Fort Edmonton Park (sometimes referred to as "Fort Edmonton") is an attraction in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Named for the first enduring European post in the area of modern-day Edmonton, the park is the largest living history museum in Canada by area.[1] It includes both original and rebuilt historical structures representing the history of Edmonton (including that of Indigenous Peoples), and is staffed during the summer by costumed historical interpreters.

| |

| Established | 1974 |

|---|---|

| Location | Edmonton, Alberta |

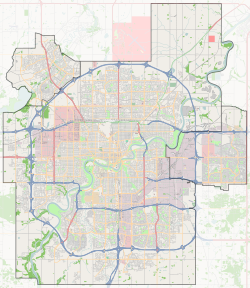

| Coordinates | 53°30′05″N 113°34′52″W / 53.50139°N 113.58111°W |

| Type | Living history |

| CEO | Darren Dalgleish |

| Owner | City of Edmonton |

| Public transit access | (to South Campus/Fort Edmonton Park station) |

| Website | Official website |

History

editThe history of Fort Edmonton Park's conception goes back as far as 1912 where the Women's Canadian Club proposed that they keep and preserve Fort Edmonton, which was still standing since 1830 just south of the Alberta Legislature Building. This idea however was unsuccessful,[2] and in 1915 the remains of the old fort were torn down, amidst opposition from citizens who wished to see the old structures relocated so that they could be cherished for their heritage value. A renewed interest after the Second World War began the momentum that saw the park begin construction in 1969 under the direction of the Fort Edmonton Foundation.

The Foundation's Master Plan of 1968 envisioned a park that would present a cross-section of the Edmonton area's history from the distant geological past, to the areas that it currently embodies, and even an area that would prophesy Edmonton's future. This original plan speculated that the completed park would be spread over ten phases. By 1987, however, it became clear that the park had evolved incompatibly with the ambitious 1968 plan, and the Master Plan was amended to focus instead on the four sections that had materialized to date.[3]

The fort was the first portion of the park to open in 1974, originally accessible directly by road. 1885 Street opened by the late 1970s, followed by 1905 Street in the early 1980s, and then 1920 Street by the beginning of the 1990s. A working steam train has transported visitors from the park's entrance to the fort since 1977. Each street was opened as a work in progress, and the latest version of the park's development plan calls for still more additions, especially to 1920 Street.[4]

Description

editAs of 2021, Fort Edmonton Park is made up of five sections, four of which represent an era, all spread over 158 acres (64 ha).[5] The park is located along the south bank of the North Saskatchewan River in southwestern Edmonton. The first section contains the Indigenous Peoples Experience, followed by a replica of the fort in 1846, 1885 Street, 1905 Street, and 1920 Street.[6] Visitors may board a fully functional steam train at the park's entrance which transports them across the length of the park to the fort, from which they proceed on foot and abstractly move forward through time by visiting all five areas.

Aside from the train, visitors may also ride horse-drawn carriages, and streetcars, in the appropriate eras. Rides on the train and streetcars are free with admission; however, rides on horse-drawn vehicles require a fee.

From May long weekend through to Labour Day, and Sundays in September, visitors may also interact with costumed historical interpreters. These personnel utilize a variety of techniques to reveal the lifestyles and attitudes of the era that they represent. Additionally, throughout the year, public tours may be booked with non-costumed interpreters.

Indigenous Peoples Experience (Pre-colonization–present)

editThe Indigenous Peoples Experience is the park's newest feature, and opened in 2021 after being constructed during the park's three-year renovation.[7] The museum immerses visitors in stories, lessons, cultures, and histories of various local First Nations and Métis communities through interactive exhibits, audio-visual displays, and music.[7] Throughout the building are stories and perspectives from more than 50 local Indigenous historians, elders, educators, and community members who were interviewed for this project.[8] In November 2021, Fort Edmonton Park received the "Thea Award for Outstanding Achievement - Heritage Center" for the exhibits in this museum, which were developed in partnership with members of the Confederacy of Treaty 6 Nations and the Métis Nation of Alberta.[9]

1846 Fort – Fur Trade Era (1795–1859)

editA full-scale replica of the eponymous Hudson's Bay Company Fort Edmonton represents the fur trade era. The replica fort was constructed using a scale plan diagram drawn by British Lieutenant Mervin Vavasour, who visited the Fort in the mid-1840s. Other accounts, such as the journals of the fort's denizens, or the artwork of Paul Kane, were used to flesh out the Vavasour Plan. A Cree camp is found just outside the fort's palisade, itself a representation of the indigenous First Nations, whose trade of furs and provisions was vital to the historical fort's operation.

Notable features

edit- York Boat

- A replica York boat is displayed near the river and is sometimes moored in the water. Another York boat may be seen under construction within the walls of the fort.

- The Rowand House

- The imposing residence of John Rowand and his family, this massive structure was one of the largest houses in present-day western Canada in its own time. The house has four levels, and they are (starting from the bottom): one for servants, one for dining and business, one for the family and guest rooms, and a garret for storage.

- The Men's Quarters

- Directly opposite of the Rowand House on the fort's courtyard, several apartments make up the residence of the Hudson's Bay Company's labourers. Some quarters are also the workspace of the fort's skilled tradesmen. Many beds furnish these quarters, as each small apartment was to house several working men and, if married, their families.

- The Clerks' Quarters

- Historically, this was a building for the fort's educated clerks to dwell in. The second floor, which would have had the clerks' bedrooms, was mistakenly not built in this reproduction. Instead, this building is almost entirely a dining hall, which would have been an important but not all-encompassing portion of the original. This building is among several in the park that are rented out for private functions.[10]

- The Indian House/Trade Store

- A common sight in Hudson's Bay Company posts, this was the point of trade for fur brought by natives who bartered them for European goods. The working men of the fort would toil in counting, storing and eventually transporting the furs to Hudson Bay, where they could be shipped to England and sold.

- Aboriginal camp

- To date, the main depiction of aboriginals in Fort Edmonton Park has been through a small Cree camp, located just outside the fort. One of the potential upcoming expansions for the park is a larger post-horse aboriginal village.[4]

1885 Street – The Settlement Era (1871–1891)

editWhile the fort may have been the first European establishment in the Edmonton area, it was not until the second half of the 19th century that settlers either moved out of the fort or came from some distance to work the land on self-sustaining farms. 1885 Street represents the beginning of a town, displays the establishment of telegraph and printing press media, and references major political events such as the North-West Rebellion of 1885.

Notable features

edit- Covered wagon

- This type of vehicle was used to carry settlers and their belongings overland from Winnipeg or Ontario. The wagons were made narrow to permit passage along the meagre trails.

- Jasper House Hotel

- While the original hotel is still in use by a different name at its original site in downtown Edmonton, Fort Edmonton Park's iteration reproduces the first building in the city to be made entirely of brick.[11] It is rented out for private functions.[10]

- McDougall Methodist Church

- An original structure that was moved to Fort Edmonton Park, this church, built in 1873, was one of the first structures built outside of Fort Edmonton.[12] It displays the prominence of Methodists in early Edmonton's community, a tradition carried on in this era by Reverend George McDougall from the first Protestant missionary in the region, Reverend Robert Rundle, who had lived in Fort Edmonton during its fur trade years.

- The North-West Mounted Police Outpost

- A replica of the office used by officers of the North-West Mounted Police (precursors to the present-day Royal Canadian Mounted Police).

- The Ottewell Homestead

- A reconstruction of an original house paired with an original barn from the same era,[13] this house is indicative of the lifestyle of the Dominion Lands Act homesteaders who populated the Edmonton area in the late 19th century. Live animals are kept at the site.

1905 Street – The Municipal Era (1892–1914)

editIn this time, Edmonton was established as a city, and in 1905 was selected as the site of the Alberta Provincial Legislature. This coincided with an economic boom that Edmonton enjoyed at the time. The darker side of the boom was that the lack of housing available necessitated a tent city, which may be seen on 1905 Street. Another important event in Edmonton, the opening of the University of Alberta in 1908, is often referenced on this street.

Notable features

edit- Tent City

- Due to Edmonton's economic boom in the early years of the 20th century, the large influx of newcomers to Edmonton arrived to find no housing available. Fort Edmonton Park's tent city reflects the temporary solution that people used until houses could be built. This historical reproduction found a contemporary parallel in 2007, when economic prosperity in the province of Alberta meant that many of the poor could not afford rising rent costs, and a tent city was erected in downtown Edmonton populated by about two hundred homeless people.[14]

- Rutherford House

- This was the house of Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the first Premier of Alberta and a major figure in the University of Alberta's inception. It was moved to Fort Edmonton Park from its original location in south Edmonton. It is distinct from Rutherford's later residence located on the University of Alberta campus.

Streetcar

Fort Edmonton Park streetcar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Streetcar

- The Edmonton Radial Railway Society operates a streetcar with service to both 1905 Street and 1920 Street. This service first becomes available at the junction of 1885 Street and 1905 Street. No fare is required to use the streetcar. Additionally, vintage automobiles may be seen operating on this street and 1920 Street.

- Masonic Hall

- Located at 1905 Street is a replica of a 1903 Masonic Hall, which was originally built at 100 Avenue and 102 Street. Opened in 1986, the Masonic Museum is located on the second floor and features Masonic regalia, furniture and historic artifacts.[15][16] Food services are located on the lower floor.[17][18]

1920 Street – The Metropolitan Era (1914–1929)

editThis street depicts Edmonton during and following the First World War. Whereas previous eras showed small businesses as making up nearly the entirety of Edmonton's commerce, Metropolitan Edmonton relies on larger business chains. Edmonton of this era also sports modern technology such as airplanes.

Notable features

edit- Blatchford Field Air Hangar

- A replica of the hangar at Edmonton City Centre Airport, which closed in 2013. Originally named Blatchford Field, it was the first "air harbour" in Canada.[19] This incarnation of the building doubles as a rental space for private functions.[10] A replica biplane like that flown by aviator Wop May will be displayed at the hangar site.[20]

- Hotel Selkirk

- An approximation of a hotel that once stood in the core of present-day downtown Edmonton, this building actually functions as a real hotel within the park, allowing visitors to stay overnight.[21]

- Mellon Farm

- This building is an original. It was located close by to its current location because the land that Fort Edmonton Park sits on was once owned by the Mellon family.[22]

- Al-Rashid Mosque

- The Al-Rashid Mosque is the first purpose-built mosque in Canada[23] and the oldest standing mosque in North America. Though it was built in 1938, outside of 1920 Street's apparent range, its move to Fort Edmonton Park saved it from demolition. Historically, many Muslim immigrants to Canada chose to live in Edmonton because a mosque was there.[24]

- 1920 Midway & Exhibition

- A recreation of a 1920s midway opened at the end of 1920 Street, near the park's entrance, in 2006. Various games of skill may be found on the midway, and a carousel featuring hand-carved horses is housed just inside a permanent pavilion nearby. The Fort Edmonton Foundation in 2008 expanded the Midway & Exhibition to include the Exhibits Building and other rides such as a Ferris wheel.[25]

In media

editFilms

edit- A 1978 film about Marie-Anne Gaboury, Marie-Anne, was shot at the fort.[26]

- The fort filled in for the fictional Hudson's Bay Company Fort Bailey in 2004's film Ginger Snaps Back: The Beginning.[27]

- The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford was filmed in the park in fall of 2005. Several locations in the park were used by the production, including the park's working steam train which was used in a robbery sequence; the train's interior was refurbished by the production crew for even more historical accuracy in a goodwill gesture to the park.[28] A paparazzo breached the production's security at the park, and was subsequently caught and arrested, while attempting to get a photograph of the film's star Brad Pitt.[29]

Television

edit- A 1981 SCTV sketch "SCTV Afterschool Special: Pepi Longsocks" with John Candy as the titular character was filmed at Fort Edmonton Park, using the fort, 1885 Street's Bellerose School and Egge's Stopping House, and 1905 Street's Henderson Round Barn as filming locations.[30]

- The Bryna Company and Astral Film Productions' made-for-television film Draw!, co-starring Kirk Douglas and James Coburn, was filmed at Fort Edmonton Park from August to October 1983.[31][32]

- The 2008 series premiere of Fear Itself, "The Sacrifice" primarily used Fort Edmonton and several of its buildings as filming locations for the fictional fort portrayed in the episode.[33]

- In 2015, the park's Kelly's Saloon served as the venue for a Roadblock task on the eleventh episode of the third season of The Amazing Race Canada.[34]

Affiliations

editThe museum is affiliated with: CMA, CHIN, and Virtual Museum of Canada.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Fort Edmonton". Albertatravel.org. Archived from the original on 2014-06-02. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ "River Valley West Central - Edmonton Historical Board". www.edmontonsarchitecturalheritage.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- ^ "Fort Edmonton Foundation". Fort Edmonton Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ a b "Fort Edmonton Foundation". Fort Edmonton Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ Fort Edmonton Park | Edmonton Sights Archived March 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Map". www.fortedmontonpark.ca. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ a b "Indigenous Peoples Experience among new offerings as Fort Edmonton Park reopens after $165M renovation - Edmonton | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ "Indigenous Peoples Experience". www.fortedmontonpark.ca. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ "Fort Edmonton Park receives international award for Indigenous exhibit". Edmonton. 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ a b c Fort Edmonton Park: Venue Rentals Archived 2009-02-13 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ "Jasper House Hotel". Ftedmontonpark.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ "Methodist Church". Ftedmontonpark.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ "Ottewell Homestead". Ftedmontonpark.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ^ Edmonton homeless pitch new tent city Archived January 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Masonic Hall, Alberta, Canada". The Masonic Tourist. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Early History Of Masonry In Alberta: Fort Edmonton Masonic Museum". Dominion Lodge #117. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Masonic Hall Museum - 56". Fort Edmonton Park Photos. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "A Tour of the Masonic Hall". Fort Edmonton Park. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Heritage Community Foundation: Blatchford Field Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Fort Edmonton Park: Blatchford Field Air Hangar[usurped] Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Fort Edmonton Park: Hotel Selkirk and Johnson's Cafe[usurped] Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Fort Edmonton Park: Mellon Farm[usurped] Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Canadian Society of Muslims: Al-Rashid Mosque Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Fort Edmonton Foundation: Al Raschid Mosque Archived 2008-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Fort Edmonton Foundation: 1920s Midway & Exhibition Archived 2008-02-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ IMDB.com: Marie Ann Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Canoe.ca: Invasion of Werewolves[usurped] Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Travel Alberta: Alberta Goes Hollywood...Again Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ Softpedia: Paparazzi Arrested On Brad Pitt's Movie Set Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine 13 September 2005

- ^ YouTube: Pepi Longsocks Retrieved on 31 January 2009

- ^ "Edmonton Journal from Edmonton, Alberta, Canada on August 16, 1983 · 1". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2021-06-19.

- ^ "The Leaf-Chronicle from Clarksville, Tennessee on October 23, 1983 · 47". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2021-06-19.

- ^ Edmonton Journal: New TV series dresses up local landmarks Archived 2009-08-18 at the Wayback Machine 4 June 2008

- ^ SPEROUNES, SANDRA. "Amazing Race Canada checks out Edmonton". Edmonton Journal. Postmedia Network. Retrieved 20 September 2015.