Angelo Fausto Coppi (Italian pronunciation: [ˈfausto ˈkɔppi]; 15 September 1919 – 2 January 1960) was an Italian cyclist, the dominant international cyclist of the years after the Second World War. His successes earned him the title Il Campionissimo ("Champion of Champions"). He was an all-round racing cyclist: he excelled in both climbing and time trialing, and was also a good sprinter. He won the Giro d'Italia five times (1940, 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953), the Tour de France twice (1949 and 1952), and the World Championship in 1953. Other notable results include winning the Giro di Lombardia five times, the Milan–San Remo three times, as well as wins at Paris–Roubaix and La Flèche Wallonne and setting the hour record (45.798 km) in 1942.

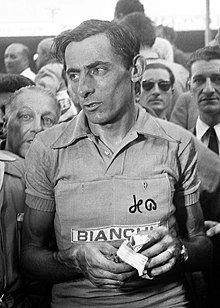

Coppi at the 1952 Tour de France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Angelo Fausto Coppi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | The Heron Il Campionissimo (Champion of Champions) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 15 September 1919 Castellania, Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2 January 1960 (aged 40) Tortona, Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.77 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 68 kg (150 lb; 10 st 10 lb) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Team information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Road and track | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Rider | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rider type | All-rounder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Professional teams | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1938–1939 | Dopolavoro Tortona | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1939–1942 | Legnano | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1945 | Cicli Nulli Roma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1945–1955 | Bianchi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1956–1957 | Carpano–Coppi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1958 | Bianchi–Pirelli | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1959 | Tricofilina–Coppi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Major wins | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grand Tours

Other

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early life and amateur career

editCoppi was born in Castellania (now known as Castellania Coppi), near Alessandria, one of five children born to Domenico Coppi and Angiolina Boveri,[1] who married on 29 July 1914. Fausto was the fourth child, born at 5:00 pm on 15 September 1919. His mother wanted to call him Angelo, but his father preferred Fausto. He was named Angelo Fausto but was known most of his life as Fausto.[2]

Coppi had poor health as a child and showed little interest in school. In 1927 he wrote "I ought to be at school, not riding my bicycle" after skipping lessons to spend the day riding a family bike which he had found in a cellar, rusty and without brake blocks.[3] He left school at age 13 to work for Domenico Merlani, a butcher in Novi Ligure more widely known as Signor Ettore.

Cycling to and from the shop and meeting cyclists who came there interested him in racing. The money to buy a bike came from his uncle, also called Fausto Coppi, and his father. Coppi said:

"... [My uncle] was a merchant navy officer on a petrol tanker, and a real cycling fan. He was touched when he heard of my passion for the bike and decided that I deserved a real tool for the job on which I had set my heart, instead of the rusty old crock I was pushing around. I just cried with joy when my kind uncle gave me the 600 lire that were to make my dream come true. I knew from advertisements I had seen in the local papers that for 600 lire I could get a frame built to my measurements in Genoa. Out of my slender savings I took enough for the train fare to Genoa and back, gave my measurements, and handed over the 600 lire. I would have to buy the fittings and tyres from my errand-boy salary. Oh how my legs used to ache at night through climbing all those stairs during the day! But I'm glad I did, because it surely made my legs so strong".[4] "Come back within a week; your frame will be ready" said the owner of the cycle shop".[4] "But it wasn't ready, and not the next week, and not the next. For eight weeks I threw precious money away taking the train to Genoa and still no made-to-measure bike for me. The fellow just couldn't be bothered making a frame for a skinny country kid who didn't look as if he could pedal a fairy-cycle, let alone a racing bike. I used to cry bitterly as I went back home without the frame. On the ninth journey I took a frame home. But it wasn't a 'made to measure'. The chap just took one down off the rack. I was furious inside, but too shy to do anything about it".[4]

Coppi rode his first race at age 15, among other boys not attached to cycling clubs, and won first prize: 20 lire and a salami sandwich. Coppi took a racing licence at the start of 1938 and won his first race, at Castelleto d'Orba, near the butcher's shop. He won alone, winning an alarm clock. A regular caller at the butcher's shop in Novi Ligure was a former boxer who had become a masseur, a job he could do after losing his sight, in 1938. Giuseppe Cavanna was known to friends as Biagio. Coppi met him that year, recommended by another of Cavanna's riders. Cavanna suggested in 1939 that Coppi should become an independent, a class of semi-professionals who could ride against both amateurs and professionals. He sent Coppi to the Tour of Tuscany that April with the advice: "Follow Gino Bartali!" He was forced to stop with a broken wheel. But at Varzi on 7 May 1939 he won one of the races counting to the season-long national independent championship. He finished seven minutes clear of the field and won his next race by six minutes.

Professional career

editHis first major success was in 1940, winning the Giro d'Italia at the age of 20. On 7 November 1942 he set a world hour record (45.798 km at the Velodromo Vigorelli in Milan).[5] He rode a 7.40-metre (291-inch) gear and pedalled with an average cadence of 103.3 rpm.[6] The bike is on display in the chapel of Madonna del Ghisallo near Como, Italy.[7] Coppi beat Maurice Archambaud's 45.767 km, set five years earlier on the same track.[8] The record stood until it was beaten by Jacques Anquetil in 1956.[9] His career was then interrupted by active service in the Second World War. In 1946 he resumed racing and achieved remarkable successes which would be exceeded only by Eddy Merckx. The veteran writer Pierre Chany said that from 1946 to 1954 Coppi was never once recaught once he had broken away from the rest.[10]

Twice, 1949 and 1952, Coppi won the Giro d'Italia and the Tour de France in the same year, the first to do so. He won the Giro five times, a record shared with Alfredo Binda and Eddy Merckx. During the 1949 Giro he left Gino Bartali by 11 minutes between Cuneo and Pinerolo. Coppi won the 1949 Tour de France by almost half an hour over everyone except Bartali. From the start of the mountains in the Pyrenees to their end in the Alps, Coppi took back the 55 minutes by which Jacques Marinelli led him.[11]

Coppi won the Giro di Lombardia a record five times (1946, 1947, 1948, 1949 and 1954). He won Milan–San Remo three times (1946, 1948 and 1949). In the 1946 Milan–San Remo he attacked with nine others, five kilometres into a race of 292 km. He dropped the rest on the Turchino climb and won by 14 minutes.[12][9] He also won Paris–Roubaix and La Flèche Wallonne (1950). He was also 1953 world road champion.

In the first years of his career, Coppi was unable to ride the Tour de France. When he turned professional in 1940, the Tour de France was not held because of the Second World War. The Tour restarted in 1947, but Italians were not welcome yet. In 1948, Italians were welcome, but Coppi was suspended by the Italian cycling union because he had abandoned the 1948 Giro d'Italia in protest against the small penalty given to Fiorenzo Magni. In 1949, Coppi was finally able to enter the Tour. After several stages, Coppi was more than half an hour behind in the general classification, but he gained time in the mountain stages, and ended the Tour winning the general classification and the mountains classification, both with his teammate Bartali in second place, also winning the team classification.

In 1950, Coppi did not defend his Tour title, because he refused to ride together with Bartali. In 1951, he joined (riding together with Bartali), but was still affected by the death of his brother Serse Coppi, and did not excel.

In 1952, Coppi started again in the Tour. He won on the Alpe d'Huez, which had been included for the first time that year. He attacked six kilometres from the summit to rid himself of the French rider, Jean Robic. Coppi said: "I knew he was no longer there when I couldn't hear his breathing any more or the sound of his tyres on the road behind me".[13][14] He rode like "a Martian on a bicycle", said Raphaël Géminiani. "He asked my advice about the gears to use, I was in the French team and he in the Italian, but he was a friend and normally my captain in our everyday team, so I could hardly refuse him. I saw a phenomenal rider that day".[15] Coppi won the Tour by 28m 27s and the organiser, Jacques Goddet, had to double the prizes for lower placings to keep other riders interested.[16] It was his last Tour, having ridden three and won two. To conserve energy, he would have soigneurs carry him around his hotel during Grand Tours.[17]

Bill McGann wrote:

Comparing riders from different eras is a risky business subject to the prejudices of the judge. But if Coppi isn't the greatest rider of all time, then he is second only to Eddy Merckx. One can't judge his accomplishments by his list of wins because World War II interrupted his career just as World War I interrupted that of Philippe Thys. Coppi won it all: the world hour record, the world championships, the grands tours, classics as well as time trials. The great French cycling journalist, Pierre Chany says that between 1946 and 1954, once Coppi had broken away from the peloton, the peloton never saw him again. Can this be said of any other racer? Informed observers who saw both ride agree that Coppi was the more elegant rider who won by dint of his physical gifts as opposed to Merckx who drove himself and hammered his competition relentlessly by being the very embodiment of pure will.[18]

In 1955 Coppi and his lover Giulia Occhini were put on trial for adultery, then illegal in Italy, and got suspended sentences. The scandal rocked conservative ultra-Catholic Italy and Coppi was disgraced.[19] Coppi's career declined after the scandal. He had already been hit in 1951 by the death of his younger brother, Serse Coppi, who crashed in a sprint in the Giro del Piemonte and died of a cerebral haemorrhage.[n 1] Coppi could never match his old successes. Pierre Chany said he was first to be dropped each day in the Vuelta a España in 1959. Criterium organisers frequently cut their races to 45 km to be certain that Coppi could finish, he said. "Physically, he wouldn't have been able to ride even 10km further. He charged himself [took drugs] before every race". Coppi, said Chany, was "a magnificent and grotesque washout of a man, ironical towards himself; nothing except the warmth of simple friendship could penetrate his melancholia. But I'm talking of the end of his career. The last year! In 1959! I'm not talking about the great era. In 1959, he wasn't a racing cyclist any more. He was just clinging on [il tentait de sauver les meubles]."[20]

Jacques Goddet wrote in an appreciation of Coppi's career in L'Équipe: "We would like to have cried out to him 'Stop!' And as nobody dared to, destiny took care of it."

Raphaël Géminiani said of Coppi's domination:

When Fausto won and you wanted to check the time gap to the man in second place, you didn't need a Swiss stopwatch. The bell of the church clock tower would do the job just as well. Paris–Roubaix? Milan–San Remo? Lombardy? We're talking 10 minutes to a quarter of an hour. That's how Fausto Coppi was.[21]

Rivalry with Bartali

edit"This mercurial beginner [Fausto Coppi] joined Bartali's team in 1940, and then won the Giro d'ltalia with a massive lead over his team leader. Bartali was astonished and affronted.

Henceforward, the two riders were in personal combat—it often seemed that, as fierce rivals, they cared less about winning a race than beating each other".

Tim Hilton, The Guardian[22]

Coppi's racing days are generally referred to as the beginning of the golden years of cycle racing. A factor is the competition between Coppi and Gino Bartali. Italian tifosi (fans) divided into coppiani and bartaliani. Bartali's rivalry with Coppi divided Italy.[23] Bartali, conservative, religious, was venerated in the rural, agrarian south, while Coppi, more worldly, secular, innovative in diet and training, was hero of the industrial north. The writer Curzio Malaparte said:

"Bartali belongs to those who believe in tradition ... he is a metaphysical man protected by the saints. Coppi has nobody in heaven to take care of him. His manager, his masseur, have no wings. He is alone, alone on a bicycle ... Bartali prays while he is pedalling: the rational Cartesian and sceptical Coppi is filled with doubts, believes only in his body, his motor".

Their lives came together on 7 January 1940 when Eberardo Pavesi, head of the Legnano team, took on Coppi to ride in support of Bartali. Their rivalry started when Coppi, the helping hand, won the Giro and Bartali, the star, marshalled the team to chase. By the 1948 world championship at Valkenburg, Limburg in the Netherlands, both climbed off rather than help the other. The Italian cycling association said: "They have forgotten to honour the Italian prestige they represent. Thinking only of their personal rivalry, they abandoned the race, to the approbation of all sportsmen". They were suspended for three months.[24]

The thaw partly broke when the pair shared a bottle on the Col d'Izoard in the 1952 Tour[n 2] but the two fell out over who had offered it. "I did", Bartali insisted. "He never gave me anything".[25] Their rivalry was the subject of intense coverage and resulted in epic races.

Life during World War II

editCoppi joined the Italian Army when Italy entered World War II: the declaration of war on the Allied Powers was made on the day after the finish of the 1940 Giro d'Italia.[26] Officers initially supported him continuing his riding career: track cycling and one-day racing continued during the war, and Coppi continued to enjoy success, winning the Giro di Toscana, the Giro dell'Emilia and Tre Valli Varesine on the road in 1941, along with the Italian national pursuit title on the track. He struggled at the beginning of the following year following the death of his father, but became national road champion after suffering a puncture and losing one and a half minutes to the bunch, forcing him into a solo chase to rejoin the peloton. The following week he broke his collarbone in a crash before he was due to defend his national pursuit championship in the final against Cino Cinelli: however, Cinelli refused to accept the title by default, and the final was delayed to October, which Coppi won. Shortly afterwards he made his successful bid for the hour record at Vigorelli Velodrome: the roof of the building still had large holes after Milan had been heavily bombed a few weeks earlier.[26]

However, in March 1943 Coppi was sent to North Africa to participate in the Tunisian campaign, fighting against British forces. According to Coppi's identification paper, he was captured on 13 May 1943 in Enfidha, 100 km south of Tunis, although he may have been caught the previous month by the British Eighth Army which was in and around the city at that time. He was kept in the nearby prisoner of war camp at Ksar Saïd. In the camp he met other cyclists, including Silvio Pedroni, who had previously given Coppi a tyre after the latter had suffered a puncture in a race in 1939, and Ilio Simoni, who would later become a team-mate of Coppi's at Bianchi.[26] He also shared plates with the father of Claudio Chiappucci, who rode the Tour in the 1990s. He was given odd jobs to do. The British cyclist Len Levesley said he was astonished to find Coppi giving him a haircut.[27] Levesley, who was on a stretcher with polio, said:

"I should think it took me all of a full second to realise who it was. He looked fine, he looked slim, and having been in the desert, he looked tanned. I'd only seen him in cycling magazines but I knew instantly who he was. So he cut away at my hair and I tried to have a conversation with him, but he didn't speak English and I don't speak Italian. But we managed one or two words and I got over to him that I did some club racing. And I gave him a bar of chocolate that I had with me and he was grateful for that and that was the end of it".[n 3]

In April 1944, Coppi fell ill with malaria, however this was quickly diagnosed and treated. In November of that year he returned to Italy, arriving at a POW camp in Naples to work as a driver for the Royal Air Force.[26] The British moved Coppi to an RAF base at Caserta in Italy, based in the city's royal palace, in 1945.[26] There he worked as a truck driver and as a personal assistant and handyman for an officer, Lieutenant Ronald Smith Towell,[26] who had never heard of him. Despite this, the two struck up a mutually beneficial relationship: Coppi's popularity in Italy was helpful to Towell in achieving his goals as an administrator, whilst Towell was able, via S.S.C. Napoli footballer Umberto Busani, to help Coppi make contact with local sports journalist Gino Palumbo, who would later become editor of La Gazzetta dello Sport. Coppi wrote to Palumbo asking if he could assist with obtaining a racing bicycle for him as he only had an army bicycle with heavy tyres which was causing him pain. Palumbo wrote a newspaper article appealing for help: Coppi then received a Legnano racing bike from a Somma Vesuviana carpenter.[26]

The war being as good as over, Coppi was released in 1945. In addition he had distanced himself from Mussolini's government during his time in British custody, which often resulted in beneficial treatment compared to those who had continued to profess their loyalty to the Fascist regime.[26] On release he cycled and hitched lifts home. On Sunday 8 July 1945 he won the Circuit of the Aces in Milan after four years away from racing. The following season he won Milan–San Remo.[28]

Personal life

editCoppi's beloved, "The Woman in White" was Giulia Occhini, described by the French broadcaster Jean-Paul Ollivier as "strikingly beautiful with thick chestnut hair divided into enormous plaits". She was married to an army captain, Enrico Locatelli. Coppi was married to Bruna Ciampolini. Locatelli was a cycling fan. His wife wasn't but she joined him on 8 August 1948 to see the Tre Valli Varesine race. Their car was caught beside Coppi's in a traffic jam. That evening Occhini went to Coppi's hotel and asked for a photograph. He wrote "With friendship to ...", asked her name and then added it. From then on the two spent more and more time together.

Italy was a straight-laced country in which adultery was thought of poorly. In 1954, Luigi Boccaccini of La Stampa saw her waiting for Coppi at the end of a race in St-Moritz. She and Coppi hugged and La Stampa printed a picture in which she was described as la dama in bianco di Fausto Coppi—the "woman in white of Fausto Coppi".

It took only a while to find out who she was. She and Coppi moved in together but so great was the scandal that the landlord of their apartment in Tortona demanded they move out. Reporters pursued them to a hotel in Castelletto d'Orba and again they moved, buying the Villa Carla, a house near Novi Ligure. There police raided them at night to see if they were sharing a bed. Pope Pius XII asked Coppi to return to his wife. He refused to bless the Giro d'Italia when Coppi rode it. The Pope then went through the Italian cycling federation. Its president, Bartolo Paschetta, wrote on 8 July 1954: "Dear Fausto, yesterday evening St. Peter made it known to me that the news [of adultery] had caused him great pain".

Bruna Ciampolini refused a divorce. To end a marriage was shameful and still illegal in the country. Coppi was shunned and spectators spat at him. He and Giulia Occhini had a son, Faustino.[29]

Death

editIn December 1959, the president of the Republic of Upper Volta (now known as Burkina Faso), Maurice Yaméogo, invited Coppi, Raphaël Géminiani, Jacques Anquetil, Louison Bobet, Roger Hassenforder and Henry Anglade to ride against local riders and then go hunting. Géminiani remembered:

"I slept in the same room as Coppi in a house infested by mosquitos. I'd got used to them but Coppi hadn't. Well, when I say we 'slept', that's an overstatement. It was like the safari had been brought forward several hours, except that for the moment we were hunting mosquitos. Coppi was swiping at them with a towel. Right then, of course, I had no clue of what the tragic consequences of that night would be. Ten times, twenty times, I told Fausto 'Do what I'm doing and get your head under the sheets; they can't bite you there'".[30]

Both caught malaria and fell ill when they got home. Géminiani said:

"My temperature got to 41.6 °C ... I was delirious and I couldn't stop talking. I imagined or maybe saw people all round but I didn't recognise anyone. The doctor treated me for hepatitis, then for yellow fever, finally for typhoid".[30]

Géminiani was diagnosed as being infected with plasmodium falciparum, one of the more lethal strains of malaria. Géminiani recovered but Coppi died, his doctors convinced he had a bronchial complaint. La Gazzetta dello Sport, the Italian daily sports paper, published a Coppi supplement. The editor wrote that he prayed that God would soon send another Coppi.[31] Coppi was an atheist.[32]

In January 2002 a man identified only as Giovanni, who lived in Burkina Faso until 1964, said Coppi died not of malaria but of an overdose of cocaine. The newspaper Corriere dello Sport said Giovanni had his information from Angelo Bonazzi. Giovanni said: "It is Angelo who told me that Coppi had been killed. I was a supporter of Coppi, and you can imagine my state when he told me that Coppi had been poisoned in Fada Gourma, at the time of a reception organised by the head of the village. Angelo also told me that [Raphael] Géminiani was also present... Fausto's plate fell, they replaced it, and then..."[33]

The story has also been attributed to a 75-year-old Benedictine monk called Brother Adrien. He told Mino Caudullo of the Italian National Olympic Committee: "Coppi was killed with a potion mixed with grass. Here in Burkina Faso this awful phenomenon happens. People are still being killed like that". Coppi's doctor, Ettore Allegri, dismissed the story as "absolute drivel".[34][35]

A court in Tortona opened an investigation and asked toxicologists about exhuming Coppi's body to look for poison. A year later, without exhumation, the case was dismissed.[36]

Legacy

editThe Giro remembers Coppi as it goes through the mountain stages. A mountain bonus, called the Cima Coppi, is awarded to the first rider who reaches the Giro's highest summit. In 1999, Coppi placed second in balloting for greatest Italian athlete of the 20th century.

Coppi's life story was depicted in the 1995 TV movie, Il Grande Fausto, written and directed by Alberto Sironi. Coppi was played by Sergio Castellitto and Giulia la 'Dama Bianca' (The Woman in White) was played by Ornella Muti.[37]

A commonly repeated trope is that when Coppi was asked how to be a champion, his reply was: "Just ride. Just ride. Just ride."[38] An Italian Restaurant in Belfast, designed with road bike parts and pictures, is named Coppi. Asteroid 214820 Faustocoppi was named in his memory in December 2017.

The village of his birth, previously known as 'Castellania', was renamed Castellania Coppi by the Piemont regional council in 2019, in preparation for the centenary of his birth.[39]

Doping

editGino Bartali took to raiding Coppi's room before races:

"The first thing was to make sure I always stayed at the same hotel for a race, and to have the room next to his so I could mount a surveillance. I would watch him leave with his mates, then I would tiptoe into the room which ten seconds earlier had been his headquarters. I would rush to the waste bin and the bedside table, go through the bottles, flasks, phials, tubes, cartons, boxes, suppositories – I swept up everything.

I became so expert in interpreting all these pharmaceuticals that I could predict how Fausto would behave during the course of the stage. I would work out, according to the traces of the product I found, how and when he would attack me".

Gino Bartali, Miroir des Sports, 1946,[40]

Coppi was often said to have introduced "modern" methods to cycling, particularly his diet. Gino Bartali established that some of those methods included taking drugs, which were not then against the rules.

Bartali and Coppi appeared on television revues and sang together, Bartali singing about "The drugs you used to take" as he looked at Coppi. Coppi spoke of the subject in a television interview:

- Question: Do cyclists take la bomba (amphetamine)?

- Answer: Yes, and those who claim otherwise, it's not worth talking to them about cycling.

- Question: And you, did you take la bomba?

- Answer: Yes. Whenever it was necessary.

- Question: And when was it necessary?

- Answer: Almost all the time![41][42]

Coppi "set the pace" in drug-taking, said his contemporary Wim van Est.[43] Rik Van Steenbergen said Coppi was "the first I knew who took drugs".[44] That didn't stop Coppi's protesting against others using it. He told René de Latour:

"What is the good of having world champions if those boys are worn out before turning professional? Maybe the officials are proud to come back with a rainbow jersey.[n 4] but if this is done at the expense of the boys' futures, then I say it's wrong. Do you think it normal that our best amateurs become nothing but 'gregari'?"[n 5][45]

Career achievements

editMajor results

edit- 1939

- 2nd Coppa Bernocchi

- 3rd Giro dell'Appennino

- 3rd Giro del Piemonte

- 1940

- 1st Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stage 11

- 3rd Giro del Lazio

- 3rd Tre Valli Varesine

- 9th Giro dell'Emilia

- 9th Giro di Campania

- 1941

- 1st Giro di Toscana

- 1st Giro dell'Emilia

- 1st Giro del Veneto

- 1st Tre Valli Varesine

- 4th Giro di Lazio

- 5th Giro di Lombardia

- 10th Milan–San Remo

- 10th Coppa Bernocchi

- 1942

- 1st National Road Race Championship

- 4th Giro del Lazio

- 5th Giro di Toscana

- 5th Giro dell'Emilia

- 7th Giro di Lombardia

- 10th Giro di Campania

- 1945

- 5th Milano–Torino

- 1946

- 1st Milan–San Remo

- 1st Giro di Lombardia

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Giro della Romagna

- 2nd Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st stages 4, 13 & 14

- 2nd Mountains classification

- 2nd Giro del Lazio

- 2nd Züri-Metzgete

- 1947

- 1st Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stages 4, 8 & 16

- 2nd Mountains classification

- 1st Giro di Lombardia

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st National Road Race Championship

- 1st Giro dell'Emilia

- 1st Giro della Romagna

- 1st Giro del Veneto

- 1st Individual pursuit, Road World Championships

- 5th Overall Tour de Suisse

- 1st Stage 5b

- 1948

- Giro d'Italia

- 1st Mountains classification

- 1st Stages 16 & 17

- 1st Milan–San Remo

- 1st Giro dell'Emilia

- 1st Tre Valli Varesine

- 1st Giro di Lombardia

- 2nd Het Volk

- 2nd Individual pursuit, Road World Championships

- 5th Giro di Toscana

- 1949

- 1st Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Mountains classification

- 1st Stages 4, 11 & 17

- 1st Overall Tour de France

- 1st Mountains classification

- 1st Stages 7, 17 & 20

- 1st Milan–San Remo

- 1st Giro di Lombardia

- 1st National Road Race Championship

- 1st Giro della Romagna

- 1st Giro del Veneto

- 1st Individual pursuit, Road World Championships

- 2nd Critérium des As

- 2nd Giro del Piemonte

- 3rd La Flèche Wallonne

- 3rd Road race, Road World Championships

- 1950

- 1st Paris–Roubaix

- 1st La Flèche Wallonne

- 1st Giro della Provincia di Reggio Calabria

- 2nd Trofeo Baracchi (with Serse Coppi)

- 3rd Giro di Lombardia

- 5th Giro del Piemonte

- 9th Milan–San Remo

- 1951

- 1st Gran Premio di Lugano

- 3rd Giro di Lombardia

- 4th Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stages 6 & 18

- 2nd Mountains classification

- 4th Critérium des As

- 4th Trofeo Baracchi (with Wim Van Est)

- 10th Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stage 20

- 3rd Mountains classification

- 1952

- 1st Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stages 5, 11 & 14

- 2nd Mountains classification

- 1st Overall Tour de France

- 1st Mountains classification

- 1st Stages 7, 10, 11, 18 & 21

- 1st Gran Premio di Lugano

- 2nd Paris–Roubaix

- 3rd Giro dell'Emilia

- 3rd Trofeo Baracchi (with Michele Gismondi)

- 4th Overall Tour de Romandie

- 1953

- 1st Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stages 4, 11 (TTT), 19 & 20

- 2nd Mountains classification

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Riccardo Filippi)

- 1st Road race, Road World Championships

- 9th Milan–San Remo

- 1954

- 1st Giro di Lombardia

- 1st Coppa Bernocchi

- 1st Giro di Campania

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Riccardo Filippi)

- 4th Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Mountains classification

- 1st Stage 20

- 4th Milan–San Remo

- 5th Overall Tour de Suisse

- 1st Stages 2 & 4

- 6th Road race, Road World Championships

- 1955

- 1st Giro dell'Appennino

- 1st Tre Valli Varesine

- 1st National Road Race Championship

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Riccardo Filippi)

- 1st Giro di Campania

- 2nd Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stage 20

- 2nd Paris–Roubaix

- 3rd Overall Roma–Napoli–Roma

- 1st Stage 5

- 4th Milano–Torino

- 5th Giro della Provincia di Reggio Calabria

- 1956

- 1st Gran Premio di Lugano

- 2nd Trofeo Baracchi (with Riccardo Filippi)

- 2nd Coppa Bernocchi

- 2nd Giro di Lombardia

- 9th Milano–Vignola

- 1957

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Ercole Baldini)

- 1958

- 7th Tre Valli Varesine

- 9th Giro del Piemonte

- 1959

- 5th Trofeo Baracchi (with Louison Bobet)

Grand Tour results timeline

editSource:[47]

| 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949 | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giro d'Italia | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | DNF | 1 | DNF | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | DNF | DNE | 32 | DNE |

| Stages won | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — | 0 | — | |||||

| Mountains classification | NR | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | NR | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | — | NR | — | NR | — | |||||

| Points classification | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | NR | — | NR | — | |||||

| Tour de France | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | DNE | DNE | 1 | DNE | 10 | 1 | DNE | DNE | DNE | DNE | DNE | DNE | DNE |

| Stages won | — | — | 3 | — | 1 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| Mountains classification | — | — | 1 | — | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| Points classification | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| Vuelta a España | N/A | DNE | DNE | N/A | N/A | DNE | DNE | DNE | DNE | N/A | DNE | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | DNE | DNE | DNE | DNE | DNF |

| Stages won | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | ||||||||

| Mountains classification | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | NR | ||||||||

| Points classification | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | — | — | — | NR |

| 1 | Winner |

| 2–3 | Top three-finish |

| 4–10 | Top ten-finish |

| 11– | Other finish |

| DNE | Did not enter |

| DNF-x | Did not finish (retired on stage x) |

| DNS-x | Did not start (not started on stage x) |

| HD | Finished outside time limit (occurred on stage x) |

| DSQ | Disqualified |

| N/A | Race/classification not held |

| NR | Not ranked in this classification |

Monuments results timeline

edit| Monument | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949 | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milan–San Remo | 17 | 10 | 21 | — | N/A | N/A | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 9 | — | 37 | 9 | 4 | 63 | — | — | — | — |

| Tour of Flanders | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Paris–Roubaix | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | — | — | — | — | — | 12 | 1 | — | 2 | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | 44 |

| Liège–Bastogne–Liège | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | N/A | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Giro di Lombardia | 16 | 5 | 7 | N/A | N/A | — | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 35 | — | 1 | 11 | 2 | — | — | — |

| — | Did not compete |

|---|---|

| N/A | Race not held |

See also

edit- Legends of Italian sport - Walk of Fame

- Cycling records

- Doping at the Tour de France

- Italy at the UCI Road World Championships

- List of doping cases in cycling

- List of Giro d'Italia classification winners

- List of Giro d'Italia general classification winners

- List of Grand Tour general classification winners

- List of Italians

- List of Tour de France general classification winners

- List of Tour de France secondary classification winners

- Pink jersey statistics

- Tour de France records and statistics

- Yellow jersey statistics

Notes

edit- ^ A parallel with Bartali, who also lost a brother, Giulio, in a 1936 racing accident.

- ^ Henry Anglade created a stained glass window of the incident; it is at the Notre Dame des Cyclistes chapel near Mont de Marsan, France.

- ^ His cycling friends called him Holy Head for years afterwards.

- ^ The award, along with a gold medal, given to the winner of a world championship.

- ^ "Gregari are team riders, employed to help their better riders win. A gregārius was a soldier of the Roman legions, 'one into the group'. They are equivalent to domestiques in the English-speaking world, équipiers in France and knechten 'servants' or 'helpers' in Belgium and the Netherlands.

References

edit- ^ Ollivier 1981.

- ^ Ollivier 1981, p. 12.

- ^ Ollivier 1981, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Sporting Cyclist, UK, undated cutting

- ^ Clemitson, Suze (19 September 2014). "Why Jens Voigt and a new group of cyclists want to break the Hour record". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "The Hour Record". Wolfgang-menn.de. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "www.cyclingnews.com - the world centre of cycling". autobus.cyclingnews.com.

- ^ "News and analysis". Autobus.cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Dave Moulton's Blog - Dave Moulton's Bike Blog - Fausto Coppi: Il Campionissimo". davesbikeblog.squarespace.com.

- ^ L'Équipe, France, 1960, cited Penot, Christophe (1996), Pierre Chany, l'homme aux 50 Tours de France, Cristel, France, ISBN 2-9510116-0-1, p. 805

- ^ Ollivier 1981, p. 85.

- ^ Penot, Christophe (1996), Pierre Chany, l'homme aux 50 Tours de France, Cristel, France, ISBN 2-9510116-0-1, p. 76

- ^ Vélo, France, June 2004

- ^ L'Équipe Magazine, 17 July 2004

- ^ Chany, Pierre (1988), La Fabuleuse Histoire de Tour de France, 1988, p. 408

- ^ McGann & McGann 2006, p. 187.

- ^ Velominati (Keepers of the Cog) (2013). The Rules: The way of the cycling disciple. London: Sceptre. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-444-76751-3.

- ^ McGann & McGann 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Robinson, Mark (15 January 2012). "Fausto Coppi: the triumphs and the tragedies". cyclingnews.com.

- ^ Cited de Mondenard, Jean-Pierre (2000), Dopage — l'imposture des Performances, Chiron, France, ISBN 2-7027-0639-8, p. 178

- ^ Cycle Sport, UK, November 1996, p. 72

- ^ Hilton, Tim (9 May 2000). "Gino Bartali". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Cycling Plus, UK, undated cutting

- ^ Konrad, Gabor and Melanie, ed (2000), Bikelore: Some History and Heroes of Cycling, On the Wheel, USA, ISBN 1-892495-32-5, p. 134

- ^ Vélo, France, 2000

- ^ a b c d e f g h Busca, Nick (24 May 2021). "Fausto Coppi's War: from Prisoner to Legend". Rouleur. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ Journal, Fellowship of Cycling Old-Timers, UK, vol. 154

- ^ About these years see also "Viva Coppi!", a historical novel written by Filippo Timo

- ^ "Fausto Coppi". Archived from the original on 28 August 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ a b Sudres, Claude, Hors Course, privately published, France

- ^ Een Man Alleen Op Kop, Wieler Revue, Netherlands, undated cutting

- ^ Marco Innocenti, L'Italia del 1948: quando De Gasperi batté Togliatti, Mursia, 1997, p. 133

- ^ "News for January 22, 2002". Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Cycling Weekly, UK, January 2002

- ^ Procycling, UK, March 2002

- ^ Procycling, UK, February 2003

- ^ "Il grande Fausto (TV Movie 1995) - IMDb" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "TEDxMileHigh - Allen Lim - Life with Bikes" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Ciclismo:Piemonte ribattezza Castellania". Euronews (in Italian). Di ANSA. 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Miroir des Sports, France, 1946

- ^ Archive extract from Quando Volava l'Airone, part of a programme called Format, Rai Tre television, 1998

- ^ Cited Nouvel Observateur, France, 19 November 2008

- ^ Cycling, UK, 4 January 1990

- ^ Koomen, Theo (1974), 25 Jaar Doping, De Stem, Netherlands, p144

- ^ Miroir des Sports, France, cited "Fausto Drops a Bomb", Sporting Cyclist, UK, undated cutting

- ^ a b "Fausto Coppi (Italy)". The-Sports.org. Québec, Canada: Info Média Conseil. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ a b c "Palmarès de Fausto Coppi (Ita)" [Awards of Fausto Coppi (Ita)]. Memoire du cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ "Fausto Coppi". Cycling Archives. de Wielersite. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

Bibliography

edit- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour De France, Volume 1: 1903–1964. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.

- Ollivier, Jean-Paul [in French] (1981). Fausto Coppi: The True Story. Translated by Richard Yates. London: Bromley Books. ISBN 978-0-9531395-0-7.

Further reading

edit- Augendre, Jacques (2000). Fausto Coppi. London: Bromley Books. ISBN 978-0-9531729-6-2.

- Buzzati, Dino (1998). The Giro D'Italia: Coppi Versus Bartali at the 1949 Tour of Italy. Boulder, Colorado: VeloPress. ISBN 978-1-884737-51-0.

- Duker, Peter (1982). Coppi. Bognor Regis, UK: New Horizon. ISBN 978-0-86116-945-0.

- Fotheringham, William (2009). Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-224-07447-6.

- Sykes, Herbie (2013). Coppi: Inside the Legend of the Campionissimo. Rouleur Series. London: A & C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-8166-9.

- Trence, Salvatore (c. 1970). Fausto Coppi: "The Campionissimo". Yorkshire, UK: Kennedy Brothers.

External links

edit- Fausto Coppi at Cycling Archives

- Fausto Coppi at ProCyclingStats

- Fausto Coppi at CycleBase

- Fausto Coppi at Cycling Archives (archived)

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | UCI hour record (45.798 km) 7 November 1942 – 29 June 1956 |

Succeeded by |