 41.7%), 18.9% Black or African American, 0.6% Native American, 3.7% Asian American, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 34.1% Hispanic or Latino (of any race), and 3.1% of two or more races. In 2018, 38.2% of Fort Worth was non-Hispanic white, 18.6% Black or African American, 0.4% American Indian or Alaska Native, 4.8% Asian American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.1% from two or more races, and 35.5% Hispanic or Latino (of any race), marking an era of diversification in the city limits.[43][82]

A study determined Fort Worth as one of the most diverse cities in the United States in 2019.[83] For contrast, in 1970, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Fort Worth's population as 72% non-Hispanic white, 19.9% African American, and 7.9% Hispanic or Latino.[81] By the 2020 census,[79] continued population growth spurred further diversification with 36.6% of the population being non-Hispanic white, 34.8% Hispanic or Latino American of any race, and 19.2% Black or African American; Asian Americans increased to forming 5.1% of the population, reflecting nationwide demographic trends at the time.[84][85][86] In 2020, a total of 31,485 residents were of two or more races.[79]

Religion

editLocated within the Bible Belt, Christianity is the largest collective religious group in Fort Worth proper, and the Metroplex. Both Dallas and Dallas County, and Fort Worth and Tarrant County have a plurality of Roman Catholic residents.[87][88] Overall, the Dallas metropolitan division of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex is more religiously diverse than Fort Worth and its surrounding suburbs, particularly in the principal cities' counties.

The oldest continuously operating church in Fort Worth is First Christian Church, founded in 1855.[89] Other historical churches continuing operation in the city include St. Patrick Cathedral (founded 1888), Saint James Second Street Baptist Church (founded 1895), Tabernacle Baptist Church (built 1923), St. Mary of the Assumption Church (built 1924), Our Mother of Mercy Catholic Church and Parsonage (built 1929 and 1911), and Morning Chapel C.M.E. Church (built 1934).

According to the Association of Religion Data Archives in 2020, Tarrant County's Catholic community numbered 359,705,[87] and was the Fort Worth metropolitan division's single largest Christian denomination or tradition with 378,490 adherents.[90] According to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth, there are approximately 1,200,000 Catholics altogether as of 2023.[91] Among other Christian bodies embodying catholicity, the Association of Religion Data Archives reported the Coptic Orthodox Church was the largest Eastern Christian group, followed by the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America and Orthodox Church in America, the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America, and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church numbering 6,216 altogether.

Home to a large Protestant Christian community, Southern Baptists were the second-largest single Christian denomination for Fort Worth's metropolitan division in 2020, with 347,771 adherents.[90] Southern Baptists have been divided between the more traditionalist and conservative Southern Baptists of Texas Convention, and the theologically moderate Baptist General Convention of Texas; according to the Baptist General Convention of Texas, there are 167 churches within the vicinity of Fort Worth proper as of 2023.[92] The Southern Baptists of Texas Convention listed 117 churches in 2023.[93] Other prominent Baptist denominations such as the National Missionary Baptist Convention, National Baptist Convention, National Baptist Convention of America, Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship, American Baptist Association, and the National Association of Free Will Baptists collectively numbered 51,261 at the 2020 study.

Non- and inter-denominational churches dominated Fort Worth's religious landscape as the third-largest group of Christians. Having more than 289,554 adherents,[90] non/inter-denominational Christians represented the growing trend of ecumenism within the United States.[94][95] Methodists were the fourth-largest Christian group with more than 100,000 adherents of the United Methodist Church spread throughout Fort Worth's metropolitan division. The African Methodist Episcopal Church, Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and Free Methodist Church also formed a substantial portion of the area's Methodist population. Pentecostals, descended from the Wesleyan-Holiness movement of Methodists, formed the fifth-largest Christian constituency and primarily divided between the Assemblies of God USA and Church of God in Christ.

Among Fort Worther's non-Christian community, Islam and Judaism were the second- and third-largest religious communities.[90] According to the Association of Religion Data Archives, there were an estimated 37,488 Muslims and 2,413 Jews living in Fort Worth's vicinity, although the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life estimated 5,000 Jews in 2010.[96] Religions including Hinduism and Baha'i had a minuscule presence in the Fort Worth area according to the 2020 study, and Christendom remained more prevalent than in the Dallas metropolitan division.[90]

Economy

editAt its inception, Fort Worth relied on cattle drives that traveled the Chisholm Trail. Millions of cattle were driven north to market along this trail, and Fort Worth became the center of cattle drives, and later, ranching until the American Civil War. During the American Civil War, Fort Worth suffered shortages causing its population to decline. It recovered during the Reconstruction with general stores, banks, and "Hell's Half-Acre", a large collection of saloons and dance halls which increased business and criminal activity in the city. By the early 20th century the military used martial law to regulate Hell's Half-Acre's bartenders and prostitutes.

Since the late 20th century several major companies have been headquartered in Fort Worth. These include American Airlines Group (and subsidiaries American Airlines and Envoy Air), the John Peter Smith Hospital, Pier 1 Imports, Chip 1 Exchange,[97] RadioShack, Pioneer Corporation, Cash America International, GM Financial,[98] Budget Host, the BNSF Railway, and Bell Textron. Companies with a significant presence in the city are Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Lockheed Martin, GE Transportation, and Dallas-based telecommunications company AT&T. Metro by T-Mobile is also prominent in the city.

Culture

editBuilding on its Frontier Western heritage and a history of strong local arts patronage, Fort Worth promotes itself as the "City of Cowboys and Culture".[99] Fort Worth has the world's first and largest indoor rodeo,[100] world-class museums, a calendar of festivals and a robust local arts scene. The Academy of Western Artists, based in Gene Autry, Oklahoma, presents its annual awards in Fort Worth in fields related to the American cowboy, including music, literature, and even chuck wagon cooking.[101] Fort Worth is also the 1931 birthplace of the Official State Music of Texas—Western Swing, which was created by Bob Wills and Milton Brown and their Light Crust Doughboys band in a ramshackle dancehall 4 miles west of downtown at the Crystal Springs Dance Pavilion.[102]

Arts and sciences

edit- Theatre

- Amphibian Stage Productions

- Bass Performance Hall

- Casa Mañana

- Circle Theatre

- Jubilee Theater

- Kids Who Care Inc.

- Stage West

- Music

- Billy Bob's

- Fort Worth Opera

- Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra

- Live Eclectic Music (Ridglea Theater)[103]

- Texas Ballet Theater

- Van Cliburn International Piano Competition

- Museums

- Al and Ann Stohlman Museum

- American Airline C.R. Smith Museum

- Amon Carter Museum of American Art

- Fort Worth Museum of Science and History

- Fort Worth Stockyards Museum

- Kimbell Art Museum

- Lenora Rolla Heritage Center Museum

- Log Cabin Village

- Military Museum of Fort Worth

- Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

- National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame

- National Multicultural Western Heritage Museum

- Sid Richardson Museum

- Texas Civil War Museum

- Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame

Nature

editThe Fort Worth Zoo is home to over 5,000 animals.

The Fort Worth Botanic Garden and the Botanical Research Institute of Texas are also in the city. For those interested in hiking, birding, or canoeing, the Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge in northwest Fort Worth is a 3,621-acre preserved natural area designated by the Department of the Interior as a National Natural Landmark Site in 1980. Established in 1964 as the Greer Island Nature Center and Refuge, it celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2014.[104] The Nature Center has a small, genetically pure bison herd, and native prairies, forests, and wetlands. It is one of the largest urban parks of its type in the United States.[105]

Parks

editFort Worth has a total of 263 parks with 179 of those being neighborhood parks. The total acres of parkland is 11,700.72 acres with the average being about 12.13 acres per park.[106]

The 4.3 acre (1.7 hectare) Fort Worth Water Gardens, designed by noted New York architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee, is an urban park containing three pools of water and terraced knolls; the Water Gardens are billed as a "cooling oasis in the concrete jungle" of downtown. Heritage Park Plaza is a Modernist-style park that was designed by Lawrence Halprin.[107] The plaza design incorporates a set of interconnecting rooms constructed of concrete and activated throughout by flowing water walls, channels, and pools and was added to the US National Register of Historic Places on May 10, 2010.[108]

There are two off-leash dog parks located in the city, ZBonz Dog Park and Fort Woof. The park includes an agility course, water fountains, shaded shelters, and waste stations.[109]

Sports

editWhile much of Fort Worth's sports attention is focused on Dallas's professional sports teams,[110] the city has its own athletic identity.

In 2021, it was announced that Austin Bold FC would relocate to Fort Worth, providing Fort Worth with a USL Championship club.[111] Semi-professionally, the Fort Worth Jaguars play in the North American Floorball League and the North Texas Bulls of the National Arena League play at Cowtown Coliseum.[112]

There are three amateur soccer clubs in Fort Worth: Fort Worth Vaqueros FC, Inocentes FC, and Azul City Premier FC; Inocentes and Azul City Premier both play in the United Premier Soccer League.[113] The Vaqueros play in the National Premier Soccer League.[114]

Collegiately, Texas Christian University's athletic teams are the premier college sports teams for Fort Worth. The TCU Horned Frogs compete in NCAA Division I athletics. The Horned Frog football team produced two national championships in the 1930s and remained a strong competitor in the Southwest Conference into the 1960s before beginning a long period of underperformance.[115]

The revival of the TCU football program began under Dennis Franchione with the success of running back LaDainian Tomlinson. Under Gary Patterson, the Horned Frogs have developed into a perennial top-10 contender, and a Rose Bowl winner in 2011.[116] Notable players include Sammy Baugh, Davey O'Brien, Bob Lilly, LaDainian Tomlinson, Jerry Hughes, and Andy Dalton. The Horned Frogs, along with their rivals and fellow non-AQ leaders the Boise State Broncos and University of Utah Utes, were deemed the quintessential "BCS Busters", having appeared in both the Fiesta and Rose bowls. Their "BCS Buster" role ended in 2012 when they joined the Big 12 athletic conference in all sports.

Nearby Texas Wesleyan University competes in the NAIA, and won the 2006 NAIA Div. I Men's Basketball Championship and three-time National Collegiate Table Tennis Association (NCTTA) team championships (2004–2006). Fort Worth is also home to the NCAA football Lockheed Martin Armed Forces Bowl.

There used to be one professional sports team in Fort Worth proper, Panther City Lacrosse Club of the National Lacrosse League. It was founded in 2020 and played at Dickies Arena[117] until it folded in 2024.

Recreation

editColonial National Invitational Golf Tournament

editFort Worth hosts an important professional men's golf tournament every May at the Colonial Country Club. The Colonial Invitational Golf Tournament, now officially known as the Fort Worth Invitational, is one of the more prestigious and historical events of the tour calendar. The Colonial Country Club was the home course of golfing legend Ben Hogan, who was from Fort Worth.[118]

Motor racing

editFort Worth is home to Texas Motor Speedway, also known as "The Great American Speedway". Texas Motor Speedway is a 1.5-mile quad-oval track located in the far northern part of the city in Denton County. The speedway opened in 1997, and currently hosts an IndyCar event and six NASCAR events among three major race weekends a year.[119][120]

Amateur sports-car racing in the greater Fort Worth area occurs mostly at two purpose-built tracks: MotorSport Ranch and Eagles Canyon Raceway. Sanctioning bodies include the Porsche Club of America, the National Auto Sports Association, and the Sports Car Club of America.

Cowtown Marathon

editThe annual Cowtown Marathon has been held every last weekend in February since 1978. The two-day activities include two 5Ks, a 10K, the half marathon, marathon, and ultra marathon.[121]

Rodeo

editIn addition to the weekly rodeos held at Cowtown Coliseum in the Stockyards, the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo is held within the Will Rogers Memorial Center at the Dickies Arena.[122][123] Dickies Arena also hosts a few TCU basketball games and in the future planned to host college basketball tournaments at the conference and national levels.

Government

editCity government

editFort Worth has a council-manager government, with elections held every two years for a mayor, elected at large, and eight council members, elected by district. The mayor is a voting member of the council and represents the city on ceremonial occasions. The council has the power to adopt municipal ordinances and resolutions, make proclamations, set the city tax rate, approve the city budget, and appoint the city secretary, city attorney, city auditor, municipal court judges, and members of city boards and commissions. The day-to-day operations of city government are overseen by the city manager, who is also appointed by the council.[124] The current mayor is Republican Mattie Parker, making Fort Worth the second-largest city in the United States with a Republican mayor.[125]

City Council

edit| Office[126] | Name[126] |

|---|---|

| Mayor | Mattie Parker |

| City Council, District 2 | Carlos Flores |

| City Council, District 3 | Michael Crain |

| City Council, District 4 | Cary Moon |

| City Council, District 5 | Gyna Bivens |

| City Council, District 6 | Jared Williams |

| City Council, District 7 | Leonard Firestone |

| City Council, District 8 | Chris Nettles |

| City Council, District 9 | Elizabeth Beck |

City departments

edit- Fort Worth Police Department – provides crime prevention, investigation, and other emergency services

- Fort Worth Fire Department – provides fire and emergency services

- Fort Worth Library – public library system of the City of Fort Worth

State government

editState Board of Education members

edit| District | Name[127] | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| District 11 | Patricia Hardy | Republican | |

| District 13 | Erika Beltran | Democratic | |

Texas State Representatives

edit| District | Name[127] | Party | Residence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District 61 | Phil King | Republican | Weatherford | |

| District 63 | Ben Bumgarner | Republican | Flower Mound | |

| District 90 | Ramon Romero Jr. | Democratic | Fort Worth | |

| District 91 | Stephanie Klick | Republican | Fort Worth | |

| District 92 | Salman Bhojani | Democratic | Bedford | |

| District 93 | Nate Schatzline | Republican | Fort Worth | |

| District 95 | Nicole Collier | Democratic | Fort Worth | |

| District 96 | David Cook | Republican | Mansfield | |

| District 97 | Craig Goldman | Republican | Fort Worth | |

| District 98 | Giovanni Capriglione | Republican | Southlake | |

| District 99 | Charlie Geren | Republican | River Oaks | |

Texas State Senators

edit| District | Name[127] | Party | Residence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District 9 | Kelly Hancock | Republican | Fort Worth | |

| District 10 | Phil King | Republican | Weatherford | |

| District 12 | Tan Parker | Republican | Flower Mound | |

| District 30 | Drew Springer | Republican | Muenster | |

State facilities

editThe Texas Department of Transportation operates the Fort Worth District Office in Fort Worth.[128]

The North Texas Intermediate Sanction Facility, a privately operated prison facility housing short-term parole violators, was in Fort Worth. It was operated on behalf of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. In 2011, the state of Texas decided not to renew its contract with the facility.[129]

Federal government

editUnited States House of Representatives

edit| District | Name[127] | Party | Residence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texas's 6th congressional district | Jake Ellzey | Republican | Waxahachie | |

| Texas's 12th congressional district | Kay Granger | Republican | Fort Worth | |

| Texas's 24th congressional district | Beth Van Duyne | Republican | Irving | |

| Texas's 26th congressional district | Michael Burgess | Republican | Lewisville | |

| Texas's 33rd congressional district | Marc Veasey | Democratic | Fort Worth | |

Federal facilities

editFort Worth is home to one of the two locations of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. In 1987, construction on this second facility began. In addition to meeting increased production requirements, a western location was seen to serve as a contingency operation in case of emergencies in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area; as well, costs for transporting currency to Federal Reserve banks in San Francisco, Dallas, and Kansas City would be reduced. Currency production began in December 1990 at the Fort Worth facility;[130] the official dedication took place April 26, 1991. Bills produced here have a small "FW" in one corner.

The Eldon B. Mahon United States Courthouse building contains three oil-on-canvas panels on the fourth floor by artist Frank Mechau (commissioned under the Public Works Administration's art program).[131] Mechau's paintings, The Taking of Sam Bass, Two Texas Rangers, and Flags Over Texas were installed in 1940, becoming the only New Deal art commission sponsored in Fort Worth. The courthouse, built in 1933, serves the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2001.[51]

Federal Medical Center, Carswell, a federal prison and health facility for women, is located in the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth.[132] Carswell houses the federal death row for female inmates.[133] Federal Medical Center, Ft. Worth, a federal prison and health facility for men, is located across from TCC-South Campus. The Federal Aviation Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, and Federal Bureau of Investigation have offices in Fort Worth.

Education

editPublic libraries

editFort Worth Public Library is the public library system.

Public schools

editMost of Fort Worth is served by the Fort Worth Independent School District.

Other school districts that serve portions of Fort Worth include:[134]

- Aledo Independent School District

- Arlington Independent School District (wastewater plant only[citation needed])

- Azle Independent School District

- Birdville Independent School District

- Burleson Independent School District

- Castleberry Independent School District

- Crowley Independent School District

- Eagle Mountain-Saginaw Independent School District

- Everman Independent School District

- Hurst-Euless-Bedford Independent School District

- Keller Independent School District

- Kennedale Independent School District

- Lake Worth Independent School District

- Northwest Independent School District

- White Settlement Independent School District

The portion of Fort Worth within the Arlington Independent School District contains a wastewater plant. No residential areas are in this portion.[citation needed]

Pinnacle Academy of the Arts (K–12) is a state charter school, as are Crosstimbers Academy and High Point Academy.

Private schools

editPrivate schools in Fort Worth include both secular and parochial institutions.

- All Saints' Episcopal School (Fort Worth, TX) (PreK–12)

- Bethesda Christian School (K–12)

- Covenant Classical School (K–12)

- Fort Worth Christian School (K–12)

- Fort Worth Country Day School (K–12)

- Lake Country Christian School (K–12)

- Montessori School of Fort Worth (Pre-K–8)

- Nolan Catholic High School (9–12)

- Trinity Valley School (K–12)

- Temple Christian School (Pre-K–12)

- Trinity Baptist Temple Academy (K–12)

- Hill School of Fort Worth (2–12)

- Southwest Christian School (K–12)

- St. Paul Lutheran School (K–8)

- The Roman Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth oversees several Catholic elementary and middle schools.[135]

Institutes of higher education

edit- Texas Christian University

- Texas Wesleyan University

- University of Texas at Arlington – Downtown Fort Worth campus

- University of North Texas Health Science Center

- TCU School of Medicine

- Texas A&M University School of Law

- Tarleton State University – Fort Worth campus

- Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

- Brite Divinity School

- Tarrant County College

Other institutions:

- The Art Institute of Fort Worth

- Brightwood College – Fort Worth Campus

- Fisher More College

- Remington College Fort Worth campus

- The Culinary School of Fort Worth

- Epic Helicopters Pilot Training Academy

Media

editFort Worth and Dallas share the same media market. The city's magazine is Fort Worth, Texas Magazine, which publishes information about Fort Worth events, social activity, fashion, dining, and culture.[136]

Fort Worth has one major daily newspaper, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, founded in 1906 as Fort Worth Star. It dominates the western half of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, and The Dallas Morning News dominates the east.[citation needed] In 2023, the publication's print circulation was 43,342.[137]

The Fort Worth Weekly is an alternative weekly newspaper for the Fort Worth metropolitan division. The newspaper had an approximate circulation of 47,000 in 2015.[138] The Fort Worth Weekly published and features, among many things, news reporting, cultural event guides, movie reviews, and editorials. Additionally, Fort Worth Business Press is a weekly publication that chronicles news in the Fort Worth business community.

The Fort Worth Report is a daily nonprofit news organization covering local government, business, education and arts in Tarrant County.[139] The nonprofit organization, founded by local business leaders and former Fort Worth Star-Telegram publisher Wes Turner,[140] announced its intentions in February 2021 and officially launched the newsroom in April 2021.[141][142]

The Fort Worth Press was a daily newspaper, published weekday afternoons and on Sundays from 1921 until 1975. It was owned by the E. W. Scripps Company and published under the then-prominent Scripps-Howard Lighthouse logo. The paper reportedly last made money in the early 1950s. Scripps Howard stayed with the paper until mid-1975. Circulation had dwindled to fewer than 30,000 daily, just more than 10% of that of the Fort Worth Star Telegram. The name Fort Worth Press was resurrected briefly in a new Fort Worth Press paper operated by then-former publisher Bill McAda and briefer still by William Dean Singleton, then-owner of the weekly Azle (Texas) News, now owner of the Media Central news group. The Fort Worth Press operated from offices and presses at 500 Jones Street in Downtown Fort Worth.[143]

Television stations shared with Dallas include (owned-and-operated stations of their affiliated networks are highlighted in bold) KDFW 4 (Fox), KXAS 5 (NBC), WFAA 8 (ABC), KTVT 11 (CBS), KERA 13 (PBS), KTXA 21 (Independent), KDFI 27 (MNTV), KDAF 33 (CW), and K07AAD-D (HC2 Holdings).

Radio stations

editOver 33 radio stations operate in and around Fort Worth, with many different formats.

AM

editOn the AM dial, like in all other markets, political talk radio is prevalent, with WBAP 820, KLIF 570, KSKY 660, KFJZ 870, KRLD 1080 the conservative talk stations serving Fort Worth and KMNY 1360 the sole progressive talk station serving the city. KFXR 1190 is a news/talk/classic country station. Sports talk can be found on KTCK 1310 ("The Ticket"). WBAP, a 50,000-watt clear-channel station which can be heard over much of the country at night, was a long-successful country music station before converting to its current talk format.

Several religious stations are also on AM in the Dallas/Fort Worth area; KHVN 970 and KGGR 1040 are the local urban gospel stations, KEXB 1440 carries Catholic talk programming from Relevant Radio, and KKGM 1630 has a Southern gospel format.

Fort Worth's Spanish-speaking population is served by many stations on AM:

A few mixed Asian language stations serve Fort Worth:

FM

editKLNO is a commercial radio station licensed to Fort Worth. Long-time Fort Worth resident Marcos A. Rodriguez operated Dallas-Fort Worth radio stations KLTY and KESS on 94.1 FM. Four urban-formatted radio stations, KBFB 97.9, KKDA 104.5, KRNB 105.7, and KZMJ 94.5, can also be heard. A wide variety of commercial formats, mostly music, are on the FM dial in Fort Worth.

Noncommercial stations serve the city fairly well. Three college stations can be heard - KTCU 88.7, KCBI 90.9, and KNTU 88.1, with a variety of programming. Also, the local NPR station is KERA 90.1, along with community radio station KNON 89.3. Downtown Fort Worth also hosts the Texas Country radio station KFWR 95.9 The Ranch.

Internet radio stations and shows

editWhen local radio station KOAI 107.5 FM, now KMVK, dropped its smooth jazz format, fans set up smoothjazz1075.com, an internet radio station, to broadcast smooth jazz for disgruntled fans.

Transportation

editLike most cities that grew quickly after World War II, Fort Worth's main mode of transportation is the automobile, but bus transportation via Trinity Metro is available, as well as an interurban train service to Dallas via the Trinity Railway Express. As of January 10, 2019, train service from Downtown Fort Worth to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport's Terminal B is available via Trinity Metro's TEXRail service.

History

editElectric streetcars

editThe first streeetcar company in Fort Worth was the Fort Worth Street Railway Company. Its first line began operating in December 1876, and traveled from the courthouse down Main Street to the T&P Depot.[144] By 1890, more than 20 private companies were operating streetcar lines in Fort Worth. The Fort Worth Street Railway Company bought out many of its competitors, and was eventually itself bought out by the Bishop & Sherwin Syndicate in 1901.[145] The new ownership changed the company's name to the Northern Texas Traction Company, which operated 84 miles of streetcar railways in 1925, and their lines connected downtown Fort Worth to TCU, the Near Southside, Arlington Heights, Lake Como, and the Stockyards.

Electric interurban railways

editAt its peak, the electric interurban industry in Texas consisted of almost 500 miles of track, making Texas the second in interurban mileage in all states west of the Mississippi River. Electric interurban railways were prominent in the early 1900s, peaking in the 1910s and fading until all electric interurban railways were abandoned by 1948. Close to three-fourths of the mileage was in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, running between Fort Worth and Dallas and to other area cities including Cleburne, Denison, Corsicana, and Waco. The line depicted in the associated image was the second to be constructed in Texas and ran 35 miles between Fort Worth and Dallas. Northern Texas Traction Company built the railway, which was operational from 1902 to 1934.[146]

Current transport

editIn 2009, 80.6% of Fort Worth (city) commuters drive to work alone. The 2009 mode share for Fort Worth (city) commuters are 11.7% for carpooling, 1.5% for transit, 1.2% for walking, and .1% for cycling.[147] In 2015, the American Community Survey estimated modal shares for Fort Worth (city) commuters of 82% for driving alone, 12% for carpooling, .8% for riding transit, 1.8% for walking, and .3% for cycling.[148] The city of Fort Worth has a lower than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 6.1 percent of Fort Worth households lacked a car, and decreased to 4.8 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Fort Worth averaged 1.83 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[149]

Roads

editFort Worth is served by four interstates and three U.S. highways. It also contains a number of arterial streets in a grid formation.

Interstate highways 30, 20, 35W, and 820 all pass through the city limits.

Interstate 820 is a loop of Interstate 20 and serves as a beltway for the city. Interstate 30 and Interstate 20 connect Fort Worth to Arlington, Grand Prairie, and Dallas. Interstate 35W connects Fort Worth with Hillsboro to the south and the cities of Denton and Gainesville to the north.

U.S. Route 287 runs southeast through the city connecting Wichita Falls to the north and Mansfield to the south. U.S. Route 377 runs south through the northern suburbs of Haltom City and Keller through the central business district. U.S. Route 81 shares a concurrency with highway 287 on the portion northwest of I-35W.

Notable state highways:

- Texas State Highway 114 (east-west)

- Texas State Highway 183 (east-west)

- Texas State Highway 121 (north-south)

Public transportation

editTrinity Metro, formerly known as the Fort Worth Transportation Authority, serves Fort Worth with dozens of different bus routes throughout the city, including a downtown bus circulator known as Molly the Trolley. In addition to Fort Worth, Trinity Metro operates buses in the suburbs of Blue Mound, Forest Hill, River Oaks and Sansom Park.[150]

In 2010, Fort Worth won a $25 million Federal Urban Circulator grant to build a streetcar system.[151] In December 2010, though, the city council forfeited the grant by voting to end the streetcar study.[152]

In July 2019, Trinity Metro partnered with Via Transportation to launch an on-demand microtransit service called ZIPZONE. ZIPZONE offers shared rides across the Alliance, Mercantile, Southside, and South Tarrant neighborhoods and was designed as a first-and-last mile connection for TEXRail and bus commuters.[153][154][155] Trips are booked from a smartphone app and charge a flat $3 for service as of April 2021. ZIPZONE rides are also included with multi-ride Trinity Metro local tickets.[156]

Rail transportation

edit- TEXRail is a commuter rail line opened in January 2019 that connects downtown Fort Worth with Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, with stops in the cities of Grapevine and North Richland Hills.

- Trinity Railway Express is a commuter rail line that operates between T&P Station in downtown Fort Worth and terminates at Dallas Union Station.[157]

- Two Amtrak routes stop at Fort Worth Central: Heartland Flyer and Texas Eagle.

Airports

editDallas Fort Worth International Airport is a major commercial airport located between the major cities of Fort Worth and Dallas. DFW Airport is the world's third-busiest airport based on operations and tenth-busiest airport based on passengers.[158]

Prior to the construction of the DFW Airport, the city was served by Greater Southwest International Airport, which was located just to the south of the new airport. Originally named Amon Carter Field after the publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Greater Southwest opened in 1953 and operated as the primary airport for Fort Worth until 1974. It was then abandoned until the terminal was torn down in 1980. The site of the former airport is now a mixed-use development straddled by Texas State Highway 183 and 360. One small section of runway remains north of Highway 183, and serves as the only reminder that a major commercial airport once occupied the site.

Fort Worth is home to these four airports within city limits:

- Fort Worth Alliance Airport

- Fort Worth Meacham International Airport

- Fort Worth Spinks Airport

- Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth

Walkability

editA 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Fort Worth 47th-most walkable of 50 largest U.S. cities.[159]

Notable people

editSister cities

editFort Worth is a part of the Sister Cities International program and maintains cultural and economic exchange programs with its sister cities:[160]

- Reggio Emilia, Emilia-Romagna, Italy (1985)

- Nagaoka, Niigata, Japan (1987)

- Trier, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany (1987)

- Bandung, West Java, Indonesia (1990)

- Budapest, Hungary (1990)

- Toluca, Estado de Mexico, Mexico (1998)

- Mbabane, Eswatini (2004)

- Guiyang, Guizhou, China (2010)

- Nîmes, Occitania, France (2019)

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Fort Worth Geographic Information Systems". Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b "From a cowtown to Cowtown". Fortworthgov.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ "Fort Worth, TX". tshaonline.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2011 : City of Fort Worth, Texas" (PDF). Fortworthtexas.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Fort Worth, Texas

- ^ a b "QuickFacts: Fort Worth city, Texas". World Population Review. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "QuickFacts: Fort Worth city, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Fort Worth, Texas Population 2024". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ McCann, Ian (July 10, 2008). "McKinney falls to third in rank of fastest-growing cities in U.S." The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010.

- ^ "Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington Has Largest Growth in the U.S". U.S. Census Bureau. March 22, 2018. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c Schmelzer, Janet (June 12, 2010). "Fort Worth, Texas". Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Fort Worth, from uTexas.com". Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ^ "International Programs: Fort Worth". Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ^ "Navy Names Littoral Combat Ship USS Fort Worth" (Press release). United States Department of Defense. March 6, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Kimbell Art Museum | Fort Worth Museums & Attractions". Visit Fort Worth. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ http://atlas.thc.state.tx.us/map/viewform.asp?atlas_num=5439004731 [dead link]

- ^ "Details for Site of Bird's Fort". Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ Garrett, Julia Kathryn (May 31, 2013). Fort Worth. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780875655260. Archived from the original on July 10, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Crimmins, M.L., 1943, "The First Line of Army Posts Established in West Texas in 1849," Abilene: West Texas Historical Association, Vol. XIX, pp. 121–127

- ^ "Fort Worth, TX". Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ Image of E. S. Terrell with note: "E. S. Terrell. Born May 24, 1812, in Murry [sic] County, Tenn. The first white man to settle in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1849. His wife was Lou Preveler. They had seven children. In 1869, the Terrells took up residence in Young County, Texas, where he died Nov 1, 1905. He is buried at True, Texas." Image on display in historical collection at Fort Belknap, Newcastle, Texas. Viewed November 13, 2008.

- ^ Shurr, Elizabeth; Hagler, Jack P. (July 2013). "A Brief History Of "Cowtown"". United States Institute for Theatre Technology, Inc. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ "History of Panther Mascot". The Panther Foundation. May 2009. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ "Badge of Fort Worth Police Department". Fort Worth Police Department. May 2009. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ "History". Fort Worth Stockyards. March 30, 2016. Archived from the original on November 2, 2006.

- ^ "Fort Worth, Texas". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ "Nilcs City, TX". Handbook of Texas Online. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Julia Kathryn Garrett, Fort Worth: A Frontier Triumph (Austin: Encino, 1972)

- ^ Mack H. Williams, In Old Fort Worth: The Story of a City and Its People as published in the News-Tribune in 1976 and 1977 (1977). Mack H. Williams, comp., The News-Tribune in Old Fort Worth (Fort Worth: News-Tribune, 1975)

- ^ a b c d e "Hell's Half Acre, Fort Worth". Handbook of Texas Online. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Hornung, Chuck (2016). Wyatt Earp's cow-boy campaign : the bloody restoration of law and order along the Mexican border, 1882. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 12.

- ^ Fort Worth Daily Democrat, April 10, 1878, April 18, 1879, July 18, 1881. Oliver Knight, Fort Worth, Outpost on the Trinity (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953). Leonard Sanders, How Fort Worth Became the Texasmost City (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1973). Richard F. Selcer, Hell's Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red Light District (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1991). F. Stanley, Stanley F. L. Crocchiola, Jim Courtright (Denver: World, 1957).

- ^ Tarrant County Coalition for Peace and Justice 2021.

- ^ "Recent Development of the Barnett Shale Play, Fort Worth Basin, by Kent A. Bowker, #10126 (2007)". Search & Discovery. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "In Fort Worth, gas boom fuels public outreach plan". Reuters. July 11, 2007. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ "Drilling for Natural Gas Faces Hurdle: Fort Worth". RealEstateJournal. April 29, 2005. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ National Weather Service statistics, "Tornados in North Texas, 1920–2009"

- ^ Christie, Les (June 28, 2007). "The fastest growing U.S. cities". CNN. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "America's Most Livable: Fort Worth, Texas". Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ Bilefsky, Dan (June 21, 2011). "For New Life, Blacks in City Head to South". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ "Fort Worth's fast growth finds its way into mayor's 'State of the City' address". WFAA. February 29, 2020. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c "2018 ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ "At least 6 dead in 133-car pileup in Fort Worth after freezing rain coats roads". February 12, 2021. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "6 Killed, Dozens Hurt as 130+ Vehicles Collide on 'Sheets of Ice' in Massive Fort Worth Pileup – NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth". February 11, 2021. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "6 Dead, Dozens Injured After Pileup Of Over 130 Vehicles On I-35W In Fort Worth – CBS Dallas / Fort Worth". Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "NWS Ft. Worth". NOAA. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Cross Timbers and Prairies Ecological Region". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ "Gas Well Drilling". City of Fort Worth, Texas. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ "Lake Worth (Trinity River Basin)". Texas Water Development Board. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Fort Worth Stockyards". Fort Worth Stockyards. Archived from the original on May 5, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Restaurants | Chef Tim Love Eat, Drink & Live Well". Chef Tim Love. March 5, 2020. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Bud (May 4, 2020). "It's time! Here's the list of what's open for Mother's Day, both dine-in and take-out". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Grapevine Vintage Railroad | Schedule & Tickets Here". City of Grapevine, Texas. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "Weekly Rodeo & Wild West Show - Stockyards Rodeo in Fort Worth, TX". Weekly Rodeo & Wild West Show - Stockyards Rodeo in Fort Worth, TX. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "home | Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame". TX Cowboy HOF. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "Country Music, Classic Rock, Bull Riding, Food, and Games at Billy Bob's Texas". Billy Bob's Texas. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "Fort Worth Herd Twice Daily Cattle Drive". Fort Worth Stockyards. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "History of Tanglewood". May 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Tanglewood". Fort Worth Magazine. March 9, 2017. Archived from the original on July 10, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Fort Worth, Texas Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Average and record temperatures and precipitation, Fort Worth, Texas". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "Daily and average temperatures for July, Fort Worth, Texas". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Average annual snowfall by month, NOAA. "Governor Lynch's Veto Message Regarding HB 218 | Press Releases | Governor John Lynch". Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "NWS Fort Worth-Home". Archived from the original on July 23, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "NOW Data-NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2009. Archived from the original on December 10, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ "Fort Worth, Texas, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Population Rebounds for Many Cities in Northeast and Midwest". May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "ACS 2018 Households and Families Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "ACS 2018 Annual Income Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "ACS 2018 Per Capita Income Estimate". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "ACS 2018 Poverty Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "American Community Survey 2010 Demographic and Housing Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "American Community Survey 2010 Households and Families Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "American Community Survey 2010 Annual Income Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "American Community Survey 2010 Poverty Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ "Fort Worth (city), Texas". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Texas - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Weinberg, Tessa (June 30, 2019). "Tarrant County's Hispanic, black and Asian populations keep growing, whites less so". Fort Worth-Star Telegram. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ "Fort Worth deemed one of the country's 25 most diverse cities by new report". CultureMap Fort Worth. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (March 14, 2022). "Fort Worth Among US Cities With Largest Growth in Black Population". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Ura, Alexa; Kao, Jason; Astudillo, Carla; Essig, Chris (August 12, 2021). "People of color make up 95% of Texas' population growth, and cities and suburbs are booming, 2020 census shows". The Texas Tribune. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "Census data shows widening diversity; number of White people falls for first time". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Tarrant County, TX - Congregational Membership Reports". Association of Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "Dallas County, TX - Congregational Membership Reports". Association of Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "First Christian Church". Visit Fort Worth. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Fort Worth Metropolitan Division, DFW - TX Congregational Membership Reports". Association of Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "Diocese History". Roman Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

Today the Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth has grown from 60,000 Catholics in 1969 to 1,200,000 Catholics. The Diocese comprises 92 Parishes and 17 Schools, with 132 Priests (67 are Diocesan), 106 Permanent Deacons and 48 Sisters.

- ^ "Churches". Texas Baptists. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "Find a Church". Southern Baptists of Texas Convention. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ Silliman, Daniel (November 16, 2022). "'Nondenominational' Is Now the Largest Segment of American Protestants". News & Reporting. Archived from the original on June 29, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "A 'Postdenominational' Era: Inside The Rise Of The Unaffiliated Church". Religion Unplugged. November 15, 2022. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "ISJL - Texas Fort Worth Encyclopedia". Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.