Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective. He is featured in 53 short stories by English author G. K. Chesterton, published between 1910 and 1936.[1] Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intuition and keen understanding of human nature. Chesterton loosely based him on the Rt Rev. Msgr John O'Connor (1870–1952), a parish priest in Bradford, who was involved in Chesterton's conversion to Catholicism in 1922.[1] Since 2013, the character has been portrayed by Mark Williams in the ongoing BBC television series Father Brown.

| Father Brown | |

|---|---|

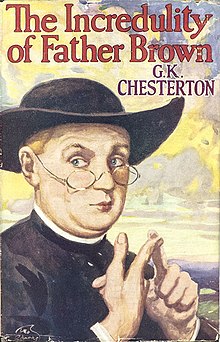

Father Brown by an unidentified artist, The Incredulity of Father Brown, 1926 | |

| First appearance | The Blue Cross |

| Created by | G. K. Chesterton |

| Portrayed by | Walter Connolly Alec Guinness Heinz Rühmann Mervyn Johns Josef Meinrad Kenneth More Barnard Hughes Renato Rascel Andrew Sachs Mark Williams |

| Voiced by | Karl Swenson Leslie French Andrew Sachs |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Priest |

| Nationality | British |

Character

editFather Brown is a short, plain Roman Catholic priest, with shapeless clothes, a large umbrella, and an uncanny insight into human behaviour. His unremarkable, seemingly naïve appearance hides an unexpectedly sharp intelligence and keen powers of observation.[2][3] Brown uses his unimposing demeanor to his advantage when studying criminals, to whom he seems to pose no danger, making him a precursor, in some ways, to Agatha Christie's later detective character Miss Marple.[1] His job as a priest allows him to blend into the background of a crime scene, as others can easily assume he is merely there on spiritual business.[4]

In early stories, Brown is said to be priest for the fictitious small parish of Cobhole in Essex (although it is never named as the actual location of any of them), but he relocates to London and travels to many other places, in England and abroad, during the course of the stories.[4] Much of his background is never disclosed, including his age, family, and domestic arrangements.[4] Even his first name is never made clear; in the story "The Eye of Apollo", he is described as "the Reverend J. Brown" (perhaps in tribute to John O'Connor), while in "The Sign of the Broken Sword", he is apparently named Paul.[5]

Brown's crimesolving method can be described as intuitive and psychological;[2][1] his process is to reconstruct the perpetrator's methods and motives using imaginative empathy, combined with an encyclopaedic criminal knowledge he has picked up from parishioner confessions.[6] While Brown's cases follow the "Fair Play" rules of classic detective fiction,[2] the crime, once revealed, often turns out to be implausible in its practical details.[7] A typical Father Brown story aims not so much to invent a believable criminological procedure as to propose a novel paradox with subtle moral and theological implications.[7][1]

The stories normally contain a rational explanation of who the murderer was and how Brown worked it out. He always emphasises rationality; some stories, such as "The Miracle of Moon Crescent", "The Oracle of the Dog", "The Blast of the Book" and "The Dagger with Wings", poke fun at initially sceptical characters who become convinced of a supernatural explanation for some strange occurrence, but Father Brown easily sees the perfectly ordinary, natural explanation. In fact, he seems to represent an ideal of a devout but considerably educated and "civilised" clergyman. That can be traced to the influence of Roman Catholic thought on Chesterton. Father Brown is characteristically humble and is usually rather quiet, except to say something profound. Although he tends to handle crimes with a steady, realistic approach, he believes in the supernatural as the greatest reason of all.[8]

Background

editWhen he created Father Brown, the English writer G. K. Chesterton was already famous in Britain and America for his philosophical and paradox-laden fiction and nonfiction, including the novel The Man Who Was Thursday, the theological work Orthodoxy, several literary studies, and many brief essays.[9] Father Brown makes his first appearance in the story "The Blue Cross" published in 1910 and continues to appear throughout fifty short stories in five volumes, with two more stories discovered and published posthumously, often assisted in his crime-solving by the reformed criminal M. Hercule Flambeau.

Father Brown also appears in a third story—making a total of fifty-three—that did not appear in the five volumes published in Chesterton's lifetime, "The Donnington Affair", which has a curious history. In the October 1914 issue of an obscure magazine, The Premier, Sir Max Pemberton published the first part of the story, then invited a number of detective story writers, including Chesterton, to use their talents to solve the mystery of the murder described. Chesterton and Father Brown's solution followed in the November issue.[10] The story was first reprinted in the Chesterton Review in 1981,[11] and published in book form in the 1987 collection Thirteen Detectives.[10]

Many of the Father Brown stories were produced for financial reasons and at great speed.[12] Chesterton wrote in 1920 that "I think it only fair to confess that I have myself written some of the worst mystery stories in the world."[13] At the time he wrote this, Chesterton had given up writing Father Brown stories, though he would later return to them; Chesterton wrote 25 Father Brown stories between 1910 and 1914, then another 18 from 1923 to 1927, then 10 more from 1930 to 1936.

Father Brown was a vehicle for conveying Chesterton's worldview and, of all of his characters, is perhaps closest to Chesterton's own point of view, or at least the effect of his point of view. Father Brown solves his crimes through a strict reasoning process more concerned with spiritual and philosophic truths than with scientific details, making him an almost equal counterbalance with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, whose stories Chesterton read.[a]

Compilation books

edit1. The Innocence of Father Brown, 1911

- "The Blue Cross", The Story-Teller, September 1910; first published as "Valentin Follows a Curious Trail", The Saturday Evening Post, 23 July 1910

- "The Secret Garden", The Story-Teller, October 1910. (The Saturday Evening Post, Sep 3, 1910)

- "The Queer Feet", The Story-Teller, November 1910. (The Saturday Evening Post, Oct 1, 1910)

- "The Flying Stars", The Saturday Evening Post, 20 May 1911.

- "The Invisible Man", The Saturday Evening Post, 28 January 1911. (Cassell's Magazine, Feb 1911)

- "The Honour of Israel Gow" (as "The Strange Justice", The Saturday Evening Post, 25 March 1911).

- "The Wrong Shape", The Saturday Evening Post, 10 December 1910.

- "The Sins of Prince Saradine", The Saturday Evening Post, 22 April 1911.

- "The Hammer of God" (as "The Bolt from the Blue", The Saturday Evening Post, 5 November 1910).

- "The Eye of Apollo", The Saturday Evening Post, 25 February 1911.

- "The Sign of the Broken Sword", The Saturday Evening Post, 7 January 1911.

- "The Three Tools of Death", The Saturday Evening Post, 24 June 1911.

2. The Wisdom of Father Brown (1914)

- "The Absence of Mr Glass", McClure's Magazine, November 1912.

- "The Paradise of Thieves", McClure's Magazine, March 1913.

- "The Duel of Dr Hirsch"

- "The Man in the Passage", McClure's Magazine, April 1913.

- "The Mistake of the Machine"

- "The Head of Caesar", The Pall Mall Magazine, June 1913.

- "The Purple Wig", The Pall Mall Magazine, May 1913.

- "The Perishing of the Pendragons", The Pall Mall Magazine, June 1914.

- "The God of the Gongs"

- "The Salad of Colonel Cray"

- "The Strange Crime of John Boulnois", McClure's Magazine, February 1913.

- "The Fairy Tale of Father Brown"

3. The Incredulity of Father Brown (1926)

- "The Resurrection of Father Brown"

- "The Arrow of Heaven" (Nash's Pall Mall Magazine, Jul 1925)

- "The Oracle of the Dog" (Nash's [PMM], Dec 1923)

- "The Miracle of Moon Crescent" (Nash's [PMM], May 1924)

- "The Curse of the Golden Cross" (Nash's [PMM], May 1925)

- "The Dagger with Wings" (Nash's [PMM], Feb 1924)

- "The Doom of the Darnaways" (Nash's [PMM], Jun 1925)

- "The Ghost of Gideon Wise" (Cassell's Magazine, Apr 1926)

4. The Secret of Father Brown (1927)

- "The Secret of Father Brown" (framing story)

- "The Mirror of the Magistrate" (Harper's Magazine, Mar 1925, under the title "The Mirror of Death")

- "The Man with Two Beards"

- "The Song of the Flying Fish"

- "The Actor and the Alibi"

- "The Vanishing of Vaudrey" (Harper's Magazine, Oct 1925)

- "The Worst Crime in the World"

- "The Red Moon of Meru"

- "The Chief Mourner of Marne" (Harper's Magazine, May 1925)

- "The Secret of Flambeau" (framing story)

5. The Scandal of Father Brown (1935)

- "The Scandal of Father Brown", The Story-Teller, November 1933

- "The Quick One", The Saturday Evening Post, 25 November 1933

- "The Blast of the Book/The Five Fugitives" (Liberty Aug 26,1933)

- "The Green Man" (Ladies Home Journal, November 1930)

- "The Pursuit of Mr Blue"

- "The Crime of the Communist" (Collier's Weekly, Jul 14, 1934)

- "The Point of a Pin" (The Saturday Evening Post, Sep 17, 1932)

- "The Insoluble Problem" (The Story-Teller, Mar 1935)

- "The Vampire of the Village" (Strand Magazine, August 1936); included in later editions of The Scandal of Father Brown

6. Uncollected Stories (1914, 1936)

- "The Donnington Affair" (The Premier, November 1914; written with Max Pemberton)

- "The Mask of Midas" (1936)

- Most collections purporting to be The Complete Father Brown reprint the five compilations, but omit one or more of the uncollected stories. Penguin Classics' 2012 edition (ISBN 9780141193854) and Timaios Press (ISBN 9789187611230) are complete ones, including "The Donnington Affair", "The Vampire of the Village" and "The Mask of Midas".

- The Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton, vols. 12 and 13, reprint all the stories including the three not included in the five collections published during Chesterton's lifetime.

Legacy

editAlthough Chesterton himself saw them as ephemeral, the Father Brown stories became his most lastingly popular works, remaining a familiar classic of detective fiction into the twenty-first century.[1][15] T. J. Binyon, in a 1989 survey of fictional detectives, concluded that Father Brown had achieved a fame nearly as great as that of Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot.[6] As Chesterton was already a well-established literary figure before creating Father Brown, the stories' popularity also had a positive impact on detective fiction as a whole, lending the genre further credibility.[9]

Most historians of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction have ranked the Father Brown stories among the best of the genre.[16] Binyon noted that while "the best of the stories are undoubted masterpieces, brilliantly and poetically written", they often hinge on crimes "so fantastic as to render the whole story absurd"; however, "Chesterton's skill as a writer manifests itself precisely in the way in which the moral aspects are concealed", allowing an astute reader to enjoy the stories as parables.[17] Antonio Gramsci, who found the stories "delicious" in their juxtaposition of heightened poetic style and detective-story plotting, argued that Brown was a quintessentially Catholic figure, whose nuanced psychology and moral integrity stand in sharp contrast to "the mechanical thought processes of the Protestants" and make Sherlock Holmes "look like a pretentious little boy".[18]

Kingsley Amis, who called the stories "wonderfully organized puzzles that tell an overlooked truth",[19] argued that they show Chesterton "in top form" as a writer of literary Impressionism, creating "some of the finest, and least regarded descriptive writing of this century":[20]

And it is not just description; it is atmosphere, it anticipates and underlines mood and feeling, usually of the more nervous sort, in terms of sky and water and shadow, the eye that sees and the hand that records acting as one. The result is unmistakable: 'That singular smoky sparkle, at once a confusion and a transparency, which is the strange secret of the Thames, was changing more and more from its grey to its glittering extreme…' Even apart from the alliteration, who else could that be?[20]

P. D. James highlights the stories' "variety of pleasures, including their ingenuity, their wit and intelligence, […] the brilliance of the writing", and especially their insight into "the greatest of all problems, the vagaries of the human heart."[21]

Adaptations

editFilm

edit- Walter Connolly starred as the title character in the 1934 film Father Brown, Detective, based on "The Blue Cross". Connolly would later be cast as another famous fictional detective, Nero Wolfe, in the 1937 film The League of Frightened Men and played Charlie Chan on NBC radio from 1932 to 1938.[22]

- The 1954 film Father Brown (released in the US as The Detective) featured Alec Guinness as Father Brown. Like the 1934 film starring Connolly, it was based on "The Blue Cross". An experience while playing the character reportedly prompted Guinness's own conversion to Roman Catholicism.[23][24]

- Heinz Rühmann played Father Brown in two West German adaptations of Chesterton's stories, Das schwarze Schaf (The Black Sheep, 1960) and Er kann's nicht lassen (He Can't Stop Doing It, 1962) with both music scores written by German composer Martin Böttcher. In these films Brown is an Irish priest. The actor later appeared in Operazione San Pietro (also starring Edward G. Robinson, 1967) as Cardinal Brown, but the film is not based on any Chesterton story.[25]

Radio

edit- A Mutual Broadcasting System radio series, The Adventures of Father Brown (1945), featured Karl Swenson as Father Brown, Bill Griffis as Flambeau and Gretchen Douglas as Nora, the rectory housekeeper.[26]

- In 1974, to celebrate the centenary of Chesterton's birth, five Father Brown stories starring Leslie French as Father Brown and Willie Rushton as Chesterton were broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

- BBC Radio 4 produced a series of Father Brown Stories from 1984 to 1986, starring Andrew Sachs as Father Brown.

- A series of 16 Chesterton stories was produced by the Colonial Radio Theatre in Boston, Massachusetts. Actor J. T. Turner played Father Brown; all scripts were written by British radio dramatist M. J. Elliott. Imagination Theater added this series to their rotation with the broadcast of "The Hammer of God" on 5 May 2013.[27]

Television

edit- "The Quick One" was adapted for the 1964 BBC anthology series Detective, with Mervyn Johns as Father Brown.

- Josef Meinrad played Father Brown in an Austrian TV series (1966–72), which followed Chesterton's plots quite closely.

- In 1974, Kenneth More starred in a 13-episode Father Brown TV series, each episode adapted from one of Chesterton's short stories. The series, produced by Sir Lew Grade for Associated Television, was shown in the United States as part of PBS's Mystery!. They were released on DVD in the UK in 2003 by Acorn Media UK, and in the United States four years later by Acorn Media.

- A US film made for television, Sanctuary of Fear (1979),[28] starred Barnard Hughes as an Americanised, modernised Father Brown in Manhattan, New York City, and Kay Lenz, as Carol Bains. The film was intended as the pilot for a series but critical and audience reaction was unfavourable, largely due to the changes made to the character, and the mundane thriller plot.

- An Italian television miniseries in six episodes, "I racconti di padre Brown" (The Tales of Father Brown) starring Renato Rascel in the title role and Arnoldo Foà as Flambeau was produced and broadcast by the national TV RAI between December 1970 and February 1971 to a wide audience (one episode peaked at 12 million viewers).

- "The Blast of the Book" was adapted into a Russian stop-motion short in 1990.[29]

- A Catholic cable channel, EWTN, produced the Father Brown story "The Honour of Israel Gow" as a 2009 episode of the television series The Theater of the Word.[30]

- A German television series superficially based on the character of Father Brown, Pfarrer Braun, was launched in 2003. Pfarrer Guido Braun, from Bavaria, played by Ottfried Fischer, solves murder cases on the (fictitious) island of Nordersand in the first two episodes. Later, other German landscapes like the Harz, the Rhine, and Meißen in Saxony became sets for the show. Martin Böttcher again wrote the score and he was instructed by the producers to write a title theme hinting at the theme of the movies with Heinz Rühmann. Twenty-two episodes were made, which ran very successfully in Germany on ARD. The 22nd episode, which was aired on 20 March 2014, concluded the series with the death of the protagonist.

- In 2012, the BBC commissioned the 10-episode series Father Brown starring British actor Mark Williams in the title role. It aired on BBC One beginning January 2013, Monday to Friday, over a two-week period in the afternoon. The era and location are moved to the Cotswolds of the early 1950s and used adaptations and original stories. Filming for the series began around the Cotswolds in the summer of 2012.[31] By 2024, 120 episodes had been aired across 11 series.

Audio

edit- Ignatius Press published an audiobook version of The Innocence of Father Brown in 2008. The book is read by actor Kevin O'Brien and features introductions to each story written and read by Dale Ahlquist, president of the American Chesterton Society. The book was a winner of the 2009 Foreword Audio Book Awards.[32]

Appearances and references in other works

editLiterature

editIn Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited, a quote from "The Queer Feet" is an important element of the structure and theme of the book. Waugh's novel quotes Father Brown's line after catching a criminal, hearing his confession, and letting him go: "I caught him, with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world, and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread." In Book Three of Brideshead Revisited, titled "A Twitch Upon the Thread", the quotation acts as a metaphor for the operation of grace in the characters' lives.[33]

Father Brown has occasionally also appeared as a character in works not by Chesterton. In the novel The D Case by Carlo Fruttero and Franco Lucentini, Father Brown joins forces with other famous fictional detectives to solve Charles Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood.[34] The American Chesterton Society published John Peterson's The Return of Father Brown, a further forty-four mysteries solved by a Father Brown living in the United States in his nineties.[35] In the Italian novel Il destino di Padre Brown ("The Destiny of Father Brown") by Paolo Gulisano, the priest detective is elected pope after Pius XI with the pontifical name of Innocent XIV.[36]

Other

edit- Father Brown is one of the detectives on whom Tommy draws inspiration in Agatha Christie's series of short stories featuring Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, published in 1929 under the title Partners in Crime. In "The Man in the Mist", Tommy is dressed as a Catholic priest and his method of investigation refers expressly to those used by Father Brown.

- Ralph McInerny used Father Brown as the spiritual inspiration for his Father Dowling pilot script[37] which launched The Father Dowling Mysteries, a television series that ran from 1987 to 1991 on US television. An anthology of the two detectives' stories, titled Thou Shalt Not Kill: Father Brown, Father Dowling and Other Ecclesiastical Sleuths, was released in 1992.

- Father Brown was highlighted in volume 13 of the Case Closed manga's edition of "Gosho Aoyama's Mystery Library", a section of the graphic novels where the author introduces a different detective (or occasionally, a villain) from mystery literature, television, or other media.

- In the mobile game Fate/Grand Order, in an effort to thwart James Moriarty after his own defeat of Sherlock Holmes, the characters summon up a number of "Phantom Spirits" of fictional detectives that were inspired by or followed after Holmes. The first to appear is a shadowy spirit described simply as "Round-Faced Priest", with the outline and vague features closely resembling the appearance of Father Brown in the Case Closed appearance.

Notes

editFootnotes

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d e f Coren 2003, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Niebuhr 2003, p. 32.

- ^ James 2005, p. xii.

- ^ a b c James 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ Bond 1982, p. xv.

- ^ a b Binyon 1989, p. 64.

- ^ a b Binyon 1989, p. 65.

- ^ LeRoy, Panek (1987), An Introduction to the Detective Story, Bowling Green: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular Press, pp. 105–6.

- ^ a b Bond 1982, p. xvii.

- ^ a b Smith, Marie (1987), Introduction, Thirteen Detectives, by Chesterton, G. K., Smith, Marie (ed.), London: Xanadu, p. 11, ISBN 0-947761-23-3

- ^ Chesterton, G. K. (Winter 1981), "The Donnington Affair", The Chesterton Review, pp. 1–35

- ^ Ker, Ian (2011). G. K. Chesterton: A Biography. Oxford University Press. p. 283. ISBN 9780199601288.

- ^ Chesterton, G. K. (1 July 2011). "Errors about Detective Stories". The Chesterton Review. 37: 15–18. doi:10.5840/chesterton2011371/23.

- ^ G. K. Chesterton's Sherlock Holmes. Baker Street Productions. 2003..

- ^ James 2005, p. xi.

- ^ James 2005, p. xvi.

- ^ Binyon 1989, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Gramsci 2011, p. 354.

- ^ Amis 1974, p. 39.

- ^ a b Amis 1974, p. 38.

- ^ James 2005, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ Cox, Jim (2002), Radio Crime Fighters, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, p. 9, ISBN 0-7864-1390-5.

- ^ "How Father Brown Led Sir Alec Guinness to the Church". Catholic culture. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Tom (7 August 2000). "Sir Alec Guinness obituary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ Hail devil man (29 December 1967). "Operazione San Pietro (1967)". IMDb.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (1999). Radio Programs, 1924–1984: A Catalog of Over 1800 Shows. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0351-9.

- ^ Chesterton, G. K, The Complete Father Brown Stories: Books 1–7, Classics, Starbooks.

- ^ A Walter 1 (23 April 1979). "Sanctuary of Fear (TV Movie 1979)". IMDb.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Проклятая книга (1990)

- ^ "Theater of the Word, Inc. (TV Series 2009– )". IMDb.

- ^ Eames, Tom (22 June 2012). "'Harry Potter' Mark Williams cast in BBC drama 'Father Brown'". Digital Spy. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Books of the year awards". Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Anderson 2020.

- ^ Dickens, Fruttero & Lucentini 1992.

- ^ Peterson 2011.

- ^ Gulisano 2011.

- ^ "Ralph McInerny". The Daily Telegraph. London. 18 February 2010.

Works cited

edit- Amis, Kingsley (1974), Sullivan, John (ed.), "Four Fluent Fellows: An Essay on Chesterton's Fiction", G.K. Chesterton: A Centenary Appraisal, New York: Harper & Row, pp. 28–39

- Anderson, Annesley (24 January 2020), ""A Twitch Upon the Thread": Grace in Brideshead Revisited", Faith & Culture: The Journal of the Augustine Institute

- Binyon, T.J. (1989), Murder Will Out: The Detective in Fiction, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Bond, R. T. (1982), Foreword, The Father Brown Omnibus, by Chesterton, G. K., New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

- Coren, Michael (2003), "Brown, Father", in Herbert, Rosemary (ed.), Whodunit?: A Who's Who in Crime & Mystery Writing, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 24, ISBN 0195157613, OCLC 252700230

- Dickens, Charles; Fruttero, Carlo; Lucentini, Franco (1992), The D. Case, or, The Truth about the Mystery of Edwin Drood, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

- Gramsci, Antonio (2011), Letters from Prison, vol. 1, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 354, ISBN 978-0-231-07553-4

- Gulisano, Paolo (2011), Il destino di Padre Brown, Milan: Sugarco

- James, P. D. (2005), Introduction, Father Brown: The Essential Tales, by Chesterton, G. K., New York: The Modern Library, pp. xi–xvi

- Niebuhr, Gary (2003), Make Mine a Mystery: A Reader's Guide to Mystery and Detective Fiction, Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited

- Peterson, John (2011), The Return of Father Brown, ACS Books, ISBN 978-0-9744495-1-7

Further reading

edit- Gardner, Martin, The Annotated Innocence of Father Brown, Oxford University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-19-217748-6 (Notes by Gardner, on Chesterton's stories).

External links

edit- A collection of Father Brown eBooks at Standard Ebooks

- G. K. Chesterton's Works on the Web

- Father Brown Stories at Faded Page (Canada)

- The Innocence of Father Brown at Project Gutenberg

- The Innocence of Father Brown 1911 First Edition at Open Library

- The Wisdom of Father Brown at Project Gutenberg

- The Wisdom of Father Brown 1914 First Edition at Open Library

- Father Brown public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Review of UK DVD of the 1974 TV series

- Father Brown stories out of copyright in Australia

- Papers of Monsignor John O'Connor the model for Father Brown at the University of St. Michael's College at the University of Toronto